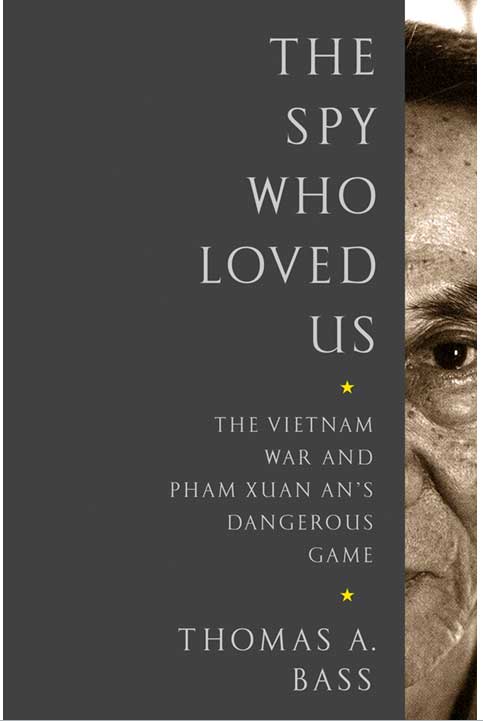

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

“Here in Vietnam censorship is inside the brain of everyone” |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

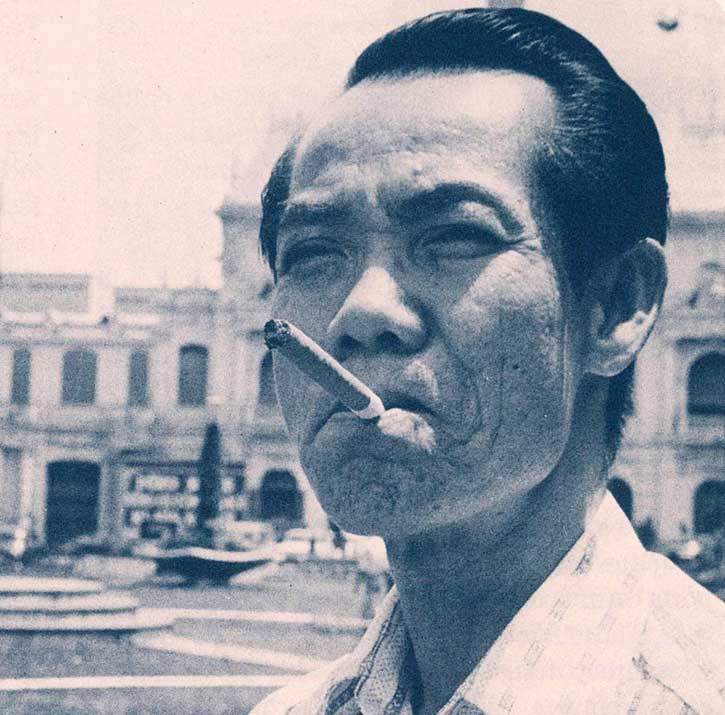

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

Nguyen The Vinh, editor at Hong Duc publishers, is the last censor I meet on my Vietnamese publishing tour. I am to appear at a Hanoi book fair for an author signing and then sit on a panel discussing my book. Flanking me are the sober Vinh, who, like many editors, seems to prefer books to authors, and another gentleman, Duong Trung Quoc, who also had a hand in getting my book published. Quoc is an historian and politician. I don’t know what kind of history he writes, but, as an elected member of Vietnam’s National Assembly, Quoc—a hearty fellow who resembles a Vietnamese Bill Clinton—is obviously a successful politician.

I try to hide my annoyance when most of the evening is devoted to discussing Pham Xuan An as a “perfect spy.” Remember, Vinh has edited—and censored—both the “official” biography of An and my own work. I have been advised to curb my tongue and not jeopardize the continued sale of my book. The ordeal continues over dinner, where I am still holding my tongue, while Vinh and Quoc tuck into a multi-course feast. In spite of their work doing the final pruning of my book, these men are the rainmakers who got it published. I owe them a couple of bucks in royalties, which I think I’ll donate to some of the millions of needy souls in Vietnam’s post-war diaspora. By the time our meal has moved from sautéed vegetables to steamed fish, my tongue has slipped enough to broach the subject of censorship.

“By law there is no censorship system in Vietnam,” says Vinh. “Mainly what we have is self-censorship.”

Quoc the politician agrees with his literary friend. “Here in Vietnam censorship is inside the brain of everyone,” he says. “It was your editors who cut your book, not the government.”

I ask them to elaborate on how a country without censorship manages to censor so many writers. “Publishers belong to the state,” says Vinh. “Everyone who works in the system understands this. For the higher purpose of the nation they have to sacrifice something. We have an expression here in Vietnam: ‘It is better to kill an innocent man than let a guilty one escape.’”

Quoc allows a smile to spread across his face, before gently chiding his friend. “You are speaking like a political commissar,” he says.

Later in the evening Quoc will hint at why my book was finally published after having been blocked for five years. “The authorized biographies on Pham Xuan An were works of stenography,” he says. “People printed what he told them to print. Your book is something different. It is documented and researched, but, more importantly, it captures his personality. This is why I thought it should be published.”

I take the compliment, but note that my book has not actually been published in Vietnam. A promotional teaser is for sale, while a complete Vietnamese translation can exist only outside the country. This will happen when the book is retranslated and released in Berlin as an electronic file stored on computers hardened against attacks from Vietnam’s censors. That Vietnam has censors trying to reach across the world and disable computers in Berlin makes these agents far less benign than Vinh would have me believe. In this case, the censors are working not as freelance gardeners, shaping topiaries in their minds, but as political operatives executing orders to attack people in foreign countries.

As we move from fish to grilled meats, Quoc indicates that he is going to give me an important scoop. Not only did Pham Xuan An continue working as a spy after the end of the Vietnam war, but he did so at the highest levels. “He was hieu truong, or dean, of the post-war military intelligence school in Ho Chi Minh City.” An’s eight-month stint in 1978 at the Nguyen Ai Quoc National Political Academy in Hanoi had prepared him for this important assignment.

I have seen no evidence supporting this claim, and, in fact, I suspect it is part of the propaganda campaign designed to make Pham Xuan An into a perfect apparatchik. The claim is even more improbable, because, earlier in the evening, Quoc had confessed that An, as a southerner who had worked for the Americans, was always distrusted by his northern colleagues. “People in Pham Xuan An’s position were not trusted by the government,” he says. “There were a lot of questions about him.” Apparently, these questions will remain unanswered for a long time. “It takes at least seventy years for documents in Vietnam to be declassified,” he says.

Later, to verify Quoc’s claim that Pham Xuan An was dean of Vietnam’s spy academy, I visit Bui Tin in his one-room garret in Paris. Tin is another famous journalist spy. He was deputy editor of Nhan Dan, Vietnam’s Communist Party newspaper, when he penned an editorial in the spring of 1990 praising the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the introduction of democratic reforms into the communist world. He was about to be cashiered by the Politburo, which was preparing to sign a secret agreement allying Vietnam and China. (“The Thanh Do agreement in September 1990 was the beginning of the Chinese colonization of Vietnam,” he says.) To avoid being arrested, Tin left his wife and two children in Hanoi and flew to Paris for a meeting of communist newspaper editors. After the meeting, he didn’t fly home. He thought the situation would reverse itself in a year or two. Vietnam’s progressive forces would regain the upper hand and reintroduce democratic reforms into the country. Twenty-five years later, Tin is still in Paris, while his wife, whom he has not seen since 1990, remains “under close surveillance” in Hanoi.

As an army colonel and confidante of General Giap, and as a fellow journalist who befriended Pham Xuan An after the two men met in 1975, Tin is a reliable source for double checking Quoc’s information. “Yes, Pham Xuan An wrote reports on his visitors,” Tin confirms, “and every once in a while he was asked to give lectures to the Ministry of Interior spies being trained in Saigon. But he was nothing as grand as the dean of a spy academy. The government treated him like an interesting artifact. He was a bauble they toyed with and admired. He was good for propaganda, but they never trusted him.”

In spite of his dubious pronouncements, I have warmed to Quoc as we plowed through a steady round of beers and ended the evening with toothpicks propped in our mouths, a sign of having eaten well. Quoc had surprised me with another confession. Unlike the old days, he said, the Vietnamese government is not run by intellectual giants and military geniuses. “Today the government of Vietnam isn’t smart enough to allow a Pham Xuan An to do what he did,” he says. “It requires bravery and intelligence to run a spy like that. What is your expression in English? ‘The first victim of war is truth.’ Here in Vietnam, we have the habits of war.”

By this point in the evening, convivial friends at the end of a good meal, agreeing on almost everything, my censors and I have begun toasting each other, bottoms up.

Part 9: Wandering souls