9 Jul 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

“Impunity is a great threat to press freedom in Russia,” said Melody Patry, Index on Censorship’s Senior Advocacy Officer. “Failing to use appropriate measures to investigate the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev is not only a denial of justice, it sends the tacit message that you can get away with killing journalists. When perpetrators are not held to account, it encourages further violence towards media professionals.”

Statement

On the 2nd anniversary of the murder of independent Russian journalist, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev, we, the undersigned organisations, call for the investigation into his case to be urgently raised to the federal level.

Akhmednabiyev, deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, was shot dead on 9 July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. He had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

Two years after his killing, neither the perpetrators nor instigators have been brought to justice. The investigation, led by the local Dagestani Investigative Committee, has been repeatedly suspended for long periods over the last year and half, with little apparent progress being made.

Prior to his murder, Akhmednabiyev was subject to numerous death threats including an assassination attempt in January 2013, the circumstances of which mirrored his eventual murder. Dagestani police wrongly logged the assassination attempt as property damage, and only reclassified it after the journalist’s death, demonstrating a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection.

Russia’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the state’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey). Furthermore, at a United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014, member States, including Russia, adopted a resolution (A/HRC/27/L.7) on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

Russia must act on its human rights commitments and address the lack of progress in Akhmednabiyev’s case by removing it from the hands of local investigators, and prioritising it at a federal level. More needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation.

On 2 November 2014, 31 non-governmental organisations from Russia, across Europe as well as international, wrote to Aleksandr Bastrykin calling upon him as the Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case from the regional level to the federal level, in order to ensure an impartial, independent and effective investigation. Specifically, the letter requested that he appoint the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee to continue the investigation.

To date, there has been no official response to this appeal. The Federal Investigative Committee’s public inactivity on this case contradicts a promise made by President Putin in October 2014, to draw investigators’ attention to the cases of murdered journalists in Dagestan.

As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such inaction sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

We urge the Federal Investigation Committee to remedy this situation by expediting Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Federal level as a matter of urgency. This would demonstrate a clear willingness, by the Russian authorities, to investigate this crime in a thorough, impartial and effective manner.

Supported by

ARTICLE 19

Albanian Media Institute

Analytical Center for Interethnic Cooperation and Consultations (Georgia)

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

The Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House

Belorussian Helsinki Committee

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Crude Accountability

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

The Human Rights Center of Azerbaijan

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

Kharkiv Regional Foundation -Public Alternative (Ukraine)

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN International

Promo LEX Moldova

Public Verdict (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

Заявление по-русски

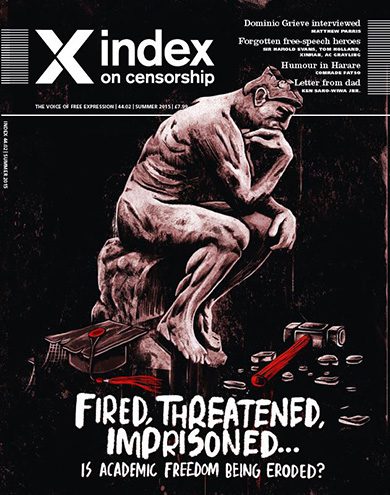

26 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Letters, Magazine, News and features, Turkey Letters, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

With threats ranging from “no-platforming” controversial speakers, to governments trying to suppress critical voices, and corporate controls on research funding, academics and writers from across the world have signed Index on Censorship’s open letter on why academic freedom needs urgent protection.

Academic freedom is the theme of a special report in the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine, featuring a series of case studies and research, including stories of how setting an exam question in Turkey led to death threats for one professor, to lecturers in Ukraine having to prove their patriotism to a committee, and state forces storming universities in Mexico. It also looks at how fears of offence and extremism are being used to shut down debate in the UK and United States, with conferences being cancelled and “trigger warnings” proposed to flag potentially offensive content.

Signatories on the open letter include authors AC Grayling, Monica Ali, Kamila Shamsie and Julian Baggini; Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey), Sarah Churchwell (University of East Anglia), Thomas Docherty (University of Warwick), Michael Foley (Dublin Institute of Technology), Richard Sambrook (Cardiff University), Alan M. Dershowitz (Harvard Law School), Donald Downs (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Professor Glenn Reynolds (University of Tennessee), Adam Habib (vice chancellor, University of the Witwatersrand), Max Price (vice chancellor of University of Cape Town), Jean-Paul Marthoz (Université Catholique de Louvain), Esra Arsan (Istanbul Bilgi University) and Rossana Reguillo (ITESO University, Mexico).

The letter states:

We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world from Turkey to China to the USA. In Mexico academics face death threats, in Turkey they are being threatened for teaching areas of research that the government doesn’t agree with. We feel strongly that the freedom to study, research and debate issues from different perspectives is vital to growing the world’s knowledge and to our better understanding. Throughout history, the world’s universities have been places where people push the boundaries of knowledge, find out more, and make new discoveries. Without the freedom to study, research and teach, the world would be a poorer place. Not only would fewer discoveries be made, but we will lose understanding of our history, and our modern world. Academic freedom needs to be defended from government, commercial and religious pressure.

Index will also be hosting a debate in London, Silenced on Campus, on 1 July, with panellists including journalist Julie Bindel, Nicola Dandridge of Universities UK, and Greg Lukianoff, president and CEO of Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, US.

To attend for free, register here.

If you would like to add your name to the open letter, email [email protected]

A full list of signatories:

Professor Mike Adams, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, USA

Monica Ali, author

Lyell Asher, associate professor, Lewis & Clark College, USA

Professor Jim Al-Khalili OBE, University of Surrey, UK

Esra Arsan, associate professor, Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey

Julian Baggini, author

Professor Mark Bauerlein, Emory University, USA

David S. Bernstein, publisher, USA

Robert Bionaz, associate professor, Chicago State University, USA

Susan Blackmore, visiting professor, University of Plymouth, UK

Professor Jan Blits, professor emeritus, University of Delaware, USA

Professor Enikö Bollobás, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Professor Roberto Briceño-León, LACSO, Caracas, Venezuela

Simon Callow, actor

Professor Sarah Churchwell, University of East Anglia, UK

Professor Martin Conboy, University of Sheffield, UK

Professor Thomas Cushman, Wellesley College, USA

Professor Antoon De Baets, University of Groningen, Holland

Professor Alan M Dershowitz, Harvard Law School, USA

Rick Doblin, Association for Psychedelic Studies, USA

Professor Thomas Docherty, University of Warwick, UK

Professor Donald Downs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

Professor Alice Dreger, Northwestern University, USA

Michael Foley, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Professor Tadhg Foley, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Nick Foster, programme director, University of Leicester, UK

Professor Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

AC Grayling, author

Professor Randi Gressgård, University of Bergen, Norway

Professor Adam Habib, vice-chancellor, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Professor Gerard Harbison, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Adam Hart Davis, author and academic, UK

Professor Jonathan Haidt, NYU-Stern School of Business, USA

John Earl Haynes, retired political historian, Washington, USA

Professor Gary Holden, New York University, USA

Professor Mickey Huff, Diablo Valley College, USA

Professor David G. Hoopes, California State University, USA

Philo Ikonya, poet

James Ivers, lecturer, Eastern Michigan University, USA

Rachael Jolley, editor, Index on Censorship

Lee Jones, senior lecturer, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Stephen Kershnar, distinguished teaching professor, State University of New York, Fredonia, USA

Professor Laura Kipnis, Northwestern University, USA

Ian Kilroy, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Val Larsen, associate professor, James Madison University, USA

Wendy Law-Yone, author

Professor Michel Levi, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Professor John Wesley Lowery, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA

Greg Lukianoff, president and chief executive, Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), USA

Professor Tetyana Malyarenko, Donetsk State Management University, Ukraine

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director, Sage

Charlie Martin, editor PJ Media, UK

Jean-Paul Marthoz, senior lecturer, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium

Professor Alan Maryon-Davis, King’s College London, UK

John McAdams, associate professor, Marquette University, USA

Timothy McGuire, associate professor, Sam Houston State University, USA

Professor Tim McGettigan, Colorado State University, USA

Professor Lucia Melgar, professor in literature and gender studies, Mexico

Helmuth A. Niederle, writer and translator, Germany

Professor Michael G. Noll, Valdosta State University, USA

Undule Mwakasungula, human rights defender, Malawi

Maureen O’Connor, lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Professor Niamh O’Sullivan, curator of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, and Quinnipiac University, Connecticut, USA

Behlül Özkan, associate professor, Marmara University, Turkey

Suhrith Parthasarathy, journalist, India

Professor Julian Petley, Brunel University, UK

Jammie Price, writer and former professor, Appalachian State University, USA

Max Price, vice-chancellor, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Clive Priddle, publisher, Public Affairs

Professor Rossana Reguillo, ITESO University, Mexico

Professor Glenn Reynolds, University of Tennessee College of Law, USA

Professor Matthew Rimmer, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Professor Paul H. Rubin, Emory University, USA

Andrew Sabl, visiting professor, Yale University, USA

Alain Saint-Saëns, director,Universidad Del Norte, Paraguay

Professor Richard Sambrook, Cardiff University, UK

Luís António Santos, University of Minho, Portugal

Professor Francis Schmidt, Bergen Community College, USA

Albert Schram, vice chancellor/CEO, Papua New Guinea University of Technology

Victoria H F Scott, independent scholar, Canada

Kamila Shamsie, author

Harvey Silverglate, lawyer and writer, Massachusetts, USA

William Sjostrom, director and senior lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Suzanne Sisley, University of Arizona College of Medicine, USA

Chip Stewart, associate dean of the Bob Schieffer College of Communication, Texas Christian University, USA

Professor Nadine Strossen, New York Law School, USA

Professor Dawn Tawwater, Austin Community College, USA

Serhat Tanyolacar, visiting assistant professor, University of Iowa, USA

Professor John Tooby, University of California, USA

Meena Vari, Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore, India

Professor Leland Van den Daele, California Institute of Integral Studies, USA

Professor Eugene Volokh, UCLA School of Law, USA

Catherine Walsh, poet and teacher, Ireland

Christie Watson, author

Ray Wilson, author

Professor James Winter, University of Windsor, Canada

22 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Counter Terrorism, Magazine, United Kingdom, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

Students at a protest in Manchester. Photo: Alamy/ M Itani

The realisation of academic freedom typically depends on controversy: it voices dissent. Linked to free speech, it is marked primarily by critique, speaking against – even offending against – prevailing or accepted norms. If it is to be heard, to make a substantial difference, such speech cannot be entirely divorced from rules or law. Yet legitimate rule – law – is itself established through talk, discussion and debate. Academic freedom seeks a new linguistic bond by engaging with or even producing a free assembly of mutually linked speakers. To curb such freedom, you delegitimise certain speakers or forms of speech; and the easiest way to do this is to isolate a speaker from an audience and to isolate members of an audience from each other. Silence the speaker; divide and rule the audience. When that seems extreme, work surreptitiously: attack not what is said but its potentially upsetting or offensive “tone”. Such inhibitions on speech increasingly chill conditions on campus.

Academic freedom is typically enshrined in university statutes, a typical formulation being that “academic staff have freedom within the law to question and test received wisdom, and to put forward new ideas and controversial or unpopular opinions, without placing themselves in jeopardy of losing their jobs or privileges” – as the statutes of the University of Warwick, where I work, have it. Yet academic freedom is now being fundamentally weakened and qualified by legislation, with which universities must comply.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, speaking in Munich on 5 February 2011, said: “We must stop these groups [terrorists] from reaching people in publicly funded institutions like universities.” This was followed by a UK government report on tackling extremism, released ahead of the recent election, which said: “Universities must take seriously their responsibility to deny extremist speakers a platform.” It was suggested that “Prevent co-ordinators” could “give universities access to the information they need to make informed decisions” about who they allowed to speak on campuses. Ahead of May’s UK election university events had already been changed or cancelled. And immediately after the election, the government signalled its intention to focus further on the extremism agenda. In endorsing this approach, university vice-chancellors have acquiesced in a too-intimate identification of the interests of the search for better argument with whatever is stated as government policy. The expectation is that academics will in turn give up the autonomy required to criticise that policy or those who now manage it on government’s behalf in our institutions.

Governments worldwide increasingly assert the legal power to curtail the free speech and freedom of assembly that is axiomatic to the existence of academic freedom. This endangers democracy itself, what John Stuart Mill called “governance by discussion”. The economist Amartya Sen, for example, has recently resigned from his position as chancellor of Nalanda University in India because of what he saw as “political interference in academic matters” whereby “academic governance in India remains … deeply vulnerable to the opinions of the ruling government”. (See our report from India in our academic freedom special issue.) This is notable because it is one extremely rare instance of a university leader taking a stand against government interference in the autonomous governance of universities, autonomy that is crucial to the exercise of speaking freely without jeopardy.

Academic freedom, and the possibilities it offers for democratic assembly in society at large, now operates under the sign of terror. This has empowered governments to proscribe not just terrorist acts but also talk about terror; and governments have identified universities as a primary location for such talk. Clearly closing down a university would be a step too far; but just as effective is to inhibit its operation as the free assembly of dissenting voices. We have recently wit- nessed a tendency to quarantine individuals whose voices don’t comply with governance/ government norms. Psychology professor Ian Parker was suspended by Manchester Metropolitan University and isolated from his students in 2012, charged with “serious misconduct” for sending an email that questioned management. In 2014, I myself was suspended by the University of Warwick, barred from having any contact with colleagues and students, barred from campus, prevented from attending and speaking at a conference on E P Thompson, and more. Why? I was accused of undermining a colleague and asking critical questions of my superiors, the answers to which threatened their supposedly unquestionable authority. None of these charges were later upheld at a university tribunal.

More insidious is the recourse to “courtesy” as a means of preventing some speech from enjoying legitimacy and an audience. Several UK institutions have recently issued “tone of voice” guidelines governing publications. The University of Manchester, for example, says that “tone of voice is the way we express our brand personality in writing”; Plymouth University argues that “by putting the message in the hands of the communicator, it establishes a democracy of words, and opens up new creative possibilities”. These statements should be read in conjunction with the advice given by employment lawyer David Browne, of SGH Martineau (a UK law firm with many university clients). In a blogpost written in July 2014, he argued that high-performing academics with “outspoken opinions”, might damage their university’s brand and in it made comparisons between having strong opinions and the behaviour of footballer Luis Suárez in biting another player during the 2014 World Cup. The blog was later updated to add that its critique only applied to opinions that “fall outside the lawful exercise of academic freedom or freedom of speech more widely”, according to the THES (formerly the Times Higher Education Supplement). Conformity to the brand is now also conformity to a specific tone of voice; and the tone in question is one of supine compliance with ideological norms.

This is increasingly how controversial opinion is managed. If one speaks in a tone that stands out from the brand – if one is independent of government at all – then, by definition, one is in danger of bringing the branded university into disrepute. Worse, such criticism is treated as if it were akin to terrorism-by-voice.

Nothing is more important now than the reassertion of academic freedom as a celebration of diversity of tone, and the attendant possibility of giving offence; otherwise, we become bland magnolia wallpaper blending in with whatever the vested interests in our institutions and our governments call truth.

This vested interest – especially that of the privileged or those in power – now parades as victim, hurt by criticism, which it calls of- fensive disloyalty. What is at issue, however, is not courtesy; rather what is required of us is courtship. As in feudal times, we are legitimised through the patronage of the obsequium that is owed to the overlords in traditional societies.

Academic freedom must reassert itself in the face of this. The real test is not whether we can all agree that some acts, like terrorism, are “barbaric” in their violence; rather, it is whether we can entertain and be hospitable to the voice of the foreigner, of she who thinks – and speaks – differently, and who, in that difference, offers the possibility of making a new audience, new knowledge and, indeed, a new and democratic society, governed by free discussion.

© Thomas Docherty

Thomas Docherty is professor of English and of comparative literature at the University of Warwick in the UK.

This article is part of a special issue of Index on Censorship magazine on academic freedom, featuring contributions from the US, Ukraine, Belarus, Mexico, India, Turkey and Ireland. Subscribe to read the full report, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

11 Jun 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Russia

Pope Francis met with Russian President Vladimir Putin (Photos: Pope Francis: Korean Culture and Information Service/Wikimedia Commons; Vladimir Putin: Kremlin.ru/Wikimedia Commons)

What might have happened when the leader of the world’s largest state met the leader of the world’s smallest?

Francis: Welcome to the Vatican, Vladimir. I hope you are not put off by my incredibly humble surroundings, here in my own humble city state. I am very humble, you know.

Vladimir: Yes, so your aides reminded me, several times. It is very important for men as important as ourselves to stay humble, I believe. We would not want to, as they say, “lose the run of ourselves”. Tell me, dear humble priest: I hear you are a communist now?

Francis (laughing, filled with divine light and humility): Haha! Not quite, comrade. The only redistribution I’m interested in is the redistribution of Christ’s love. The only means of production I want to seize control of are the means of production of compassion in men’s hearts. The only permanent revol…

Vlad: Right, yes, I think I get it. So, the whole “praying for the conversion of Russia” thing: that’s not a thing any more?

Frank: Oh that? Lord no. Thing of the past. If anything, we’re praying for the rest of the world to be more like Russia. Look at the rest of the world: secular, godless, decadent, lacking a certain…what’s the word I’m looking for?

Vlad: Humility?

Frank: Yeah, that’s the one. Lacking humility. But Russia. In Russia, the church is still number one. Admittedly, the wrong church, but, well, who am I to be picky?

Vlad: Good to know. So, where did the communist thing come from?

Frank: Ah, the Americans. You know how they are.

Vlad: I see. So you have been defamed by the Yanqui too? I have had my trouble with them. They even claimed I invaded Ukraine. HAHAHA!

Frank (nervously, humbly): HAHAHAHAHAH (hmm). Daft, of course. I mean, you didn’t, did you?

Vlad: Of course not! Why would I do that?

Frank: Well, they might have insulted your mother. In which case you’d have every right, as I outlined in my pamphlet: “Ego In Gutture Ferrum, Punk”

Vlad: Um, right.

Frank: It’s totally theologically sound. As Jesus himself said: “I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, punch them in the throat.”

Vlad (under breath): Catholics are weird

Frank: You talking about my mother?

Vlad: No! No! Lord no. Holy Father, if I may call you that…

Frank: I humbly accept the title

Vlad: Holy Father, it is true, as you said, that if someone insults someone’s mother, they should expect a punch?

Fran: It’s not just me saying that. Jesus says it!

Vlad: I’m almost certain he doesn’t, but hey, you’re the Pope.

Frank: I am, you know.

Vlad: Anyway, what does one do when someone, say, doesn’t insult your mother, but insults you, and you can’t punch them in the throat because they’re women and apparently you’re not supposed to do that anymore?

Frank: Not following.

Vlad: That, group: those awful people whose name I can’t really say in front of a priest.

Frank: Ah! The Pussy Riots band!

Vlad: Well, I was thinking “the feminists”, but yes, them. Was it OK to send them to the Gulag?

Frank: I’m not really sure I’m in a position to comment here. The organisation of which I humbly find myself head doesn’t have…we don’t have a great track record on the whole locking-up-unruly-girls thing.

Vlad: Oh yes, that. You’ve stopped doing that, right?

Frank: Pretty much. How about you? Your lot were pretty keen on the whole packing-em-off thing.

Vlad: Ha, yes. I’ll square with you, Frank. Can I call you Frank?

Frank: No.

Vlad: Ah. Ok. Awks. Er, I’ll square with you, Holy Father: the gulag thing’s a hard habit to break. You know, you’ve got the rigged courts, the fantasy charges… but most of all, I mean…it’s heritage, isn’t it? Tradition.

Frank: Tradition!

Vlad: Tradition, you know…(sings) “Il Papa. Il Papa, Tradition!”

Frank: Stop that.

Vlad: Sorry, can’t help myself. Love that show.

Frank: Yes, we all do. But, y’know, not here. Vatican and all that. Don’t have a great record on those people either.

Vlad. Who? Musical theatre people?

Frank: Well, I was going to say the…but yes, the musical theatre people.

Vlad: We too have our trouble with the musical theatre people. Must they be so theatrical? In front of the children? I mean, what if everyone was theatrical? What then? Everyone would be putting the show on right here and no one would be making babies.

Frank: So true.

Vlad: I mean, it’s not like I’m obsessed or anything. I’m not that bothered by them, honest. Hell, I’ve even been to a few musicals.

Frank: Let he among us who hasn’t been touched by musical theatre throw the first punch.

Vlad: Um, right.

Frank: Ha! I see even you are a bit put out by the constant talk of punching. But I was a bouncer in Buenos Aires. And you know what we say in Argentina? “You can’t spell ‘Bad Boy’ without BA!” Ha!

Vlad: Good one. Back in Leningrad we used to say “You can’t spell ‘Please! Stop! I’ll confess to anything!’ without ‘KGB’”

Frank: ?

Vlad: It works in Russian. Different alphabet.

Frank: Of course.

Vlad: Anyway, where was I? Yes, the musical theatre people. I mean, all very well in it’s place…

Frank: New York?

Vlad: EXACTLY. But why bring it to Russia?

Frank: Exactly. Sometimes its like they think they should have their own stage in their own building in every parish in the world where they can get all dressed up and put on their strange little performances, and we’re all supposed to worship them for it. Such arrogance, a humble man such as I cannot countenance.

Vlad: Quite.

Frank: I’m glad we can agree on so much. Tell me, you seem like a good, God-fearing, throat-punching man…

Vlad: Why thank you

Frank: Why is it you get such bad press?

Vlad: Well, I’ve got a plan to deal with that.

Frank: Really? Me too. I noticed the guy before me came across as a bit austere, so I decided to say all the same things he said, but in a much more liberal-sounding way. The media loves it. So, what’s your plan for dealing with journalists?

Vlad: Kill them.

Frank: Oh! Ah well, suffer little children to come unto me, as the Lord said.

Vlad: I’m pretty sure that doesn’t mean what you think it means.

Frank: Vlad, you’re a pal, but who’s the one with a direct line to God here?

Vlad: Good question, comrade. Good question.

(Lunch is served).

This column was posted on 12 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org