Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

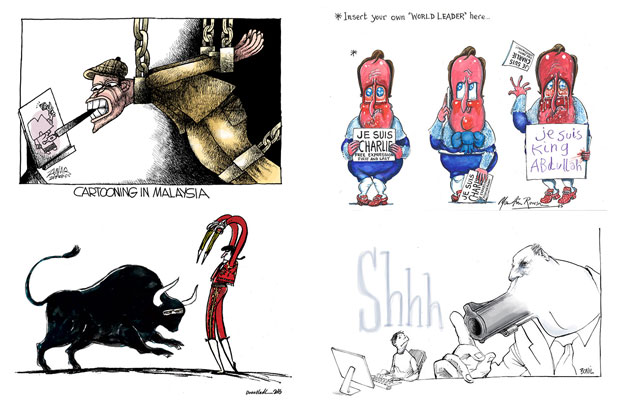

Among the cartoons available in the auction are original artworks by Zulkiflee Anwar Haque (Zunar); Martin Rowson; Xavier Bonilla (Bonil); and Doaa El Adl (clockwise from top left).

Index on Censorship is delighted to announce the auction of an incredible collection of cartoons that celebrate the power of art to challenge suppression. The auction will help fund our work supporting persecuted writers and artists worldwide.

Make a new donation to Index before the end of December to receive a limited-edition postcard set of 10 cartoons created by some of the world’s top political cartoonists

Earlier this year, Index commissioned 10 of the world’s leading cartoonists to pen a work on the theme of free expression. The cartoons are powerful tributes to the role of art, drawn by world-renowned artists from every continent: from a US Pulitzer Prize winner to a Syrian cartoonist beaten in retaliation for his work.

Beginning Tuesday, 24 November 2015, bidders will be able to enter bids for hand-drawn artwork by:

Xavier Bonilla (Bonil) – Ecuador

Regularly denounced, threatened and fined, Ecuador’s Bonil has earned the title “the pursued cartoonist” for his work. For 30 years he has critiqued, lampooned and ruffled the feathers of Ecuador’s political leaders, in the process earning a reputation as one of the wittiest and most fearless cartoonists in South America.

Kevin Kallaugher (Kal) – United States

US artist Kal is the editorial cartoonist for The Economist and The Baltimore Sun and his work has appeared in more than 100 publications worldwide including Le Monde, Der Spiegel, The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and The Washington Post. He has won numerous awards, including the 2014 Grand Prix for Cartoon of the Year.

Signe Wilkinson (Signe) – United States

The first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning, Signe has won several other awards for her work. She comments on topical political issues and is best known for her daily cartoons in The Philadelphia Daily News.

Jean Plantureux (Plantu) – France

Plantu is the chief cartoonist for France’s Le Monde and founder of Cartooning for Peace, a global network of cartoonists. This drawing is a rare, signed copy of the world-famous cartoon Plantu drew for Le Monde the day after the attack on Charlie Hebdo.

Martin Rowson – UK

A former Cartoonist Laureate, political satirist Martin Rowson contributes cartoons to The Guardian and the Daily Mirror as well as Index on Censorship magazine. His work has earned him several awards, including the prize for the Best Humour and Satire Book of the Year at this year’s Political Book Awards.

Ali Farzat – Syria

Ali Farzat, a former Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award winner, came to global attention in 2011 when he was pulled from his car and beaten by Syrian security forces who broke both his hands. When Kuwaiti authorities closed the offices of his newspaper, Al-Watan, earlier this year Ferzat was forced to buy new materials and redrew this cartoon for us from scratch.

Doaa El Adl (Doaa) – Egypt

Doaa is a celebrated female artist in the Arab world – well know for her fearless political work. She has often tackled freedom of speech, human rights and women’s rights issues, wining numerous awards as well as controversy and even charges of blasphemy for her work.

Zulkiflee Anwar Haque (Zunar) – Malaysia

Zunar is an award-winning Malaysian political cartoonist who has been repeatedly targeted by authorities. Five of his cartoon books have been banned by the Malaysian government for carrying content “detrimental to public order” and thousands confiscated. He is currently facing up to 43 years in jail for mocking the government.

David Rowe – Australia

A three-time winner of the Stanley Award for Australia’s Cartoonist of the Year, David Rowe has worked for the Australian Financial Review for 22 years. Rowe’s bright and colourful watercolours are famously merciless.

Damien Glez – (Glez) – Burkina Faso

Glez’s cartoons regularly appear across three continents, including his own weekly satirical newspaper in Burkina Faso: Le Journal du Jeudi . He co-created pan-African monthly satirical Le Marabout, writes his own comic strip Divine Comedy and has won numerous awards internationally..

Bids must be placed by noon on Monday, 14 December 2015.

The auction is being hosted by Givergy.

This is the first of two posts by Farida Ghulam, an advocate for freedom of speech, human rights and democracy. Ghulam has campaigned for women’s rights and is currently active in the push for democratic reforms in Bahrain. Her husband, Ebrahim Sharif, who is a former Secretary General of the National Democratic Action Society (WAAD), is currently in detention awaiting trial on charges of charges of inciting hatred and sectarianism and calling for violence against the regime. He faces 10 years for expressing opinions in a speech marking the memory of a 16-year-old killed while protesting against Bahrain’s government.

Among the countless stories of suffering that the Bahraini people have endured is the story of my own family: one of hardship, sacrifice and pure injustice. My husband was arrested, incarcerated for four and a half years, released for three weeks, and promptly re-arrested.

Those three weeks were beautiful and magical. They were surreal. It’s like what Ebrahim said when his daughter landed in Bahrain and woke him up the morning after his release. He asked her: “It’s like a dream, isn’t it?” Those three weeks passed by so quickly that they don’t seem real; we’ve now plunged back into our old routines of monitored visits, monitored and limited phone calls, court hearings, and the anxiety inherent in facing a long dark tunnel with very little light ahead.

My husband and I, along with our political party, the National Democratic Action Society (also known as WAAD), have been advocating for democracy, fighting corruption, and highlighting social injustice in the Kingdom of Bahrain for a long time now. My husband, Ebrahim Sharif, is the former Secretary General of WAAD, and has run twice for a seat in Bahrain’s Parliament. During his campaign he was able to gain traction with the people of Bahrain by raising awareness of social and economic corruption, as well as stressing shortcomings of the current political system and proposing needed reforms to build a true democracy. His campaign focused on the people being the source of any government’s power, a statement which is ironically featured in Bahrain’s constitution. He challenged the government in many economic and political domains, using his skills in finance and economics to easily prove the existence of corruption and discrimination.

The courage Ebrahim showed by exposing the government in such public ways understandably threatened the establishment, especially considering that he is a Sunni man, the same religious sect as Bahrain’s ruling elites, which made him difficult to discredit along sectarian lines. Ebrahim’s point of view, along with the points of view of other prominent opposition figures in Bahrain, were never addressed by the ruling powers, although these views were supported by the majority of Bahrain’s people. The only responses that addressed these views were smear campaigns placed in pro-regime newspapers and TV networks.

After witnessing developments in Tunisia and Egypt during the Arab Spring in 2011, the Bahraini people took to the streets in peaceful demonstrations against the government. They set up a home base around Pearl Roundabout, in central Manama. It happened quickly and naturally, with no prior planning by opposition groups, which joined the mass movement a few days later by attending and giving speeches focused on peacefulness as a strategy in expressing the political demands addressed to the government. My husband was one of these opposition leaders, where he spoke about what a true constitutional monarchy means and reiterating the views of his parliamentary campaign which promised to put power in the people’s hands by raising awareness and insisting on non-violent measures to obtain the necessary changes for democratic advancement.

The government responded to this movement by cracking down a month later, sending in GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) troops, tanks, tear gas and weapons. Many people were killed in the ensuing chaos and arrests of political leaders occurred over the following days. The roundabout was demolished by the government in an attempt to quickly erase the movement from people’s memories and history and exploit their declaration of martial law as an excuse to regain control and quell the protests entirely.

My husband’s first arrest was an exercise in torment — solitary confinement, torture in the form of mass beatings by masked police, sleep deprivation, forcing him to sleep on cold-water soaked mattresses in incredibly cold air-conditioned rooms, constantly barking dogs, sexual harassment and threats, whipping with plastic pipes, insulting his family’s honor, and standing for long hours with hands held vertically in the air. At one point, he was beaten and threatened that if he issued a complaint to the military prosecution, he would be beaten again. Ebrahim filed the complaint, the man indeed kept his promise and Ebrahim was beaten again. To add to that, on the day that the military judge issued the verdict of guilty, all of the political leaders were taken to a back room in the courthouse and beaten because they had chanted the words “peacefulness, peacefulness” in response to the judge’s verdict and sentences.

We have been telling our story over and over again from 2011. Ebrahim was sentenced to 5 years in prison, while the other political figures, part of the “Bahrain 13”, a group of political leaders which the Bahraini government alleges Ebrahim is a member of, received longer sentences ranging from 10 years to life imprisonments. In June of 2015, Ebrahim was released on a royal pardon, only to be re-arrested a mere three weeks later on 12 July due to a speech he gave commemorating the death of a 16-year-old martyr who was barbarically shot at close range by police in 2012 and who received no justice.

As a family, we’ve decided that it would be important for us to write about the hardships we have personally endured on an individual and family level as a direct consequence of the punishment handed down by the government, which fears the pure and peaceful expression of speech. The right to freedom of speech is recognized worldwide by an endless array of organizations, and while Bahrain claims to respect the International Declaration of Human Rights, it is abundantly clear that it does not. While the Kingdom of Bahrain is a signatory of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, what has happened to Ebrahim and other Bahrainis opposing the injustice and discrimination in the country proves the kingdom does not hold these covenants in high regard.

This piece is intended as an informative introduction to what Bahrain has gone — and continues to go — through, as well as what we personally have gone through as a family, and to have it as a basic reference before reading the next piece which will highlight the family’s emotional struggle with losing a father and husband to an unjust sentence.

This article was posted on Thursday 26 October 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

UPDATE: Following the attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015, including the murder of 89 innocent concertgoers at Le Bataclan theatre, the Eagles of Death Metal have been added to the Music in Exile Fund playlist.

With the release of They Will Have To Kill Us First — Johanna Schwartz’s award-winning new documentary about Malian musicians who stood up to Islamists — comes the launch of the Music In Exile Fund, which will raise money to help musicians facing censorship globally.

Given the treatment of music by governments of all types from the early 20th century until today, it is clear to see it is a medium of real power. It can change minds and spread ideas. Works have been banned and artists imprisoned and sometimes even killed. In some cases, musicians flee their home country or are banned from entering another.

Here is our celebration of music and musicians who have provoked debate, censorship or worked despite society’s disapproval. Listen to our playlist of some of the best songs and artists from this group of determined musicians.

1) Erwin Schulhoff – String Quartet No. 1

Jewish artists suffered under Hitler’s persecution. Dozens of composers were killed. Fortunately, much of Erwin Schulhoff’s work has survived for later generations. Schulhoff briefly studied piano with Debussy, and was awarded the Mendelssohn Prize in 1913 for his piano achievements and again after World War I for his compositions. He was sent to Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1941 and died in the Salzburg concentration camp in 1942.

2) George Formby – When I’m Cleaning Windows

Before Elvis sent shockwaves through the music world with a swivel of his hips, George Formby was going head-to-head with censors for his use of innuendo. Compared to the expletive-laden music that tended to come up against censors later in the century, Formby was relatively mild. The ukulele player from Wigan found himself on the BBC banned list for lyrics like: “Pyjamas lyin’ side by side, Ladies nighties I have spied, I’ve often seen what goes inside, When I’m cleanin’ windows.”

3) Victor Jara – El Lazo

Victor Jara is one of the best-known musicians to have paid the ultimate price for being outspoken and critical of a despotic regime. The a folk singer, theatre director and communist party member was taken prisoner during the coup by General Augusto Pinochet. He was tortured, beaten and made to play Russian roulette before being executed on 16 September 1973. Over 40 years after his murder, 10 of the alleged perpetrators were finally brought to justice.

4) Sir Paul McCartney & Wings – Give Ireland Back To The Irish

In January 1972, Paul McCartney was moved by the events of Bloody Sunday in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, when British soldiers killed 14 civil rights protesters. His anger turned into Give Ireland back To The Irish, released a month later, and was the first single by Wings. Given the political tensions of the time, the song was banned by BBC, both on the radio and television.

5) Crass – Where Next Columbus?

Anarcho-punk ensemble Crass had a penchant for catchy album titles. Penis Envy, their 1980 release is a fairly typical example. Many record stores in the UK wouldn’t sell the album after one store was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act for stocking it.

6) Fela Kuti – Colonial Mentality

Fela Kuti is one of Nigeria’s most influential and outspoken musicians. His political campaigning was so effective that he was arrested 200 times, and once sentenced to five years in prison by a military court for currency smuggling. Amnesty International campaigned for his release, calling him a prisoner of conscience. He served a year and a half of the sentence and always protested his innocence.

7) Stiff Little Fingers – Beirut Moon

Stiff Little Fingers are the band that epitomised punk’s anti-sectarian message in Northern Ireland. But their politics spread much wider than the six counties. The first single from their 1991 Flags and Emblems album was withdrawn from sale on the first day of release because it criticised the British government for not acting to free journalist, writer and broadcaster John McCarthy, who had been held during the in the Lebanon hostage crisis

8) Frankie Goes To Hollywood – Relax

When BBC DJ Mike Read pulled Relax from the airwaves, criticising it for being overtly sexual and “disgusting” he probably didn’t think he would be making history. The song we all know today became the seventh biggest selling single of all time, and the publicity over the controversy couldn’t have hurt. A really good example of how censorship often backfires. Frankie says relax!

9) Body Count – Cop Killer

During the 1990s, American politicians — while divided on many things — seemed united in their distaste of rap. From Democrat Tipper Gore riffing on it in Congress to Republican President H.W. Bush calling it “sick, Ice T’s Cop Killer was public enemy number one. It was subsequently pulled from his metal band Body Count’s debut album.

10) Lavon Volski – Starszynia

Lavon Volski is an icon, not only of rock music in Belarus but of the country’s opposition movement. It is probably of no surprise then that under the current government in Belarus, the guitarist and singer, along with his group Krambambulya are blacklisted.

11) Tyler The Creator – Yonkers

Rapper Tyler, The Creator, was barred from entering the UK in August this year for a period of three to five years due to his controversial lyrics. The Home Office claimed the rapper’s music “fosters hatred with views that seek to provoke others to terrorist acts” and “encourages violence and intolerance of homosexuality.” Tyler will be the first-ever musician to be banned from the UK because of lyrical content — effectively considering an artist on par with a terrorist or hate-preacher.

12) El Haqed – Dawla

Mouad Belghouat is a Moroccan rapper and human rights activist who releases music under the moniker El Haqed. His music has publicised widespread poverty and endemic government corruption in Morocco since he sang Stop the Silence in 2011 and galvanised Moroccans to protest against their government. He has been imprisoned on spurious charges and is banned from performing or releasing music in his home country.

13) Songhoy Blues – Soubour

Songhoy Blues are an energetic band from Mali with inspiring beginnings. They fled their homes as refugee in the north of the country when Islamists took over. All four musicians met each other for the first time when they reached the safety of Bamako and, having decided they couldn’t remain silent, formed a band. Their music and story feature heavily in the film They Will Have To Kill Us First.

14) Ramy Essam – Foul Caviar

Ramy Essam was the voice of the Egyptian revolution which began in 2011. In just under three weeks at Tahrir Square, he found fame. His song Irhal, in which he urged Hosni Mubarak to step down, gained great popularity among the demonstrators. When the army moved in to clear the square, he was arrested and subsequently tortured. In October 2014, Essam was offered safe residence in Sweden for two years.

15) Ikonoklasta – Revolução

Luaty Beirão, aka Ikonoklasta, is a 33-year-old Angolan revolutionary rapper known for his politicised lyrics and criticism of the government. But since June, he has been in prison on charges of plotting to overthrow President Eduardo dos Santos. Beirão is currently on a hunger strike and, according to his family, in critical condition.

16) Eagles of Death Metal – So Easy

On 13 November 2015, the Eagles of Death Metal were playing a sold-out concert at Le Bataclan theatre in Paris when the venue was attacked by terrorists, who killed 89 concertgoers. The attackers shot randomly into the crowd and detonated explosive vests. All band members survived. However, 36-year-old Nick Alexander, who worked the band’s merchandise table, was among those killed.

You can donate to the Music In Exile Fund here.

This article is part of the spring 1987 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by children’s book author Norma Klein, on the censorship of children’s books, taken from the spring 1987 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Banned books: controversy between the covers session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

I used to feel distinguished, almost honoured, when my young books were singled out to be censored. Now, alas, censorship has become so common in the children’s book field in America that almost no one is left unscathed. Some of the most conservative writers are being attacked; it’s reached a point of ludicrousness which, for me, was symbolised by my most recent encounter with ‘the other side’ in Gwinett county, Georgia, in April 1986.

Usually, my books are attacked for their sexual content. The two school board meetings I had attended in the early 1980s, one in Oregon, one in the State of Washington, had centred on two books for older teens, It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, a book about two 18- year-olds having a love affair, and Breaking Up, a novel about a 15-year-old girl who discovers her mother is gay. I might add parenthetically that these books have just been published in England for the first time by Pan Books in a new series aimed at teenagers, ‘Horizons’. Already, as in America, they are selling well and already, as in America, I have been told of indignant parents storming into bookstores and objecting to certain passages. It seems that things are not very different in other countries.

What was unusual about the Gwinnett county case was that the book selected to be attacked was one of my early ones, Confessions of an Only Child, about an eight-year-old girl. The offending sentence was one where the girl’s father is putting up wallpaper. Here it is in its entirety:

‘God damn it,’ Dad said as the wallpaper swung around and whacked him in the face.

When the paperback publisher of Confessions first heard of the attack, he attempted to defend the book in the following way:

Abrasive words are sometimes used by writers to add definition to a character or a story; they give the reader an understanding of the situation or kind of person speaking, but are not meant to be words which the reader should use or admire. It is our belief that the family relationships are so positive in this book that they far outweigh the use of realistic language.

My attacker, Theresa Wilson, a stunning blonde, had been heartened by her success in having another book she objected to, Deanie by Judy Blume, removed from the shelves. Her first attempt to remove my book was defeated by a 10-member review panel consisting of six parents, three teachers and a librarian. Ms Wilson claimed to have ‘stumbled’ upon the offending passage one afternoon while in the Beaver Ridge library looking for books that contain material to which she might object. In her thirties, she has no profession and, in a sense, being a censor has led to her becoming a local celebrity; she now, whether her attacks succeed or fail, appears regularly on TV and radio and is covered widely in local newspapers. The 10-member panel voted to keep Confessions on the shelves; only one person voted to keep it on a restricted shelf. ‘The consensus is that the book had literary merit for the age group intended,’ said principal Becky Hopcraft.

Incidentally, Ms Wilson said she didn’t object to my heroine’s mother saying, ‘Ye Gods,’ in the next line, because she does not believe ‘Gods’ refers to the Christian god. She wants every book containing the word ‘damn’ restricted from Gwinnett elementary schools. She cited a US Supreme Court ruling against hostility toward religion and said the use of God Damn in Confessions indicated a ‘hostility toward Christianity’.

All this, the initial attack on my book and its initial success in being retained on the shelves, helped to achieve an important result — the founding of a group called Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education. Initially a small group, it now has nearly 500 members. Its president, Lorna Cox, said she was amazed at the diversity of the group’s members, proving that liberals in America are not, as some right-wingers insist, an elitist minority. ‘We’ve got people who didn’t graduate from high school,’ Ms Cox said, ‘college graduates, doctors, professionals, and people who aren’t even affiliated with a school but have a deep, burning desire to be involved in education.’ The group participates in workshops to learn more about censorship at the local and national levels and contacts school administrators each week to learn about potential book bannings.

As in the cases involving It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, and Breaking Up, my travel expenses to Georgia were paid by the author’s organisation, PEN. They have a Freedom to Read committee with a fund for cases like this. My own reason for attending these meetings is that I feel having the author appear and help argue the case not only gives heart to the local anti-censorship organisations involved, such as Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education, but may focus national attention on the case. Perhaps it was co- incidental, but CBS did appear in the courtroom to cover the debate for a TV segment on ‘secular humanism’.

Before flying to Georgia I was interviewed by phone. I was quoted as saying, ‘I’m not a religious person… To me the phrase god damn has no more negative a connotation than the expression, Oh gosh. I added that I attributed the swing toward censorship in America to the conservative mood of the Reagan administration. When I arrived, I was told by two of my supporters that the negative reference to Reagan was a mistake. ‘Everyone is for him down here,’ they said. I have to add parenthetically that one of the reasons I write the kinds of books I do and am, perhaps ingenuously, surprised at the reaction they provoke, is due to the fact that I’ve lived all my life in New York City and know personally only liberal people. I’ve never met anyone who voted for Reagan; I am always amazed when the Republicans win an election. But it’s probably similar that in a two-week stay in London’ in the spring of 1986,1 didn’t meet anyone who was for Margaret Thatcher either. This may, however, give me a kind of inner freedom from certain restrictions, due simply to underestimating the power of the right.

The school board meeting I attended was crowded with supporters from both sides. It was conducted as a kind of mock trial. Both sides were allowed to question anyone from the other side about anything that was relevant to the case. I was pleased and relieved that every time Ms Wilson tried to bring the questioning around to my own personal religious beliefs, she was told that was not relevant to the book. In a perverse way I found her performance at the trial fascinatiing. She alternately flirted with, and tried to antagonise, the three-member school board which consisted of two men and a woman. Luckily for me, her case was weak and she overstepped the bounds of tolerance — even within a conservative, religious community — by telling the school board members that if they didn’t ban my book, they would, on Judgment Day, go straight to Hell. ‘One day each and every one of you will stand before God almighty and you will answer to how’you believe, how you voted, how you stand.’ Evidently this threat did not frighten anyone sufficiently.

The closest Ms Wilson got to making me come forward and state my personal beliefs was when she asked if I considered myself to be ‘above God’. I responded, ‘I assume that’s a rhetorical question.’ She laughed nervously and said she didn’t know what ‘rhetorical’ meant.

Confessions of an Only Child is about a family in which the mother gets pregnant and loses her baby. It shows how this affects the heroine who was enjoying her only child status. In deciding that Confessions had ‘redeeming educational value’, one of the board members, Louise Radloff, stated, ‘I think this book has much literary merit and it shows an open discussion within the family’. I had argued in my presentation that I felt that books could be an avenue to open discussion… a way to bring parents and children closer together, that simply having a book available was not forcing it on anyone.

What amazed me, though, was that in their closing remarks, though each school board member re-iterated the literary values of my book, all three said that, indeed, the phrase ‘God damn’, was offensive and should have been left out. One board member said he, thank heaven, had never used that word. Another said he had used it once, at the age of 10 and had been beaten so severely by his parents for this that he had never used it again. I am utterly unable to judge the sincerity of these remarks. What I did feel was the pressure on everyone living in these suburban communities to conform to what is felt to be a general set of beliefs. People are terribly afraid to come out and say they are feminists, atheists, or even, God forbid, Democrats.

In a sense this is a success story. Not only will my book remain on the shelves, but the Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education feel heartened that the positive publicity they received will help them in future battles. But Theresa Wilson is, seemingly, not daunted. She’s already after another book, Go Ask Alice. ‘I don’t love publicity,’ she said when interviewed on a local radio show the day after the hearing. ‘I love showing the glory of God.’ Sadly, even the local people who are against her regard her as good copy. Although she had lost her case, she was brought forward to be on the radio show with me and most of the time was spent, not debating the issues involved, but in baiting her with peculiar call-in questions from the audience. What a pity. But still, no matter how absurd and tiny this one case is, I feel I would do it again for my own books and would encourage other authors to do the same. Passivity and inaction only encourages censorship groups even more. I think now they are beginning to realise they will, at least, have a fight on their hands.

Reporting the Third World

World leaders, or their top ministers, in an effort to arrive at something we call ‘balanced coverage’. Most Third World leaders feel you are either for ’em or against ’em and there is not much middle ground to walk upon. Some, as in Saudi Arabia, just don’t want to talk to the Western press. I can remember one visit to the Saudi kingdom in early 1981 when four American correspondents — from the New York Times, Time magazine, the Associated Press, and myself from The Washington Post — jointly applied for an interview with either King Khalid or Crown Prince Fahd. Each of us knew it was unlikely either would bother with an interview for just one publication, but here was a broad segment of the US print media asking collectively for an interview. After waiting around for two weeks, we collectively gave up and left.

One major problem for American correspondents is the near total ignorance of Third World leaders about how the Western media work and how to use them for their own ends. While the correspondent may regard his or her request for an interview with a leader or top minister as a chance to air their views, they seem to look upon it as a huge favour which they are uncertain will be rewarded in any way.

Other forms of indirect censorship come in control over a correspondent’s access to the story or means of communication. Israel restricted, or at least tried to restrict, access to southern Lebanon after its invasion in June 1982 to those it felt were sympathetic to its cause or important to convince of its view. The policy never really worked because correspondents could always get into Israeli-occupied territory from the north through one back road or another. But it got more difficult as time went on. The Israeli attempt at restricting access to southern Lebanon was hardly the worst example of this kind of censorship I experienced in nearly two decades of working in the Third World, however. Covering the war between Iran and Iraq was, and remains, far more difficult. In four years, I never once got a visa to Iran. I got to Baghdad several times, but imagine my surprise the first time customs officials seized my typewriter at the airport and told me I would have to get special permission from the Information Ministry to bring it in. (At the airport in Tripoli there was a roomful of confiscated typewriters the last time I visited there in September 1984.) Whether one was allowed to the Iraqi war front depended on either an Iraqi victory or a lull in the war. As for permission to travel into Iraqi Kurdistan, it was never granted to any Western correspondent I can think of in the four-to-five years I was covering the Middle East.

The other game Iraqi information officials play is attempting to censor your coverage of the war. When I first went there, there was a Ministry of Information official sitting at the hotel who had to okay your copy or you could not send it out by phone or telex. This kind of direct censorship of copy was rare in my experience, however. Other than Israel, where military news is supposed to pass through the censor’s office, and Iraq and Libya, I can think of no examples where I had to submit my copy before sending it.

Are the techniques of indirect censorship getting worse? In the areas of the world where I have worked, I am not sure. If Syria has become worse, Iraq is probably better today. Egypt has definitely got better, and so had Kuwait until recently. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has restricted access to a far greater degree in the past two years, and Bahrain has become more sensitive. South Africa has taken a turn for the worse. Countries that were always difficult to cover, such as Zaire, Malawi, Ethiopia and Angola, remain more or less the same.

As economic problems have got worse or rulers have felt a greater threat to their regimes, Third World governments seem to be tightening up when it comes to outside press coverage.

If this is indeed the underlying principle governing the degree of press censorship, then the problem may be more cyclical than linear, getting worse or better according to the political and economic health of a country or the special challenges it is facing at that time.

Who believes it?

‘That is how the theory goes: Restrict the press to supportive comment, and a country’s life will be calmer and better. But experience and reason suggest that the opposite will happen. Faulty government policies, if they are not subject to real criticism, grow worse. Autocrats become more autocratic. Can anyone believe that repression of criticism leads to efficiency in a society, to new ideas?’

Anthony Lewis, The New York Times, February 1987

© Norma Klein and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the spring 1987 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.