Thirty years on: the Salman Rushdie fatwa revisited

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Salman Rushdie. Credit: Fronteiras do Pensamento

On 14 February 1989 Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to execute author Salman Rushdie over the publication of The Satanic Verses, along with anyone else involved with the novel.

Published in the UK in 1988 by Viking Penguin, the book was met with widespread protest by those who accused Rushdie of blasphemy and unbelief. Death threats and a $6 million bounty on the author’s head saw him take on a 24-hour armed guard under the British government’s protection programme.

The book was soon banned in a number of countries, from Bangladesh to Venezuela, and many died in protests against its publication, including on 24 February when 12 people lost their lives in a riot in Bombay, India. Explosions went off across the UK, including at Liberty’s department store, which had a Penguin bookshop inside, and the Penguin store in York.

Book store chains including Barnes and Noble stopped selling the book, and copies were burned across the UK, first in Bolton where 7,000 Muslims gathered on 2 December 1988, then in Bradford in January 1989. In May 1989 between 15,000 to 20,000 people gathered in Parliament Square in London to burn Rushdie in effigy.

In October 1993, William Nygaard, the novel’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times outside his home in Oslo and seriously injured.

Rushdie came out of hiding after nine years, but as recently as February 2016, money has been raised to add to the fatwa, reminding the author that for many the Ayatollah’s ruling still stands.

Here, 30 years on, Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the issue of the fatwa, including two from Rushdie himself.

Cuba today, the March 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

World statement by the international committee for the defence of Salman Rushdie and his publishers

March 1989, vol. 18, issue 3

On 14 February the Ayatollah Khomeini called on all Muslims to seek out and execute Salman Rushdie, the author of The Satanic Verses, and all those involved in its publication. We, the undersigned, insofar as we defend the right to freedom of opinion and expression as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, declare that we also are involved in the publication. We are involved whether we approve the contents of the book or not. Nonetheless, we appreciate the distress the book has aroused and deeply regret the loss of life associated with the ensuing conflict.

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Amir Taheri

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

‘What Rushdie has done, as far as Muslim intellectuals are concerned, is to put their backs to the wall and force them to make the choice they have tried to avoid for so long’. Last year, when poor old Mr Manavi filled in his Penguin order form for 10 copies of Salman Rushdie’s third novel, The Satanic Verses, he could not have imagined that the book, described by its publishers as a reflection on the agonies of exile, would provoke one of the most bizarre diplomatic incidents in recent times. Mr Manavi had been selling Penguin books in Tehran for years. He had learned which authors to regard as safe and which ones to avoid at all costs.

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Wole Soyinka

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Reflections on an invalid fatwah

Amir Taheri

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

Broadly speaking, three predictions were made. The first was that Khomeini’s attempt at exporting terror might goad world public opinion into a keener understanding of Iran’s tragedy since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The fact that the Ayatollah had executed thousands of people, including many writers and poets since his seizure of power in Tehran had provoked only mild rebuke from Western governments and public opinion. With the fatwa against Rushdie, we thought the whole world would mobilise against the ayatollah, turning his regime into an international pariah. Nothing of the kind happened, of course, and only one country, Britain, closed its embassy in Tehran – and that because the mullahs decided to sever.diplomatic ties. In the past twelve months Federal Germany and France have increased their trade with the Islamic Republic to the tune of II and 19 per cent respectively. The EEC countries and Japan have, in the meantime, provided the Islamic Republic with loans exceeding £2,000 million. The stream of European and Japanese businessmen and diplomats visiting Tehran turned into a mini-flood after Khomeini’s death last June.

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Salman Rushdie and political expediency

Adel Darwish

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

When I reviewed Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in September 1988, it never crossed my mind to make any reference to possible offence to Muslim readers, let alone to anticipate the unprecedented international crisis generated in the months that followed. I do not think I was naive – as an LBC radio reporter suggested when she interviewed me at the first public reading from The Satanic Verses in June 1989. On the contrary, I can claim more than many that I am able to understand what Mr Rushdie was trying to say in his book, and the way the crisis has developed. Like Mr Rushdie, I am a British writer, born to a Muslim family. Born in Egypt, I was educated and am employed in Britain, and have been preoccupied and engaged, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s, with the issues that Mr Rushdie has fought for and with which he seemed to be very much concerned in his book.

Azerbaijan, the February 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Salman Rushdie

February 1991, vol. 20, issue 2

A man’s spiritual choices are a matter of conscience, arrived at after deep. reflection and in the privacy of his heart. They are not easy matters to speak of publicly. I should like, however, to say something about my decision to affirm the two central tenets of Islam — the oneness of God and the genuineness of the prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad —and thus to enter into the body of Islam after a lifetime spent outside it. Although I come from a Muslim family background, I was never brought up as a believer, and was raised in an atmosphere of what is broadly known as secular humanism. I still have the deepest respect for these principles. However, as I think anyone who studies my work will accept, I have been engaging more and more with religious belief, its importance and power, ever since my first novel used the Sufi poem Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-din Attar as a model. The Satanic Verses itself, with its portrait of the conflicts between the material and spiritual worlds, is a mirror of the conflict within myself.

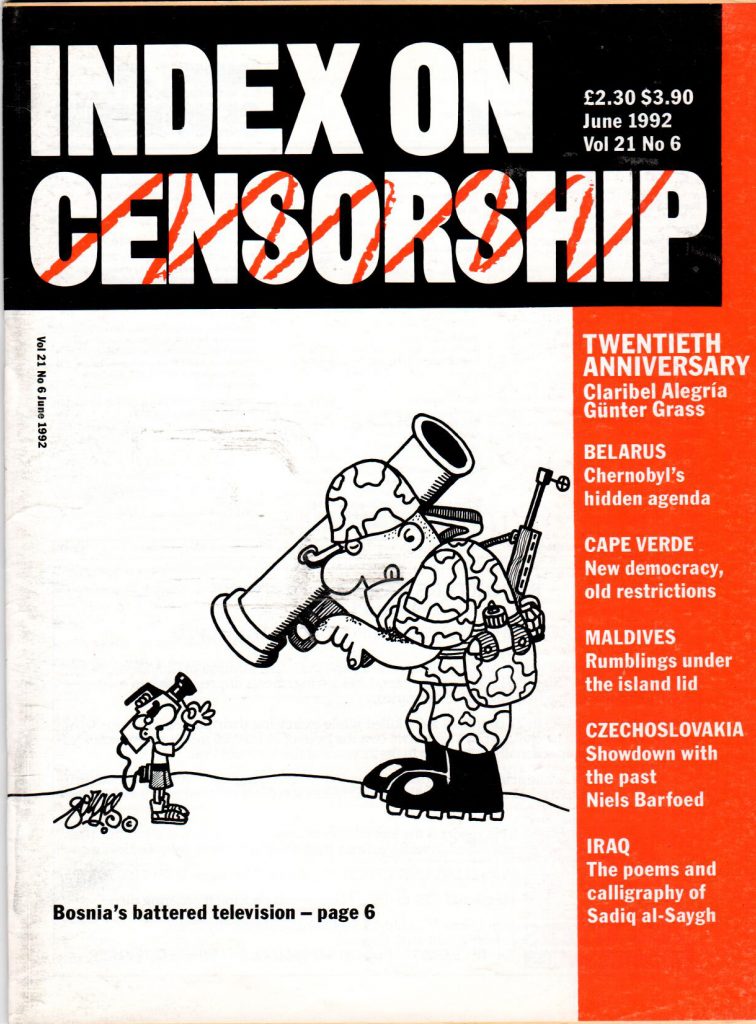

20th Anniversary: Reign of terror, the June 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Gunter Grass

June 1992, vol. 21, issue 6

When George Orwell returned from Spain in 1937, he brought with him the manuscript of Homage to Catalonia. It reflected the experiences he had gathered during the Civil War. At first, he was unable to find a publisher because a multitude of influential, left-wing intellectuals had no wish to acknowledge its shocking observations. They did not want to accept the Stalinist terror, the systematic liquidation of anarchists, Trotskyists and left-wing socialists. Orwell himself only narrowly escaped this terror. His stark accusations contradicted a world image of a flawless Soviet Union fighting against Fascism. Orwell’s report, this onslaught of terrible reality, tarnished the picture-book dream of Good and Evil. A year later, a bourgeois Western publisher brought out Homage to Catalonia; in the areas of Communist rule, Orwell’s works – among them the bitter Spanish truth – were banned for half a century. The minister responsible for state security= in the German Democratic Republic, right to its end, was Erich Mielke. During the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the Communist cadre to whom purge through liquidation became commonplace. A fighter for Spain with an extraordinary capacity for survival.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Russia’s choice, the November-December 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Rushdie affair: Outrage in Oslo

Hakon Harket

November 1993, vol. 22, issue 10

The terrorist state of Iran must face the consequences of refusing to lift the fatwa that condemns Salman Rushdie, and those associated with his work, to death. When someone, in accordance with the express order of the fatwa, attempts to murder one of the damned, the obvious consequence is that Iran must be held responsible for the crime it has called for, at least until there is conclusive proof that no connection exists. The shooting of William Nygaard has reminded the Norwegian public of what the Rushdie affair is really about: life and death; the abuse of religion; the fiction of a free mind. This war of terror against freedom of speech is not one we can afford to lose. Since the nightmare clearly will not disappear of its own accord, it must be engaged head-on.

New censors, the March 1996 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

March 1996, vol. 25, issue 2

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Kenan Malik

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

The Satanic Verses was, Salman Rushdie said in an interview before publication, a novel about ‘migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death’. It was also a satire on Islam, ‘a serious attempt’, in his words, ‘to write about religion and revelation from the point of view of a secular person’. For some that was unacceptable, turning the novel into ‘an inferior piece of hate literature’ as the British-Muslim philosopher Shabbir Akhtar put it. Within a month, The Satanic Verses had been banned in Rushdie’s native India, after protests from Islamic radicals. By the end of the year, protesters had burnt a copy of the novel on the streets of Bolton, in northern England. And then, on 14 February 1989, came the event that transformed the Rushdie affair – Ayatollah Khomeini issued his fatwa.’I inform all zealous Muslims of the world,’ proclaimed Iran’s spiritual leader, ‘that the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses – which has been compiled, printed and published in opposition to Islam, the prophet and the Quran – and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its contents are sentenced to death.’

Peter Mayer

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Penguin published Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses six months before Ayatollah Khomeini issues his fatwa. When we decided to continue publishing the novel in the aftermath, extraordinary pressures were focused on our company, based on fears for the author’s life and for the lives of everyone at Penguin around the world. This extended from Penguin’s management to editorial, warehouse, transport, administrative staff, the personnel in our bookshops and many others. The long-term political implications of that early signal regarding free speech in culturally diverse societies were not yet apparent to many when the Ayatollah, speaking not only for Iran but, seemingly, for all of Islam, issued his religious proclaimation.

Bernard-Henri Lévy

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Salman Rushdie was not yet the great man of letters that he has since become. He and I are, though, pretty much the same age. We share a passion for India and Pakistan, as well as the uncommon privilege of having known and written about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (Rushdie in Shame; I in Les Indes Rouges), the father of Benazir, former prime minister of Pakistan, executed ten years earlier in 1979 by General Zia. I had been watching from a distance, with infinite curiosity, the trajectory of this almost exact contemporary. One day, in February 1989, at the end of the afternoon, as I sat in a cafe in the South of France, in Saint Paul de Vence, with the French actor Yves Montand, sipping an orangeade, I heard the news: Ayatollah Khomeini, himself with only a few months to live, had just issued a fatwa, in which he condemned as an apostate the author of The Satanic Verses and invited all Muslims the world over to carry out the sentence, without delay.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1623240200822-8c1bcd36-9835-10″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]