By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

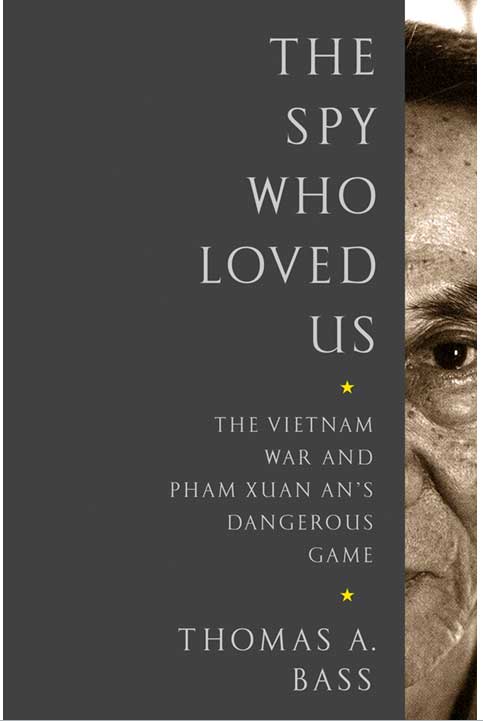

The kind of wariness one develops after many years spent trying to avoid people who want to kill you |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

It is a steamy night in June when I meet Bao Ninh at his house in Hanoi, where we will spend the evening chatting and sweating over green tea. Located in an old part of the city, the house has the usual barred gate opening into a covered patio filled with motorbikes. Behind the bikes lies a narrow room with yellowed walls lit by neon tubes. The room is furnished with a black couch, a couple of chairs, and a coffee table holding lychees, biscuits, and our bitter tea. I am accompanied to this meeting by my Vietnamese assistant and another young woman who is serving as our translator.

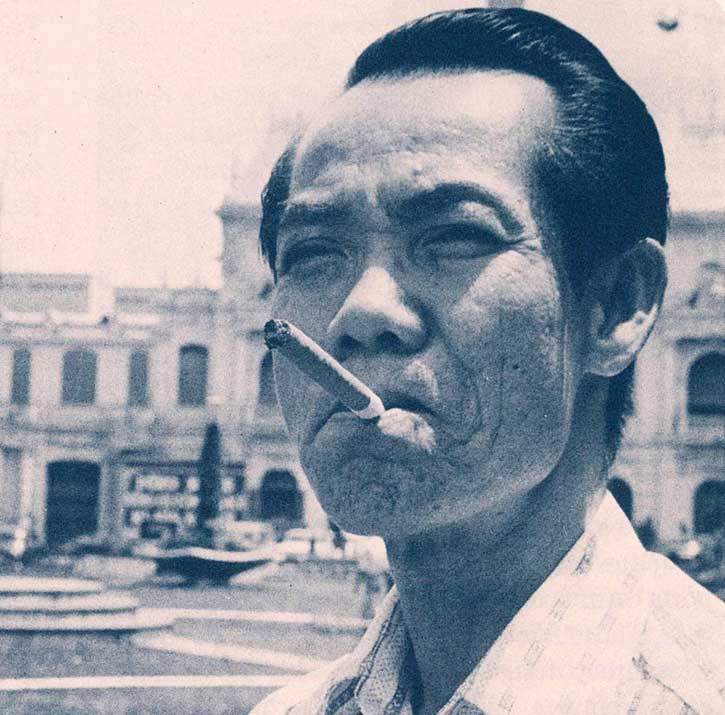

Ninh strikes me as hyper-cautious, with the kind of wariness one develops after many years spent trying to avoid people who want to kill you. Curled in a chair, ready to spring, his body looks as if it has muscles that have forgotten how to relax. When it enters my mind I can’t shake the idea that he has eyes in the back of his head. It is a large head, crowned with silver hair. Ninh’s eyebrows sweep over glancing black eyes, above sunken cheeks and a drooping mustache. Wearing a brown, short-sleeved shirt and black trousers, he chain smokes Camel Lights through smoke-stained fingers. A fan blows on us as we sit in the yellow gloom.

The next thing I notice about Ninh are his feet. He is barefoot, with wide, spatulate toes gripping the linoleum. Sunburned and flat, these are the feet of someone who spent years walking in rubber sandals, made out of old truck tires, down jungle paths with a backpack on his shoulders and an AK 47 in his hand. These are the feet of a peasant warrior whose physical needs have been stripped to a bare minimum. As he stares at me through his narrowed eyes, I realize that I am traveling heavy, with notebooks, digital recorders, and two assistants, while Ninh is still traveling light.

This first visit falls on National Journalists’ Day, which is celebrated mainly through bottoms-up drinking with one’s fellow cadre. Ever since his career as an author got derailed, after the denunciation campaign that began in the early 1990s, Ninh has supported himself writing a column for Literature newspaper (Bao Van Nghe), published by the Vietnamese Writers Union. “In principle, I have to go to work every day, but I am an old man, so I stay at home instead of going to the office,” says the author, who at the time was fifty-six. “I write an article a week. My last piece was on the countryside, about illiteracy among rural kids who are so poor that they have never been taught to read.”

After years of penning his inoffensive columns for Literature, Ninh was allowed to publish a short story collection in 2002 and another collection in 2005 called Daydreaming During a Traffic Jam. “As is usual in Vietnam, the publisher printed two or three thousand copies of Daydreaming and then allowed the book to go out of print,” he says. “You will have a hard time finding it now. I don’t even have a copy.” One story in the volume was translated and published in English as “Savage Winds.” “The title refers to the wind that blows in the Central Highlands,” he says. The rest of the stories remain untranslated. When I ask him if he minds his literary obscurity, Ninh shrugs. “I only care about the royalties,” he says.

In 2006, Ninh was also allowed to release a Vietnamese version of The Sorrow of War, for which he was paid a few thousand dollars. “The book has been translated and published in ten countries,” he says. “I don’t know anything about these translations. People tell me that sometimes parts of the text have been left out.” Again, he tells me how much he appreciates the royalties from these foreign publications.

“I have written two unpublished novels,” he says, when I broach the subject of censorship. “I do not intend to publish them.” The first, called “A Plain of Grass” (“Thao Nguyen”), is about a platoon of soldiers who capture a Montagnard village in the Vietnamese Highlands. Here they find a white missionary who has filed down his teeth like a Montagnard and gone native. What do the soldiers do with their half-white, half-Montagnard captive—kill him, set him free, or ship him to Hanoi? The question divides the unit, and they begin fighting among themselves. “The central character is a Catholic priest,” says Ninh. “The story is set during the war, when times were very different than they are now. We were ardent communists back then.”

“The second novel is about the interrelation of cultures and people, about the mixing of cultures. It, too, is about the war,” he says. The final, yet-to-be-named volume in Ninh’s trilogy is the most incendiary. It tells the story of South Vietnamese prisoners of war who have been sent to a POW camp in the north. (I have been told that the camp is located in Ho Chi Minh’s natal province of Nghe An.) Since most of the village men have died in the war, the local women mate with the southern soldiers and produce a new Vietnamese race, blended from Ho Chi Minh northerners and defeated southerners.

“The novel deals with soldiers, President Thieu’s soldiers,” says Ninh, referring to soldiers in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. “After the war they are arrested and sent to the north, to undergo a kind of brainwashing. Ten years later they are released.”

“My son has a girlfriend, who is the daughter of a Republican soldier,” he says, confirming that the new, blended Vietnam is already here. His son at the time is working in Hanoi for an American investment firm. “It is safe to have money now,” says Ninh. He mentions that his son appeared recently on TV, in a program about Vietnamese youth, and how he is helping to organize a film festival in Hanoi. “It’s strange to me how Vietnamese youth like American movies,” he says. “Americans and Vietnamese have something in common. We Vietnamese are often mistaken for Chinese, but we are very different. We are more open than the Chinese, more like Americans.”

Ninh returns to narrating the plot of his novel. “The soldiers are brought to the north.”

“To Nghe An province?” I ask.

Bao Ninh at his house in Hanoi (Photo: Thomas Bass) |

“I didn’t say that,” Ninh says, narrowing his eyes and retreating behind a cloud of cigarette smoke. Everyone knows that if he mentions Nghe An province, the book will be read as a commentary on Ho Chi Minh. He wants to drop the subject. “It is too difficult to understand,” he says. I urge him to continue.

“They are sent to a labor camp, in a residential area. Some northern women get pregnant. The soldiers are released and go to America. Then they return from America, to visit the women and their children.”

“So at this point the soldiers are viet kieu,” I suggest, using the term for exiled Vietnamese.

“You are right, but the Vietnamese people don’t like the term viet kieu,” he says. “This originated from the Chinese, and now you Americans use the term, but we prefer to say nguoi viet hai ngoai, overseas Vietnamese, which is more precise.”

“Do the soldiers stay in Vietnam?”

“Are they happy?” Bao Ninh replies. “It depends. Life in America is easier. They keep their American nationality. This is a fable about the history of Vietnam. It was written a couple of years ago. I do not intend to publish this now. For me, writing is more important than publishing. This is a story from the past.”

“Usually I never talk about my books, only with my closest friends,” he says. “I wrote the novel from my personal interests. I wrote about Vietnamese soldiers who worked with Americans. I tried to find out special things about Republican soldiers. I tried to understand them.”

“Did you succeed?”

“No one can understand another person fully,” he says. “I believe I understood them. It took me a long time, actually from the end of the war until now. I have traveled to the south a lot. I stayed in the south for several months after the end of the war. Many of my relatives live in the south. My younger sister, a teacher, lives there. It’s easier to earn money in Saigon than in Hanoi.”

As if to skirt away from a sensitive subject, Ninh says, “I haven’t finished writing the book yet. I spend most of my time drinking with friends.”

“Drinking what?” I ask.

He leans over and writes in my notebook “bia hoi,” draft beer, and then jokingly gestures toward my colleagues, “This is not a suitable subject for your translator,” he says.

“Middle-aged people like me are undisciplined,” he says. “I write at night, for three to four hours, starting after 10:00 p.m. I was born in the Year of the Cat, and cats don’t sleep at night. Writing is not an occupation here in Vietnam. It is a hobby. You don’t earn any money for it.”

My final question concerns Duong Thu Huong, one of whose books, Novel Without a Name, contains a number of passages resembling his own work. Ninh avoids the question. “There’s a lot of false information about her, saying she isn’t respectable, which isn’t true,” he says. “I have read all of her books, even those not allowed to be published in Vietnam because she is anti-communist.” To get my question answered, he suggests I go to Paris and ask Duong Thu Huong herself.

Part 11: The black cloud