By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Historical facts are airbrushed out of the text and so, too, are various people |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

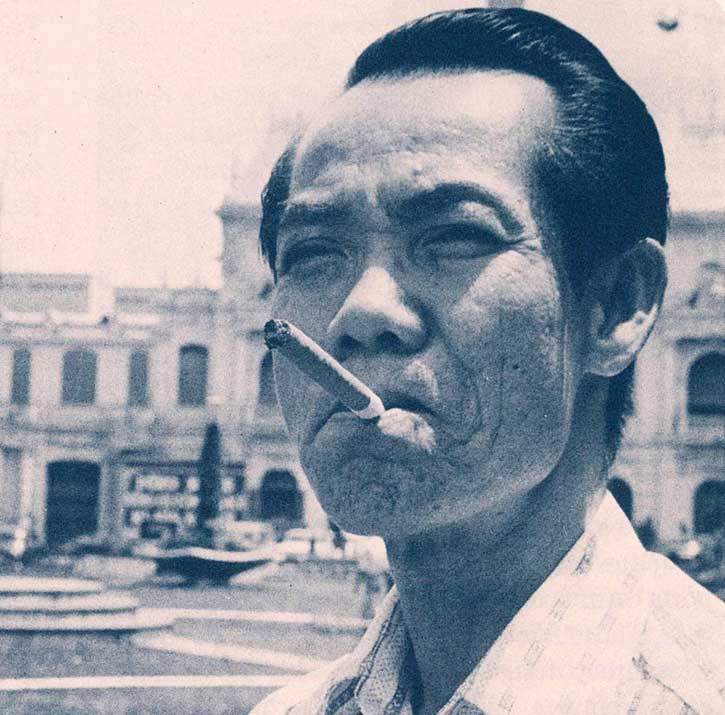

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

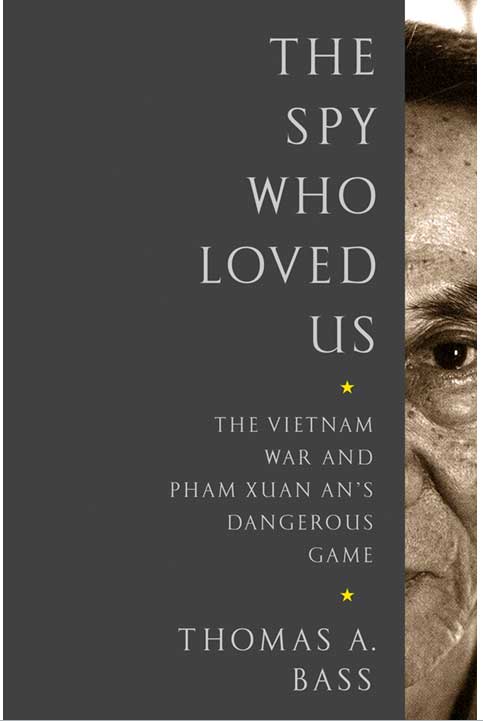

In June 2012, I receive an email from Thu Yen notifying me that The Spy Who Loved Us (or whatever the book is going to be called) has finally been approved for publication. Lao Dong (Labor) Publishing House, owned by Vietnam’s Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs, has stepped forward as our co-publisher. As a hex against other, less powerful censors, Lao Dong’s name will appear on the title page. The deal involves certain concessions, Yen admits. “After a very long time of applying for publishing permission, we finally got a positive result from Lao Dong (Labor) Publishing House,” she writes. “In order for your book to be published, there are cuts and changes that cannot be otherwise. However, the good points are that they edited rather well in terms of Vietnamese language in writing and literature.”

No page proofs are sent with her email. Yen offers instead a description of the censored text. “Given the highly sensitive content of your book, I do hope you can see these changes in the most supportive aspect, as necessary for your book to come to our readers.”

Attached to Yen’s email is a twelve-page document listing no fewer than three hundred and thirty three additional cuts to the book. Sentences, paragraphs, and entire pages have disappeared. The cuts begin with the title and carry through to the final acknowledgments. Historical facts are airbrushed out of the text and so, too, are various people. Vo Nguyen Giap, the great Vietnamese general who won the battle of Dien Bien Phu, is no longer a quotable source. Colonel Bui Tin, who accepted the surrender of the South Vietnamese government in 1975, has been scrubbed from the text and even from the acknowledgments. Scenes describing Pham Xuan An’s interaction with the Party, the military, the Chinese, and the police have all hit the cutting room floor. Forbidden also are any attempts at cracking a joke or being the least bit ironic.

“You can’t write the truth in Vietnam,” says one of my advisers, a former professor of literature who is now living in the United States. “My country is lost to lies. Your book had a human being at the center of it, but now it is stripped of all the details that made the story specific and compelling.

“The communists want the words to come out of your mouth,” she says. “Their official propaganda will look more authentic if it is authored by a Westerner. You are their tool. You can protest and negotiate what look to be small concessions, but in the end, they are going to win. They always win.

“Even the language in your book is now ugly,” she says. “It is opaque rather than clear. Many terms have been borrowed from the Chinese. Other words are what the French call langue de bois, bureaucratic jargon. The communists think they are superior when they use these words. They want to control everything, even your thoughts.”

“There is so much the censors don’t like, they just cut, cut, cut,” she says, after comparing the Lao Dong version of my book to Mr. Long’s manuscript. “I get a big headache just looking at this text.” Pham Xuan An is not allowed to “love” America or the time he spent studying journalism in California. He is only allowed to “understand” America. His quip that he never wanted to be a spy and considered it the “the work of hunting dogs,” is gone. His claim that he was born at a tragic time in Vietnamese history, with betrayal in the air, is cut. The Gold Campaign organized by Ho Chi Minh in 1946, when he solicited contributions for a bribe large enough to induce the Chinese army to retreat from northern Vietnam, is erased.

Pham Xuan An’s family is not allowed to have “migrated from north Vietnam to the south.” Nor is he allowed to have participated in the nam tien. This is the historic southward march of the Vietnamese, taking place over hundreds of years, as they worked their way down the Annamite Cordillera, occupying territory formerly held by Montagnards, Chams, Khmers, and other “minority” people. Praise for French literature is gone. He is not allowed to say that France created the map of modern Vietnam. His description of communism as a utopian ideal, unattainable in real life—cut. His praise of Edward Lansdale, as the great spy from whom he learned his tradecraft—cut. Throughout the text, North Vietnamese aggression is played down, South Vietnamese barbarism played up. The communists are always in the vanguard, the people always happily following. Pham Xuan An’s attempt to distinguish between fighting for Vietnamese independence and fighting for communism–cut.

We have only got to page thirty-eight, when my friend says, “They want to kill this book. They don’t like it at all.” Discussions of communist land campaigns and collective ownership—cut. The communists are no longer responsible for ambushing and killing Pham Xuan An’s former high school teacher in 1947. Instead, “there was an ambush” by unnamed agents. A description of John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert visiting Vietnam in 1951—cut. References to Vietnam’s offshore islands and oil fields, which are currently being fought over with the Chinese—cut. Claims that river pirate Bay Vien fought for the communists before switching sides—cut. “These people are getting more paranoid every day,” she says.

There is also a long list of errors in the translation, words that my Vietnamese editors have either misunderstood or refused to understand, words such as ghost writer, betrayal, bribery, treachery, terrorism, torture, front organizations, ethnic minorities, and reeducation camps. The French are not allowed to have taught the Vietnamese anything. Nor the Americans. Vietnam has never produced refugees. It only generates settlers. References to communism as a “failed god”—cut. Pham Xuan An’s description of himself as having an American brain grafted onto a Vietnamese body—cut. His analysis of how the communists replaced Ngo Dinh Diem’s police state with a police state of their own—cut.

The story of the first American casualty in the Vietnam war, OSS officer A. Peter Dewey, who was accidentally assassinated by the communists in 1945, is gone. Vietnamese army officers are written out of campaigns. The Tet Offensive is not allowed to be described as a military failure. Dogs are no longer barbecued alive. Sexual peccadilloes, mistresses, forced marriages—all disappear when communist officials are involved. Descriptions of Saigon in the weeks immediately following the end of the war, including food shortages and the tightening noose of state security—gone. Even the ban on cockfighting becomes unmentionable. That Boat People fled the country after 1975—cut. That Vietnam fought a war against Cambodia in 1978—cut. That Vietnam fought a war against China in 1979—cut. Pham Xuan An’s last wishes, that he be cremated and his ashes scattered in the Dong Nai River, have been cut. (Instead, he received a state funeral with the eulogy delivered by the head of military intelligence.) By the time we get to the end of the book, entire pages of notes and sources have disappeared. So, too, has the index, where so many words would have had to somersault into their opposites.

“Thank God we have come to the end,” says my friend. “This has given me white hairs and nightmares.”

The Lao Dong manuscript presents a conundrum. How does one respond to something as nefarious as this? My advisors suggested two solutions. Kill the project, or work out a hostage trade. Nha Nam and Lao Dong will be allowed to proceed with publishing the book, but only in exchange for giving me an unlocked version of the manuscript that can be restored to its original form and published on the web.

To prepare for these negotiations, I review the contract I signed with Nha Nam three years earlier. The publisher will make only “slight modifications in the original text of the work,” and these modifications “shall not materially change the meaning or otherwise materially alter the text.” I ask my agent in New York to send notice to our subagent in Bangkok alerting Nha Nam that they are in breach of contract for substituting a work of propaganda for a translation.

Along with paying me for translation rights—a delay occasioned by “accidental oversight”—Nha Nam begins backtracking on the “cuts and changes that cannot be otherwise.” They had wanted to call the book “Perfect Spy,” but now Yen agrees to restore an earlier title that Mr. Long and I had negotiated. “This translation being censored is what both parties have seen from the beginning,” she writes to my agent in July 2012. “The extent to which the translation has been censored may have shocked the author (as well as us). But we are in here, all the time now, and we know the situation in our country. We have gone to seven different state-owned publishing houses, and, in the end, only Labor Publishing would give us a license, with cuts and changes.”

My canceling the publishing contract would be “the most easy-way-out-solution,” Yen concludes, but “this would be unfair to us and our honest intentions. We would be very disappointed,” she says.

My hostage negotiations are not going well either. Yen demands the right to censor the book on the web, thereby extending Vietnamese hegemony throughout the universe. Eventually she retreats to demanding a six-month delay between publication of the book in Vietnam and its release on the web. We also agree that a disclaimer will be printed on the copyright page saying, “This is a partial translation of The Spy Who Loved Us. Parts of the text have been omitted or altered.”

By the end of the year, when I have yet to receive a copy of the galleys to review and our publishing license is about to expire, Yen writes, “Why have you agreed to work with Nha Nam if you don’t trust your Vietnamese editor? Are we less trustworthy than your friends?” I imagine her lacquered nails scratching the keyboard as she types. “We would like no more opinions from outsiders. It is not professional.”

In June 2013 Yen sends me a note announcing that Nha Nam is trying to secure another publishing license (the last one having expired), and she hopes soon to be writing with good news. She admits that editors in Vietnam are “scared” of the project. The following week I receive a request from Yen to “friend” me on Facebook.

Part 4: Not worth being killed for