7 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia

Russia’s takeover of Crimea has been accompanied by an ongoing process that is shrinking the space for media and freedom of speech on the peninsula. As the clampdown progressed, a majority of the independent journalists either left the disputed territory or stopped openly criticising Russian policy. At the same time, the number of alternative sources of information declined significantly.

Russian and Crimean authorities have used red tape, paramilitary violence and threats to silence independent voices and media. They have stifled freedom of information and jeopardised journalist safety.

Journalists and media professionals dubbed Crimea “fear peninsula”.

Curtailing broadcast TV

As Russia took over, television stations opposed to the annexation were one of the first targets. In March 2014, Chornomorska, the largest local TV and radio company, and all Ukrainian stations had their analogue broadcasts terminated. This was followed two months later, in June 2014, by the dropping of Ukrainian cable TV channels in some cable networks.

Applying Russia’s extremism law in Crimea

Soon after the annexation, Russia began implementing its overly broad and vague 2002 law, On Countering Extremist Activity, which led to a surge in warnings against the media. In summer 2014, Shevket Kaybullaev, the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Tatar newspaper Avdet , was summoned to the office of public prosecution in Simferopol. Kaybullaev was interrogated because of a complaint against the paper that challenged coverage of the mood of the Tatar community in the run-up to local elections. The complainant accused the paper of “radicalism and extremism”.

Verbal accusations against journalists have also become day-to-day practice. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and prosecutor’s offices demanded the removal of “extremist materials” from media outlets. Crimean Tatar TV channel ATR received two warnings about the “violation of legislation aimed at countering extremist activity”. The station management was reminded that the formation of an anti-Russian public opinion could be considered a violation of the extremist law.

Criminal penalties for “incitement to separatism”

On 9 May 2014, amendments were made to Russia’s Criminal Code. A new article, 280.1, states that “public calls for action aimed at violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation” is punishable by up to five years imprisonment. The words “annexation” and “occupation” are de facto banned in Crimea when referring to recent events.

The amended code has been used to target Crimean journalists. In March 2015, two journalists, the Center for Investigative Journalism’s Anna Andrievska and Natalia Kokorina, had their apartments searched. Kokorina was interrogated for six hours. The FSB opened the criminal case against Andrievska on charges of “incitement to separatism” based on her reporting on individuals providing support for the Crimea volunteer battalion fighting in Donbas, in eastern Ukraine.

Searches and seizure of property

Russian authorities are using searches and property seizure as a way to intimidate and pressurise media companies. In August 2014, the work of Chornomorska TV and Radio Company and the Center for Investigative Journalism were blocked after the seizure of their broadcasting equipment. The broadcaster wasn’t able to retrieve its equipment until five months later.

In September 2014, a search was conducted at the office of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a representative body for the ethnic group. Because it shares the building with the Mejlis, the offices of the Avdet newspaper were also raided. Following the probe, the paper was ordered to vacate its offices within 24 hours.

In January 2015, a search was carried out at the ATR TV channel, which disrupted the station’s broadcasts and prevented newsroom staffers from reporting.

Using paramilitaries to put pressure on journalists

Paramilitary groups have also been used to target journalists. So-called Crimean self-defense groups have been found to have illegally detained, assaulted and tortured journalists, as well as confiscations of and damage to property. From 15 to 19 May, 2014, ten cases of journalists’ rights violations were recorded and documented by the Crimea Field Mission on Human Rights. The situation has been worsened by the fact that to date not all the documented attacks on journalists by self-defense group members have been investigated by Crimean authorities. This has created an atmosphere of fear and impunity.

Problems with registration and re-registration of Crimean media

After the Russian annexation, Crimean authorities demanded that all active media outlets re-register according to Russian legislation. As a result, mass media that was considered disloyal — including News Agency QHA and TV Channel ATR, among others — did not receive legal permission to continue their work on the peninsula. In February 2015, all Crimean independent radio companies were silenced after losing their frequencies during a bidding process that was carried out opaquely. Beginning on 1 April 2015, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Communications (Roskomnadzor) stopped recognising Crimean media outlets with Ukrainian registrations, making their work in the annexed territory illegal.

Making media accreditation more difficult

New rules for accreditation in Crimea make it possible to selectively restrict media access to the authorities. The State Council of the Republic of Crimea issued new regulations that make “biased coverage” one of the reasons journalists could lose accreditation. Kerch City Council, for instance, prohibits journalists without accreditation from even entering the city hall.

Blocking access to the online media

In October 2015, media freedom in Crimea came under renewed pressure when websites were blocked. Roskomnadzor carried out a request by the general prosecutor to restrict access to the Center for Investigative Journalism and Events Crimea websites in Crimea and Russia. Roskomnadzor said that the information on the sites “contains calls for riots, realisation of extremist activity and/or participation in mass (public) events held in violation of the established order”.

These internet media outlets became the first Crimean mass media whose content are officially blocked on the territory of Crimean peninsula.

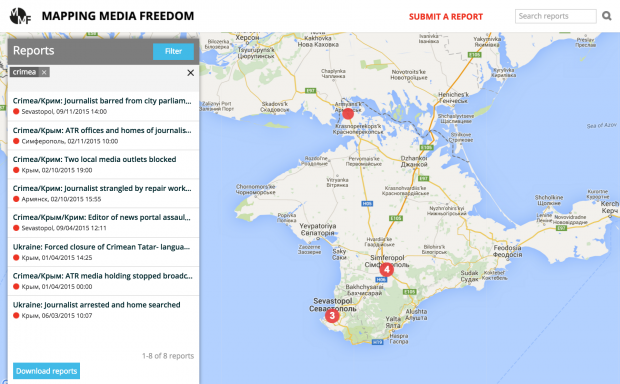

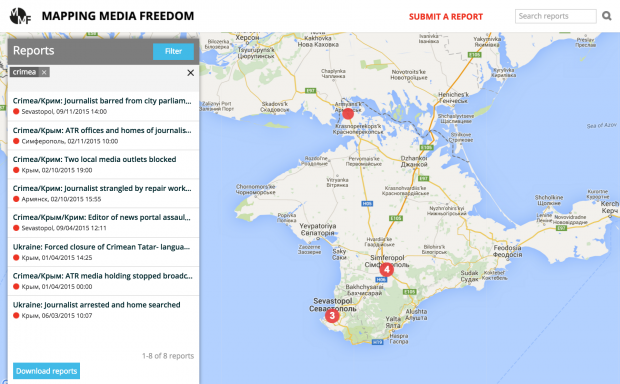

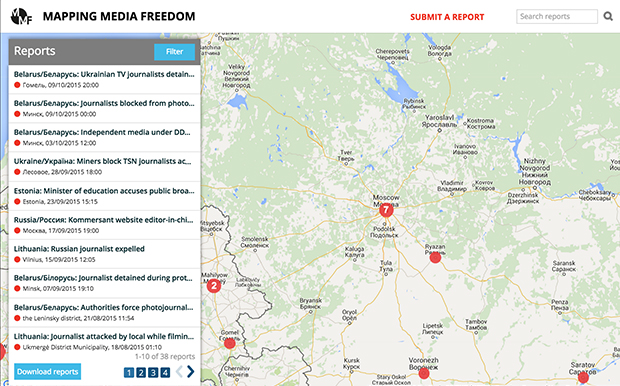

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

4 Dec 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Campaigns, mobile

Khadija Ismayilova

On the eve of the anniversary of the arrest of journalist Khadija Ismayilova, members of the Sport for Rights coalition and the Civic Solidarity Platform underscore the unprecedented nature of the repression that has taken place in Azerbaijan in the year that has passed. The groups reiterate their call for the immediate and unconditional release of Ismayilova and Azerbaijan’s other political prisoners, and for the international community to take steps to hold the Azerbaijani government accountable for its human rights obligations as matter of urgent priority.

“Ismayilova’s arrest a year ago signalled an escalation of repression in Azerbaijan”, noted Karin Deutsch Karlekar, Director of Free Expression Programs at PEN American Center. “Independent voices are being silenced at an unprecedented rate, and we urge the authorities to cease the legal and extra-legal harassment of journalists and media outlets immediately”.

On 5 December 2014, prominent investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested on charges of inciting a local man, Tural Mustafayev, to attempt suicide. Two months later, authorities slammed her with additional politicised charges of embezzlement, illegal business, tax evasion, and abuse of power. After eight months in pre-trial detention, Ismayilova’s trial started on 7 August at the Baku Court of Grave Crimes.

Ismayilova referred to the proceedings as an “express trial”, and observers noted it was rife with due process violations, with the judges rarely granting any motions made by the defence. During the trial, Mustafayev publicly told the court that prosecutors forced him to make a statement against Ismayilova, and withdrew his accusations. Additionally, Ismayilova’s lawyer told the court that her employer did not report any funds missing, that she was not authorised to hire or dismiss other journalists, and that she was not engaged in any commercial enterprise.

On 1 September, the court convicted Ismayilova of the charges of embezzlement, illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion, and abuse of office, and sentenced her to 7.5 years’ imprisonment. She was acquitted of the charge of inciting Mustafayev to attempt suicide. On 25 November, the Baku Court of Appeals upheld this conviction, and Ismayilova was transferred to Prison Number 4 on 27 November.

Sport for Rights considers the charges against Ismayilova to be politically motivated and connected to her work as an investigative journalist, particularly her exposure of corruption among the ruling elite. Sport for Rights believes that in jailing Ismayilova, the Azerbaijani authorities sought to silence her critical voice before the country faced increased international media attention during the inaugural European Games, which took place in Baku in June. For this reason, Sport for Rights has referred to Ismayilova as a “Prisoner of the Games”.

“Ismayilova’s imprisonment is emblematic of the Azerbaijani authorities’ repression of independent journalists and human rights defenders”, said Melody Patry, Senior Advocacy Officer at Index on Censorship. “Every day Ismayilova and the other political prisoners spend in jail is another reminder to the world that the Azerbaijani government fails to respect and protect the democratic principles and fundamental rights it has committed to upholding”.

Ismayilova is one of dozens of political prisoners in Azerbaijan. Other prominent cases include journalists Nijat Aliyev, Araz Guliyev, Parviz Hashimli, Seymur Hezi, Hilal Mammadov, Rauf Mirkadirov, and Tofig Yagublu; bloggers Abdul Abilov, Faraj Karimli, Omar Mammadov, Rashad Ramazanov, and Ilkin Rustamzade; human rights defenders Intigam Aliyev, Rasul Jafarov, Taleh Khasmammadov, Anar Mammadli, Arif Yunus, and Leyla Yunus; NIDA civic movement activists Rashadat Akundov, Mammad Azizov, and Rashad Hasanov; opposition activist Yadigar Sadikhov; and opposition REAL movement chairman Ilgar Mammadov.

Besides politically motivated arrests and imprisonment, the Azerbaijani authorities continue to employ a wide range of tactics as part of an aggressive crackdown to silence the country’s few remaining critical voices. Independent online television station Meydan TV has been a particular target, with its staff and their relatives threatened, detained, and otherwise pressured in connection with Meydan TV’s critical news coverage of Azerbaijan. Other independent NGOs and media including the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety and its online television project Obyektiv TV, as well as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Baku office, have also been aggressively targeted over the past year.

In addition to the post-European Games crackdown, the Azerbaijani authorities also worked to silence criticism ahead of the 1 November parliamentary elections. For the first time, the elections took place with almost no credible international observers, and with the majority of the traditional opposition boycotting. Independent domestic observers reported widespread fraud, such as carousel voting and irregularities in the vote counting and tabulation process. Now, in the run-up to the Formula One European Grand Prix, which will take place in Baku in June 2016, the crackdown shows no signs of relenting.

These issues and more are detailed in a new Sport for Rights report, No Holds Barred: Azerbaijan’s Human Rights Crackdown in Aliyev’s Third Term, which also contains specific recommendations to the Azerbaijani authorities and the international community on urgent measures needed to improve the dire human rights situation in the country. Sport for Rights and the Civic Solidarity Platform particularly urge the international community to sustain focus on Azerbaijan over the coming months, when critical voices will need concrete support more than ever before.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law Enforcement

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights (Russia)

Civil Rights Defenders

Committee to Protect Journalists

Crude Accountability

Freedom Now

Front Line Defenders

Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association

Golos Svobody Public Foundation (Kyrgyzstan)

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Index on Censorship

Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), within the framework of the

Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

International Partnership for Human Rights

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Kharkiv Regional Foundation – Public Alternative (Ukraine)

Kosova Rehabilitation Centre for Torture Victims

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN American Center

People In Need

Platform

Promo-LEX (Moldova)

Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

Reporters Without Borders

Sova Center for Information and Analysis (Russia)

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the

Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

3 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Propaganda, counterpropaganda and information wars are all terms that, unfortunately, have become part of our daily discourse.

Propaganda, counterpropaganda and information wars are all terms that, unfortunately, have become part of our daily discourse.

As the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, I have raised the issue of propaganda emanating from the conflict in and around Ukraine. I have called propaganda an ugly scar on the face of modern journalism and called on governments to get out of the news business.

Tackling propaganda is not a new concept to the participating states of the OSCE. It goes back to the beginning of this organization. At the time of the Helsinki Final Act, the participating states committed themselves to promote “a climate of confidence and respect among peoples consonant with their duty to refrain from propaganda for wars of aggression” against other participating states.

Those promises were broken for the first time before and during the war in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Dangerous stereotypes that dominated state media since the beginning of the crisis significantly contributed to the development of an intolerant atmosphere and influenced people’s beliefs and increased feelings of national and religious differences.

Creating an environment of fear and general anxiety, with constant labelling of enemies was now expanded to nationalities. Ethnic intolerance, built by cleverly devised propaganda in the media, resulted in general support for a brutal war. Many studies and much research about the role of media in the former-Yugoslav conflict indicated that media, while serving the regime, produced war and hatred.

Fast forward to 2015. The media landscape has changed almost completely, but journalism still suffers from propaganda and its wicked elements. In the 21st century, where new technologies are bringing information – and journalism – to readers in new ways and faster than ever before, propaganda is alive and doing very well.

It is apparent that some media are in dire need of self-examination. There is a need to cleanse journalism of fear, propaganda and routine frustration. In the absence of critical journalism, democracy suffers and deliberate misinformation becomes the standard.

In the past 12 months my office has been heavily engaged in a campaign on several fronts to attack the root causes of propaganda and its all-too-likely consequences: ignorance, hate and hostility. My team has spent considerable time and resources working with Russian and Ukrainian journalists in confidence-building measures designed to bridge the gap between them. We have instituted training for young journalists from the two states on such topics as ethics in journalism, conflict reporting and propaganda.

The latest element in our campaign against propaganda was just published: Propaganda and Freedom of the Media offers an in-depth look at at the legal and historical basis against propaganda.

The report recommends that:

- Media pluralism must be enforced as an effective response that creates and strengthens a culture of peace, tolerance and mutual respect.

- Governments and political leaders should refrain from funding and using propaganda.

- Public service media with strong professional standards should be strongly supported in their independent, sustainable and accessible activity.

- Propaganda should be generally uncovered and condemned by governments, civil society and international organizations as inappropriate speech.

- The independence of the judiciary and media regulators should be guaranteed in law and in policy.

- The root causes of propaganda for war and hatred should be dealt with a broad set of policy measures.

- National and international human rights and media freedom mechanisms should be enabled to foster social dialogue in a vibrant civil society and also address complaints about incidents of hateful propaganda.

- Strengthening educational programmes on media literacy and internet literacy may dampen the flames that fire propagandists.

- Media self-regulation, where it is effective, remains the most appropriate way to address professional issues.

Propaganda does a disservice to all credible, ethical journalists who have fought for and, in some cases, given their lives to produce real, honest journalism. In sum, propaganda for war and hatred is effective only in environments where governments control media and silently support hate speech. A resilient, free media system is an antidote to hatred.

My hope is that the report Propaganda and Freedom of the Media will assist OSCE participating States, policymakers, academia and media professionals throughout the OSCE region and beyond.

13 Nov 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia

When the Tomsk-based station TV-2 ceased broadcasting earlier this year, Siberia lost one of its few independent stations. The channel was about as free as media can be in Russia: it wasn’t funded by a state or municipal budget.

The road to its closure began in April 2014 when an antenna malfunctioned. It took 45 days to get back on the air. When it resumed transmission in June 2014, Roskomnadzor – the Russian authority that oversees media and communications – revoked the station’s right to broadcast. A previous licence extension though 2025 had been issued as a result of a “computer error”, the agency explained.

On 1 January 2015, the station stopped broadcasting over the airwaves. In February 2015, it ceased to be an internet and cable station as well.

In Russia, independent media will not likely be shuttered because of critical coverage of the state. It will have its licence revoked because glitch or be silenced through a broken feeder or some other mundane technicality.

Early in the Putin era, Moscow-based national networks could be caught in a “dispute of economic entities” to silence narratives that were contrary to the government’s line. Media takeovers by businesses aligned with the government of President Vladimir Putin drew the world’s attention and criticism. But in Russia’s hinterland, the decline of media freedom was more precipitous.

Despite a professed respect for the rule of law in Russia, regional media outlets are caught between harsh oversight by local authorities and a lack of independent sources of funding. At the same time, business interests and regional governments are often more closely affiliated than in larger cities. Nepotism and conflicts of interest are rife while courts are hamstrung by corruption.

Journalists are often victims. According to Glasnost Defense Foundation, 150 journalists were killed in Russia during last 15 years. Authorities ignored crimes against journalists and tightened the screws by criminalising slander, which spurred lawsuits that helped destroy independent-minded free media.

When journalists do uncover corruption, regional authorities act to silence them by meting out punishment for “crimes” that the individual has committed. This is highlighted by the recent case of Natalya Balyakina, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Chaikovskie Vedomosti. A well-known journalist who investigated allegations of misconduct by local officials involving the area’s municipal housing and human rights violations, Balyakina was awarded the 2007 Andrey Sakharov prize for journalism.

On 22 October 2015, the Chaikovski city court sentenced her to three years of incarceration and 761,000 rubles ($11,818) in fines and damages. Balyakina was convicted of a crime that she allegedly committed five years ago, when she was director of the regional City Managing Company. Her former company has accused her of misappropriation and embezzlement.

Whether or not the allegations against Balyakina are true, Chaikovski regional authorities benefit by having yet another investigative journalist silenced.

Regional media must also contend with a dearth of independent funding. As a result, these outlets are often forced to sign affiliation agreements with local administrators. These deals come with restrictions on how the organisations can cover regional government activities.

Journalists reporting for these affiliated outlets say they receive direct instructions on what they can write about. The editor-in-chief of one newspaper was prohibited from publishing any issues regarding healthcare because there was nothing positive to cover. Regional events that are reported by national media — disasters or human rights violations — are not covered by local outlets due to positive news restrictions.

But even the cowed national media is under continued assault. The Russian Duma is considering a bill that will allow Roskomnadzor to compel media organisations to disclose foreign funding or material support. So software provided by Microsoft could cause a regional outlet to be labelled as a “foreign agent” on the same model of the NGO law that was passed in 2012.

Long under pressure from official censorship and self-censorship, journalists’ sources are now being constrained by punitive laws that have enlarged state secrets and toughened punishments. In June 2015, Putin signed a law that classified Ministry of Defence casualties during peacetime. The result is that journalists are now forbidden from reporting on the number of Russian soldiers killed in action in Ukraine or Syria.

The Federal Security Service (FSB) is also lobbying members of the Duma to pass a draft law that restricts freedom of information around real estate transactions. Some observers say that this will hinder work to uncover corruption committed by Russian officials carried out by bloggers and journalists.

The media in Russia became one of the core targets during the strengthening political powers in last decades, but the regional journalists are put in an especially weak position.

This is one of a series articles on Russia published today by Index on Censorship. To read about the chilling effect blasphemy laws have had on free speech in Russia, click here.

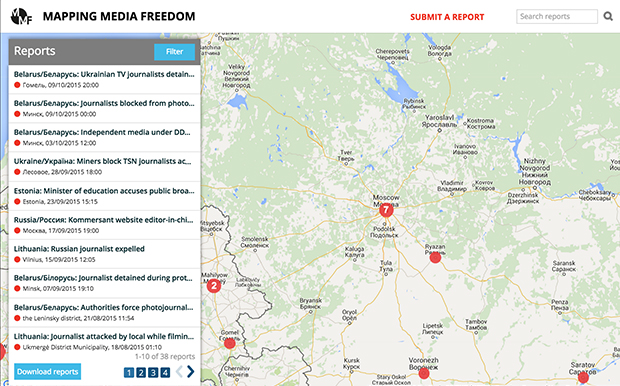

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 13 November 2015