28 Apr 2015 | Events, mobile

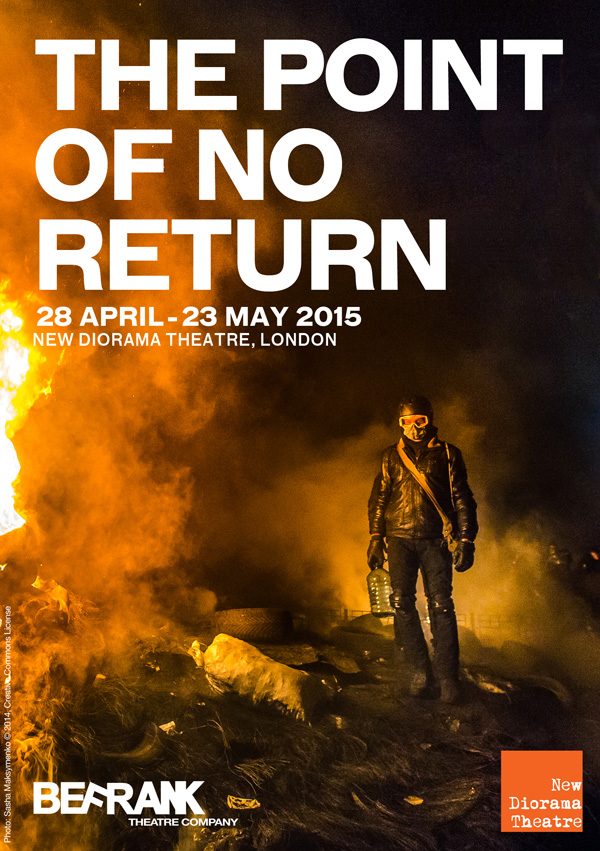

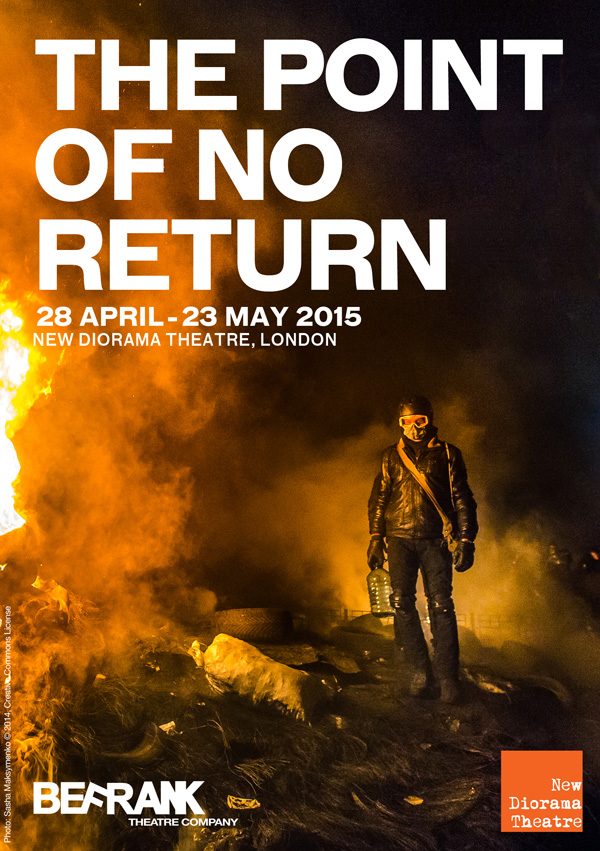

The Point of No Return, a new play based upon the last four days of Ukraine’s Maidan protests. From personally recorded real-life stories, extensive research and a journey to the heart of Ukraine, this story is based upon the revolution in Kiev in January-February 2014.

The performance on 6 May will be followed by a discussion including Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship:

- How important is freedom of speech to democracy?

- What form did censorship take in the Ukrainian revolution?

- How is censorship happening in the UK today?

Index joins BeFrank Theatre Company for an evening of debate and discussion about the future of free speech in the UK, Ukraine and across the world.

Where: New Diorama Theatre, London (Nearest Tube: Warren St)

When: Wednesday 6 May 2015, 7.30pm

Tickets: £12-£15 / Book here

An earlier version of this event provided the wrong date. It takes place on 6 May.

20 Mar 2015 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Russia, United Kingdom

(Photo: Demotix)

Vladimir Putin has returned to his people after a noted absence. Like Jesus Christ, but with a longer interlude. Was Vladimir Vladimirovich on paternity leave? Has he been ill? Did a botox injection go wrong? Was he fending off a coup? Has there, in fact, been a coup? Is this even the real Putin we see before us? Has he been replaced by a KGB cyborg?

It’s all delightfully old-fashioned, as if global politics was being staged by the Secret Cinema people. Any day now, someone will declare that Kremlinology is the hot new thing among urban ABC1 early adopters.

As ever, this column aims to be ahead of the curve. So what do we know?

The near-coincidence of the murder of Boris Nemtsov and the temporary disappearance of the president is bound to raise suspicion. I recall a conversation with an old colleague who grew up under the Soviet system. The idea of “cock up versus conspiracy” came up. I explained haughtily how people were wrong to see invisible hands guiding events when sheer human incompetence was almost always the explanation when things went weird. “Yes,” my friend replied. “But where I’m from, there usually is a conspiracy.”

Fair point.

The rounding up of some Chechens to pin the assassination of Nemtsov on feels almost contemptuous. It’s like the Russian authorities are not even bothering any more, or as if they are hoping to win a medal for sheer chutzpah in the face of the facts.

The suggestion that seems to be gaining ground is that Putin is no longer in charge, or perhaps won’t be for much longer. People such as The Economist’s Ed Lucas, The Times’s Roger Boyes and The Interpreter’s Catherine Fitzpatrick now speak deadly seriously about a return to the Cold War, with Putin outflanked by people who think he is not hardline enough.

A long blogpost on the current situation by Fitzpatrick outlines the scenarios. Former Prime Minister Primikov has issued an ultimatum to Putin, but Primakov himself could not command a move against Putin. Nemtsov had to go because a popular outsider could have caused problems for a palace coup. What is the involvement of Duma Deputy Delimkhanov, a cousin of Chechen President Kadyrov? What is the position of Viktor Zolotov, head of internal troops? It all becomes dizzyingly complicated, like an epic Russian novel, or Woody Allen’s parody of the epic Russian novel, Love and Death: “Alexei loves Tatiana like a sister… Tatiana’s sister loves Trigorian like a brother… Trigorian’s brother is having an affair with my sister, who he likes physically, but not spiritually… The firm of Mishkin and Mishkin is sleeping with the firm of Taskov and Taskov.”

Putin returned this week, not offering an explanation for his 10-day absence, but instead wryly commenting, during a press conference with the president of Kyrgyzstan, Almazbek Atambayev, that “life would be boring without gossip”.

Indeed, Vladimir Vladimirovich. Indeed.

The miasma to the east of the European Union’s borders has become more impenetrable and more obvious since the outbreak of fighting in Ukraine. Events there now take on the characteristics of the title of Peter Pomerantsev’s recent book Nothing Is Real And Everything Is Possible — a state of affairs where the brazen manipulation of truth is taken to staggering levels, to the point where an invasion is not an invasion, a war is somehow not taking place.

The Kremlin and its oligarch clients may not care much for truth, but one would hope that Cambridge University Press would.

CUP has been criticised by the organisers of a book prize for its refusal to publish a book on Russia by one of its own authors in the United Kingdom. According to The Observer, judges of the Pushkin House Russian Book Prize attempted review Putin’s Kleptocracy by Karen Dawisha for competition, but CUP refused to submit it.

“We attempted to get hold of the Dawisha book but the publisher would not submit it to us because of legal advice about UK libel laws. Our judges noted the book and said it raised important issues that deserved a wider audience, but unfortunately could not all get hold of a copy to pass judgment,” Andrew Jack, chair of the judges told the paper.

Disappointing indeed, and confirmation of the continual refusal by CUP to publish this book in the UK. The depressing thing about this, as noted in this column last year, is that CUP has not questioned the veracity of Dawisha’s work.

John Haslam of CUP wrote last year that: “We have no reason to doubt the veracity of what you say, but we believe the risk is high that those implicated in the premise of the book — that Putin has a close circle of criminal oligarchs at his disposal and has spent his career cultivating this circle — would be motivated to sue and could afford to do so. Even if CUP was ultimately successful in defending such a lawsuit, the disruption and expense would be more than we could afford, given our charitable and academic mission.”

I don’t like the language of “bravery” around publishers, but frankly, I’m beginning to doubt CUP’s commitment to the cause of academic freedom. More particularly, one wonders who is offering the company legal advice. Substantive reform to the libel law has made it considerably more difficult for foreigners to bring cases in London. Dawisha is not a fly-by-night hack, but a serious researcher. Conditions for publication are favourable. And faced with an entire Kremlin apparatus which has perfected the use of smoke and mirrors, the world needs all the information it can get.

CUP says it has contacted Dawisha to see “whether we might be able to find a compromise”. But considering they have already admitted there is nothing wrong with the book, it’s difficult to see what Dawisha’s side of the compromise might be.

This thing has dragged on too long now. For God’s sake, Cambridge; just publish the bloody thing.

This article was posted on 19 March 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Mar 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

A coalition of international press freedom organisations has hit out at a move to force some Russian “government-controlled” TV stations off Lithuanian airwaves.

Lithuania’s Committee on Radio and Television is reportedly considering, at the request of the government, to ban two Russian television channels from broadcasting to the Baltic country.

The channels in question — RTR Planeta and NTV Mir Lithuania — have in the past been handed down temporary suspensions of specific programs, according to the commission head Edmundas Vaitiekunas.

“If a ban is imposed on the whole channel due to repeated violations, I believe it should be longer … I believe it should be up to one year,” Vaitiekunas added in comments to the Baltic News Service earlier this year.

Russian state-owned media such as RT (formerly Russia Today), has come under fire for alleged distortion of facts in the their coverage, especially in relation to the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

In a letter this week to the Lithuanian President, media freedom organisations including the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers and the World Press Freedom Committee, argued that while they understand the objection to certain Russian broadcasts in “the current tense situation”, they consider a ban to be counterproductive and in contradiction of international free speech standards.

“If put into effect, bans on broadcasts across frontiers would almost inevitably be seized upon by the Russian authorities to justify bans on broadcasts by independent news media from other countries,” the letter states.

“It is an established conviction in free societies that the best answer to bad speech is more speech. We can see from the reaction to recent events in Moscow that there is a large public that is open to arguments, news reports and information to counteract official propaganda. The risk should not be taken to cut off such audiences from the free flow of information from outside their borders,” the group added.

This article was posted on Wednesday March 11 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Mar 2015 | mobile, News and features, Russia

As so often at the sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council, some interventions by states go unnoticed.

Under the famous ceiling of room XX created by Miquel Barcel in the Palais des Nations in Geneva, the on-going session of the Council is no different. Some of those unnoticed statements deserve our attention.

One in particular.

On Thursday, 5 March, one of the United Nations’ chief human rights voices, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, presented his first annual report to the council. It is his first since he took up the position of high commissioner for human rights in September 2014. From terrorism, torture and harassment of human rights defenders to the reorganisation of his office, the high commissioner’s report aims at presenting the state of human rights, the major threats against them and how he aims at building up his office to face those realities.

Al Hussein’s mandate, which Norway at the council called “an authoritative voice on human rights, built on […] repeated confirmation of its independence,” is what the Russian Federation in fact wants to silence.

Russia, which is today one of the 47 members of the council, was infuriated at the high commissioner’s statement presenting his report. It is traditional for states mentioned by international human rights mechanisms to accuse such instruments for being politicised and obeying “double standards.”

Russia went a step further by “condemning the high commissioner’s attempts to stigmatise any states for their acts or omissions in the field of human rights, even if they indeed took place.” Russia does not refer to politicisation or to attention the high commissioner would be giving to situations in certain countries only, but instead calls upon the United Nations voice for human rights to stop mentioning any country all together, whatever human rights violation took place in the country. In fact, Russia calls for the high commissioner to be silent.

Such a statement should not remain unnoticed because it sheds light on how Russia sees the international system; not one of standards and principles challenging states but rather one of obedience and muteness serving the states. The challenge Russia is facing with the high commissioner’s report is in fact a reflection of its disrespect for international law, be it in the way it has led suppression of civil society at home or its military activities in Ukraine, including the annexation of Crimea.

Because we must applaud those who stand firm for rights, we must also make sure that declarations by states who aim at silencing them do not go unnoticed. This one in particular.

This guest post was published on 10 March 2015 at indexoncensorship.org