Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

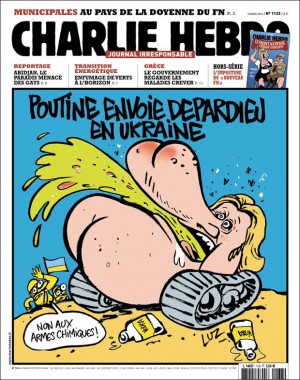

On the anniversary of the brutal attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to the defence of the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that some may consider offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack, which left 11 dead and 12 wounded, was a horrific reminder of the violence to which journalists, artists and other critical voices are subjected in a global atmosphere marked by increasing intolerance of dissent. The killings inaugurated a year that has proved especially challenging for proponents of freedom of opinion.

Non-state actors perpetrated violence against their critics largely with impunity, including the brutal murders of four secular bloggers in Bangladesh by Islamist extremists, and the killing of an academic, M M Kalburgi, who wrote critically against Hindu fundamentalism in India.

Despite the turnout of world leaders on the streets of Paris in an unprecedented display of solidarity with free expression following the Charlie Hebdo murders, artists and writers faced intense repression from governments throughout the year. In Malaysia, cartoonist Zunar is facing a possible 43-year prison sentence for alleged ‘sedition’; in Iran, cartoonist Atena Fardaghani is serving a 12-year sentence for a political cartoon; and in Saudi Arabia, Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for the views he expressed in his poetry.

Perhaps the most far-reaching threats to freedom of expression in 2015 came from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries including France, Britain and Germany issued a statement in which they called on Internet service providers to identify and remove online content ‘that aims to incite hatred and terror.’ In July, the French Senate passed a controversial law giving sweeping new powers to the intelligence agencies to spy on citizens, which the UN Human Rights Committee categorised as “excessively broad”.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the State. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On the anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, we, the undersigned, call on all Governments to:

PEN International

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian Association of Journalists

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Bytes for All

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Comité por la Libre Expresión – C-Libre

Committee to Protect Journalists

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

Freedom Forum

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión – IPLEX

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad de Venezuela

International Federation of Journalists

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Maharat Foundation

MARCH

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Foundation for West Africa

National Union of Somali Journalists

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

Reporters Without Borders

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters – AMARC

PEN Mali

PEN Kenya

PEN Nigeria

PEN South Africa

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Zambia

PEN Afrikaans

PEN Ethiopia

PEN Lebanon

Palestinian PEN

Turkish PEN

PEN Quebec

PEN Colombia

PEN Peru

PEN Bolivia

PEN San Miguel

PEN USA

English PEN

Icelandic PEN

PEN Norway

Portuguese PEN

PEN Bosnia

PEN Croatia

Danish PEN

PEN Netherlands

German PEN

Finnish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

Slovenian PEN

PEN Suisse Romand

Flanders PEN

PEN Trieste

Russian PEN

PEN Japan

Femen activists demonstrate in front of the Saudi Arabian embassy in Berlin. Photo: Florian Schuh/dpa/Alamy Live News

Societies often endanger lives by creating taboos, rather than letting citizens openly discuss stigmas and beliefs. Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our taboo-themed issue, which looks at no-go subjects worldwide, from abortion and mental health to the Holocaust and homosexuality

Teenager Rahenaz Sayed was told by her family not to sit on a bed, not to touch her hair oil and not to pray during her period.

Sayed, now 20, has started to go into schools in Mumbra, near Mumbai, along with two other young women, to discuss the taboos around menstruation, according to India’s Hindustan Times.

Traditionally, girls here didn’t talk to their mothers about getting their periods, or pain that they might be experiencing. This was something you were not expected to discuss, better, in fact, to pretend that it just wasn’t happening.

These restrictions were not open to challenge, until now. “We thought, ‘Why not talk of an issue which women don’t speak about and suffer silently?’ We suffered due to silences surrounding menstruation and didn’t want others to go through the same,” Mubhashirin Naik, one of the women starting to go into schools to talk about these long-held practices, told the newspaper.

They had been told that these “rules” came from the scriptures, but when they read those same passages themselves they found that while they spoke about women resting during menstruation nothing was written about banning them from prayer.

Taboos, subjects that are off limits to argument, are different in every country around the world. But this story shows why the act of not allowing a group of people to discuss a tradition or convention can injure society. Why should girls be treated like outcasts once a month and banned from doing the most normal things in life? The answer is because somehow this has become accepted and challenges frowned upon.

Once these three young women began to see that the structures they were being told to follow were nonsensical (they were not able to ask for painkillers, for instance), they had the strength to stand up against them. And by doing so, they will have begun to change the dynamic. No doubt, other women will also be encouraged to question the “rules”. And that’s how societies adapt over time, by questioning power.

In El Salvador, where abortion is illegal under any circumstance, even where the pregnant woman could die, the way that the law is enforced means that women who suffer a miscarriage can wake up with a police officer standing next to them.

The abortion law is so draconian that women who lose their baby through illness can find themselves charged with man- slaughter. Under the ferocity of this law, many women are too frightened to talk to anyone about any concerns they might have about pregnancy, let alone discuss abortion (more on this in the latest issue). In 2008 a 25-year-old woman, Guadalope Vásquez, was sentenced under the abortion law to a 30-year sentence after suffering a miscarriage. Under these conditions, women are often too frightened to discuss anything about health complications during their pregnancy with a doctor, or anyone else. Lives will be put at risk.

Throughout history, taboos have been established to limit and control society, and help to retain a status quo. “Best not mention it” is the nodded instruction to put something off limits in the family living room. In the 20th century, in the UK, societal disapproval would be rained down on those who ate something other than fish on Fridays, or children who played outside on a Sunday, or an adult who didn’t wear a hat to church. And in the US today the Westboro Baptist Church tells its female followers that it is forbidden for them to cut their hair. But why? Who decided these were the rules, and how do they change?

Sometimes it takes a generational shift, such as we have seen in Ireland, with the 62% vote to change the law to allow same-sex marriage. There’s a tipping point when a body of resistance builds up to such a point that the dam breaks and the public suddenly demands another way is found, and an older way is discarded.

But societal disapproval can be fierce and individuals who deviate from “the normal” can also find themselves isolated and alone, as Palestinian academic Mohammed Dajani Daoudi discovered when he took a group of his students to Auschwitz to learn about the Holocaust (read his story in the magazine). Dajani felt it was important for his university students to learn about this period of history. He saw his duty as one of teaching about,

not ignoring, a particular piece of history. Others saw it as the action of a traitor, accusing him of ignoring the suffering of Palestinians. He knew he was tackling a taboo subject, but hadn’t expected the reaction to the visit to be so violent. Afterwards he received death threats, and has now moved his family to Washington DC, partly for safety reasons.

Societies often endanger lives by creating taboos, rather than letting citizens openly discuss stigmas and beliefs. Remember the days when people would fear being judged for admitting they had cancer and would not mention it in public? Alastair Campbell does, and draws parallels to attitudes to mental illness today. Such beliefs can lead to people failing to talk to doctors about symptoms because of embarrassment, and potentially leaving diagnosis too late. These societal barriers are often out-of-date, sometimes stemming from archaic religious beliefs, or from traditions that have been left unchallenged. But still today an action that conflicts with expected behaviour can result in damage to an individual. The Encyclopedia Britannica states: “Generally, the prohibition that is inherent in a taboo includes the idea that its breach or defiance will be followed by some kind of trouble to the offender, such as lack of success in hunting or fishing, sickness, miscarriage, or death.” Living in fear of breaching such a “rule” can leave people afraid to dispute or argue for a sensible alternative.

To challenge a famous phrase from a WWI poster, talk doesn’t cost lives, but not talking certainly can.

Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What can’t people talk about? The latest magazine looks at taboos around the world”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”60px”][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: WHAT’S THE TABOO? ” css=”.vc_custom_1483453507335{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

We, the undersigned organisations, all dedicated to the value of creative freedom, are writing to express our grave concern that Ashraf Fayadh has been sentenced to death for apostasy.

Ashraf Fayadh, a poet, artist, curator, and member of British-Saudi art organisation Edge of Arabia, was first detained in August 2013 in relation to his collection of poems Instructions Within following the submission of a complaint to the Saudi Committee for the Promotion of Virtue. He was released on bail but rearrested in January 2014.

According to court documents, in May 2014 the General Court of Abha found proof that Fayadh had committed apostasy (ridda) but had repented for it. The charge of apostasy was dropped, but he was nevertheless sentenced to four years in prison and 800 lashes in relation to numerous charges related to blasphemy.

At Ashraf Fayadh’s retrial in November 2015 the judge reversed the previous ruling, declaring that repentance was not enough to avoid the death penalty. We believe that all charges against him should have been dropped entirely, and are appalled that Fayadh has instead been sentenced to death for apostasy, simply for exercising his rights to freedom of expression and freedom of belief.

As a member of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), the pre-eminent intergovernmental body tasked with protecting and promoting human rights, and the Chair of the HRC’s Consultative Group, Saudi Arabia purports to uphold and respect the highest standards of human rights. However, the decision of the court is a clear violation of the internationally recognised rights to freedom of conscience and expression. Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states that, “[e]veryone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief”. Furthermore, under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. Saudi Arabia is therefore in absolute contravention of the rights that as a member of the UN HRC it has committed to protect.

There are also widespread concerns over an apparent lack of due process in the trial: Fayadh was denied legal representation, reportedly as a result of his ID having been confiscated following his arrest in January 2014. It is our understanding that Fayadh has 30 days to appeal this latest ruling, and we urge the authorities to allow him access to the lawyer of his choice.

We call on the Saudi authorities to release Ashraf Fayadh and others detained in Saudi Arabia in violation of their right to freedom of expression immediately and unconditionally.

List of signatories:

AICA (International Association of Art Critics)

Algerian PEN

All-India PEN

Amnesty International UK

Arterial Network

ARTICLE 19

Artists for Palestine UK

Austrian PEN

Banipal

Bangladesh PEN

Bread and Roses TV

British Humanist Association

Bulgarian PEN

Centre for Secular Space

CIMAM (International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art)

Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain

Croatian PEN

Crossway Foundation

Danish PEN

English PEN

Ethiopian PEN-in-Exile

FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights)

Five Leaves Publications

Freemuse

German PEN

Haitian PEN

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

International Humanist and Ethical Union

Iranian PEN in Exile

Jimmy Wales Foundation

Lebanese PEN

Ledbury Poetry Festival

Lithuanian PEN

Modern Poetry in Translation

National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC)

Norwegian PEN

One Darnley Road

One Law for All

Palestinian PEN

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN South Africa

Peruvian PEN

Peter Tatchell Foundation

Portuguese PEN

Québec PEN

Russian PEN

San Miguel PEN

Scottish PEN

Slovene PEN

Society of Authors

South African PEN

Split This Rock

Suisse Romand PEN

School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, University of East Anglia

The Voice Project

Trieste PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru