9 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Magazine, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What is the state of academic freedom in 2015? Index on Censorship magazine’s summer 2015 issue takes a global vantage point to explore all the current threats – governmental, economic and social – faced by students, teachers and academics. “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

In the UK and US, offence and extremism are being used to shut down debates, prompting the adoption of “no-platforming” and “trigger-warnings”. In Turkey, an exam question relating to the Kurdish movement led to death threats for one historian. In Ireland, there are concerns over the restraints of corporate-sponsored research. In Mexico, students are being abducted and protests quashed.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”66714″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Plus we have reports on Ukraine, China and Belarus, on how education is expected to toe an official line. Also in this issue: Sir Harold Evans, AC Grayling, Tom Holland and Xinran present their free-speech heroes. Ken Saro-Wiwa Junior introduces a previously unpublished letter from his activist father, 20 years after he was executed by the Nigerian state, and Raymond Joseph reports on the dangers faced by Africa’s environmental journalists today. Comedian Samm Farai Monro, aka Comrade Fatso, looks at the rise of Zimbabwean satire; Matthew Parris interviews former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve; Italian journalist Cristina Marconi speaks to Marina Litvinienko, wife of the murdered KGB agent Alexander; and Konstanty Gebert looks at why the Polish Catholic church is upset by Winnie the Pooh and his non-specific gender.

Our culture section presents exclusive new short stories by exiled writers Hamid Ismailov (Uzbekistan) and Ak Welaspar (Turkmenistan), and poetry by Musa Okwonga and Angolan journalist Rafael Marques de Morais. Plus there’s artwork from Martin Rowson, Bangladeshi cartoonist Tanmoy and Eva Bee, and a cover by Ben Jennings.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: FIRED, THREATENED AND IMPRISONED” css=”.vc_custom_1483456198790{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Is academic freedom being eroded?

Silence on campus – Kaya Genç explores why a Turkish historian received death threats for writing an exam question

Universities under fire in Ukraine’s war – Tatyana Malyarenko unveils how Ukrainian scholars have to prove their patriotism in front of a special committee

Industrious academics – Michael Foley looks at how the commercial pressures on Ireland’s universities and students is narrowing research

Stifling freedom – Mark Frary’s take on 1oo years of attacks on US academic freedom

Ideas under review – Lawyer and journalist Suhrith Parthasarathy looks at how the Indian government interfering with universities’ autonomy. Also Meena Vari asks if India’s most creative artistic minds are being stifled

Girls standing up for education – Three young women from Pakistan, Uganda and Nigeria on why they are fighting for equality in classrooms

Open-door policy – Professor Thomas Docherty examines the threats to free speech in UK universities. Plus the student’s view, via the editor of Cambridge’s The Tab new site

Mexican stand-off – After the abduction of 43 students, Guadalajara-based journalist Duncan Tucker looks at the aftermath and the wider picture

Return of the red guards – Jemimah Steinfeld reports on the risks faced by students and teachers who criticise the government in China

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Pride and principles – Matthew Parris in conversation with the former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve

A letter from Ken Saro-Wiwa – A moving tribute from the son of one of the Ogoni nine and a previously unpublished letter from his father who was killed in Nigeria 20 years ago

Hunt and trap – Raymond Joseph reports on the dangers currently being faced by Africa’s environmental journalists

Litvinienko’s legacy – Italian journalist Cristina Marconi speaks to Marina Litvinienko, wife of the murdered KGB agent Alexander

God complex – Konstanty Gebert looks at why the Polish Catholic church is so worried about Winnie the Pooh’s gender

Zuma calls media ‘unpatriotic’ – Professor Anton Harber speaks to Natasha Joseph about the increasing political pressure on South African journalism

Dangers of blogging in Bangladesh – Vicky Baker on the recent murders of Bangladeshi bloggers by fundamentalists, plus a cartoon by Dhaka Tribune’s Tanmoy

Comedy of terrors – Samm Farai Monro, aka Comrade Fatso, on the power of Zimbabwe’s comedians to take on longstanding political taboos

Print under pressure – Miriam Mannak reports on the difficulties facing the media in Botswana, as the president tightens his grip on power

On forgotten free speech heroes – Sir Harold Evans, AC Grayling, Tom Holland and Xinran each pick an individual who has made a telling contribution to free speech today

Head to head – Lawyer Emily Grannis debates with Michael Halpern on whether academic’s emails should be in the public domain

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The pain of exile – Exclusive new fiction from Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov, who has not only had all his books banned back in his homeland, but every mention of his name

Eye of the storm – A poem by Musa Okwonga on the importance of allowing offensive views to be heard and debated on university campuses

The butterfly effect – The lesser known poetry of Index award-winner Rafael Marques De Morais

Listening to a beating heart – A new short story from Ak Welsapar, an author forced to flee his native Turkmenistan after being declared an enemy of the people

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg on the difficulties of measuring silenced voices

Index around the world – An update on Index’s latest work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Battle of the bots – Vicky Baker reports on the fake social media accounts trying to silence online protest

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 May 2014 | News

A London protest calling for the release of jailed Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt (Image: Index on Censorship)

Press freedom is at a decade low. Considering just a handful of the events of the past year — from Russian crackdowns on independent media and imprisoned journalists in Egypt, to press in Ukraine being attacked with impunity and government reactions to reporting on mass surveillance in the UK — it is not surprising that Freedom House have come to this conclusion in the latest edition of their annual press freedom report. This serves as a stark reminder that press freedom is a right we need to work continuously and tirelessly to promote, uphold and protect — both to ensure the safety of journalists and to safeguard our collective right to information and ability to hold those in power to account. On the eve of World Press Freedom day, we look back at some of the threats faced by the world’s press in the last 12 months.

1) Journalism is not terrorism…

National security has been used as an excuse to crack down on the press this year. “Freedom of information is too often sacrificed to an overly broad and abusive interpretation of national security needs, marking a disturbing retreat from democratic practices,” say Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in their recently released 2014 Press Freedom Index.

Journalists have faced terrorism and national security-related accusations in places known for their somewhat chequered relationship with press freedom, including Ethiopia and Egypt. However, the US and the UK, which have long prided themselves on respecting and protecting civil liberties, have also come under criticism for using such tactics — especially in connection to the ongoing revelations of government-sponsored mass surveillance.

American authorities have gone after former NSA contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden, tapped the phones of Associated Press staff, and demanded that journalists, like James Risen, reveal their sources. British authorities, meanwhile, detained David Miranda under the country’s Terrorism Act. Miranda is the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who broke the mass surveillance story. Authorities also raided the offices of the Guardian — a paper heavily involved in reporting in the Snowden leaks.

2) …but governments still like putting journalists in prison

The Al Jazeera journalists detained in Egypt on terrorism-related charges was one of the biggest stories on attacks on press freedom this year. However, Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed, Peter Greste and their colleagues are far from the only journalists who will spend World Press Freedom Day behind bars. The latest prison census from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) put the number of journalists in jail for doing their job at 211 — their second highest figure on record.

In Bahrain, award-winning photographer Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced in March to ten years in prison. In Uzebekistan, Muhammad Bekjanov, editor of opposition paper Erk, is serving a 19-year sentence — which was increased from 15 in 2012, just as he was due to be released. In Turkey, after waiting seven years, Fusün Erdoğan, former general manager of radio station Özgür Radyo, was last November sentenced to life in jail. Just last Friday, Ethiopian authorities arrested prominent political journalist Tesfalem Waldyes and six bloggers and activists.

3) New media is under attack…

As more journalism is being conducted online, blogs, social and other new media are increasingly being targeted in the suppression of press freedom. Almost half of the world’s jailed journalists work for online outlets, according to the CPJ. China — with its massive censorship apparatus — has continued censoring microblogging site Sina Weibo, while also turning its attention to relative newcomer WeChat. In March, it closed down several popular accounts, including that of investigative journalist Luo Changping.

Meanwhile, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has publicly all but declared war on social media, at one point calling it the “worst menace to society”. Twitter played a big role in last summer’s Gezi Park protests, used by journalists and other protesters alike. Only days ago, Turkish journalist Önder Aytaç was jailed, essentially, because of the letter “k” in a Tweet.

Meanwhile Russia has seen a big crackdown on online news outlets, while legislation recently passed in the Duma is targeting blogs and social media.

4) …and independent media continues to struggle

Only one in seven people in the world live in countries with free press. In many parts of the world, mainstream media is either under tight control by the government itself or headed up media moguls with links to those in power, with dissenting voices within news organisation often being pushed out. Brazil, for instance, has been labelled “the country of 30 Berlusconis” because regional media is “weakened by their subordination to the centres of power in the country’s individual states”. At the start of the year, RIA Novosti — known for on occasion challenging Russian authorities — was liquidated and replaced by the more Kremlin-friendly Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today), while in Montenegro, has seen efforts by the government to cut funding to critical media. This is not even mentioning countries like North Korea and Uzbekistan, languishing near the bottom of press freedom ratings, where independent journalism is all but non-existent.

5) Attacks on journalists often go unpunished

A staggering fact about the attacks on journalists around the world, is how many happen with impunity. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed. Most of the perpetrators of those crimes have not been brought to justice. Attacks can be orchestrated by authorities or by non-state actors, but the lack of adequate responses by those in power “fuels the cycle of violence against news providers,” says RSF. In Mexico, a country notorious for violence against the press, three journalists were murdered in 2013. By last October, the state public prosecutor’s office had yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. Syria, with its ongoing, devastating war, is the deadliest place in the world to be a journalist, while some of the attacks on press during the conflict in Ukraine, have also taken place without perpetrators being held accountable. That attacks in the country appear to be accelerating, CPJ say is “a direct result of the impunity with which previous attacks have taken place”.

This article was published on May 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | Egypt, Iraq, News, Nigeria, Pakistan, Religion and Culture, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam

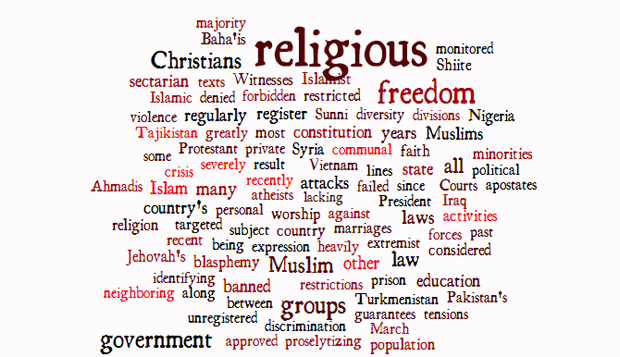

In January, Index summarised the U.S. State Department’s “Countries of Particular Concern” — those that severely violate religious freedom rights within their borders. This list has remained static since 2006 and includes Burma, China, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan. These countries not only suppress religious expression, they systematically torture and detain people who cross political and social red lines around faith.

Today the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent watchdog panel created by Congress to review international religious freedom conditions, released its 15th annual report recommending that the State Department double its list of worst offenders to include Egypt, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Syria.

Here’s a roundup of the systematic, ongoing and egregious religious freedom violations unfolding in each.

1. Egypt

The promise of religious freedom that came with a revised constitution and ousted Islamist president last year has yet to transpire. An increasing number of dissident Sunnis, Coptic Christians, Shiite Muslims, atheists and other religious minorities are being arrested for “ridiculing or insulting heavenly religions or inciting sectarian strife” under the country’s blasphemy law. Attacks against these groups are seldom investigated. Freedom of belief is theoretically “absolute” in the new constitution approved in January, but only for Muslims, Christians and Jews. Baha’is are considered apostates, denied state identity cards and banned from engaging in public religious activities, as are Jehovah’s Witnesses. Egyptian courts sentenced 529 Islamist supporters to death in March and another 683 in April, though most of the March sentences have been commuted to life in prison. Courts also recently upheld the five-year prison sentence of writer Karam Saber, who allegedly committed blasphemy in his work.

2. Iraq

Iraq’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but the government has largely failed to prevent religiously-motivated sectarian attacks. About two-thirds of Iraqi residents identify as Shiite and one-third as Sunni. Christians, Yezidis, Sabean-Mandaeans and other faith groups are dwindling as these minorities and atheists flee the country amid discrimination, persecution and fear. Baha’is, long considered apostates, are banned, as are followers of Wahhabism. Sunni-Shia tensions have been exacerbated recently by the crisis in neighboring Syria and extremist attacks against religious pilgrims on religious holidays. A proposed personal status law favoring Shiism is expected to deepen divisions if passed and has been heavily criticized for allowing girls to marry as young as nine.

3. Nigeria

Nigeria is roughly divided north-south between Islam and Christianity with a sprinkling of indigenous faiths throughout. Sectarian tensions along these geographic lines are further complicated by ethnic, political and economic divisions. Laws in Nigeria protect religious freedom, but rule of law is severely lacking. As a result, the government has failed to stop Islamist group Boko Haram from terrorizing and methodically slaughtering Christians and Muslim critics. An estimated 16,000 people have been killed and many houses of worship destroyed in the past 15 years as a result of violence between Christians and Muslims. The vast majority of these crimes have gone unpunished. Christians in Muslim-majority northern states regularly complain of discrimination in the spheres of education, employment, land ownership and media.

4. Pakistan

Pakistan’s record on religious freedom is dismal. Harsh anti-blasphemy laws are regularly evoked to settle personal and communal scores. Although no one has been executed for blasphemy in the past 25 years, dozens charged with the crime have fallen victim to vigilantism with impunity. Violent extremists from among Pakistan’s Taliban and Sunni Muslim majority regularly target the country’s many religious minorities, which include Shiites, Sufis, Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Baha’is. Ahmadis are considered heretics and are prevented from identifying as Muslim, as the case of British Ahmadi Masud Ahmad made all too clear in recent months. Ahmadis are politically disenfranchised and Hindu marriages are not state-recognized. Laws must be consistent with Islam, the state religion, and freedom of expression is constitutionally “subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam,” fostering a culture of self-censorship.

5. Tajikistan

Religious freedom has rapidly deteriorated since Tajikistan’s 2009 religion law severely curtailed free exercise. Muslims, who represent 90 percent of the population, are heavily monitored and restricted in terms of education, dress, pilgrimage participation, imam selection and sermon content. All religious groups must register with the government. Proselytizing and private religious education are forbidden, minors are banned from participating in most religious activities and Muslim women face many restrictions on communal worship. Jehovah’s Witnesses have been banned from the country since 2007 for their conscientious objection to military service, as have several other religious groups. Hundreds of unregistered mosques have been closed in recent years, and “inappropriate” religious texts are regularly confiscated.

6. Turkmenistan

The religious freedom situation in Turkmenistan is similar to that of Tajikistan but worse due to the country’s extraordinary political isolation and government repression. Turkmenistan’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but many laws, most notably the 2003 religion law, contradict these provisions. All religious organizations must register with the government and remain subject to raids and harassment even if approved. Shiite Muslim groups, Protestant groups and Jehovah’s Witnesses have all had their registration applications denied in recent years. Private worship is forbidden and foreign travel for pilgrimages and religious education are greatly restricted. The government hires and fires clergy, censors religious texts, and fines and imprisons believers for their convictions.

7. Vietnam

Vietnam’s government uses vague national security laws to suppress religious freedom and freedom of expression as a means of maintaining its authority and control. A 2005 decree warns that “abuse” of religious freedom “to undermine the country’s peace, independence, and unity” is illegal and that religious activities must not “negatively affect the cultural traditions of the nation.” Religious diversity is high in Vietnam, with half the population claiming some form of Buddhism and the rest identifying as Catholic, Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, Protestant, Muslim or with other small faith and non-religious communities. Religious groups that register with the government are allowed to grow but are closely monitored by specialized police forces, who employ violence and intimidation to repress unregistered groups.

8. Syria

The ongoing Syrian crisis is now being fought along sectarian lines, greatly diminishing religious freedom in the country. President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, aligned with Hezbollah and Shabiha, have targeted Syria’s majority-Sunni Muslim population with religiously-divisive rhetoric and attacks. Extremist groups on the other side, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), have targeted Christians and Alawites in their fight for an Islamic state devoid of religious tolerance or diversity. Many Syrians choose their allegiances based on their families’ faith in order to survive. It’s important to note that all human rights, not just religious freedom, are suffering in Syria and in neighboring refugee camps. In quieter times, proselytizing, conversion from Islam and some interfaith marriages are restricted, and all religious groups must officially register with the government.

This article was originally posted on April 30, 2014 at Religion News Service

15 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Beyond its near neighbourhood, the EU works to promote freedom of expression in the wider world. To promote freedom of expression and other human rights, the EU has 30 ongoing human rights dialogues with supranational bodies, but also large economic powers such as China.

The EU and freedom of expression in China

The focus of the EU’s relationship with China has been primarily on economic development and trade cooperation. Within China some commentators believe that the tough public noises made by the institutions of the EU to the Chinese government raising concerns over human rights violations are a cynical ploy so that EU nations can continue to put financial interests first as they invest and develop trade with the country. It is certainly the case that the member states place different levels of importance on human rights in their bilateral relationships with China than they do in their relations with Italy, Portugal, Romania and Latvia. With China, member states are often slow to push the importance of human rights in their dialogue with the country. The institutions of the European Union, on the other hand, have formalised a human rights dialogue with China, albeit with little in the way of tangible results.

The EU has a Strategic Partnership with China. This partnership includes a political dialogue on human rights and freedom of the media on a reciprocal basis.[1] It is difficult to see how effective this dialogue is and whether in its present form it should continue. The EU-China human rights dialogue, now 14 years old, has delivered no tangible results.The EU-China Country Strategic Paper (CSP) 2007-2013 on the European Commission’s strategy, budget and priorities for spending aid in China only refers broadly to “human rights”. Neither human rights nor access to freedom of expression are EU priorities in the latest Multiannual Indicative Programme and no money is allocated to programmes to promote freedom of expression in China. The CSP also contains concerning statements such as the following:

“Despite these restrictions [to human rights], most people in China now enjoy greater freedom than at any other time in the past century, and their opportunities in society have increased in many ways.”[2]

Even though the dialogues have not been effective, the institutions of the EU have become more vocal on human rights violations in China in recent years. For instance, it included human rights defenders, including Ai Weiwei, at the EU Nobel Prize event in Beijing. The Chinese foreign ministry responded by throwing an early New Year’s banquet the same evening to reduce the number of attendees to the EU event. When Ai Weiwei was arrested in 2011, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton issued a statement in which she expressed her concerns at the deterioration of the human rights situation in China and called for the unconditional release of all political prisoners detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression.[3] The European Parliament has also recently been vocal in supporting human rights in China. In December 2012, it adopted a resolution in which MEPs denounced the repression of “the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, press freedom and the right to join a trade union” in China. They criticised new laws that facilitate “the control and censorship of the internet by Chinese authorities”, concluding that “there is therefore no longer any real limit on censorship or persecution”. Broadly, within human rights groups there are concerns that the situation regarding human rights in China is less on the agenda at international bodies such as the Human Rights Council[4] than it should be for a country with nearly 20% of the world’s population, feeding a perception that China seems “untouchable”. In a report on China and the International Human Rights System, Chatham House quotes a senior European diplomat in Geneva, who argues “no one would dare” table a resolution on China at the HRC with another diplomat, adding the Chinese government has “managed to dissuade states from action – now people don’t even raise it”. A small number of diplomats have expressed the view that more should be done to increase the focus on China in the Council, especially given the perceived ineffectiveness of the bilateral human rights dialogues. While EU member states have shied away from direct condemnation of China, they have raised freedom of expression abuses during HRC General Debates.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy and human rights dialogues

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is the agreed foreign policy of the European Union. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 allowed the EU to develop this policy, which is mandated through Article 21 of the Treaty of the European Union to protect the security of the EU, promote peace, international security and co-operation and to consolidate democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedom. Unlike most EU policies, the CFSP is subject to unanimous consensus, with majority voting only applying to the implementation of policies already agreed by all member states. As member states still value their own independent foreign policies, the CFSP remains relatively weak, and so a policy that effectively and unanimously protects and promotes rights is at best still a work in progress. The policies that are agreed as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy therefore be useful in protecting and defending human rights if implemented with support. There are two key parts of the CFSP strategy to promote freedom of expression, the External Action Service guidelines on freedom of expression and the human rights dialogues. The latter has been of variable effectiveness, and so civil society has higher hopes for the effectiveness of the former.

The External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines

As part of its 2012 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU is working on new guidelines for online and offline freedom of expression, due by the end of 2013. These guidelines could provide the basis for more active external policies and perhaps encourage a more strategic approach to the promotion of human rights in light of the criticism made of the human rights dialogues.

The guidelines will be of particular use when the EU makes human rights impact assessments of third countries and in determining conditionality on trade and aid with non-EU states. A draft of the guidelines has been published, but as these guidelines will be a Common Foreign and Security Policy document, there will be no full and open consultation for civil society to comment on the draft. This is unfortunate and somewhat ironic given the guidelines’ focus on free expression. The Council should open this process to wider debate and discussion.

The draft guidelines place too much emphasis on the rights of the media and not enough emphasis on the role of ordinary citizens and their ability to exercise the right to free speech. It is important the guidelines deal with a number of pressing international threats to freedom of expression, including state surveillance, the impact of criminal defamation, restrictions on the registration of associations and public protest and impunity against human right defenders. Although externally facing, the freedom of expression guidelines may also be useful in indirectly establishing benchmarks for internal EU policies. It would clearly undermine the impact of the guidelines on third parties if the domestic policies of EU member states contradict the EU’s external guidelines.

Human rights dialogues

Another one of the key processes for the EU to raise concerns over states’ infringement of the right to freedom of expression as part of the CFSP are the human rights dialogues. The guidelines on the dialogues make explicit reference to the promotion of freedom of expression. The EU runs 30 human rights dialogues across the globe, with the key dialogues taking place in China (as above), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Belarus. It also has a dialogues with the African Union, all enlargement candidate countries (Croatia, the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia and Turkey), as well as consultations with Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Russia. The dialogue with Iran was suspended in 2006. Beyond this, there are also “local dialogues” at a lower level, with the Heads of EU missions, with Cambodia, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Israel, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Vietnam. In November 2008, the Council decided to initiate and enhance the EU human rights dialogues with a number of Latin American countries.

It is argued that because too many of the dialogues are held behind closed doors, with little civil society participation with only low-level EU officials, it has allowed the dialogues to lose their importance as a tool. Others contend that the dialogues allow the leaders of EU member states and Commissioners to silo human rights solely into the dialogues, giving them the opportunity to engage with authoritarian regimes on trade without raising specific human rights objections.

While in China and Central Asia the EU’s human rights dialogues have had little impact, elsewhere the dialogues are more welcome. The EU and Brazil established a Strategic Partnership in 2007. Within this framework, a Joint Action Plan (JAP) covering the period 2012-2014 was endorsed by the EU and Brazil, in which they both committed to “promoting human rights and democracy and upholding international justice”. To this end, Brazil and the EU hold regular human rights consultations that assess the main challenges concerning respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law; advance human rights and democracy policy priorities and identify and coordinate policy positions on relevant issues in international fora. While at present, freedom of expression has not been prioritised as a key human rights challenge in this dialogue, the dialogues are seen by both partners as of mutual benefit. It is notable that in the EU-Brazil dialogue both partners come to the dialogues with different human rights concerns, but as democracies. With criticism of the effectiveness and openness of the dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states in the promotion of human rights with third countries and assess whether the dialogues can be improved.

[1] It covers both press freedom for the Chinese media in Europe and also press freedom for European media in China.

[2] China Strategy Paper 2007-2013, Annexes, ‘the political situation’, p. 11

[3] “I urge China to release all of those who have been detained for exercising their universally recognised right to freedom of expression.”

[4] Interview with European diplomat, February 2013.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]