3 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

I write to Long, asking him to remove his footnotes. The poor man is now the mouse in the middle, caught between an exigent author and equally demanding censors. As we descend into the fine points of Vietnamese history and geography, my editor and I embark on a voluminous correspondence. The nature of this correspondence is exemplified by Rung Sat, the Swamp of the Assassins, which is the first item that Long has tagged for a footnote.

Southeast of Saigon, bordering the city’s main shipping channel to the sea, Rung Sat is the tidal mangrove swamp that for many years was home to the Binh Xuyen river pirates. The French had used the river pirates to help manage their colonial operations in Vietnam. Bay Vien, head of the pirates, had been elevated to the rank of general and given Saigon to run as a personal fiefdom. He owned the Hall of Mirrors, the largest brothel in Asia, with twelve hundred employees. He ran the Grand Monde casino in Cholon and the Cloche d’Or casino in Saigon. Bay Vien’s lieutenant was named chief of police in the capitol region, which stretched sixty miles from Saigon to Cap Saint Jacques. Bay Vien’s most lucrative operation, with a share of the proceeds going to the French government, was the opium trade that stretched all the way from Laos to Marseille. The Swamp of the Assassins also served as a communist staging area during the Vietnam war, and the river pirates themselves had briefly doubled as communists, before they switched to the other side.

Before retiring to Paris, where he could be seen strolling down the Champs Elysees with his pet tiger on a leash, Bay Vien used to hide in the Rung Sat swamp when things got too hot in Saigon. This was the case in 1955, after legendary spook Edward Lansdale arrived in town. Intent on knocking the French from their colonial perch and replacing them with a client government loyal to the United States, Lansdale launched a military campaign against the Binh Xuyen. Vietnamese army troops fought the pirates house-to-house for control of Saigon. More soldiers were involved in this week-long battle than in the famous Tet Offensive of 1968. Five hundred people were killed, two thousand wounded, and another twenty thousand left homeless. This proxy battle between France and the United States marked the transition from the First Indochina War to the Second.

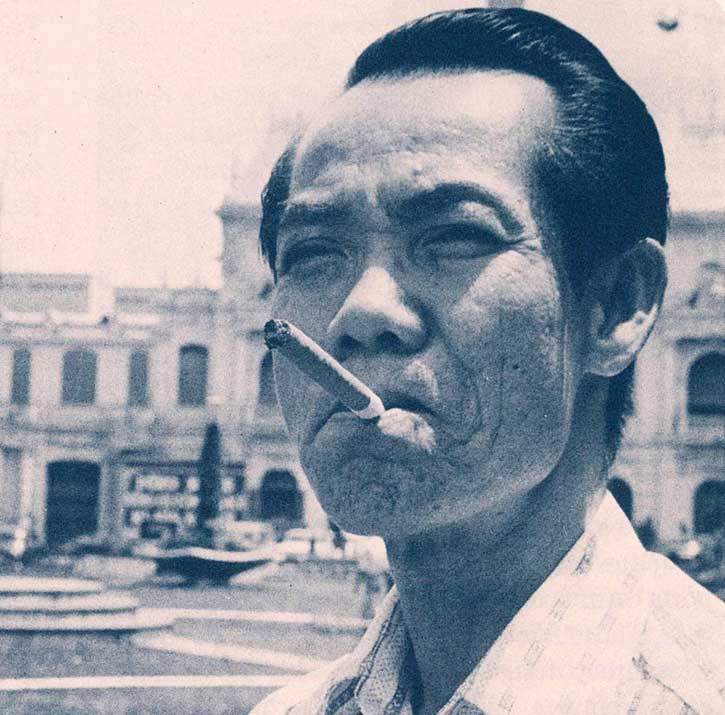

Pham Xuan An claimed that he learned everything he knew about spying from Edward Lansdale. Lansdale was An’s patron as he began his career in military intelligence, and it was Lansdale who recommended that An study journalism in the United States. Because of the Swamp’s importance for colonialists, communists, river pirates, and spies, I had done a lot of archival work to verify its position in Vietnamese history. This is why I was particularly displeased to find a footnote saying, “The author is wrong.”

It is not called Rung Sat but Rung Sac, said Long, thereby turning the Swamp of the Assassins into the Forest of Seacoast Shrubs. (Rung means forest, but when dealing with wet mangrove forests, one might plausibly call them swamps. Sat is a Sino-Vietnamese combining word meaning death, as in am sat, to assassinate.) The government has renamed the Swamp because the government says this was never its correct name. And why is this? Because the government maintains that south Vietnamese have been distorting the country’s language and inadvertently displaying their ignorance for centuries. Southerners pronounce words ending in “t” as if they ended in “k” or a hard “c.” Thus, Rung Sac mistakenly became Rung Sat because southerners can’t spell correctly and are often confused by two words that sound the same. Undoubtedly, the communist officials behind this renaming were also sensitive about having used Rung Sat as a staging area during the American war. They didn’t want to be confused with swamp-dwelling assassins.

The issue might plausibly have been resolved by saying that the area used to be called x and is now known as y. But Vietnamese censors don’t work this way. They have a totalizing view of history. They reach back through time to correct errors retroactively. Even in quoted speech, Bay Vien and Lansdale would be forced to talk about the forest of seacoast shrubs. One can imagine what kind of stilted prose this produces, as anachronisms and communist terminology are inserted into the historical record. I had no choice but to mount a campaign proving, “The editor is wrong.”

I send Long a variety of French and Vietnamese maps, including a 1955 Vietnamese map showing military operations against the Binh Xuyen river pirates. I send maps from U.S. Naval Operations in the area, a copy of President Richard Nixon’s citation to the Rung Sat Special Zone Patrol Group, and a 1974 U.S. Academy of Sciences research report on Rung Sat. I send a 2010 Google satellite map, with the area marked Rung Sat, and I even send a photo of a bus leaving Ho Chi Minh City, with its scheduled destination clearly marked as Rung Sat.

Long comes back with his own “proof and evidence,” including the web site for the Rung Sac Resort and Restaurant, and some real estate prospectuses for housing developments that are financed, I presume, by local Party officials. I press the argument through more emails, until Long eventually writes, “I agree to remove the footnote about Rung Sat entirely.” As we discuss the rest of the footnotes, Long and I return to fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature. Every email exchange becomes the Swamp of the Assassins Redux, until finally Long proposes “to remove wrong footnotes or footnotes concerning your mistakes,” I graciously accept his offer.

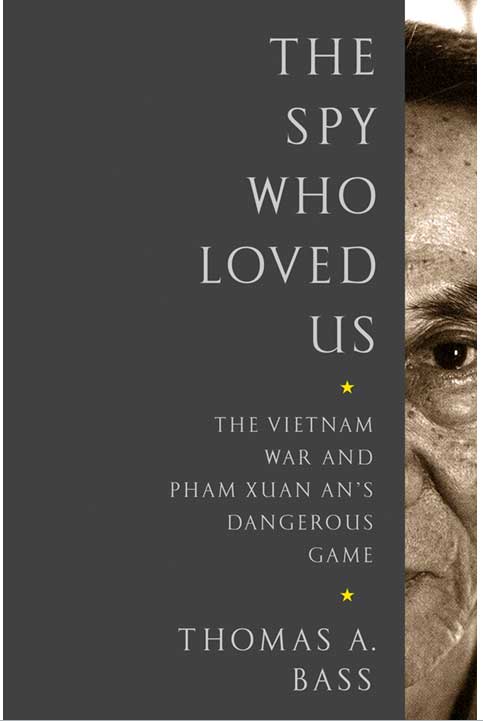

Next we turn to discussing the title of the book. “The Spy Who Loved Us” could be translated as “The Spy Who Loved America,” or, more poetically, as “America’s Best Enemy,” except that the censors reject these titles. As Long explains, “‘America’s Best Enemy’ is good, but somewhat sensitive. Why ‘best enemy’? Is this implying that Pham Xuan An was not entirely loyal to the revolutionary cause?” After further reflections on “the right viewpoint,” Long admits that “the issue proves to be more intricate than we initially thought.” Later I receive word that “The Spy Who Loved America” has been “immediately rejected” by Vietnam’s “publishing authorities.”

By this time, the people helping me review the manuscript (all of whom wish to remain anonymous) have compiled a list of phrases, sentences, and paragraphs that have been bowdlerized or pruned from the text. When I send this list to Long, he replies, “I assure you that the translator did not omit any sentences or paragraphs. He only highlighted sensitive phrases. The omissions or modifications are mine.”

In October 2010, Long writes to say that he is “tired of this project” and discouraged by having the book rejected by two state-owned publishing companies. He is trying to secure a publishing license from a third company, but people are telling him that the upcoming 11th Communist Party Congress, in the spring of 2011, makes it a “sensitive time” for publishing in Vietnam. This is a delicate moment “when everybody takes non-action to avoid complexities,” he says.

Writing to my agent in December 2010, Long says, “We understand the impatience of our author! But the situation is worse than you imagine. Another state-owned publisher has refused to issue a publishing license for our translation. Clearly, it is a highly-sensitive book at this moment in time. Everything is now hanging in the wind.”

When Long writes to tell me that another batch of publishers has refused to give him a license, I imagine the process as something akin to Random House having to clear a book through the Pentagon Publishing Company. If Pentagon Press won’t ink the deal, then Random has to go to publishing houses owned by Homeland Security or the FBI. These negotiations must be prolonged and humiliating, and, in a gift-giving culture like Vietnam, they must also be expensive.

I cool my heels through 2011, waiting for the Communist Party to shuffle a new set of rulers into place. In February 2012, I write to Long, wishing him a happy Water Dragon year and asking if he would kindly provide me with a list of all the governmental bodies that have so far been involved in censoring my book.

A month later, he writes back to apologize for being out of touch. He says he has left Nha Nam to go to work as an editor at a company that publishes math books for children. I feel a twinge of conscience, fearing that I might have been responsible for this change in jobs. “About the license to publish The Spy Who Loved Us,” he writes, “Nha Nam has been applying and still continues to apply to several publishers for a publishing license, not stopping at any time as you maybe think. I have asked for the latest information and was told that officials at Nha Nam still hope that the book will be published.”

“Officially, only state publishing houses are permitted to produce printed books,” Long explains. “So a privately-owned (non-state) company like Nha Nam must participate in so-called joint publication, in order to publish a book under the aegis of a state publishing house and pay a publication fee to this publishing house.”

“Technically, there is no censorship in Vietnam,” he says, “but directors or editors-in-chief of the publishing houses are sometimes required to remove sensitive items, or even are timid enough to let the book go unpublished (this is our case). This kind of action we call self-censorship, and it is the Gordian knot of the Vietnamese publishing industry.”

Long attaches to his email a copy of Vietnam’s Law on Publishing, a twenty-two-page document that does indeed say quite plainly, in Article 5.2, “The State shall not censor works prior to their publication.” The rest of the document is devoted to contradicting Article 5.2, as it enumerates what is “prohibited during publishing activities.” This includes “propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Article 10),” the incitement of war and aggression, the “spread of reactionary ideology, depraved life styles, cruel acts, social evils and superstition, or destruction of good morals and customs.” Other sections are devoted to the protection of Party, military, defense and other kinds of state secrets. Also forbidden is the “distortion of historical facts,” particularly those “opposing the achievement of the revolution.”

Long tells me that my new editor at Nha Nam is Ms. Nguyen Thi Thu Yen, who appears to be doing double duty as the person who negotiates foreign contracts. After our months of emailing back and forth, Long and I had prepared a second set of galleys, stripped of footnotes and corrected, at least as far as my advisors and I could push it. The manuscript is still bowdlerized and rewritten in dozens of places. All criticism of China has been removed. So too are any references to reeducation camps, graft, corruption, mistakes made by the Communist Party, and other “sensitive” subjects. Unfortunately, Long’s text will soon be supplanted by another, officially-licensed version. Again, I have misunderstood the nature of Vietnamese publishing. After all these months, my book has not yet been censored. It has undergone a kind of pre-censorship review, but the serious work of scrubbing sensitive material from the text has yet to begin.

Part 3: Hostage trade

This second installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 3, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Jul 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, United Kingdom

(Image: Shutterstock)

I’ve occasionally thought it might be fun, even therapeutic, to have an enemies list. I would carry it in my pocket, a single, increasingly ragged B5 ruled sheet, on which I would scribble, with my specially purchased green Bic biro, the names of those who had taken against me, or to whom I had taken against; starting with the Ayatollah Khamenei (long story) and ending, well, never ending.

I could scrawl and scrawl, adding people and organisations: the wine waiter who mysteriously sneered “For you sir, perhaps a glass of Merlot” (I know that’s an insult, I just don’t know why that’s an insult), everyone who stands on the bottom deck of a bus when there are seats upstairs, the Communist Party of Vietnam, and so on, endlessly, ‘til my little scrap of paper was a grand mess of green ink, letters over letters over letters, upside down, vertical, horizontal, furious underlines, multiple exclamation marks, sometimes, just discernible, the word “NO” in capital letters.

It would be good to have the list at hand, to have it under control, I imagine. As long as I’ve got them all written down, and the list is on my person, I won’t be caught off guard. This would not be odd, you agree. It would be an entirely reasonable thing to do in a world where foes stalk us, waiting to mug us, or make us look like mugs.

For politicians, this sense of the entire world waiting for the moment you mess up is amplified, partly because it is a reflection of the truth. Opposition activists will pick up on every word you say, and the slightest slip will be turned into a hilarious/earth-shatteringly dull meme in mere minutes, with earnest young women imploring people to retweet whatever the hell it was that proves you hate nurses/the nuclear family/your party leader, and proves you’re not fit to do XYZ.

And then there’s the “feral beasts” of the press, as Tony Blair famously referred to journalists in 2007 (this was literally worn as a badge of pride by many: the New Statesman’s then political editor had “Feral Beast” badges made, which he handed out to every journalist he met), who you spend your life trying to please while deep down knowing they are willing you to cock up. You really, really can’t win.

Faced with all this, it’s not surprising that politicians and politicos are a little wary of the world. But there is a difference between wariness and paranoia, a difference demonstrated by the reaction to the Sunday Times’s report of a speech delivered recently by Labour’s Jon Cruddas to the left-wing group Compass. An attendee of the publicly advertised meeting passed a recording of Cruddas’s comments to the Sunday Times. The journalist then had the temerity to report on the speech! According to the Telegraph’s Stephen Bush, Cruddas’s next appearance, at the Fabian Society Summer Conference, was “bad tempered” and full of attacks on the “‘herberts’ and ‘muppets’ of Fleet Street who might be listening to his every word or statement in search of a headline”.

Meanwhile Neal Lawson, Compass chairman and Cruddas’s host, wrote a strange article for the Guardian, suggesting, somehow, that Cruddas’s comments were not in the public interest, and somewhat hyperbolically claiming: “The Sunday Times got its cheap splash, but in the process our political culture is diminished, maybe fatally.”

Lawson then really went for it, claiming: “What happens next? We either accept that the Murdoch empire — and maybe others — make toxic yet another level of public life and succeed in shrivelling our body politic still further. Or we make whatever stand we can.

Their goal is not just to destroy Labour or even any alternative to the individualistic, me-first politics of the past 30 years. They want to destroy the possibility of such an alternative. Invading the spaces in which such an alternative is discussed, such as the Compass event, is just a means to an end.”

All this at first reads as merely silly, but there are a few strands in it that are quite worrying. The first is the idea that a journalist reporting on a public meeting (Lawson’s justification for claiming it was “semi-private” was that attendees had to register and there was no press list) is fatally undermining democracy. There is an authoritarian undertone to this: journalists should report on what we allow them to report, not what is of interest. This is also reflected in Lawson’s comment about journalistic practices — “For the papers who do this it’s an easy, cheap hit: no research, no digging, just someone with a smartphone who is willing to sit through boring meetings on a Saturday afternoon” — somehow the story is not a good one because it was gained through day-to-day processes rather than via the Woodward-And-Bernstein routines that are seen as “proper” “investigative” journalism.

Secondly, there is the Murdochophobia which escalates an agenda to a conspiracy: The Sunday Times and Murdoch’s other papers are broadly conservative, it is true, but that’s a long way from having a goal of “destroying Labour” (a party Murdoch’s papers supported for a long time).

The problem with this paranoid mindset is that nobody takes responsibility for their own actions or even their own opinions. The question of whether there is a problem with Labour policy or not, becomes simply evil newspaper versus innocent, naive, poor little politician. It is self-pitying and self-defeating. Either have the debate, or don’t. But don’t complain when reporters report.

This article was posted on July 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jun 2014 | News, Politics and Society

Index speaks at the IAPC meet 2014, Vienna

There has been an 18% rise in violence towards journalists compared to the same period last year, International Media Support, an organisation that works in many of the world’s biggest danger zones, told an international journalism conference.

News from Egypt – as three journalists from Al-Jazeera are sentenced to seven years in prison – demonstrates the huge threats that journalists can face. The subject was covered in detail at this year’s International Association of Press Clubs annual conference in Vienna, which Index on Censorship attended this month.

“Some countries we just can’t work in,” said John Barker from Media Legal Defence Initiative, who help represent journalists facing legal charges for reporting and presented on their work. “Every time we work in Vietnam, for example, the lawyers are arrested. In many places, we can’t transfer money to them.” Nonetheless, they are currently working on 102 cases in 39 countries.

Other topics for discussion included:

- The increasing number of freelancers working in danger zones – and with little training

- How to protect fixers, translators and local journalists

- Possible methods for funding legal representation (Crowdfunding worked as a recent experiment in Ethiopia, said MLDI)

The event was hosted by Austria’s PresseClub Concordia – said to be the oldest press club in the world (founded in 1859 – reformed in 1946, after having its assets seized by Nazis). It was attended by press clubs from around the world, including Poland, Belarus, Syria, the Czech Republic, the US, India, Ukraine, Mongolia, Germany, and Switzerland. Other NGOs – alongside Index, International Media Support and Media Legal Defence Initiative – included the International Press Institute and RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues).

Index was invited to present on the work the organisation is doing around the world, which included sharing the stories of our Freedom of Expression Awards winners and nominees, and news of our current work, including a crowdsourcing project to map media freedom violations across the EU. Plus we also shared stories from our quarterly magazine – including a report on violent threats to journalists in Tanzania and how news stories are getting out of Syria via citizen reports.

Index also hosted round-table discussion on censorship, which provoked an impassioned debate. One of the most interesting topics covered was on contracts that some journalists are being made to sign on what they can and can’t write. We heard of cases in Mongolia and Germany. We also discussed self-censorship and censorship by complying to advertisers’ will. One attendee from the Berlin Press Club said: “There is no censorship in Germany, but journalists feel like they have scissors in their heads. You have to self-censor before you write.” This is an area that we are researching, so please get in touch if you have experiences and examples.

The meeting also visited a new exhibition on censorship during WW1 and ended with the Concordia Press Club’s annual ball, which is a key fundraiser for the club and attended by over 2,000 guests. See photos from the event below.

This article was posted on June 24, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 May 2014 | India, News, Politics and Society

Nitin Gadkari, a politician with a chequered, if not dubious record of integrity and probity, had a political opponent arrested for slander. (Photo: Amit Kumar/Demotix)

Once, President Lyndon Johnson was caught in the crossfire of an anti-Vietnam war protest. A placard was shoved in his face: “LBJ pull out, like your daddy should have done.” Sure, LBJ got the pun, as would have Anthony Weiner in our present times, but he remained unperturbed. Consider Lady Violet Bonham Carter’s biting repartee to an irresolute Sir Stafford Cripps, saying he “has a brilliant mind — until it is made up”.

Mordant wit is what makes politics and political debates sparkle with brilliance, besides deflating windbags and putting stuffed shirts in their place. Even if the “sourcasm” is discounted, plainspeak and no-holds barred verbal duels contribute in no small measure to ensuring accountability, for who isn’t mortally petrified of lacerating criticism?

Turns out that in India, folks with brittle egos and skeletons stacked up in their closets, can and will wield the law to clam a critic’s mouth shut, and even have them put in jail. And this is irrespective of resorting to some risqué puns.

Arvind Kejriwal, founder of the Aam Aadmi (Common Man) Party, who is out on a limb to eradicate the scourge of corruption, realised this to his peril when Nitin Gadkari, a politician with a chequered, if not dubious record of integrity and probity, had him arrested for slander. Slander? No, Gadkari wasn’t invoking some law of the Middle Ages or the Victorian Era. He was merely invoking Sections 499 and 500 of the Indian Penal Code which criminalise defamation, both in writing as well as verbal statements. Kejriwal called Gadkari “corrupt” because not very long ago, the latter did come under the scanner for alleged massive illegalities in his business dealings, but managed to wriggle out since no legal investigation or prosecution were launched.

These two provisions are so broad in scope that every insinuation, unless proved to have been made in “good faith”, can land someone in prison. Someone like Kejriwal, who was incarcerated for six days until he was let out on bail yesterday. Now how does one prove “good faith”, that too, “beyond reasonable doubt”, since that remains the standard of proof in criminal law? Worse, a person can be taken into custody even while this seemingly Herculean task is getting done.

As if criminalisation of libel isn’t bad enough, punishing “slander” grants almost instant impunity if one is strategic enough. Take Kejriwal’s example, again. In October and November last year, he addressed a press conference and read out from a list of charges against business tycoon Mukesh Ambani. The businessman lost no time in slapping legal notices against every television channel which broadcast the conference. Libel chill, without a shred of doubt, for all the channels went silent. Whether Ambani’s fleece is as white as snow isn’t the question; his dark deeds of pulverising criticism are, and deserve the most trenchant critique.

It is encouraging to note that already demands are being made for decriminalising libel, but unless slander is banished from the statute books, dangers would continue to lurk. The Law Commission of India has taken a laudatory and timely step by releasing a consultation paper which seeks to unshackle the media from apprehensions of libel chill. But what happens to individuals — political activists, or whistleblowers? A possible solution lies in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. wherein the Supreme Court of the United States extended the Sullivan privilege (named after the legendary NYT v. Sullivan case) — that only statements made with naked malice or reckless disregard for the truth shall be held as defamatory — available to media houses, to certain categories of individuals also. Those “seeking governmental office” and those who “occupy positions of such persuasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes” were accorded protection. Recently, this has been adopted in international money laundering law of PEPs or Politically Exposed Persons. It includes, “individuals who are or have been entrusted domestically with prominent public functions, for example, heads of state or of government, senior politicians, senior government, judicial or military officials, senior executives of state-owned corporations, important political party officials”.

Back in 2011, the UNHRC (United Nations Human Rights Committee) issued a declaration condemning Philippines’ provisions of criminal libel as a violation of the ICCPR. One hopes India wouldn’t require such a slap on the wrists to amend the repugnant law which rewards dishonest claims of calumny.

This article was published on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org