15 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Beyond its near neighbourhood, the EU works to promote freedom of expression in the wider world. To promote freedom of expression and other human rights, the EU has 30 ongoing human rights dialogues with supranational bodies, but also large economic powers such as China.

The EU and freedom of expression in China

The focus of the EU’s relationship with China has been primarily on economic development and trade cooperation. Within China some commentators believe that the tough public noises made by the institutions of the EU to the Chinese government raising concerns over human rights violations are a cynical ploy so that EU nations can continue to put financial interests first as they invest and develop trade with the country. It is certainly the case that the member states place different levels of importance on human rights in their bilateral relationships with China than they do in their relations with Italy, Portugal, Romania and Latvia. With China, member states are often slow to push the importance of human rights in their dialogue with the country. The institutions of the European Union, on the other hand, have formalised a human rights dialogue with China, albeit with little in the way of tangible results.

The EU has a Strategic Partnership with China. This partnership includes a political dialogue on human rights and freedom of the media on a reciprocal basis.[1] It is difficult to see how effective this dialogue is and whether in its present form it should continue. The EU-China human rights dialogue, now 14 years old, has delivered no tangible results.The EU-China Country Strategic Paper (CSP) 2007-2013 on the European Commission’s strategy, budget and priorities for spending aid in China only refers broadly to “human rights”. Neither human rights nor access to freedom of expression are EU priorities in the latest Multiannual Indicative Programme and no money is allocated to programmes to promote freedom of expression in China. The CSP also contains concerning statements such as the following:

“Despite these restrictions [to human rights], most people in China now enjoy greater freedom than at any other time in the past century, and their opportunities in society have increased in many ways.”[2]

Even though the dialogues have not been effective, the institutions of the EU have become more vocal on human rights violations in China in recent years. For instance, it included human rights defenders, including Ai Weiwei, at the EU Nobel Prize event in Beijing. The Chinese foreign ministry responded by throwing an early New Year’s banquet the same evening to reduce the number of attendees to the EU event. When Ai Weiwei was arrested in 2011, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton issued a statement in which she expressed her concerns at the deterioration of the human rights situation in China and called for the unconditional release of all political prisoners detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression.[3] The European Parliament has also recently been vocal in supporting human rights in China. In December 2012, it adopted a resolution in which MEPs denounced the repression of “the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, press freedom and the right to join a trade union” in China. They criticised new laws that facilitate “the control and censorship of the internet by Chinese authorities”, concluding that “there is therefore no longer any real limit on censorship or persecution”. Broadly, within human rights groups there are concerns that the situation regarding human rights in China is less on the agenda at international bodies such as the Human Rights Council[4] than it should be for a country with nearly 20% of the world’s population, feeding a perception that China seems “untouchable”. In a report on China and the International Human Rights System, Chatham House quotes a senior European diplomat in Geneva, who argues “no one would dare” table a resolution on China at the HRC with another diplomat, adding the Chinese government has “managed to dissuade states from action – now people don’t even raise it”. A small number of diplomats have expressed the view that more should be done to increase the focus on China in the Council, especially given the perceived ineffectiveness of the bilateral human rights dialogues. While EU member states have shied away from direct condemnation of China, they have raised freedom of expression abuses during HRC General Debates.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy and human rights dialogues

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is the agreed foreign policy of the European Union. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 allowed the EU to develop this policy, which is mandated through Article 21 of the Treaty of the European Union to protect the security of the EU, promote peace, international security and co-operation and to consolidate democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedom. Unlike most EU policies, the CFSP is subject to unanimous consensus, with majority voting only applying to the implementation of policies already agreed by all member states. As member states still value their own independent foreign policies, the CFSP remains relatively weak, and so a policy that effectively and unanimously protects and promotes rights is at best still a work in progress. The policies that are agreed as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy therefore be useful in protecting and defending human rights if implemented with support. There are two key parts of the CFSP strategy to promote freedom of expression, the External Action Service guidelines on freedom of expression and the human rights dialogues. The latter has been of variable effectiveness, and so civil society has higher hopes for the effectiveness of the former.

The External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines

As part of its 2012 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU is working on new guidelines for online and offline freedom of expression, due by the end of 2013. These guidelines could provide the basis for more active external policies and perhaps encourage a more strategic approach to the promotion of human rights in light of the criticism made of the human rights dialogues.

The guidelines will be of particular use when the EU makes human rights impact assessments of third countries and in determining conditionality on trade and aid with non-EU states. A draft of the guidelines has been published, but as these guidelines will be a Common Foreign and Security Policy document, there will be no full and open consultation for civil society to comment on the draft. This is unfortunate and somewhat ironic given the guidelines’ focus on free expression. The Council should open this process to wider debate and discussion.

The draft guidelines place too much emphasis on the rights of the media and not enough emphasis on the role of ordinary citizens and their ability to exercise the right to free speech. It is important the guidelines deal with a number of pressing international threats to freedom of expression, including state surveillance, the impact of criminal defamation, restrictions on the registration of associations and public protest and impunity against human right defenders. Although externally facing, the freedom of expression guidelines may also be useful in indirectly establishing benchmarks for internal EU policies. It would clearly undermine the impact of the guidelines on third parties if the domestic policies of EU member states contradict the EU’s external guidelines.

Human rights dialogues

Another one of the key processes for the EU to raise concerns over states’ infringement of the right to freedom of expression as part of the CFSP are the human rights dialogues. The guidelines on the dialogues make explicit reference to the promotion of freedom of expression. The EU runs 30 human rights dialogues across the globe, with the key dialogues taking place in China (as above), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Belarus. It also has a dialogues with the African Union, all enlargement candidate countries (Croatia, the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia and Turkey), as well as consultations with Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Russia. The dialogue with Iran was suspended in 2006. Beyond this, there are also “local dialogues” at a lower level, with the Heads of EU missions, with Cambodia, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Israel, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Vietnam. In November 2008, the Council decided to initiate and enhance the EU human rights dialogues with a number of Latin American countries.

It is argued that because too many of the dialogues are held behind closed doors, with little civil society participation with only low-level EU officials, it has allowed the dialogues to lose their importance as a tool. Others contend that the dialogues allow the leaders of EU member states and Commissioners to silo human rights solely into the dialogues, giving them the opportunity to engage with authoritarian regimes on trade without raising specific human rights objections.

While in China and Central Asia the EU’s human rights dialogues have had little impact, elsewhere the dialogues are more welcome. The EU and Brazil established a Strategic Partnership in 2007. Within this framework, a Joint Action Plan (JAP) covering the period 2012-2014 was endorsed by the EU and Brazil, in which they both committed to “promoting human rights and democracy and upholding international justice”. To this end, Brazil and the EU hold regular human rights consultations that assess the main challenges concerning respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law; advance human rights and democracy policy priorities and identify and coordinate policy positions on relevant issues in international fora. While at present, freedom of expression has not been prioritised as a key human rights challenge in this dialogue, the dialogues are seen by both partners as of mutual benefit. It is notable that in the EU-Brazil dialogue both partners come to the dialogues with different human rights concerns, but as democracies. With criticism of the effectiveness and openness of the dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states in the promotion of human rights with third countries and assess whether the dialogues can be improved.

[1] It covers both press freedom for the Chinese media in Europe and also press freedom for European media in China.

[2] China Strategy Paper 2007-2013, Annexes, ‘the political situation’, p. 11

[3] “I urge China to release all of those who have been detained for exercising their universally recognised right to freedom of expression.”

[4] Interview with European diplomat, February 2013.

3 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, United States

San Fransisco based Reddit.com made headlines when it allegedly banned climate change deniers from posting on the site.

UK-based freedom of speech advocate Brendan O’Neill, editor of Spiked magazine, claimed it had “shredded its own reputation” in a piece for The Telegraph, while James Delingpole, a right-wing commentator for The Spectator delivered a hot-blooded attack on the policy via Fox News website – “The greenies — and their many useful idiots in the liberal media — are terrified of open debate on climate-change because the real world evidence long ago parted company with their scientifically threadbare theory.”

Reddit is a huge online links directory and lively discussion board, with a reputation for scale, wit, lack of censorship and a strong sense of community. Over eighty million monthly unique visitors, two hundred and sixty million comments to date and a presence in one hundred and eighty countries are some of the stats that led Conde Nast to buy the company a year after it was launched in 2005. Last year, analysts valued it at over $200 million dollars. It’s no Facebook or Twitter in terms of publicity attracted, but it gets more traffic than CNN, and the Guardian.com’s monthly readership could fit into Reddit’s three times over.

It’s the famed lack of censorship that has lead opinion writers on both side of the Atlantic to point out this new policy on climate change denial.

For those who haven’t visited, the site is divided up into sub-reddits–links and discussions, which are classified according to themes, and run by unpaid volunteers.

“TIL,” shorthand for “Today I Learned,” offers obscure trivia and little known facts. “foreignpolicy” offers links and discussion on international relations, defence and diplomacy. “foodforthought” collates links to thought-provoking essays. There are subreddits for jokes, celebrity gossip, memes and funny videos – for agony aunts and video gaming.

In fact, rather than reddit.com having banned climate change skeptics, it’s the moderators of the “/r/science” reddit who have instigated the ban. Run by volunteers, it collects links about new research and scientific articles.

“/r/science is not the beginning or the end of internet discussion”, defends Carl Ellstrom from Sweden – a reddit user, scientist and moderator of the science subreddit. “Users who are banned from /r/science are not banned from reddit, and can discuss their opinions in other subreddits.”

While it’s not the beginning or the end, /r/science still attracts millions of visitors each month. So the decision to ban climate change scepticism is of note.

Typical of their profession–other moderators backed up the decision by citing research–97% of climate scientists agree that man is changing the planet, according to a report from the respected Institute of Physics.

The move principally revolved around aggressive and repeated comments, which a small group of malicious users were posting on every article or piece of research concerned with climate change. Their allegations generally focused on conspiracy theories, didn’t address the article with constructive, focused criticism, were repetitive and, critically, had a disproportionate silencing effect on any discussion.

“These problematic users were not the common ‘internet trolls’ looking to have a little fun upsetting people,” explains Nathan Allen, a PhD chemist with a major chemical company and reddit moderator who wrote for The Guardian.

“These people were true believers, blind to the fact that their arguments were hopelessly flawed, the result of cherry-picked data and conspiratorial thinking. They had no idea that the smart-sounding talking points from their preferred climate blog were, even to a casual climate science observer, plainly wrong. They were completely enamoured by the emotionally charged and rhetoric-based arguments of pundits on talk radio and Fox News.”

Expanding on that last point Allen says the same comparison could be made with the climate change denial lobby in general, and their disproportionate influence on the press.

“Like our commenters, professional climate change deniers have an outsized influence in the media and the public. And like our commenters, their rejection of climate science is not based on an accurate understanding of the science but on political preferences and personality.”

He ends his piece with a deliberate challenge to the editors of the world’s largest websites

“If a half-dozen volunteers can keep a page with more than 4 million users from being a microphone for the antiscientific, is it too much to ask for newspapers to police their own editorial pages as proficiently?”

If Allen’s suggestion was ever to be noticed and accepted by editors–he ramifications for freedom of speech and media censorship would be radical. Editors might be forced to ignore lobbying from certain spheres of belief, or might miss out on important stories.

But UK research published earlier in the year, shows the disproportionate effect on distorting the truth that having a free and open press creates.

On average, Brits think teenage pregnancies are twenty five times higher than official estimates. The public think 31% of the population are immigrants–the reality is closer to ten percent. Welfare benefit fraud is thought to be 34 times higher than it actually is.

All of the misconceptions covered by IPSOS Mori, the polling company that undertook the research, have been central to political party manifestos and been aggressively pushed by their PR companies.

Or that journalists are too readily being made tools of political parties who want to get elected, who want the issues that they care most about continually in the press, hotly discussed and “on the agenda.” Perhaps we, as journalists, need to remain ever vigilant to the briefing of misinformation and our responsibility to the truth.

This article was published on 3 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

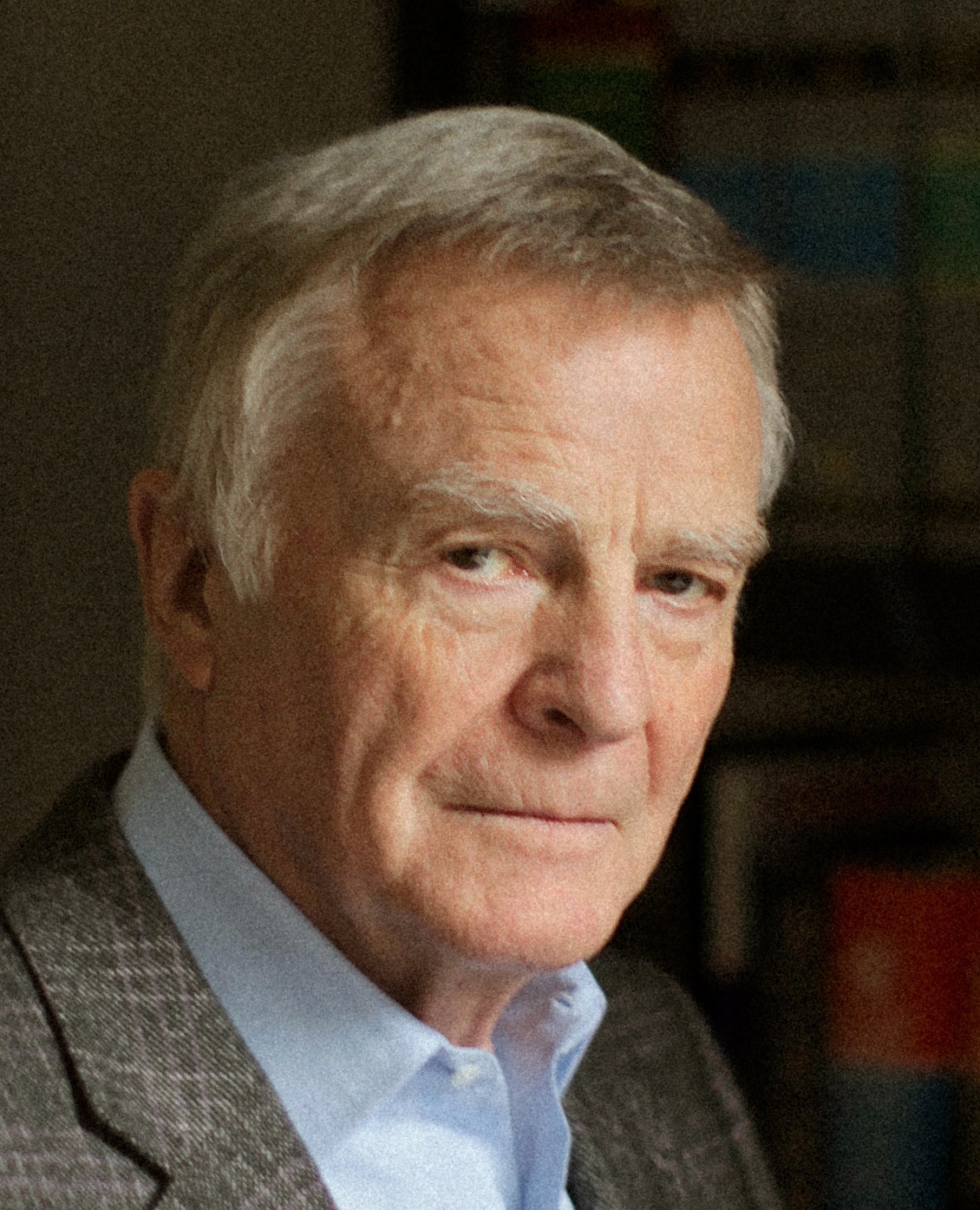

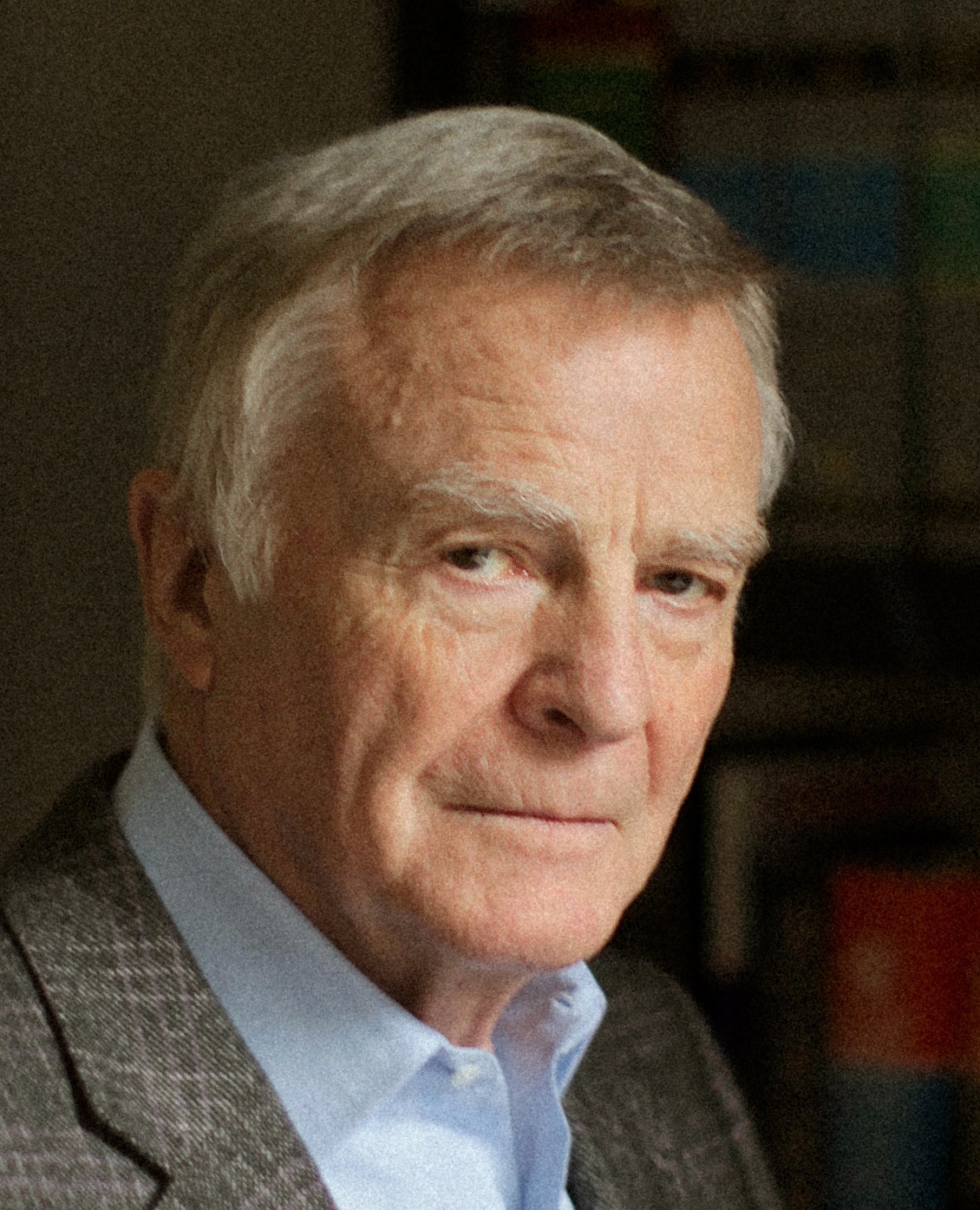

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).

31 Dec 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Greece, News and features, Politics and Society

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

As Greece prepares to take on the presidency of the Council of the European Union on January 1, the country continues to grapple with the free expression fallout from its financial crisis.

The Greek constitution protects freedom of expression in Article 14, a very lengthy provision detailing the rights and restrictions. As set in the first paragraph of Art. 14 “every person may express and propagate his thoughts orally, in writing and through the press in compliance with the laws of the State”.

Aside from domestic legislation, Greece cooperates with a number of international organizations and is a contracting party to treaties related to freedom of expression, civil/political rights and access to information, for instance the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

However, the heavy austerity measures imposed since 2010, after the fiscal agreements between the Greek government and the “troika” (IMF, European Commission, European Central Bank), resulted in serious violations of human rights including freedom of speech. Cuts in government spending forced impoverishment upon large segments of society and came with a heavy price of social exclusion and marginalization.

Reports from various intergovernmental organizations, NGOs and civil society groups are raising alarms about policies followed by the Greek state. Human rights such as free expression, free thought, free movement, right to work, equal treatment, access to decision-making and right to protest are being systematically attacked.

On 16 April 2013, Nils Muižnieks, the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, published a report on human rights issues. Muiznieks urged the Greek government to use all legal instruments, domestic and international, to combat hate speech and racist crime, largely attributed to the rise of the neo-nazi party Golden Dawn.

Government Transparency: call for social justice

Looking at the evidence coming from official institutions and NGOs, the “pillar” of government accountability is characterized by corruption and maladministration.

Although “micro-corruption” is less of a problem, mainly due to economic problems, Greece is still perceived as the most corrupt nation in the European Union. In a total of 177 countries worldwide, Greece ranks 80, although some progress has been made from last year.

According to the 2012 annual report of the Greek Ombudsman, a constitutionally sanctioned independent authority investigating administrative actions regarding personal rights, “the call for social justice is the main feature of people’s complaints, reflecting the existing social fatigue.”

After evaluating the significant increase in the number of complaints, the Ombudsman reported that citizen encounters with the administration have intensified, while the explosive social conditions have lead to greater loss in human rights protection.

Press Freedom: under attack

Greece’s dramatic fall in the ranking of 2013 World Press Freedom Index, is evidence of the oppressive environment journalism is practised. Since 2008, Greece has fallen from 31 place to 84.

In the past three years, mainstream media have been experiencing a significant deterioration in their “watchdog’ role, as a result of the crisis and of long-term weaknesses and practices.

The Greek media market is shaped by media groups owned by magnates, shipowners and big contractors. Having vested interests in profitable industries, these tycoons have been working closely with every regime to ensure their dominance at any cost.

In additiona, the financial crisis has led to closures and severe cutbacks at print and broadcast outlets while hindering effective reporting and quality journalism.

Ιndex on Censorship has thoroughly reported on politically motivated firings or suspensions at both state and private media.

The case of investigative journalist Kostas Vaxevanis is an indicative example of the governments’ approach to press freedom. Vaxevanis was arrested and prosecuted after publishing a list of more than 2,000 suspected tax evaders, the so called “Lagarde list”.

Moreover, Reporters Without Borders, in a special investigation report dating from September 2011, suggested that a crisis of confidence in journalism has resulted to a devaluation process of the profession. RWB highlighted the risks entailed in reporting at street demonstrations and violent clashes with the police: “Working conditions during demonstrations are nowadays rather like in a war zone”.

During the crisis, the need for more investigative reporting led several bloggers and online activists to form independent media collectives.

While mainstream media failed to report on the social struggle, these collectives managed to report complaints and publicise dissent. But not without a cost. On April 11 2013, Indymedia, an anti-authoritarian internet collective, had its plug pulled by the government for reporting on police brutality cases and exposing the deeds of neo-fascist Golden Dawn.

In late September 2012, the case of Elder Pastitsios showed that online satire cannot be tolerated. A 27-year-old man, who published a Facebook post mocking a well known Orthodox monk, was arrested on charges of malicious blasphemy and religious insult.

It’s perhaps the first time an internet company disclosed information to the Greek authorities in order to identify an individual accused of an alleged offense relating to religious satire.

LGBTI: Living in a conservative society

Several incidents of state censorship and social discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation illustrate the mentality of an oppressive society.

According to IGAL’s Annual Review Greece ranks 25 among 49 European countries. A wave of violence has been recorded against LGBTI activists and supporters, from conservatives, extremists and supporters of the Golden Dawn party.

In 2013, (ex) Greek State television ERT decided to censor a kissing scene between men from the TV drama Downton Abbey. Following the reactions from the LGBTI community and the intervention of Greek Ombudsman, the broadcaster issued a communiqué apologizing for the “unfortunate decision”.

It is worth noting that Greece has been found violating the European Convention of Human Rights, regarding its decision to exclude same sex couples from the institution of civil partnership. Although the government plans to extend the legislation to same sex couples, there are continuing pressures from conservatives as well as from the Church.

The impact of orthodox religion to Greek society is so strong that sometimes it can be an obstacle in the perception of artistic attempts. Recently, it lead to the intimidation and persecution of a theatrical play whereby homosexuality was used as a narrative technique.

Migrants, asylum seekers, Roma: the most vulnerable

Human rights abuses against immigrants, asylum seekers and other minorities in Greece have escalated dramatically. The approach of the Greek government — together with the racist attacks organized by Golden Dawn — suggests a police-regime with almost no respect to human life.

Under stricter requirements of acquiring citizenship and with an inadequate asylum system, immigrants and refugees are “trapped” in a country with substandard detention conditions at camps and prisons. Despite reported improvements at the appeal level of the asylum procedures, Greece has made very little progress in establishing a fair and humane system.

Police mistreatment and xenophobic behaviuor from the authorities is a key factor in depriving immigrants and refugees of basic human rights. Allegations of torture and ill-treatment have been largely reported and condemned by international courts and human rights organizations.

Although the anti-racism bill, which is under discussion in Parliament, holds provisions/sanctions for hate speech and incitement to violence, it does not address problems regarding the reporting of racist incidents and the prosecution of racist violence.

Last, but not least, the fundamental right to education for all citizens is not yet granted. The country has been found discriminating against Roma children by segregating them in separate schools.

Women and children

The harsh economic conditions imposed upon Greek population seem to affect women and children more than others.

Even though the number of complaints from women is consistently low, both at a national and European level, documented domestic violence has increased by 47% in recent months. Verbal abuse, economic blackmail and sexual humiliation are among the most common types of violence against women.

Unemployment and precarious employment affect women more than any other social group. There are documented cases of work discrimination during pregnancy and maternity.

Unfortunately, marginalization of Greek women does not stop there. The unprecedented shocking story of 31 women, forcibly tested for HIV and prosecuted for intentionally causing grievous bodily harm, is strong evidence of a police-state that shows no respect to medical confidentiality and above all human dignity. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have accused Greece of violating human rights in the case.

The state of children in Greece is in no better position, in fact it is in a critical status. Almost 600.000 are living below the poverty line, while half of them lack the basic nutritional needs. Things are far worse, when it comes to refugees and asylum seekers: both women and children have been victims of xenophobic violence.

This article was originally published at indexoncensorship.org