29 Mar 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The undersigned international press freedom groups call on Turkish authorities to immediately release the 12 printworkers and staff arrested on 28 March at the premises and print works of the newspaper Özgürlükçü Demokrasi and the further 15 staff taken into custody after home raids on the morning of 29 March 2018. Authorities must also restore control over the paper and its premises to the rightful owners.

The below-named organizations also denounce the fact that lawyers acting for those arrested have been denied contact with prosecutors or access to any written documentation in relation to the raids.

Two officials purporting to be from the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) are in place at the print works and premises of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi, a pro-Kurdish daily, and claim to be holding the sites until they receive further instructions. For its part, the TMSF, now part of the Ministry of Finance’s Directorate of National Estates and formerly an independent banking watchdog under the auspices of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, has denied having received instructions to seize the newspaper’s assets.

According to lawyers acting for the detained printworkers and Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s principal signatory İhsan Yaşar and Kasım Zengin the owner of Gün Printing Advertising Film and Publishing Inc, where the newspaper is printed, a press crimes investigation into the paper was opened on February 7. This was followed by a separate counter-terrorism investigation that began on March 23. It is believed that both investigations, of which no written notification has been made to the paper, are in relation to Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s coverage of Turkey’s incursion into Afrin, northern Syria.

As the sole remaining Kurdish daily newspaper in Istanbul, Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is vital in maintaining the extremely fragile access to information that is not controlled by the state. Following the closure of other pro-Kurdish newspapers and television stations such as Azadiya Welat, IMC TV and Hayatın Sesi in 2016, Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is one of the last sources of pro-Kurdish daily printed news in Turkey.

“The Turkish authorities must halt their sustained repression of Kurdish culture and language. We are highly alarmed by the onslaught on Kurdish and pro-Kurdish media outlets and journalists that has intensified dramatically since the crackdown on freedom of expression since the attempted coup of July 2016, and now reached a new low point with this takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi,” said Carles Torner, Executive Director of Pen International.

We, the signatories of this statement, strongly condemn the takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi, which has taken place without any legal justification or documentation. We reject the denial of information and prosecutorial access to lawyers acting for Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s arrested staff members.

“The government’s takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is extremely concerning,” said Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship, “We urge European and other governments to condemn the obliteration of free media in Turkey.”

We call for the release of the arrested staff members and printworkers and official confirmation from the TMSF of the legal status of the alleged acquisition of Engin Publishing Print Inc. — and the Gün Printing Advertising Film and Publishing Inc.

Katie Morris, Head of Europe and Central Asia Programme at Article 19 said: “The takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi restricts the space for freedom of expression even further in Turkey and curtails the right of the public to access information on issues of public interest, particularly in relation to the on-going conflict in the South East of the country. We call for the authorities to cease harassing this newspaper and restore much-needed media freedom in Turkey.”

The takeover of one of the last remaining opposition newspapers follows the acquisition last week of Turkey’s largest media organization and newspaper distributor, Doğan Group, by Turkish conglomerate Demirören, whose media outlets are known for taking a pro-government stance. In the week prior to the purchase, an internet streaming bill was passed granting the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) sweeping powers to monitor, license and block online streaming channels and news providers.

“This latest act against freedom press confirms that Erdogan wants to repress any free voice in Turkey. A firm position in Europe is needed to make pressure the Turkish government to restore the rule of law as soon as possible with the cessation of the state of emergency,” said Antonella Napoli member of Articolo 21 and coordinator of Free Turkey Media in Italy.

International Press Institute (IPI)’s Turkey Advocacy Coordinator Caroline Stockford said, “IPI strongly condemns yesterday’s raid and the government’s tactic of shutting down Özgürlükçü Demokrasi in an apparently illegal manner in order to silence dissenting voices in the run-up to the presidential elections. Despite the opportunity presenting itself at this week’s Varna summit, Europe failed again to strongly condemn Turkey’s repression of free media and free speech.”

The peoples of Turkey have a right to access informative opposition reporting in order to form a balanced opinion, especially in the lead up to an election. We call on Turkey to respect the human right to freedom of expression and to refrain from its practice of stifling all opposition media and to release the Özgürlükçü Demokrasi workers from detention.

We, the undersigned, call on European newspapers and governments to make clear statements to Turkey that access to balanced, critical reporting is essential to democracy and that the freedom of the press must be respected and maintained.

International Press Institute (IPI)

Pen International

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF)

Article 19

Norwegian Pen

Index on Censorship

English Pen

Articolo 21

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Pen Belgium/Flanders

Wales Pen Cymru

Pen Germany

Pen Club Français

Pen Suisse Romand[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522334755757-294591af-d9eb-2″ taxonomies=”1743″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Mar 2018 | Event Reports, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

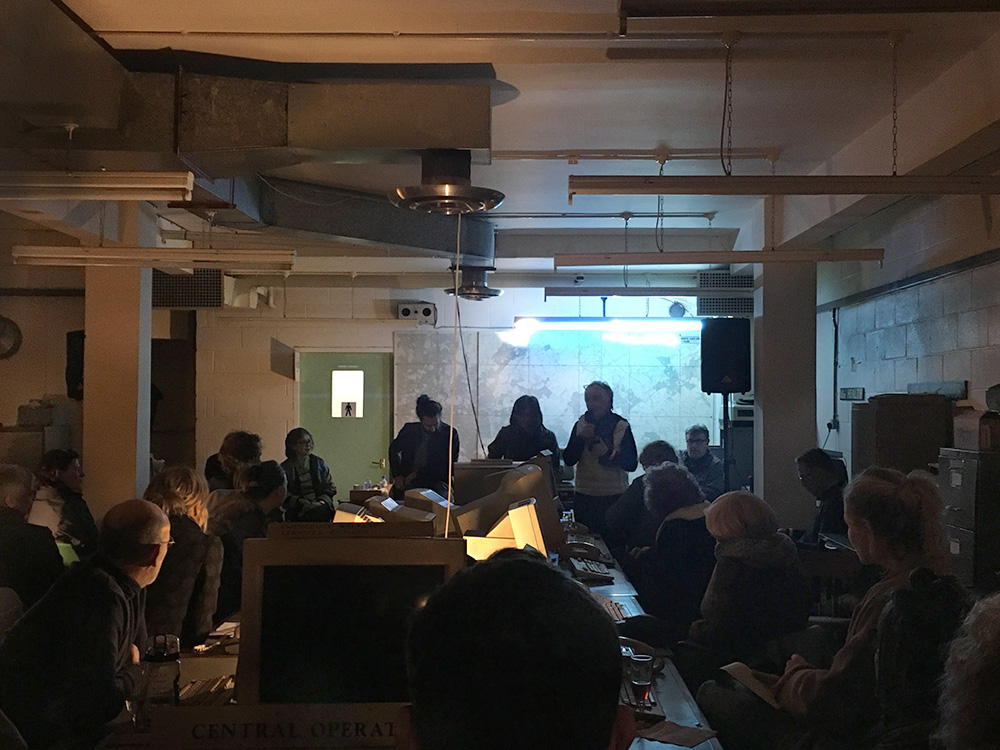

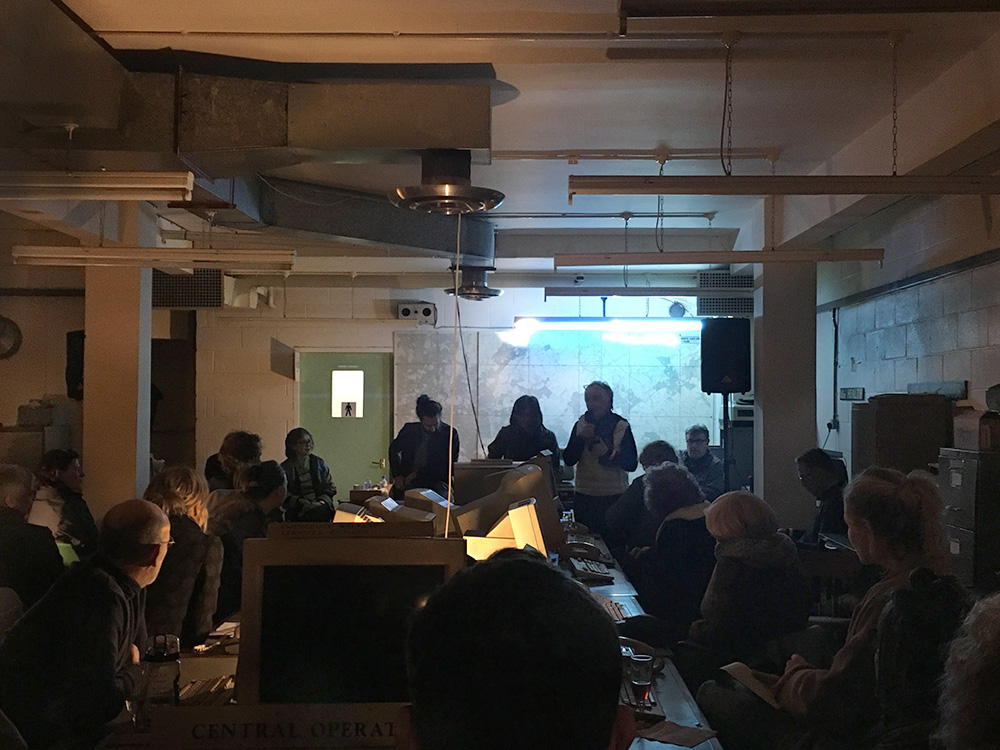

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Mar 2018

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521806157541{margin-top: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_web-cover.jpg?id=98589) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: contain !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1521805928920{margin-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

The case of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, who had for years worked to shine a light on corruption among politicians, businessmen and criminals in Malta, highlights the dire need for a free press. Between 2016 and 2017 Caruana Galizia linked the Maltese political elite to the Panama Papers, including the financial affairs of the prime minister, his wife and the leader of the country’s opposition party.

For her work, she paid with her life when a bomb exploded under her car on 16 October. She was not the only journalist to be murdered in Europe in 2017, nor were violations of media freedom confined to any one region.

Mapping Media Freedom has been recording threats to press freedom since 2014, highlighting the need for protection for journalists. The project monitors the media environment in 42 European and neighbouring countries. In 2017 1,089 reports of limitations to press freedom were verified by a network of correspondents, partners and other sources based in Europe, with a majority of violations coming from official or governmental bodies.

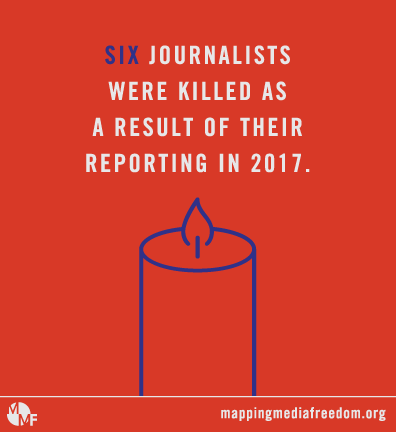

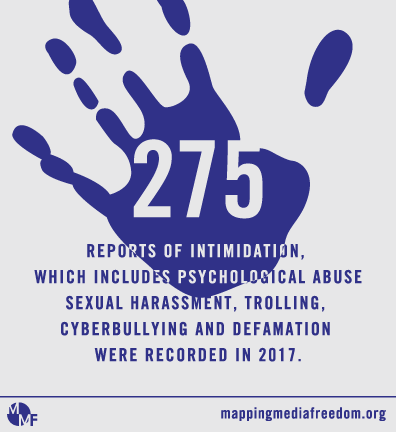

Six journalists were killed during 2017; 178 reports of assault or injury were made; 220 media workers were detained or arrested; 193 reports included criminal charges and lawsuits; there were 367 reports of intimidation, which includes psychological abuse, sexual harassment, trolling/cyberbullying and defamation; in 113 incidents media professionals had their property vandalised or confiscated; there were 178 instances of journalists or sources being blocked; and journalists’ work was altered or censored 68 times.

“While the number of incidents reported to Mapping Media Freedom decreased between 2016 and 2017, this should not be taken as an indication that the work environment for journalists has improved in the countries monitored by the platform,” Hannah Machlin, project manager of Mapping Media Freedom, said. “Media professionals still work under threat of death, assault, prison and harassment, while the law is being abused as a means to silence those who seek to tell the truth.”

ABOUT MAPPING MEDIA FREEDOM

Each report is fact-checked with local sources before becoming publicly available on Mapping Media Freedom. The number of reports per country relates to the number of incidents reported to the map. The data should not be taken as representing absolute numbers. For example, the number of reported incidents of censorship appears low given the number of other types of incidents reported on the map. This could be due to an increase in acts of intimidation and pressure that deter media workers from reporting such cases.

The platform – a joint undertaking with the European Federation of Journalists partially funded by the European Commission – covers 42 countries, including all EU member states, plus Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Turkey, along with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (added in April 2015), and Azerbaijan (added in February 2016). The database uses Ushahidi, an open source software to map and categorise incidents.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes”][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Deaths” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Q1: In Russia on 9 March, two unknown individuals approached Nikolai Andrushchenko, an investigative journalist for the weekly newspaper Novyi Petersburg, near his home in St. Petersburg and demanded that he surrender documents and materials from his ongoing investigation into abuses of power by police officers. After the journalist refused, he was physically assaulted by the assailants, who were not apprehended. Andrushchenko refused to file a complaint with the police. A second assault took place a few days later, after which he was found unconscious near his apartment. The journalist never regained consciousness and, following brain surgery, died in hospital as a result of his injuries on 19 April.

On 16 March, in Ulan-Ude, Russia, Yevgeny Khamaganov, the editor-in-chief of Asia-Russia Daily and The Site of the Buryat People died in unexplained circumstances. The cause of death is unclear and no official response has been made. According to local media, Khamaganov was taken to hospital on 10 March because of his diabetes, fell into a coma and died several days later. Some reports cited speculation that he was instead hospitalised after being beaten by unknown assailants. Khamaganov was known for articles critical of the Russian federal government’s policies.

Q2: In Minusinsk, Russia, journalist Dmitri Popkov, editor-in-chief and founder of local newspaper Ton-M, was shot five times and killed on 24 May. His body was found in a sauna in his backyard. Prior to his death, Popkov had told RFE/RL that his newspaper became “an obstacle” for local officials who are now “threatening and intimidating journalists”.

Q3: On 10 August Swedish freelance journalist Kim Wall boarded an experimental submarine in Copenhagen, Denmark, to profile the vessel’s Danish inventor. The following morning, the submarine sank under suspicious circumstances. Peter Madsen, the inventor, told police he had set Wall ashore before the incident. However, between August and October, Wall’s dismembered remains were found washed ashore. Madsen has been charged with the journalist’s murder and with sexual assault.

On 22 September Syrian journalists Orouba Barakat and her daughter Halla Barakat were found dead in their apartment in Istanbul, Turkey. The exact date of the murders is unknown. Orouba Barakat, a journalist, filmmaker and activist, was outspokenly critical of the Syrian regime. Her daughter was a reporter for Alekhbarya TV, news editor for the Orient and a former editor at Turkish state channel TRT World. The pair had received threats from groups associated with the Syrian government. Police reports said they were strangled and then stabbed. The murders are still being investigated by police.

Q4: Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed when the car she was driving exploded in Bidnija, near Mosta. Caruana Galizia had filed a police report 15 days earlier saying she was being threatened. The journalist had conducted a series of high-profile corruption investigations in Malta and was being sued in relation to her work.

One additional media worker was killed in 2017. On 29 April Saeed Karimian, an Iranian television executive, was shot and killed along with his partner in Istanbul, Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Physical assaults and injury” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

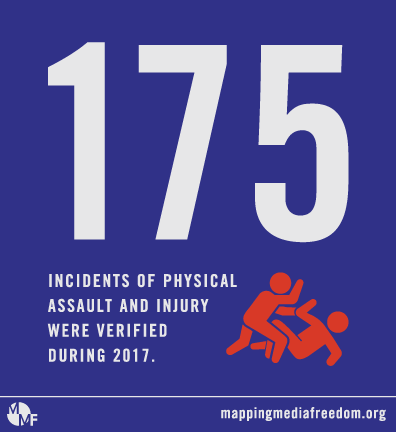

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

On 14 September Taras Khalyava, a local YouTube blogger, was assaulted by three unidentified people near his apartment in Dobropillye, Ukraine. The assailants knocked him to the ground, kicked him and beat him on the head with a steel rod. “I survived because I was wearing a bicycle helmet,” Khalyava told Novosti Donbassa. The blogger has said the attack was related to his work.

On 10 October, Drago Miljus, a Croatian journalist for the news website Index.hr, was pushed by a police officer, who then took his mobile phone and threw it into the sea. Another officer hit the journalist on the head, knocking him to the ground. The incident happened at a beach in Split, where Miljus was covering a story about a man who claimed to have a bomb.

On 23 October, a man broke into Echo Moskvy’s office in the centre of Moscow, Russia, and stabbed programme host Tatiana Felgengauer, who is also one of the editor-in-chief’s deputies, several times in the neck. Felgengauer was hospitalised in a critical condition and underwent several operations. The attacker was sent for psychiatric evaluation.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Arrests/Detainments” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court.

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Georgia, where he had lived in self-imposed exile for three years, and taken to Azerbaijan. While in prison, he suffered serious health problems and lost a significant amount of weight. In January 2018 he was sentenced to six years in prison by an Azerbaijani court.

Mapping Media Freedom verified the arrest or detainment of 65 journalists in Russia throughout 2017. The majority of these took place during anti-corruption protests throughout the country organised by opposition figure Alexei Navalny in March and June.

By the close of 2017, 151 journalists were in prison in Turkey, making the country the largest jailer of journalists in the world. On 20 October police took five journalists working for the Kurdish Jin News and Mesopotamia agencies into custody: Jin News editor Sibel Yükler; Jin News reporters Duygu Erol and Habibe Eren; and Mezopotamya Agency reporters Diren Yurtsever and Selman Güzelyüz. Both agencies were launched in late September by staff from organisations shut down during Turkey’s state of emergency.

While only five media workers were arrested or detained in 2017 in the United Kingdom, one case stands out. On 7 December two Kurdish women and two 17-year-old boys were arrested at dawn by armed police in Alexandra Palace and in Crouch End, London. They were questioned about the sale and distribution of the Kurdish-language Yeni Ozgur Politika. All four were arrested on suspicion of funding terrorism, money laundering and fraud.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Criminal charges/civil lawsuits” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest.

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. In Italy, lawsuits demanding millions of euros in damages were filed throughout the year. In March Claudio Riva, former owner of the steelworks company Ilva, sued newspaper Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno for €2.2 million in damages, for publishing an article about pollution allegedly linked to the company’s operations in Taranto. Riva’s lawyers asked for €550,000 in compensation for each of the four damaged parties: Riva Forni Elettrici SPA, Claudio Riva, Fabio Arturo Riva and Nicola Riva. In October Il Locale News was sued for €1 million by Giancarlo Guarrera, an engineer and director of Airgest, the company that manages Trapani airport in Sicily. On 8 November 2016 Il Locale News featured an article on financial issues at Airgest.

In Spain, wealthy businessman Alvaro de Marichalar filed legal action against freelance journalist Sabina Urraca in March, demanding she pay €30,000 in damages for an article she wrote after accompanying him on a trip. In July Hermann Tertsch, a columnist for daily newspaper ABC, was ordered by a court in Zamora to pay €12,000 to Javier Iglesias for “unlawfully offending the honour” of his father Manuel. Javier Iglesias is the father of Pablo Iglesias, the leader of the left-wing Podemos party, the third largest party in the Spanish parliament.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Legal measures” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In the United Kingdom, the offshore company Appleby, which was at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal, launched breach of confidence proceedings against the Guardian and the BBC on 18 December, in an attempt to force them to disclose the documents used in the investigation. Appleby said the documents were stolen in a cyberattack and there was no public interest in the revealing of their contents.

In February the UK government proposed extending jail time for journalists who have obtained leaked official documents to up to 14 years. The major overhaul of the Official Secrets Act – to be replaced by an updated Espionage Act – would give courts the power to increase jail terms against journalists receiving such material. Should the law get approval, documents containing “sensitive information” about the economy could fall foul of national security laws for the first time. Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive of Index on Censorship, said: “It is unthinkable that whistleblowers and those to whom they reveal their information should face jail for leaking and receiving information that is in the public interest.”

In November, after the US added several media outlets funded by the Russian state on a list of foreign agents, Russia adopted a new restrictive law against foreign media that allows such journalists and organisations to be recognised as foreign agents, which makes them subject to numerous additional checks and obliges them to mark their content as being produced by a foreign agent.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Job loss” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

In Poland, Michał Fabisiak, a journalist for the public media outlet Polskie Radio, was fired for refusing to reveal the source of information for an article about an alleged internal survey in the Law and Justice (PiS) party, measuring support for potential PiS candidates in municipal elections in 2018.

Eleven days later, Barbara Burdzy, a Polish journalist for the public media outlet TVP Info, was dismissed after she published an article stating that the intelligence service, under the minister of defence Antoni Macierewicz, lied when claiming that deputy minister Jacek Kotas was not involved in property restoration in Warsaw.

On 14 December a documentary critical of Togo’s president was removed from the website of the French cable television channel Canal Plus and two employees of the channel were subsequently dismissed. Faure Gnassingbé, the president of Togo, is a friend of Vincent Bolloré, French businessman and chairman of Canal Plus’ parent company Vivendi. The documentary, entitled Let Go of the Throne, focused on ongoing protests against the country’s president. In November it was aired on Canal Afrique, a decision attributed to an employee who was later fired. François Deplanck, head of channels and content at Canal Plus International was also dismissed.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Intimidation” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

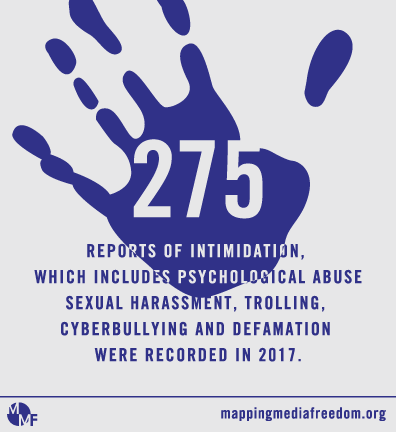

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the BBC’s political editor Laura Kuenssberg was assigned a security detail at the Labour party conference in late September following online threats and abuse. The journalist attracted anger from some Labour supporters for her coverage of the 2016 Labour leadership race and the party’s poor performance in local elections, while a petition for her to be fired received 35,000 signatures.

Kuenssberg — the first woman to lead political coverage at the public broadcaster — also reported that she had bolstered her security during the general election in June 2017 after receiving threats over her coverage of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Attacks to property” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service. Her brakes had been cut and her anti-lock braking system was damaged. Zavialova called the police but, according to the journalist, they did not properly investigate the scene, failing to take fingerprints or full details of the damage.

Supporters of the Italian far-right party Forza Nuova attacked the offices of the left-wing newspaper La Repubblica in Rome on 6 December. The party declared “war” on L’Espresso Group, the newspaper’s publisher, through a Facebook post. During the protest, Forza Nuova supporters threw flares at La Repubblica’s office while carrying a banner reading “Boycott L’Espresso and La Repubblica”. Members of the group read a statement denouncing journalists employed there.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Blocked access” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

Throughout Europe, journalists were blocked from attending events by political parties, including the Labour Party’s annual conference in Brighton, United Kingdom, in September. Sussex police refused to grant Huck Magazine news editor Michael Segalov the security clearance he needed to attend. The journalist had applied for press accreditation three months prior but was informed on 19 September that it had been denied by police on security grounds. “Rather than provide reasons and rationale for our journalistic freedom being curtailed, the police said they would not divulge why they made their call,” Segalov wrote. The journalist has never been arrested, charged or convicted of a crime. Michael Walker, a journalist working for the left-wing Novara Media, was also barred by police from entering the conference.

On 25 October three journalists working for Echo TV in Hungary were banned from entering the country’s parliament. The parliament press office said the journalists had broken official rules multiple times by filming in areas closed to the media.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Work censored or altered” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a concerted effort by press officers at the local council to control statements made by staff to journalists. Both complained that press officers were exerting pressure on staff to change statements that reflect badly on the council.

On 4 November the Spanish newspaper El País removed a column from its website that questioned and criticised allegations of sexual harassment in the film industry against the likes of Kevin Spacey, Harvey Weinstein and Roman Polanski.

On 19 December the Malta Independent, a Maltese newspaper and publishing house, announced it would remove some online content relating to a whistleblower at Pilatus Bank due to the threat of a multi-million euro lawsuit from the bank. Pilatus Bank first threatened the independent publishing house in mid-October, with lawsuits in the USA and United Kingdom.

[/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black” style=”dashed”][vc_column_text]

CASE STUDIES

2018 WATCH LIST

Index on Censorship is especially disturbed by the five countries on the map with over 60 violations in 2017. These are:

Russia (197)

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny.

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara. At a rally in Moscow on 26 March, police detained RBC correspondent Timofey Dzyadko, Mediazona publisher Piotr Verzilov, Open Russia correspondent Sofiko Arifdzhanova, Public Television of Russia journalist Olga Orlova, Echo of Moscow journalist Alexandr Pluschev and Kommersant-FM reporter Pyotr Parkhomenko. At the same rally, Guardian correspondent Alec Luhn was detained after he took a photo of a protester being arrested. He spent more than five hours at a police station without an explanation of why he was detained. Luhn was eventually charged with participating in an unsanctioned rally, even though he showed officers his press accreditation. At least nine media workers were detained across Russia on 8 October during further protests organised by Navalny.

On 20 December photographers Andrey Zolotov and Denis Bochkarev, along with Maria Alyokhina, a member of punk collective Pussy Riot, were detained during a protest at the entrance of the FSB, the Russian federal security service. All three were taken to the nearest police station, where Alyokhina and Bochkaryov spent the night ahead of an administrative hearing.

Often referred to as the only independent radio station in Russia, Echo Moskvy was subjected to significant pressure and harassment throughout 2017, with Mapping Media Freedom verifying 15 reports against the station including one radio host stabbed, two journalists fleeing the country after threats, several detained and an American company forced to withdraw funding from the station.

Turkey

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police.

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda. At the trial of journalist Nedim Türfent, who reported on security operations in Turkey’s Kurdish majority provinces, at least a dozen people claimed they were tortured by police.

In November, Turkish journalists Ahmet Altan and Mehmet Altan’s defence attorneys were forced to leave the courtroom as their clients stood trial, accused of taking part in Turkey’s failed 2016 coup. Both brothers are prominent Turkish journalists, known for their critical reporting on president Erdogan’s regime. Without lawyers present, the court then ruled that the Altan brothers — along with four other journalists — would remain in pretrial detention. On 16 February 2018 they were sentenced to aggravated life sentences.

Belarus

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests.

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges. A wave of detentions occurred on the Belarusian holiday Freedom Day on 25 March, when 36 journalists were placed in custody. Olga Morva, Philip Warwick, Andrey Dubinin, Valery Shchukin, Katsiaryna Bakhvalava, Ihar Ilyash and Volha Davydava said they were beaten by police while under arrest. Warwick, from the United Kingdom, said he was denied the right to contact his embassy after being handcuffed and hit in the face; he spent over six hours at the police station. The apartment of journalist Maryna Kastylyanchanka, who works with human rights organisations, was searched. She was later jailed for 15 days for disobeying police and participating in the unsanctioned mass protests.

Throughout the year, 69 fines were administered to journalists for violating Article 22.9 of Belarus’ Code of Administrative Offences on the illegal production and/or distribution of media content.

Ukraine

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine.

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Three journalists were arrested in territory controlled by self-proclaimed separatists in 2017, including Ukrainian blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev, one of the few journalists contributing to western and independent media outlets in eastern Ukraine.

Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko signed a National Security and Defence Council decree in May that banned a number of Russian social media sites such as VKontakte and Odnoklassniki, along with the search engine Yandex and email service Mail.ru.

“The lack of safety for journalists in Ukraine, whether direct attacks or obstruction, remains a problem, and the level of response by the authorities is telling because too often the perpetrators go unpunished,” Vitalii Atanasov, Mapping Media Freedom correspondent for Ukraine, said. “The murder of prominent journalist Pavel Sheremet in July 2016 has not yet been properly investigated, while media workers continue to face pressure from the authorities, politicians and other influential actors. It is important to emphasise to that while the Mapping Media Freedom reflects the most disturbing and characteristic cases, it does not claim to be complete.”

Spain

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence.

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona, refused to publish a column written by Gregorio Morán in which the journalist criticised the “corrupt” regional government of Catalonia. Morán also accused the Catalan media of receiving sums of public money, adding that it was therefore no surprise to see them supporting Catalan independence.

On the day of the referendum Mapping Media Freedom recorded five separate violations of media freedom. Journalists were among the many victims of violence by heavy-handed police deployed the Spanish government, who declared the referendum to be illegal. Xabi Barrena, a journalist for the newspaper El Periódico, was assaulted by Spanish national police while reporting on voters being evicted from a polling station in Barcelona. He was struck with a baton, knocked to the ground and kicked by police.

In the days following the referendum, media violations were widespread during the protests that swept parts of the country. On 2 October, for example, Ana Cuesta and José Yelámo, reporters for television La Sexta, were surrounded by protesters who chanted “Spanish press manipulators” and “assassins” during live coverage.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

TRENDS

Threats from the far-right

The far right has a record of violating freedom of the press throughout Europe, with 24 media violations across 13 countries involving far-right groups or activists in 2017.

Twelve attempts were made by the far-right to intimidate media workers. At the start of December, the Serbian journalist Marija Antic, a television host for the broadcaster N1, received death and rape threats on social media after interviewing a French-Serbian far-right activist. Antic had invited Arnaud Gouillon, who is known for his support for Serbs in Kosovo, to her talk show. During the interview, Antic asked him about his past involvement in the French far-right group Les Identitaires and about his connections with far-right Serbian groups after he attended some of their events. After the interview, Gouillon accused Antic of demonising him. Soon after, Antic received multiple threats on social media.

On six occasions, far-right groups attempted to defame journalists throughout Europe. This was the case on 15 March when Stina Blomgren, a Swedish journalist working for the state broadcaster SVT, was accused by the popular Swedish-Russian far-right blogger Egor Putilov of lying and creating fake reports about the risks Syrian migrants faced when trying to reach Sweden. Putilov claimed to have visited Egypt and uncovered inaccuracies in an article published by Blomgren in August.

In 2017 four reports made to Mapping Media Freedom involved violence from the far right and four involved attacks to property. These ranged from damages to camera equipment to an assault with a metal pipe.

Corruption

Corruption is a major issue in the EU and neighbouring countries, undermining democracy and putting people at risk. Journalists play a key role in uncovering and fighting corruption through their investigations and, as a result, put themselves in danger. In all, 67 cases of media workers facing difficulty in their reporting on corruption were recorded throughout 2017.

On 16 August, for instance, Parim Olluri, editor-in-chief of investigative website Insajderi, was physically assaulted by unknown individuals outside his home in Kosovo’s capital Pristina. Olluri believes the attack was linked to his work. A few days before the assault, Olluri had published an editorial about corruption allegations against former Kosovo Liberation Army commanders, after which he received a torrent of abuse and threats on social media.

On 16 October the Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered when the car she was driving exploded. On 11 March Silvio Debono, owner of real estate investment company DB Group, filed 19 libel cases against her. Caruana Galizia published a number of articles on her blog discussing a business deal between the developer and Malta’s government to take over a tract of public land on which he had planned to build a Hard Rock Hotel and two towers of flats for sale. Caruana Galizia also conducted an investigation allegedly linking prime minister Joseph Muscat and his wife to the Panama Papers scandal.

Harassment of female journalists

Mapping Media Freedom logged 10 cases where women journalists reported they suffered sexual harassment throughout 2017, from politicians, anonymous sources and fellow journalists alike. In February the Swedish newspaper journalist Evelyn Schreiber was subjected to persistent death threats and threats of sexual violence after questioning local police officer a Peter Springare’s assertion that immigrants were responsible for a spike in violent crime in Örebro, Sweden. Within 24 hours of her report, Schreiber received over 200 emails containing threats.

On 7 May Loes Reijmer, a journalist and columnist for the Dutch daily newspaper De Volkskrant, faced abuse after the popular right-wing blog GeenStijl published a photo of her with the text: “Would you do her?” Thousands of readers responded in the comments section, many containing sexual references and rape threats. Reijmer had published several articles critical of GeenStijl, which is owned by Telegraaf Media Group and is one of the top 10 most popular news sites in the Netherlands.

On 30 November, Dzenan Selimbegovic, a deputy secretary general of the presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, used offensive language to describe Sanele Prašović Gadžo, a journalist for the public broadcaster BHT, and Arijana Saračević-Helać, a journalist for the public broadcaster FTV, in a Facebook post. The comments followed a trailer aired on BHT for Gadžo’s interview with Saračević-Helać on her talk show.

Commercial interference

In 2017 Index on Censorship added the “commercial interference” category to Mapping Media Freedom to monitor actions that use money and/or financial pressure to influence editorial decisions of a media or news outlet. One of the most concerning issues highlighted was the lack of plurality in media ownership in Ireland and the impact this can have on the public’s right to information.

Broadcasting in the country is dominated by just two organisations, RTÉ and Communicorp. Semi-state RTÉ services are the most popular on television and radio, while businessman Denis O’Brien’s Communicorp owns the largest commercial news radio stations – Newstalk and Today FM, among others. There is currently a lack of imperative for reform on the issue of the concentration of media ownership by the Irish government, leaving journalists open to further pressure and self-censorship to suit commercial interests, according to the National Union of Journalists.

Across Europe commercial interference in the media is proving to be a growing problem. On 6 December in Nantes, France, for example, managers of McDonald’s restaurants were asked to remove a page from local newspaper Ouest France that contained an article about litigation between the fast food restaurant chain and two of its workers, who had campaigned for union representation.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Mapping Media Freedom’s annual report highlights issues affecting the state of press freedom throughout Europe in 2017. Index on Censorship urges that the following steps be taken.

-

All journalists, media workers and others arrested for exercising their right to freedom of expression must be immediately and unconditionally released. We make this plea directly to the Turkish government in particular, which has become the largest jailer of journalists not just among the countries monitored by Mapping Media Freedom, but the entire world.

-

Laws designed to impinge on the work of journalists must be reconsidered, whether amended or abolished. This includes defamation laws, hate speech laws and terror and security-related legislation. Lawmakers should also ensure that new or revised laws do not encroach on the work of journalists.

-

Governments must respect the right of journalists to protect confidential information and sources. This is vital, especially in cases involving whistleblowing in the public interest.

-

Harassment and crimes against journalists must be properly investigated and those responsible should be prosecuted to prevent the further proliferation of impunity.

-

Governments should do more to ensure the protection of media workers who are women.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1521129408155{background-color: #d5473c !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protect media freedom”][vc_column_text]

We monitor threats to press freedom, produce an award-winning magazine and publish work by censored writers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521129253575{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MMF_2017_map-standalone.jpg?id=98665) !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.

Six journalists were killed as a result of their reporting in 2017.  Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).

Mapping Media Freedom documented 175 verified incidents of assault and injury, 109 of which occurred in just five countries: Russia (47), Spain (19), Ukraine (18), Italy (15) and France (10).  A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July

A total of 216 journalists were arrested or detained in 2017, including 21 in Azerbaijan. On 5 July  There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017.

There were 192 cases of criminal charges or civil litigation reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017.  There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In

There were 112 legal measures taken against journalists in 2017. In There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).

There were 51 reports of job loss recorded on Mapping Media Freedom throughout 2017, more than half of which came from Russia (13), Poland (8) and Spain (5).  Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the

Intimidation was widespread across Europe in 2017, with 275 incidents reported to the map. In the United Kingdom, the  There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service.

There were 109 attacks on the property of journalists in 2017. On the morning of 26 November Yulia Zavialova, editor-in-chief of the Russian investigative website Bloknot Volgograd, known for its coverage of political and business corruption, asked her father to have the tires on her car checked. Thirty minutes later he rang her to say the brakes were completely out of service.  There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.

There were 169 confirmed cases of blocked access throughout Europe in 2017, in which journalists were expelled from a location or prevented from speaking to a source by way of obstruction. Many of these reports were connected to other violations, such as assault, damage to property and intimidation.  In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a

In 2017 Mapping Media Freedom documented 81 cases in which journalists had their work censored or altered. On 15 October in the city of Uppsala, Sweden, local newspaper UNT and public broadcaster SVT identified what they saw as a  During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara.

During protests organised by Russian lawyer and activist Alexei Navalny in March and June, 1,000 people were arrested, including 19 journalists, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Makhachkala, Petrozavodsk and Samara.  Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda.

Although the number of violations reported to Mapping Media Freedom that took place in Turkey decreased between 2016 and 2017 — from 231 to 135 — the country remains the number one jailer of journalists in the world with 151 media workers behind bars by the end of 2017. In all, 65 journalists were jailed and sentenced on charges including the spreading of terrorist propaganda.  A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges.

A total of 92 violations of media freedom were recorded in Belarus throughout 2017, including the detainment of 101 journalists. In all, 30 journalists received criminal charges.  In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were:

In all, 74 violations against the media in Ukraine were reported to Mapping Media Freedom in 2017. One of the most worrying trends included the treatment of foreign journalists or journalists working for Russian companies. Sixteen journalists were expelled from, or not allowed to enter the country, including some who worked for Russian state media outlets. There were three cases involving the abuse of Interpol warrants to arrest or detain foreign journalists in Ukraine by their countries of origin as a means of silencing critical voices. These were:  Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona,

Between 2016 and 2017, media freedom violations in Spain increased from 56 to 66. Journalists experienced difficulties before, during and after the referendum on Catalan independence on 1 October. In July the daily newspaper La Vanguardia, based in Barcelona,