5 Mar 2015 | Awards, mobile, Russia

Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia is an NGO network dedicated to improving transparency and exposing human rights abuses in the Russian military. It aims to provide soldiers’ families with reliable information, which the notoriously secretive Russian military has kept private. It also provides legal advice for Russian soldiers and their families, and to conscientious objectors.

“The organisation operates from general principles of human rights and the rule of law. We are in favour of contract service for the Russian armed forces whereby men are recruited on the basis of their intellectual, physical and spiritual readiness. We speak out against forced conscription and believe a transition to a professional army would significantly improve human rights and relations between the military and civilians,” Ella Polyakova from Soldiers’ Mothers St. Petersburg branch told Index on Censorship via email.

The Soldiers’ Mothers groups were established in 1989, in the last days of the Soviet Union. One of their first responsibilities was to personally negotiate for political prisoners left behind by the Russian army in former socialist republics. The group also calls attention to brutal “dedovshchina” or hazing tactics used on junior soldiers, ranging from beatings and sexual abuse to torture and enslavement. Because the abuse is perpetrated by senior officers, it often cannot be officially reported, leading to distorted figures. For example, in 2010 the committee reported 2,000 deaths from hazing, while Russia’s Defence Ministry declared only 14.

Vladimir Putin has insistently denied that Russian forces have had any involvement with Ukraine’s civil war, in which pro-Russian separatists have been fighting government forces since April 2014. Officially, any Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine are volunteering, not acting on behalf of the Kremlin – in December 2014 Putin described such men as answering “a call of the heart”.

The secrecy surrounding the disappearances of soldiers has mirrored past operations by the Russian military. During conflicts in Afghanistan and Chechnya in the 1980s and 1990s, the Russian army only landed planes carrying soldiers’ bodies at night, to cover up escalating casualty figures.

From August 2014, Soldiers’ Mothers members began revealing that their investigations had found that many wounded or killed Russian soldiers had been fighting in Ukraine. Head of the committee Valentina Melnikova announced that her research showed that between 10,000-15,000 Russian troops had been sent over the border in August. Her information was derived from mothers and wives of servicemen who were sent on military exercises close to the Ukraine border, and who subsequently stopped communicating with their families.

There has been a systematic silencing and smearing of committee members who have reported on Ukraine deaths. Lyudmila Bogatenkova, head of the Budennovsk branch of Soldiers’ Mothers, was arrested and charged with a four-year-old fraud conviction, after she announced that 11 Russian soldiers were killed fighting in Ukraine. After her release she had to be treated in hospital.

Polyakova demanded a government investigation after receiving information about 100 Russian soldiers allegedly killed and 300 wounded in Ukraine. Soon after, her branch was labelled a “foreign agent” by the government – even though the committee of Soldiers’ Mothers no longer receives foreign funding, one of the prerequisites of the classification. Her committee faces serious problems as a result, including being subjected to complex reporting requirements, and additional inspections and controls.

“To make matters worse, after the organisation was put on the register, a film crew from a state television channel burst into our offices and blackened us with dishonest coverage of our work,” Polyakova told Index. “Later that night, someone smashed the windows of our director Olga Alexeeva’s car. Human rights activists linked to Soldiers’ Mothers received many threats and insults by text message and email.”

But despite the pressures they face, they intend to continue their work, and also set up “a human rights information and analysis agency” to increase contact with other NGOs and the media.

“We are glad that we are able work effectively to defend human rights and to take part in positive changes in the lives of our citizens,” the group said of their Index award nomination. “It is nice to know that this work is valued by our colleagues.”

With additional reporting by Will Haydon

20 Feb 2015 | Awards, mobile, Russia

Journalism nominee Ekho Moskvy

Ekho Moskvy (Echo Moscow) is an independent Russian radio station. One of few media outlets that is critical of Vladimir Putin’s regime, it is revered by many as the last bastion of free speech in the country.

Ekho was set up in 1990 by radio veterans jaded with Soviet propaganda, and has taken an interrogative stance towards Russia’s government ever since. Its focus is on maintaining balance – it airs pro and anti-Kremlin voices in equal measure. Its editor-in-chief, Alexei Venediktov, has often done battle with Putin and his government. In 2012 Putin is said to have remarked that Ekho served foreign interests, and “pour[ed] diarrhoea over me day and night”.

During the 1990s, Russia’s news outlets developed into a world-respected critical force. But since Putin came into power in 1999, the media’s role as objective watchdog has diminished, and most news organisations are now resolutely pro-Kremlin.

In 2014, Russia attracted significant international condemnation over its involvement with the Ukraine civil war. In response, Putin began to cultivate an us-versus-them atmosphere in his country which saw his popular approval ratings grow to 80 per cent. Such an atmosphere has little room for dissidence, and anti-government voices have been silenced. The remaining politically independent news outlets are gradually being banned, crippled or brought in line with the Kremlin.

In the autumn 2014 edition of Index on Censorship magazine, contributor Helen Womack interviewed Sergei Buntman, the station’s co-founder. Womack wrote:

“There are various theories as to how Ekho gets away with it. Some say the radio and associated website, with a following of nearly one million in Moscow and three million in the regions, is tolerated because it allows the intelligentsia to let off steam, with little impact on the rest of the TV-watching country. Others say it allows the Kremlin to argue to the world that free speech is not dead in Russia. And one theory has it that Kremlin staff themselves depend on Echo to be properly informed because they can’t rely on their own propaganda.”

Buntman has another explanation, Womack wrote. “It’s no miracle and no wonder,” he told her. “You’d be surprised but a lot actually depends on us. Many journalists just give in too soon; they give up at the first hurdle.”

Last year was especially turbulent for Ekho Moskvy, which fought Putin’s media crackdown on many fronts. Its website was banned in March by Roskomnadzor, Russia’s media watchdog, after it published a blog post by leading opposition figure Alexei Navalny. In December, the Dagestan limb of the station was shut down by Roskomnadzor for no official reason.

The outlet was issued its own warning from Roskomnadzor in October. The watchdog cited two interviews aired by Ekho with journalists who provided first-hand accounts of fighting in eastern Ukraine. Roskomnadzor said the programme contained “information justifying war crimes,” and ordered the station to take down the interview transcripts from its website. Two cautions from Roskomnadzor in a year usually leads to an organisation’s closure.

Alexander Plyushchev, who conducted the banned interviews, was fired by Ekho’s owner Gazprom-Media in November, though Venediktov would later reject the dismissal and reinstate Plyushchev. Ostensibly, Plyushchev was sacked because of an insensitive tweet he had sent about the death of the son of Putin’s chief of staff. But Venediktov has suggested that Plyushchev’s controversial interviews the month before are behind the firing by Gazprom-Media owner Mikhail Lesin, Putin’s former press minister.

Despite challenges, the station’s news coverage was commended for staying true to its spirit of independence. Reports on the fighting between pro-Russian separatists and the Ukraine government were praised for their even-handedness, at a time when the majority of Russian media took a staunchly pro-Kremlin approach. As a result, Venediktov and his colleagues have appeared on several blacklists and have been labelled “enemies of Russia”.

This article was posted on 20 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, mobile, Press Releases

* South American cartoonist and mafia investigator shortlisted for 2015 Freedom of Expression award

* Other nominees include a jailed Moroccan rapper, the lawyers who fought Turkey’s social media ban, and a Mexican news platform fighting cartel-enforced media blackouts

* Judges include Martha Lane Fox, Mariane Pearl, Keir Starmer, and Elif Shafak

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for depicting government corruption, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning charity Index on Censorship. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism; arts; campaigning; and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of a unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

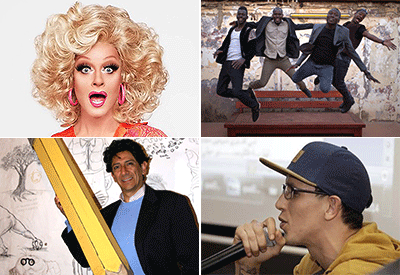

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist “Bonil” – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad ‘El Haqed’ Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who successfully overturned Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatagr who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

More detail about the nominees is included below.

The winners will be announced at a ceremony at The Barbican, London, on March 18.

The judges for this year’s awards – now in their 15th year – are digital campaigner and entrepreneur Martha Lane Fox; bestselling Turkish novelist Elif Shafak; journalist and campaigner Mariane Pearl; and human rights lawyer Keir Starmer.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact: David Heinemann on 0207 260 2660. Photos of the nominees are available at www.indexoncensorship.org

Notes for editors

The shortlisted nominees:

Journalism

Lirio Abbate (Italy);

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia);

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola);

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

Arts

“Bonil” (Ecuador);

Panti Bliss (Ireland);

Songhoy Blues (Mali);

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia);

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey);

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan);

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany);

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia (Russia)

Digital Advocacy

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary);

Nico Sell (USA);

Syria Tracker (Syria);

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

Index on Censorship, founded in 1972 by poet Stephen Spender, campaigns for freedom of expression worldwide. Its award-winning quarterly magazine has featured writers such as Vaclav Havel, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Philip Pullman, Salman Rushdie, Aung San Suu Kyi and Amartya Sen.

The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards are now in their 15th year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim, and Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

The awards are sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers (sponsors of the Campaigning award); The Guardian newspaper group (sponsors of the Journalism award); Google (sponsors of the Digital Advocacy award); and Sage Publications. The Digital Advocacy award is decided by public vote between January 27 and February 15.

Nominees for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015

Journalism

Lirio Abbate

Lirio Abbate is a Rome-based journalist working for the weekly news magazine L’Espresso. He specialises in investigating the criminal activity and political connections of Italian mafia groups, from whom he is routinely subjected to violent threats. Abbate has written four books about mafia groups since 1993. The most recent, Fimmine Ribelli or Rebel Women (2013), illustrates the severe plight of women living under the sway of the ‘Ndrangheta’ – the Calabrian mafia. Abbate is also a leading member of press freedom NGO Ossigeno Per L’informazione (Oxygen via information). In 2011 he founded an anti-mafia literary festival called Trame, which has taken place annually in the heart of Calabrian mafia territory.

Safa Al Ahmad

Safa Al Ahmad has spent the last three years covertly filming an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province. Her 30-minute documentary, Saudi’s Secret Uprising, was broadcast in May 2014, and has drawn wide attention to the violent and bloody protests. Al Ahmad took enormous risks in her regular filming trips. First, as a woman travelling alone, she drew the attention of Saudi officials in a country in which women have limited control over their day-to-day lives. Second, she carried a camera full of footage of dissent. Saudi Arabia is ranked by Freedom House as one of the most restrictive Arabic countries in terms of free expression – Al Ahmad would almost certainly have faced severe punishment if caught filming.

Rafael Marques de Morais

Rafael Marques de Morais is an Angolan journalist and human rights activist. Since 2008 he has run anti-corruption watchdog news site, MakaAngola.org. Marques de Morais exposes government and industry corruption, as well as human rights violations. In 1999, he was arrested and detained for 40 days without charge, and denied food and water for days at a time, following an article critical of the Angolan president. His six-month sentence for defamation was finally suspended on condition that he wrote nothing critical of the government for five years. Within three years he was again reporting abuses. He currently faces nine charges of defamation for reports on human rights abuses committed during diamond mining operations.

Ekho Mosky (Echo of Moscow)

An independent Russian radio station, Echo is one of few media outlets that is critical of Vladimir Putin’s regime and describeded by many as the last bastion of free speech in the country. It has an estimated audience of 7 million people across Russia. Echo was set up in 1990 by radio veterans jaded with Soviet propaganda, and has taken an interrogative stance towards Russia’s government ever since. Its focus is on maintaining balance – it airs pro- and anti-Kremlin voices in equal measure. Editor-in-chief Alexei Venediktov has often battled with Putin. In 2012 Putin remarked that Ekho served foreign interests and “pour[ed] diarrhoea over me day and night”.

Arts

Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla

Bonil is the pen name of Xavier Bonilla, an Ecuador-based editorial cartoonist who draws for several national newspapers, particularly El Universo. For thirty years he has critiqued, lampooned and ruffled the feathers of Ecuador’s political leaders, earning a reputation as one of the wittiest and most fearless cartoonists in South America. More recently, Bonil has gained a new epithet – ‘the pursued cartoonist’ is how Spanish newspaper El Pais styled him in its list of the 12 Latin Americans in 2014 news. Twice in 2014 incumbent president Rafael Correa publicly denounced Bonil and threatened him with legal action – the first case was successful against Bonil, and the second is ongoing.

Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat

El Haqed, roughly translated as ‘the enraged’, is a Moroccan rapper and human rights activist. His music has publicised widespread poverty and endemic government corruption in Morocco since 2011, when his song ‘Stop the Silence’ galvanised Moroccans to protest against their government. He has been imprisoned on spurious charges three times in as many years, most recently for four months in 2014. Haqed believes that police had been looking for an opportunity to arrest him after the release of ‘Walou’ – Haqed’s 2014 album, which is banned from being sold or played in public. One officer at the scene was heard to say “I have scores to settle with you”. Haqed and his brother were beaten by police as they were detained.

Rory ”Panti Bliss” O’Neill

Rory O’Neill sees his it as his duty as “to say the unsayable”. A Dublin-based stand-up comedian and self-described accidental activist for gay rights, he has performed a comedy drag act under the name Panti Bliss for more than two decades. O’Neill rocketed to international fame in January 2014 after he and national broadcaster RTE were threatened with legal action for defamation following a TV appearance in which he identified homophobic writers and groups in Irish media. RTE edited out the offending segment on its online player, issued an apology and paid six individuals €85,000 of public money to settle the dispute. The apology prompted almost a thousand complaints to the TV station and triggered countrywide debate.

Songhoy Blues

Songhoy Blues is a four-piece “desert blues” band, based in Mali. It is made up of musicians who fled north Mali after militant Islamist groups captured the territory and implemented strict sharia law – including the prohibition of secular music – in spring 2012. Despite the lifting of sharia law many musicians continue to self-censor, fearful of the Islamist groups’ return and retribution. In 2014 Songhoy Blues went on a global tour, and also supported artists such as Damon Albarn and Julian Casablancas across Europe. Mojo magazine has named them one of 10 “new faces of 2015”. Their debut album, Music In Exile, will be released in February, and its lead single – Al Hassidi Terei, produced by Zinner – has received critical acclaim.

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi

Amran Abdundi is a women’s rights activist based in north-eastern Kenya. She runs the Frontier Indigenous Network, an organisation that helps women set up shelters along the dangerous border with Somalia. It offers first aid and support for rape victims, including moving them to a safer part of Kenya. As well as protecting citizens endangered by the guerrilla activities of Al Qaeda-linked group Al Shabaab, the organisation helps those fleeing drought and failed harvests in Somalia. Abdundi has established radio-listening groups for women, in which she encourages them to challenge repression and educates them about diseases such as tuberculosis.

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak

Yaman and Kerem are cyber-law experts and internet rights activists who have campaigned vigorously against the Turkish government’s increasingly restrictive internet access laws. Together, they have raised repeated objections to controversial internet law 5651. This law ostensibly blocks access to child pornography and other harmful content, but it is also used to censor politically sensitive content such as pro-Kurdish or left-wing websites. It has been used to block around 50,000 websites. Their advocacy efforts, including an appeal to Turkey’s highest court, forced the overturn of blocks on Twitter and YouTube in 2014.

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar is an Afghan journalist and the executive director of the media advocacy group Nai Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, which works to develop a free media in Afghanistan as the country develops a peacetime society.

A radio journalist for more than 10 years, Khalvatgar is also a member of Afghanistan’s Foundation Open Society Institute, working as media coordinator and acting country manager. Khalvatgar is also an active member of the Access to Information Law Working Group, a group of more than 15 media professionals and activists working for better access to Information Law in Afghanistan.

“Nazis against Nazis” (ZDK)

Rechts gegen Rechts was a guerrilla event that took place in Wunsiedel, Germany, in November 2014. It was designed to peacefully counter an annual neo-Nazi march through the streets of the small town where Rudolf Hess is buried. For every metre the marchers walked, money was raised for an anti-extremism, Nazi-rehabilitation charity ZDK. ZDK was set up in 2003 to tackle all forms of extremism – particularly religious and nationalist extremism. As well as rehabilitating neo-Nazi defectors, it recently began a project called Hayad – meaning ‘life’ in Arabic – which aims to de-radicalise Muslims who want to leave their families and join jihadist groups.

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia

The Union of the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia is an NGO network based in Russia, dedicated to improving transparency and exposing human rights abuses in the Russian military. It aims to provide soldiers’ families with reliable information, kept private by the notoriously secretive Russian military. It also provides legal advice for Russian soldiers and their families, and to conscientious objectors.

The first Soldiers’ Mothers groups were established in 1989, in the last days of the Soviet Union. In 2014, members began revealing that their investigations had found that many wounded or killed Russian soldiers had been fighting in Ukraine.

Digital Activism

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky

Atlatszo.hu is an investigative news outlet founded and managed by Tamás Bodoky, the main goal of which is to promote free, transparent circulation of information in Hungary. The website, which receives around 500,000 unique visitors per month, acts as watchdog to a Hungarian government which has increasingly tightened its grip on press freedom in the country. Through it, Bodoky produces investigative reports based on freedom of information requests, and instigates lawsuits in cases where its requests are refused. In 2014, the website has uncovered cases of state control of the media, election fraud, government corruption, tax fraud, and misuse of public funds.

Nico Sell

Nico Sell is a US-based entrepreneur and activist for online privacy and secure digital communication. Sell is the CEO of Wickr, a private messaging app with watertight encryption technology. Messages sent using the app ‘self-destruct’ after a length of time adjusted by the sender – from six days to one second – and are then overwritten by gibberish data on the sender’s and receiver’s phones, making them impossible to recreate. Every year at Defcon, Sell runs a nonprofit training camp for children and teenagers called R00tz Asylum, in which digital skills such as white-hat hacking techniques are taught.

Syria Tracker

Syria Tracker is a crisis-mapping platform, which collates and exhibits live data on human rights abuses and other welfare issues brought about by the Syrian conflict. Reports of killings, rapes, water and food tampering, and chemical attacks ongoing in Syria are geolocated and collated onto a live map by US-based volunteers. Syria Tracker synthesises two pre-existing data-sourcing platforms and this combination makes for meticulous accuracy, since data from one source is triangulated with the other, and unverified information is discarded. The news-tracking tool covers anti- and pro-Assad news sources to reduce potential bias.

Valor por Tamaulipas

Valor por Tamaulipas is a crowd-sourced news platform, based in Mexico and set up in 2012 to fill the void created by the region’s cartel-induced media blackout. Valor’s online followers – more than half a million on Facebook and 100,000 on Twitter – send in reports of cartel-related violence, such as shootings, robberies, or missing people. These reports are immediately curated and disseminated by the page administrator, with a hashtag such as #SDR (“situación de riesgo” i.e. situation of risk) attached. From its inception, Valor por Tamaulipas (which means “Courage for Tamaulipas”) has been under constant threat by cartels.

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

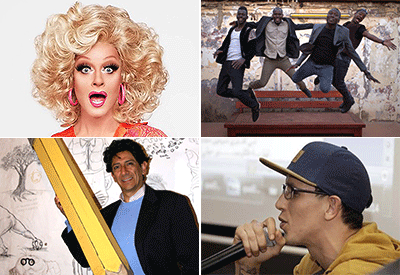

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org