2 Dec 2013 | Croatia, News and features, Religion and Culture

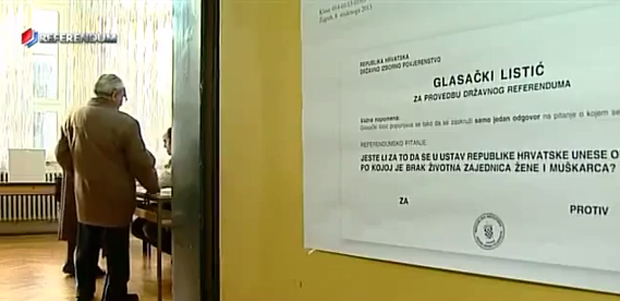

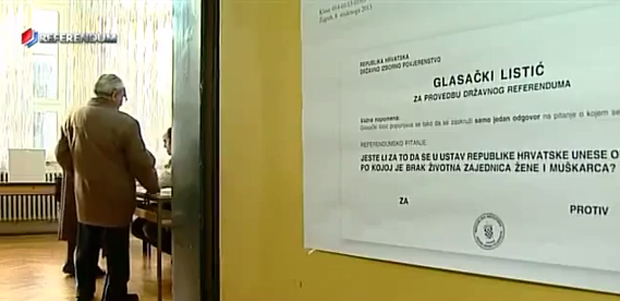

Croatians cast their votes on whether marriage should be constitutionally recognised as being between a man and a woman (Image: Mc Crnjo/YouTube)

Croatia’s voters moved Sunday to amend the country’s constitution to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The campaign had been orchestrated by the country’s religious institutions. Sixty-five percent of voters supported a change that effectively bars gay marriage.

The campaign used some interesting and controversial tactics. Religious teachers in schools threatened students that they wouldn’t get a passing grade if they did not provide proof of their families’ support for the constitutional change. This was reported by an English language teacher from Split, the second largest city in Croatia, to the inspection body of the Ministry of Education around mid-November.

“If this is the situation in Split I believe it is even worse in smaller towns”, concluded the teacher who did not want to sign her name.

Following this, the media received numerous letters from school teachers confirming that religious teachers around Croatia were blackmailing students to make sure their family members vote “for the protection of the family” — the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the referendum question.

“If the president of the country and other public persons can talk about voting at the referendum why can’t a religious teacher do so?” commented Sabina Marunčić, senior advisor for religious education at the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency.

Since the call for a referendum on 8 November, the campaign has been the main topic of discussion in Croatia, despite the country facing a severe economic crisis and an unemployment rate of 20.3 per cent. While Croatian law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, this definition does not exist in the constitution. A recent announcement of a new law on same-sex partnerships has caused conservative movements to come together in the initiative “In the Name of Family”. They started spreading fear about gay marriage being legalised, despite the centre-left government showing no intention to do this. A 2003 law on same-sex partnerships has been seen as practically useless because it secures only a few, less important rights, and only after a relationship breaks down.

For weeks all anyone talked about was who will vote “for” and who will vote “against”, in the first national referendum in the Republic of Croatia set up by popular demand. The Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, President Ivo Josipović and numerous ministers all came forth against introducing the definition into the constitution. A large portion of powerful media was also openly against it. However, public opinion polls showed that 68 per cent of the citizens would vote for the proposal; 26 per cent against.

In the referendum campaign, the Catholic Church have firmly been advocating “for”. It has has a strong influence in the country of 4.29 million, with 86 per cent declaring themselves Catholic according to the latest census, released in 2011. The initiative “In the name of family” which has succeeded in gathering signatures of 740,000 citizens in order to hold a referendum is also linked to the Catholic Church.

“The church did not want to start the initiative for a referendum but it wholeheartedly accepted In the Name of Family, whose numerous members are conservative Catholics close to certain Croatian bishops,” says Hrvoje Crikvenec, editor of the religious portal Križ života (“Cross of Life”).

“However, I believe that the entire organisation and initiative is supported more by politics, that is, a marginal political right-wing party Hrast, than Croatian bishops. They have now become more involved in the campaign in the hope of what would for them be a positive outcome of the referendum, which would ultimately show them as winners.”

The initiative’s leaders do come from the non-parliamentary right-wing party Hrast, as well as conservative associations opposing the introduction of sex education in schools, artificial insemination and abortion. Some of them have been linked to Opus Dei, a secretive Catholic organisation which has been strengthening its presence in Croatia. In the Name of Family and the fight against a possible equal standing of homosexual and heterosexual marriages has provided them with the support of a larger portion of the public.

The Catholic Church has undoubtedly helped the success of a In the Name of Family. Signatures were gathered in front of churches and elsewhere, even in universities. Cardinal Josip Bozanić had written a note instructing priests to encourage believers in masses to attend the referendum and vote for the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Group prayers for its success were also organised throughout Croatia in the lead up to the vote.

“We can’t blame the bishops for advocating the referendum from the altar because this is a part of the church’s program. They are more entitled do so than to say who to vote for at the elections, which they also do. However, it is inadmissible for religious teachers to influence children in schools,” university professor of philosophy and political commentator Žarko Puhovski says.

Despite Croatia being a majority Catholic country, every fourth marriage ends in divorce and a decreasing number of couples are deciding to marry.

“The church’s influence on citizens is far greater regarding political than moral views. Church morality is accepted in principle, but political views supported by the church gain additional power. That is why the referendum is causing a short-term increase in the influence of the church, which has for years been weakening,” Puhovski explains.

Church leaders are often complaining about the non-existent dialogue with the current, left-wing government, especially regarding the issues they consider to be related to religion – education of children, family care and marriage.

“The ultimate success of this referendum is in showing the power of the church in Croatia. It has shown the government that it can move masses of people so in the future, the government will have to think carefully before making any decision which could harm their interests,” said a group of Roman Catholic theologists in a joint letter made public on 29 November.

“The relationship between the church and the state has mostly been disturbed by militant statements of individuals from the Catholic Church leadership, which seem to be best served with a one common mindset rather than political and worldview pluralism,” sociologist and ex-ambassador for the Holy See, Ivica Maštruko says.

“We are not dealing with a normal criticism of the current social state and relations, but bigotry, inappropriate discourse and civilisational and religious malice,” Maštruko added.

An example of such a discourse is provided by reputable former minister and theologist Adalbert Rebić who, earlier this year, was quoted as saying: “The conspiracy of faggots, communists and dykes will ruin Croatia.” Pastor Franjo Jurčević was convicted for publishing homophobic and extremist posts on his blog.

But in the campaign for the referendum the Catholic Church was joined by representatives of the other most influential religious communities in Croatia – Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Baptists and the Jewish community Bet Israel. Together they supported the referendum and invited the believers to vote in order to “secure a constitutional protection of marriage”. Religious communities in Croatia are usually rarely seen forming such shared views.

“The most interesting thing is the agreement between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church which have in the past twenty years completely missed the chance to initiate reconciliation, dialogue and co-existence during and after the wars in ex-Yugoslavia. Religious communities in the region can obviously agree only when they find a common enemy, which in the case of this referendum are LGBT persons,” Cirkvenec says.

Žarko Puhovski considers it indicative that religious communities in Croatia succeed in forming shared views only with regards to sexual morality.

“They have failed to reach a consensus on any other moral or political issue,” he concludes.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society

Urooj M, a former DJ on a Pakistani FM radio channel, also a film aficionado, was incredulous when she found the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had blocked the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

She tweeted: “SERIOUSLY #PAKISTAN, WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU BAN #IMDB!!! COME ON, SERIOUSLY!!!???!!!! #FirstYoutubeNowIMDB #WTF.”

This widely used online entertainment news portal, a prominent source of reliable news and box office reports regarding films, television programmes and video games from all over the world, was blocked on 19 November, but the ban was lifted by 22 November.

Pakistan is notorious for blocking websites. It has banned more than 4,000 websites for what it considers objectionable material, including YouTube, in 2012 for a film that was deemed blasphemous by Muslims around the world. In 2011, in a particularly ill-thought-out move it announced censoring text messages containing swear words. In 2010, after a decision by the Lahore High Court, Facebook was blocked as a reaction to the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad’ page that was seen as offensive to the prophet.

Users were given no reason for this sudden and selective ban. However, Omar R. Quraishi, a journalist had tweeted: “PTA official declined to give specific reason for ban on IMDB – said is placed for 3 reasons: “anti-state”, “anti-religion”, “anti-social”.

While these “targeted bans” are small irritants in his life, as he can easily by pass them, Ali Tufail, 26, a Karachi-based lawyer, finds them wrong on principle as he sees them infringing upon the fundamental rights of the citizen as given in Article 19 and 19 A of Pakistan’s Constitution.

He said the government must give users sound “reasons” why they block a certain website and “what benchmarks or what standards are used to come to the decision to enforce these sudden bans” and if there is a committee that takes these decisions, “we must be told who these people are.”

The same was endorsed by Nighat Dad of Digital Rights Foundation (DRF). “We strongly oppose any form of censorship employed on citizens, curbing their basic right to information.”

However, netizens believe the ban was enforced to block the movie trailer for The Line of Freedom, a film that highlights the issue of the crises in Balochistan province showing Baloch separatists abducted by Pakistani security agencies without charges in a bid to stamp out rebellion.

“Our team did a quick survey with the help of tweeters around the country,” said Dad. “We checked various other movie titles but only Line of Freedom seemed to be blocked on IMDb and several other websites were accessible otherwise.” The DRF termed it an “unprecedented event” because the government had “used all sorts of means to curb the dissidents’ views” from Balochistan.

“I didn’t even know there was a movie by this title which was giving the government so much heartburn and so I just had to see what was so unsavoury that the government had to block the entire website,” said Dad who watched the whole 30 minutes or so of it by circumventing the various firewalls. “This is what happens, when you forcibly close the internet, word gets around and people get curious!”

Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of the online Baloch Hal, who sought asylum in the United States, is not surprised at the ban. His own newspaper was blocked in November 2010 and even now the ban has not been completely lifted, he says. “Since 2010, it has been available in some parts of the country and not others and access has not been very consistent,” he said adding there were hundreds of other Baloch websites, “mostly those supportive of the nationalists that have been blocked”.

But Tufail added: “This is one battle which the government would find difficult to win as newer, maybe more objectionable [to Pakistani state] websites, will keep popping up which they would never be able to keep pace with,” terming such bans an “exercise in futility”.

There could be some truth in the story of the ban on the Baloch film. Because their voices remain unheard, several family members made a 700km journey on foot from Quetta to Karachi to see if that would make a difference.

Naziha Syed Ali, a journalist at English-language daily Dawn, had recently visited Awaran, a stronghold of the separatists in Balochistan, which had been badly affected by the earthquake on September 24. She said she got a sense of “hostility expressed mainly towards the army and paramilitary rather than Pakistan per se. Then again, the army is seen as a symbol of the country, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Ali said “More than fear, they don’t want to take help from what they see as an occupation force.”

According to her the “feelings of alienation have been greatly exacerbated by the issue of the missing people and the kill-and-dump tactics”.

In addition, while Ali found there to be “sufficient food for now”, there was dire need for health services and proper shelter “as the tents that have been distributed are not warm enough for winter”.

The problem is the army is not allowing international and local non-governmental organisations to carry out any relief work there. Instead, the charities run by religio-political organisations and even banned outfits are seen freely roaming about. For years, the state has kept a stony silence over the issue of the disappearances of the Baloch nationalists. Rights group say if the state lets the various organisations into the region, their dark secrets about grave human rights abuses, for now a national shame, may become a problem for it on the international front.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Nov 2013 | Academic Freedom, Belarus, Europe and Central Asia

Last summer it was announced that the Faculty of History of the state university in Hrodna, a regional centre in the West of Belarus, ceased to exist. A school of historic science known since 1954 was united with the Faculty of Tourism and Communication. This was the final revenge the authorities took on historians who dared to present the past of their city and their nation in a way that differs from the “official line.”

In the beginning of 2013 a group of historians of Hrodna State University published a book about the history of their city. Andrei Charnikevich, one of the authors of the book, was fired from the university; his sacking wasn’t done according to proper legal procedures and took longer than Siamion Shapira, a local governor, wanted. It ended up with him sacking the rector of the university, Yauheni Rouba. The governor’s instruction to a newly appointed rector was to “pay attention” to other lecturers and professors who were considered “disloyal”; all of them named. Viachaslau Shved was the next historian fired. Ihar Kuzminich, who taught law at the same university and was on that list as well, submitted a resignation letter himself and wrote an open letter to the governor in protest at the campaign of persecution against academia in Hrodna.

That was not the first instance of “ideological clear-up” in Belarusian universities. In 1990s Aliaksandr Kazulin, then a rector of the Belarusian State University, the major university in the country, received similar instructions to prevent teachers and students from oppositional activities. The irony of history made Kozulin an oppositional candidate at the Presidential election of 2006 (and he received no support from his former university during the campaign), and later a political prisoner.

But Hrodna University has not really been a centre of political or civic movements. It has always been one of the best educational institutions in Belarus. It has been quite active in adopting and implementing European standards of higher education. The authorities did not think of its professors as “disloyal” – they liked to show the university to foreign delegations and experts as exemplary to boast of achievements of the Belarusian education system.

To understand what happened in Hrodna, one has to take into consideration peculiarities of the system of higher education and its management in Belarus. Formally, all universities report to the Ministry of Education. The current minister of education, Siarhei Maskevich, is a former rector of Hrodna University; he was the one who launched teaching innovations and consolidation of the financial situation of the university. Can a minister destroy what he himself started? In Belarus, he can.

Belarusian ministers are not independent; they just implement policies as instructed by the Presidential Administration. Just as governors, like Siamion Shapira, and down to university rectors – they are all appointed by the President of the country; all candidates for these positions are carefully chosen and checked by the KGB and other authority structures. Thus, every official in this “power vertical” depends on the head of the state. No one is elected; the institute of self-governance is destroyed as such, it is substituted on all levels by state governance. It is true with any area and sphere of activities, including education.

Universities in Belarus have no autonomy; thus, academic freedom is seriously compromised. In fact there has never been any. Even in the first half of 1990s, when universities were allowed to elect their rectors, they were financially reliant on state subsidies, so they were not independent. But even such a nominal formality as elections of rectors was eliminated. Rectors of private universities are appointed by the authorities as well. Any attempts to protest leads to disastrous effects. In 2004 the European Humanities University had to stop its operation in Belarus after its staff protested against the fact their rector had to be appointed by the country’s president. They refused even after the Ministry of Education suggested appointing Anatoly Mikhailov as the rector, the same person who was elected by the staff – it was a matter of principle, and the principle of academic freedom was the key. The EHU had to go in exile and restored its activity in 2005 in neighbouring Lithuania.

Appointed rectors can stay in their positions as long as they satisfy those who appointed them, i.e. the Presidential Administration. The way to satisfy those “employers” is not by defending academic freedoms and rights of professors and students; it is merely by obeying orders and staying “loyal” to state ideology.

Professor Rouba, a previous rector of Hrodna State University, did not reject an order to “clean up” his university – he was just not in a hurry to fulfil it. And this is how he irritated the authorities, thus losing his job as the head of the university. Because in the end it is not about an alleged “danger” any “disloyal” professor poses to the state – it is about the system that requires orders to be executed, promptly and carefully.

The authorities can see “disloyalty” in anything. Ihar Kuzminich, the law professor of Hrodna University, wrote a textbook on human rights for schools a couple of years ago. The mere topic of the textbook suggested the Ministry of Education could not approve it. The book was used during informal workshops and training sessions on human rights. But it was not the real reason for Kuzminich to end up on the “disloyalty black list” and eventually lose his job. It was because of the fairy tales he writes. Characters of his tales live in a modern city and fight for their rights. Such a metaphor appeared to be more dangerous for the regime than textbooks.

It might seem absurd, but this is a reality in Belarus. Monitoring, conducted by the Agency of Humanitarian Technologies, gives a lot of evidence of persecution for professional activities. We can talk about the employment ban in the system of education of the country. Hundreds of teachers and university professors were persecuted and lost their jobs in Belarus. Such instances cover almost every filed of learning, but most of cases are noted in humanities; the repressed academics are historians, economists, sociologists, pedagogues.

Last year Belarusian Ministry of Education attempted to join the Bologna Process that unites universities all throughout Europe, including post-Soviet region. The authorities decided to take this step as they have started to see the clear economic benefits from joining, through the export of educational services. Belarusian universities have been quite popular with foreign students, especially ones from China, Vietnam, Turkmenistan and some other, predominantly Asian countries. But recent years showed a decrease in interest in Belarusian higher education, because diplomas of Belarusian universities are not recognised in many countries. Joining the Bologna Process is supposed to solve this problem and attract more foreign students.

The Presidential Administration approved the idea, and the Ministry of Education launched the whole programme of bringing Belarusian standards of higher education in line with European ones – for the exception of two of them, namely autonomy of universities and academic freedoms. These two principles are considered by the Belarus Ministry of Education to be “insignificant”.

Infrastructural changes in Belarusian universities were quite vast and intensive; they look quite like European universities — “cheaper versions”, perhaps. But what is clear, is the absence of academic freedom and autonomy, which are the two fundamental features of a university. They distinguish it from other educational institutions, like technical schools, religious or military colleges and extension courses. Rectors got used to obeying orders; the academic community got used to abstaining from disagreeing.

A group of enthusiasts, professors, students, experts, public figures, decided to create a public Bologna Committee in Belarus. Its aim is to promote and protect academic freedoms and an idea of autonomy of universities in the country. The main paradox of the committee is that it promotes the values of the Bologna Process –- but in fact it impedes Belarus joining it, rather than fosters it. There is, however, no other way; a country that fights the dissent and suppressed free speech, and thus violates the main principles of the Bologna Process, cannot be accepted as a member of it.

There is a question if we can call Belarusian institutions of higher learning “universities” at all. A process of education seems to be going on there; this process resembles in a way the one in European universities. But it is an illusion to a great extent. Without a real academic freedom and independence there can be no university. Once this are restored Belarus will be ready to integrate into the European system of education – but not before.

21 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, India

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

Full report in PDF

(2) CRIMINALISATION OF ONLINE SPEECH AND SOCIAL MEDIA

The criminalisation of online speech in India is of concern as the authorities have prosecuted legitimate political comment online and personal views expressed on social media. New free speech opportunities offered by social media usage in India have been diminished after the introduction of provision 66A of the IT Act and the arrest of a number of Indian citizens for posting harmless content.[20] This chapter looks at how Section 66A constitutes a significant impediment to freedom of expression and will demonstrate the need to reform the law.

In 2011, Communications Minister Kapil Sibal asked Google, Facebook and Yahoo! to design a mechanism that would pre-filter inflammatory and religiously offensive content.[21] This request was not just, as noted at the time, technologically impossible, it was also a clear assault on free speech. The request demonstrated that even if Section 66A were reformed, further work would still be needed to prevent politically motivated crackdowns on social media usage.

Section 66A of the IT Act is both overly broad and also carries a disproportionate punishment. The section punishes the sending of “any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character” or any information meant to cause annoyance, inconvenience, obstruction, insult, enmity, hatred or ill will, among other potential grievances. The provision carries a penalty of up to three years imprisonment and a fine.

IT (Amendment) Act 2008

66A: Any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device, —

(a) any information that is grossly offensive or has a menacing character; or

(b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device; or

(c) any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

Much of the 2008 law historically stems from the 1935 UK Post Office (Amendment) Act, which related to telephone calls and telegraph messages. Rather than update the law to remove this dated provisions, the Indian government decided to extend them to new technologies.

Of particular concern is that there have been a number of arrests made under Section 66A for political criticism on Facebook, Twitter and even via private email. This is a worrying trend that may indicate an intolerance towards public interest speech about politicians that ought to be protected. Criminal and civil cases have also been brought against dozens of internet companies for failing to remove content deemed by some to be defamatory or religiously offensive.[22] Indians new to social media are learning to navigate the red lines of free speech or face prosecution. This degree of censorship is unwelcome in a functioning democracy.

For example, two women were arrested in 2012 for their use of Facebook, one for criticising disruptions in Mumbai during a politician’s funeral and the other for “liking” her friend’s comment (see case study). The two women were arrested under Section 66A and their arrest soon sparked public outrage, with the Times of India newspaper denouncing “a clear case of abuse of authority” by the police.[23]

Case study: Facebook arrests

On Sunday 18 November 2012, a 21-year-old Mumbai woman, Shaheen Dhada, shared her views on Facebook on the shutdown of the city as Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray’s funeral was being held. Her friend Renu Srinivasan “liked” her post. At 10.30 am the following day, they were both arrested and were ordered by a court to serve 14 days in jail. Hours later, they were eventually allowed out on bail after paying two bonds of Rs. 15,000 (£145) each.

Dhada had posted, “Respect is earned, not given and definitely not forced. Today Mumbai shuts down due to fear and not due to respect”. A local Shiv Sena leader filed a police complaint and Dhada and Srinivasan were booked under Section 295 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) for “deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” Subsequently they were also charged under Section 505 (2) of the IPC for making “statements creating or promoting enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes”, and the police added Section 66A of the IT Act to the list of charges.

After a significant public outcry, charges were finally dropped. Other recent examples include a 19-year-old, Sunil Vishwakarma, who was detained for a derogatory Facebook post against a politician.[24] “We have received a complaint that he posted some objectionable comments against Raj Thackeray”, said an officer at Palghar police station. The police did not charge the teenager. He was questioned and later taken to a special cyber-crime cell before being released. In October 2012, Ravi Srinivasan, a 46-year-old businessman in the southern Indian city of Pondicherry, was arrested for a tweet criticising Karti Chidambaram, the son of Indian Finance Minister P Chadambaram. He was later released on bail.

Popular outrage over the police’s misuse of Section 66A led the Minister for Information and Communication Technology, Kapil Sibal, to issue a guidance to states on how to implement the controversial section of the IT Act.[25] However, there remain ongoing issues relating to political interference in law enforcement itself and to the vague wording of the law itself, with the use of the terms “annoyance” and “inconvenience” overly broad, giving the authorities a wide scope to criminalise comment and opinion.[26]

Despite top-down resistance to change, there is a push for reform of the law. Beyond the guidelines issued in late 2012 to prevent misuse of Section 66A, a revision of the law itself is still needed to prevent warrantless arrests and prosecutions. Civil society and political pressure to reform the law have recently increased. In 2012, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi and journalist Alok Dixit founded Save Your Voice, a movement against internet censorship in India that opposed the IT Act and demands democratic rules for the governance of internet.[27] The Minister for Information and Communication Technology has acknowledged there is an issue over the interpretation of 66A: “It’s very difficult to interpret the act on the ground. If you give this power to a sub-inspector of police, it is more than likely to be misused”.[28] Yet, he has defended the controversial law and resisted change, justifying his decision by saying that there was “no rampant misuse”.[29]

In January 2013, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament, filed a petition to the Indian Supreme Court challenging Section 66A and the Information Technology [Intermediaries Guidelines] Rules for being “arbitrary and uncanalized, […] and in violation of the rights available to citizens under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution.” Five other petitions related to the IT Act are currently under review by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has directed that pleadings will be listed before the Court in the first week of January 2014. This is a welcome step but the Supreme Court must deal with these cases as a matter of urgency and even in the case of success for the petitions, these decisions will require political will to be implemented.

The criminalisation of online speech and social media usage is a serious threat to freedom of expression in the country. The use of “offence” to silence political criticism online jeopardises free speech as a fundamental right necessary for public debate in a democracy. It is clear that there is the need and the public will to reform the law. The arrests and prosecution of citizens for innocuous messages has tarnished India’s image as the world’s largest democracy. While the 2014 General Elections offer a window of opportunity for change, the Indian authorities must undertake reform of the IT Act and end resistance to change.

CONTENTS

Introduction and Recommendations | 1. Online censorship | 2. Criminalisation of online speech | 3. Surveillance, privacy and government’s access to individuals’ online data | 4. Access: obstacles and opportunities | 5. India’s role in global internet debates | Conclusion

This report was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[20] BBC News, ‘Outrage at India arrests over Facebook post’ (20 November 2012), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-20405193 accessed on 5 September 2013.

[21] The Hindu, ‘Sibal warns social websites over objectionable content’ (6 December 2011), http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sibal-warns-social-websites-over-objectionable-content/article2690084.ece accessed on 5 September 2013.

[22] Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the Net 2012: India’, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/india accessed on 9 September 2013.

[23] Times of India, ‘Shame: 2 girls arrested for harmless online comment’ (20 November 2012), http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-11-20/mumbai/35227016_1_police-station-shiv-sainiks-police-action accessed on 5 September 2013.

[24] Indian Express, ‘Now Palghar police detain 19-year-old for Facebook post on Raj Thackeray’ (28 November 2012), http://www.indianexpress.com/news/now-palghar-police-detain-19yrold-for-facebook-post-on-raj-thackeray/1037462/ accessed on 5 September 2013.

[25] New guidelines require that no less than a police officer of a rank of Deputy Commissioner of Police will be allowed to permit registration of a case under provisions of the Information Technology Act.

[26] Some provisions in Section 66A were purportedly drafted to prevent spam – messages typically sent in bulk and unsolicited.

[27] Save Your Voice, a movement against web censorship, http://www.saveyourvoice.in/p/about.html

[28] Lakshmi Chaudhry, First Post, ‘The real Sibal’s law: Resisting Section 66A is futile’, http://www.firstpost.com/politics/the-real-sibals-law-resisting-section-66a-is-futile-541045.html?utm_source=ref_article accessed on 18 November 2013.

[29] Nikhil Pahwa, Medianama, News and Analysis of Digital Media in India, ‘Sibal defends IT Act Section 66A in Parliament: Notes’, http://www.medianama.com/2012/12/223-sibal-defends-it-act-section-66a-in-parliament-notes/ accessed on 18 November 2013.