17 Dec 2014 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Packed inside this issue, are; an interview with fantasy writer Neil Gaiman; new cartoons from South America drawn especially for this magazine by Bonil and Rayma; new poetry from Australia; and the first ever English translation of Hanoch Levin’s Diary of a Censor; plus articles from Turkey, South Africa, South Korea, Russia and Ukraine.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, authors from around the world including The Observer’s Robert McCrum, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak, and Nobel nominee Rita El Khayat consider which clauses they would draft into a 21st century version of the Magna Carta. This collaboration kicks off a special report Drafting Freedom To Last: The Magna Carta’s Past and Present Influences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”62427″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Also inside: from Mexico a review of its constitution and its flawed justice system and Turkish novelist Kaya Genç looks at recent intimidation of women writers in Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: DRAFTING FREEDOM TO LAST” css=”.vc_custom_1483550985652{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The Magna Carta’s past and present influences

1215 and all that – John Crace writes a digested Magna Carta

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson imagines a shock twist for King John

Battle royal – Mark Fenn on Thailand’s harsh crackdown on critics of the monarchy

Land and freedom? – Ritu Menon writes about Indian women gaining power through property

Give me liberty – Peter Kellner on democracy’s debt to the Magna Carta

Constitutionally challenged – Duncan Tucker reports on Mexico’s struggle with state power

Courting disapproval – Shahira Amin on Egypt’s declining justice as the anniversary of the military takeover approaches

Digging into the power system – Sue Branford reports on the growth of indigenous movements in Ecuador and Bolivia

Critical role – Natasha Joseph on how South African justice deals with witchcraft claims

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Brave new war – Andrei Aliaksandrau reports on the information war between Russia and Ukraine

Propaganda war obscures Russian soldiers’ deaths – Helen Womack writes about reports of secret burials

Azeri attack – Rebecca Vincent reports on how writers and artists face prison in Azerbaijan

The political is personal – Arzu Geybullayeva, Azerbaijani journalist, speaks out on the pressures

Really good omens – Martin Rowson interviews fantasy writer Neil Gaiman, listen to our podcast

Police (in)action – Simon Callow argues that authorities should protect staging of controversial plays

Drawing fire – Rayma and Bonil, South American cartoonists’ battle with censorship

Thoughts policed – Max Wind-Cowie writes about a climate where politicians fear to speak their mind

Media under siege or a freer press? – Vicky Baker interviews Argentina’s media defender

Turkey’s “treacherous” women journalists – Kaya Genç writes about dangerous times for female reporters, watch a short video interview

Dark arts – Nargis Tashpulatova talks to three Uzbek artists who speak out on state constraints

Talk is cheap – Steven Borowiec on state control of South Korea’s instant messaging app

Fear of faith – Jemimah Steinfeld looks at a year of persecution for China’s Christians

Time travel to web of the past and future – Mike Godwin’s internet predictions revisited, two decades on

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Language lessons – Chen Xiwo writes about how Chinese authors worldwide must not ignore readers at home

Spirit unleashed – Diane Fahey, poetry inspired by an asylum seeker’s tragedy

Diary unlocked – Hanoch Levin’s short story is translated into English for the first time

Oz on trial – John Kinsella, poems on Australia’s “new era of censorship”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Jodie Ginsberg writes about the power of noise in the fight against censorship

Index around the world – Aimée Hamilton gives an update on Index on Censorship’s work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Humour on record – Vicky Baker on why parody videos need to be protected

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Dec 2014 | Magazine, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

Index on Censorship autumn magazine

In September, Index on Censorship magazine launched a social media campaign which invited its readers to nominate a place which was symbolic of either free speech or censorship, with the winning locations being granted free access to the magazine app for one year.

Nominations came from all over the world and the winning places are Maiden Square in Ukraine, Gezi Park in Turkey and Wigan Pier in the north of England.

You can access the app on iPhone or iPad until 1 September 2015 at any of the three locations listed, by following these steps:

1) Visit the app store or iTunes, searching “Index on Censorship”

2) Download the FREE Index on Censorship app

3) Scroll through the issue to the final page, selecting “Tell me more”

4) Turn the “ByPlace” switch to the right

5) Click OK to activate

See some of the nominations Index magazine received in our Storify below.

For more information on subscribing to Index, click here.

3 Dec 2014 | Campaigns, Kazakhstan, Statements

The injunction banning distribution and publication of ADAMbol, a popular opposition magazine in Kazakhstan, is a clear violation of freedom of press and free expression.

The magazine has been accused of engaging in “extremist war propaganda” by Almaty City’s Department for Internal Policies. Some activists believe the magazine has been targeted over its coverage of Ukraine’s Maidan protests. In addition to ordering the closure of the magazine, the injunction from Almaty district court on 20 November also demands the confiscation of all printed copies of the magazine.

Cracking down on media is a well known tactic for authorities to silence dissent and stifle debate — and one Kazakhstan has made good use of in recent times. Since late 2013, over 30 media outlets have been closed in the country, over various administrative code violations or allegations of extremism.

Index calls on Kazakhstan’s authorities to end the assault on the media and respect their citizens’ right to free expression.

13 Nov 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society, Russia, United Kingdom

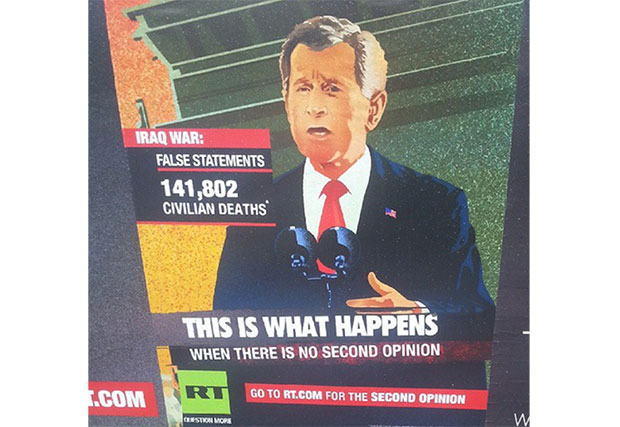

(Photo: Padraig Reidy)

There’s a poster near my house in London. It shows a poorly illustrated George W. Bush, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln early in the Iraq war, with the now infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner behind him. To his side, the tally of dead in the Iraq War (at least according to Iraq Body Count). Underneath is emblazoned the slogan: “This is what happens when there is no second opinion.” It is an advert for Russian propaganda channel RT (formerly Russia Today).

It’s a slightly muddled poster, but the signal is clear: did you feel lied to about the Iraq war? Watch RT.

Curiously, RT, which launched a UK channel on 30 October, seems to believe the poster doesn’t exist. A “report” on the RT website, dated 9 October, claims that the campaign of which this poster is part was “rejected for outdoor displays in London because of their ‘political overtones’”. The story goes on to claim that the “rejected” posters were replaced by ones that simply say “redacted”, before urging readers to download an RT app to view the ads on their phones.

But I have seen the poster. I even took a picture. Yet RT insists it has been banned, saying that outdoor advertising companies cited the Communications Act 2003, which “prohibits political advertising”. This prohibition is indeed to be found in the act, but only applies to broadcast advertisements, not billboard advertisements for broadcasters.

This is a fairly crude illustration of RT’s attitude to the truth. It is simply not an issue. What’s important is something that might sound true, something just about plausible, to suit the agenda (in this case, the agenda is threefold: one, to get people to download the app; two, to sow the belief that “they” are scared of RT; and three, to introduce the notion that political advertising is subject to a blanket ban in the UK).

Fair enough, you might say. But have you seen Fox News? Don’t all sorts of news organisations bend the truth to fit their agenda? There’s a case to be made, but there’s also a crucial difference. RT is funded and controlled by the Kremlin and is on a mission; a mission outlined in a new report by The Interpreter, part of the Institute of Modern Russia (disclosure: Index on Censorship has on occassion crossposted content from The Interpreter).

“The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money” elucidates what we had already long suspected: the Soviet Union may be dead, but Soviet tactics remain. And while the west may not want to believe it is in conflict with Russia, the Russians are already acting like it is (witness reports of heightened Russian air force activity in and near Nato airspace).

The report’s authors, Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev, describe disinformation techniques dating back to the Soviet era: straight propaganda, certainly, but also Dezinformatsiya — the planting of false stories to undermine confidence in western governments. These include alleged coup plots, the bizarre theory that AIDS was created by the CIA, even the suggestion that the assassination of Kennedy was an inside job.

The suggestion is that democracy is a sham, and that democratic governments are at best hypocrites and at worst constantly, deliberately acting against the interests of their own populations.

The best false stories always have a ring of truth and a ring of empathy. Many politicians are hypocrites, some politicians act against the interests of those they should represent. If this much is true, is it that much of a leap to imagine that the entire system is a crock? That democracy and human rights are empty terms? We’re just asking legitimate questions, as every conspiracy theorist ever has said at some point.

Conspiracy theorists find a home at RT. Presenter Abby Martin, for example, who briefly won praise for apparently criticising Russia’s actions in Ukraine, says she still has “many questions” (just asking questions!) about the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, and has used her show to expound on “false flag” attacks, alleged Israeli eugenics, and every US conspiracy theorists’ favourite, the massacre in Waco, Texas of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian cult in 1993.

All this would mean nothing if RT didn’t have a willing audience in the UK, the US and beyond. But a combination of a large budget, photogenic presenters and a certain way with a YouTube clip makes RT a serious player. It never quite veers into the straight out lunacy of Iran’s Press TV, which is quite open about its conspiracist contributors, and it looks like a serious operation. Furthermore, its positioning as an “alternative news source”, albeit one controlled by an increasingly authoritarian, paranoid and erratic Russian state, finds it fans among people who would rail against their own liberal states and societies (on the two occasions I visited the Occupy St Paul’s encampment in London, Russia Today was playing on a large screen there). All the while, the autocratic Putin is strengthened as democracy in undermined worldwide (witness how easily Putin was able to put the kibosh on effective intervention against Syria’s Assad through the relentless repetition of the line that helping the opposition would mean helping jihadist terrorists).

So what, as Lenin himself once asked, is to be done? After reports of UK broadcast regulator Ofcom’s recent investigations into RT for bias earlier this week, some people saw a chance to get RT taken off the air just weeks after it had begun. But this impulse is too close to political censorship in principle, and in practice, an ineffective sanction against a force that has huge power online, with millions upon millions of YouTube hits.

Decent democrats that they are, Weiss and Pomerantsev suggest eternal vigilance is required: we must be able to combat RT’s half truths and insinuations effectively, with hard facts and hard arguments, in order to stop them spreading. As ever, when arguments for counterspeech as the best defence against poison is suggested, one remembers Yeats’s lines: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

But this time 25 years ago, as East and West Germans embraced on top of the Berlin Wall, the world showed that the right argument can win even against the very worst. The Kremlin is playing the same games now as it did in its darkest days. Democrats should be ready to fight back.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]