11 Sep 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, Press Releases

Index on Censorship, la Fédération europénne des journalistes et Reporters sans frontières sont heureux d’annoncer l’expansion et la refonte de Mapping Media Freedom, qui recense les menaces contre les journalistes en Europe et qui couvrira désormais la Russie, l’Ukraine et la Biélorussie.

D’abord lancée en mai 2014, la carte intéractive documente les violations de la liberté de la presse dans l’Union européenne et les pays voisins, dont les Balkans et la Turquie.

Plus de 700 rapports ont été enregistrés lors de la première année d’existence du projet, révélant des menaces quotidiennes à l’encontre de la liberté de la presse, rarement signalées ou documentées par le passé.

Selon Jodie Ginsberg, directrice d’Index on Censorship : “Mapping Media Freedom a révélé le type de menaces qui pèsent contre les organisations de presse et leurs employés chaque jour en Europe. Cela va de la simple intimidation aux menaces de violence, à l’emprisonnement et même jusqu’au meurtre. Disposer d’une base de données listant ces incidents — dont la plupart étaient jusque là très peu couverts — nous permet ainsi qu’à d’autres de passer à l’action contre les coupables.”

La plateforme se veut participative et aidera les décideurs politiques et les activistes à identifier des tendances menaçant la liberté de la presse et à répondre de manière efficace en offrant leur aide ou en se mobilisant autour de problèmes spécifiques.

“A un moment où la liberté d’informer subit des menaces qui n’ont pas été constatées depuis l’époque de l’Union soviétique, il est essentiel de soutenir les journalistes et les blogueurs. Alors qu’une partie du continent sombre dans une dérive autoritaire, la surveillance en ligne est devenue un défi commun,” déclare Lucie Morillon, directrice de programmes à Reporters sans frontières.

Suite à un renouvellement du financement de la Commission Européenne plus tôt cette année, la plateforme comprend de nouvelles propriétés, notamment une fonction de recherche améliorée. Le projet a également pour ambition de forger de nouvelles alliances entre journalistes à travers le continent, particulièrement parmi les jeunes journalistes qui trouveront des ressources utiles et des articles approfondis sur la page “Libérez les médias !”

La refonte de la carte la voit s’étendre à la Russie, à l’Ukraine et à la Biélorussie suite à de nouvelles mesures restreignant la liberté de la presse de manière draconienne dans cette zone, et suite au conflit qui a éclaté en Ukraine.

“L’extension du projet à l’Ukraine, à la Russie et à la Biélorussie est une bonne nouvelle pour les journalistes et les personnes travaillant pour des organismes de presse dans la région. Les journalistes sont généralement au coeur de manifestations, d’affrontements violents et de conflits armés où ils courent le risque d’être blessés, enlevés, arrêtés, victimes de violence ou tués. Ils sont soumis à des défis professionnels difficiles, émanant notamment d’extrémistes et d’agents de propagande. En étroite collaboration avec ses partenaires, la FEJ continuera à documenter toutes les violations contre la liberté de la presse et à se mobiliser quand elles ont lieu”, dit Mogens Blicher Bjerregård, Président de la Fédération européenne de journalisme.

Les partenaires et les organisations associées au projet, dont Human Rights House Ukraine, Media Legal Defence Initiative et European Youth Press, travailleront ensemble pour s’assurer que les menaces croissantes à l’encontre de la liberté de la presse dans la région sont constamment signalées et combattues.

Pour plus d’information, merci de contacter Hannah Machlin, responsable du projet : [email protected], +44 (0)207 260 2671

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

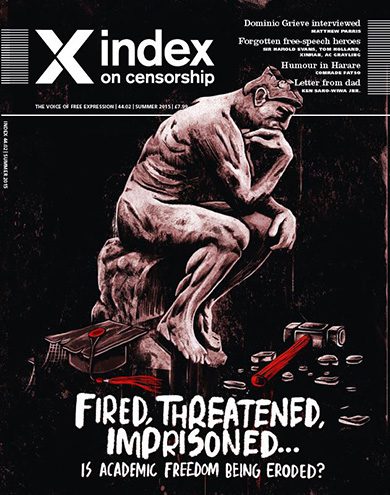

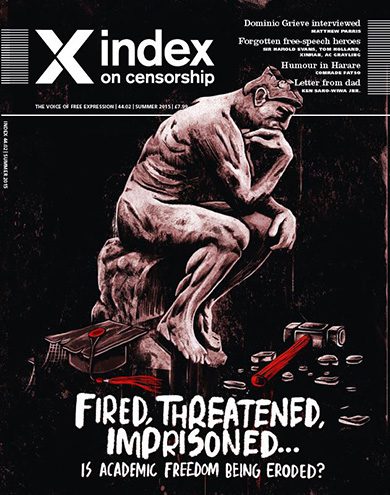

6 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

[vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495013730355{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column css=”.vc_custom_1474781640064{margin: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477669802842{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;}”]CONTRIBUTORS[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495013737805{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781919494{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Karim Miské” title=”Novelist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89017″]Karim Miské is a documentary maker and novelist who lives in Paris. His debut novel is Arab Jazz, which won Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 2015, a prestigious award for crime fiction in French, and the Prix du Goéland Masqué. He previously directed a three-part historical series for Al-Jazeera entitled Muslims of France. He tweets @karimmiske[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781952845{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Roger Law” title=”Caricaturist ” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89217″]Roger Law is a caricaturist from the UK, who is most famous for creating the hit TV show Spitting Image, which ran from 1984 until 1996. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Observer, The Sunday Times and Der Spiegel. Photo credit: Steve Pyke[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781958364{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Canan Coşkun” title=”Journalist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89018″]Canan Coşkun is a legal reporter at Cumhuriyet, one of the main national newspapers in Turkey, which has been repeatedly raided by police and attacked by opponents. She currently faces more than 23 years in prison, charged with defaming Turkishness, the Republic of Turkey and the state’s bodies and institutions in her articles.[/staff][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” css=”.vc_custom_1474815243644{margin-top: 30px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 30px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1474619182234{background-color: #455560 !important;}”][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white”]Editorial

Editor Rachael Jolley explains why the latest Index on Censorship magazine is focusing on academic freedom, with a look at current threats from around the worldwide, from Ukraine to the US.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720631074{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495014070302{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CoverSummer2015-395.jpg?id=66714) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495014100679{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Contents

A look at what’s inside the summer 2015 issue[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720637924{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495014924277{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ED374B.jpg?id=66760) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495014943674{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Open Letter

We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1491994247427{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493814833226{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495015219307{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/AD463W.jpg?id=67090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495015028084{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Fear of terror and offence

From a government crackdown on extremism to marketing departments’ concerns over branding, lecturer Thomas Docherty looks at the threats to the tradition of free discussion on campus.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815095611{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495015200298{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Zambezi-News-Season-2-Cast.jpg?id=67451) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495015141985{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwean artist and satirist Samm Farai Monro aka Comrade Fatso outlines the growing satire scene in Zimbabwe and the dangers he and fellow comedians face from government crackdowns.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815155369{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495015289971{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Morgan-pic-1.jpg?id=67255) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495015352306{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Round-the-world tour of censorship

Ann Morgan’s challenge to read a book from every country in the world led her to discover a host of censored writers.

3 May 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including Fired, threatened, imprisoned…

Subscribe now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Sep 2015 | Academic Freedom, Magazine, mobile, Student Reading Lists

To tie in with the release of Index on Censorship magazine’s summer 2015 issue on academic freedom, Index put together a reading list of articles looking at the issues surrounding freedom of speech in universities from all over the world. Highlights include Kaya Genc’s examination of the Turkish universities that are restricting professors’ rights to teaching certain portions of history and Duncan Tucker’s look at the academics and students facing death threats in Mexico. There are also testimonies from young women who faced obstacles to getting an education.

All of these articles are taken from the special report of the summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Students and academics can browse the Index magazine archive in thousands of university libraries via Sage Journals.

Academic freedom articles

Silence on campus: How a Turkish historian got death threats for writing an exam question by Kaya Genç

Kaya Genç, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 10-13

Index’s Turkish contributing editor discusses threats against professors that refuse to stick to the syllabus in Turkish universities

Universities under fire in Ukraine’s war by Tatyana Malyarenko

Tatyana Malyarenko, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 14-17

Academic’s jobs are under threat in Ukraine, Tatyana Malarenko discusses how many academics are being hauled in front of special committees and accused of terrorist activity

Industrious academics by Michael Foley

Michael Foley, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 18-19

Lecturer Michael Foley on the commercial pressures being applied to universities in Ireland

Stifling freedom: One hundred years of attacks on US academic freedom by Mark Frary

Mark Frary, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 20-25

Mark Frary takes us through one hundred years of attacks on freedom of expression in US universities

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson

Martin Rowson, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 26-27

Cartoonist Martin Rowson’s regular Index illustration looks at students being gagged at graduation

Ideas under review by Suhrith Parthasarathy

Suhrith Parthasarathy, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 28-30

In India, the autonomy of universities is being challenged by Prime Minister Narendra Modi amidst growing concerns of censorship

Girls standing up for education by Natumanya Sarah, Ijeoma Idika-Chima, and Sajiha Batool

Natumanya Sarah, Ijeoma Idika-Chima, and Sajiha Batool, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 31-33

Three female students from Uganda, Nigeria and Pakistan discuss their experiences of their own education systems

Open-door policy? by Thomas Docherty

Thomas Docherty, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 34-39

Government suppression of UK universities is becoming more and more of an issue, reports Thomas Docherty. Includes the students view by the editor of The Cambridge Tab Sarah Ivers.

Mexican stand-off by Duncan Tucker

Duncan Tucker, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 40-43

Journalist Duncan Tucker lays out the battle for academic freedom in Mexico, where death threats, harassment and beatings are commonplace in universities

Return of the Red Guards by Jemimah Steinfeld

Jemimah Steinfeld, June 2015; vol. 44, 2: pp. 44-49

Index’s contributing editor in China Jemimah Steinfeld reports from China where a targeted campaign against anyone who criticises the ruling party has recently moved to universities

The reading list for threats to academic freedom can be found here

14 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015, Zimbabwe

Zambezi News cast, pictured left to right – Michael Kudakwashe, Samm Farai Monro, Chipo Chikara and Tongai Makawa

The Zimbabwean Minister of Impending Projects proudly stands in front of a mine that he has christened Mine Mine. “Because,” he says, “it’s mine. And because a diamond mine is a minister’s best friend.” This corrupt politician who has never completed a single programme in his department, is a fictional character on Zambezi News, a satirical show I helped create, with fellow activist Outspoken.

Zambezi News has become Zimbabwe’s leading satirical programme, reaching millions of viewers across the country and the whole continent. The show is a parody of the state-controlled propaganda machine, the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation, and mimics the station’s sycophancy to the ruling party, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (Zanu PF). Quite frankly, our show started off by fluke. Outspoken and I have a background as spoken word and hip-hop artists and were approached by a friend involved in a local film festival to do a live news skit. When it aired at the festival and was really well received, we knew we were on to something.

We shot the first season in 2011 as a faux news show with three comic newscasters. The show cut between the newsroom and satirical reports from the field and featured a string of outrageous characters. We even did a special episode for the 2013 elections where our newscaster, Mandape Mandape, showed how easy it is to vote – unless you are young, urban and likely to vote for the opposition. We publicised the show around the country using partners ranging from community radio stations to activist groups. We also pushed it heavily on social media and shared the videos on YouTube. Interest was so great we then produced 10,000 DVDs, which were requested in more than 100 different towns and villages in Zimbabwe. Since then we have shot two more seasons. The show has been viewed by six million Zimbabweans, and we have been invited to do live shows in Sweden, South Africa, Swaziland and the USA.

The fact that there is thriving satire in Zimbabwe and that we, as the cheeky cast of Zambezi News, are still alive confuses a lot of people. Most TV and radio in Zimbabwe is controlled by the state or cronies of the ruling party, so the public has a growing appetite for comedy and satire that present an alternative voice. People like to laugh and think about our crazy situation at the same time.

“Political satire has provided comic relief to many Zimbabweans, but, above all, it has been an innovative way of speaking truth to power,” said political commentator Takura Zhangazha. “Zambezi News is key in carrying on this tradition especially across various media spectrums and between generations.” The fact that we’re still alive? Well, I guess that’s down to luck and the fact that we hide in plain sight.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

However, being a leading satire show and poking fun at the powerful, comes with risks: one of our main actors in Zambezi News has been threatened by people we suspect are state security agents. The actor was approached after we launched our first season in 2012. He was threatened for working on an “anti-government, regime-change agenda” and told that he would be “dealt with”. Our content is blacklisted on state-controlled radio and TV, while we often get attacked by Zanu PF-aligned bloggers who write that we produce “anti-government propaganda”. Earlier this year, as we prepared to launch our third season, the police called up to ask if we had “police clearance” to do so. We also get harassed by the officials from the censorship board and the Central Intelligence Organisation who ask us: “Do you have accreditation and clearance to do this?” I guess this means that they are watching our show, so half our job is done.

We are not alone. Other online satirical shows are emerging, including PO Box, The Comic King Show and LYLO, to name but a few. PO Box has been a viral success in Zimbabwe with its weekly five-minute skits posted on Facebook with the skits getting 20,000 views in two days. The show deals with the country’s social and economic issues and has the cast playing everything from corrupt politicians to victims of xenophobic violence in South Africa. “Comedy and satire depict society’s stance and are the voice of the ordinary people to the elite,” said PO Box creator Luckie Aaroni.

Many outsiders wouldn’t expect to discover Zimbabweans poking fun at the powerful, or mocking the president and his wife, an act that was taboo until recently. “It’s a reflection of the times,” said leading comedian and comedy promoter, Simba The Comic King. “Things are hard, so people might as well laugh about them. That’s their form of protest.” There are also standup shows in the main cities of Harare and Bulawayo. Bulawayo’s gritty Umakhelisa Comedy Club regularly features the city’s top comedians, who joke about the tough social and economic realities that are modern Zimbabwe. Harare’s two leading monthly comedy events, the Bang Bang Comedy Club and Simuka Comedy, often attract capacity crowds to their hard-hitting shows.

Stand-up comedy emerged in Zimbabwe in the 1990s but today has grown into something more daring, where comedians are continually pushing boundaries. However, the authorities don’t always think the jokes should be shared with the public. “A couple of times I have been approached by presumed state security agents who have told me that certain jokes are funny, but get them out of your set if you want to live till the next show,” said Simba. Such threats are real and common in the country. It’s a recurring joke in Zimbabwe among artists: you have freedom of expression, but not freedom after expression.

Despite these trends, Zimbabwe is not an easy place to perform. The state has basically used a carrot-and-stick approach with artists. The carrot is the 75 per cent local-content policy on all state-controlled radio and TV, introduced in April 2000 by the Zanu PF government. For musicians, this means your songs will get played if you aren’t dissing the government and they will get played even more so if you are praising it. And if you’re known to be obedient, Zanu PF might also book you to play at one of its many galas, where taxpayers’ money is used to enchance the party’s image. The stick approach is more straightforward: critical artists get no state support, won’t have their songs played on radio and TV, and are likely to be harassed and threatened.

Artists such as comic character Dr Zobha get airplay on state-controlled radio as they are seen as obedient and toeing the party line. Whereas Zimbabwean music legend Thomas Mapfumo, a national hero for his role in the liberation struggle, was hounded out of the country in 2001 after releasing music critical of Zanu PF. Mapfumo now lives in self-imposed exile in the USA.

With more and more young people online in Zimbabwe sharing videos and content on Facebook and WhatsApp, we now have more and more alternative means of disseminating our content. And considering our politicians aren’t going to stop being clowns anytime soon, we definitely won’t be running out of things to say. So we’ll keep striving to build a new country. One joke at a time.

© Samm Farai Monro

This article is part of the culture section of a special issue of Index on Censorship magazine on academic freedom, featuring contributions from the US, Ukraine, Belarus, Mexico, India, Turkey and Ireland. Subscribe to read the full report, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

This article is part of the culture section of a special issue of Index on Censorship magazine on academic freedom, featuring contributions from the US, Ukraine, Belarus, Mexico, India, Turkey and Ireland. Subscribe to read the full report, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]