By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

The web is where Vietnamese literature has moved, as the grey net of police surveillance, fines, exile and prison is cinched ever more tightly around the country’s journalists, bloggers, artists, musicians, writers and poets |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

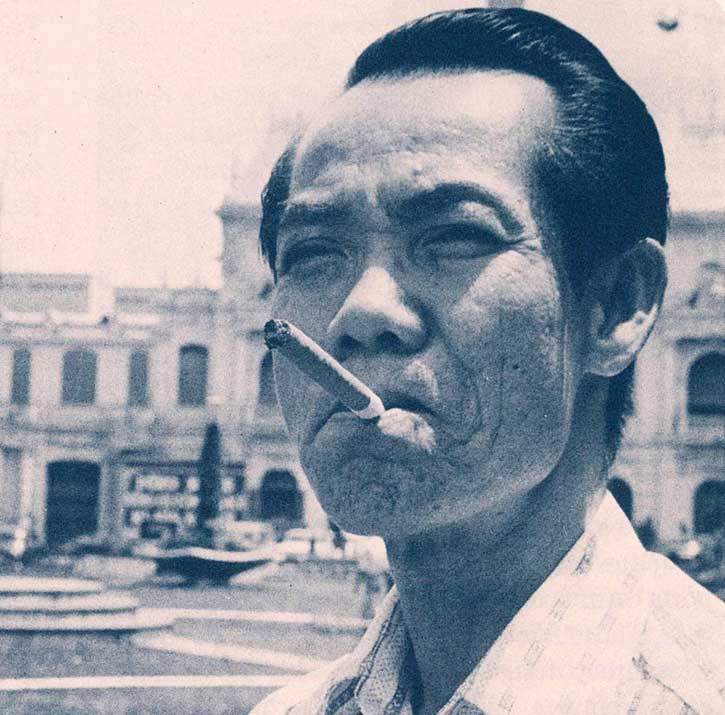

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

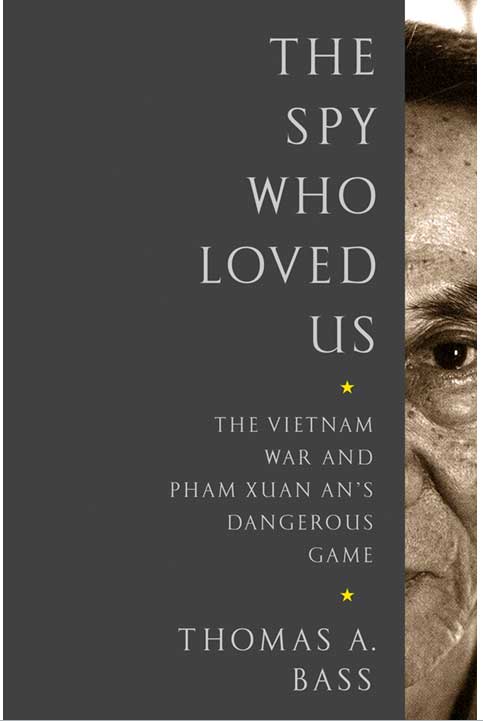

Sometime in March 2014—no one can tell me for sure, and, in fact, the book’s publishing license is not issued until May 2014—a Vietnamese translation of The Spy Who Loved Us appears in Hanoi. By this point, even the title of my book has been censored. It has been reduced to Z.21, a code name for Pham Xuan An, as if the book itself, like its hero, will try to travel unnoticed through the shifting terrain of Vietnam’s culture wars.

I had been sent a final list of censored passages and was settling down to review these cuts when I received the email telling me that the book had been published. This was a breach of contract, but I decide not to press the point, because I am now contractually free, in six months, to release my own uncensored version on the web. The web is where Vietnamese literature has moved, as the gray net of police surveillance, fines, exile, and prison is cinched ever more tightly around the country’s journalists, bloggers, artists, musicians, writers, and poets—yes, even Vietnam’s poets can get in trouble, as I soon learn on a visit to Vietnam.

I use the minor stir occasioned by my book’s publication (including a cover story in Communist Youth magazine) to schedule a trip to Southeast Asia. I want to meet the censors with whom I had been sparring for the past five years, or at least the ones who will step forward and talk to me. I arrive on the night flight from Paris to Hanoi at the end of May and begin swimming through a miasma of tropical heat and humidity, before taking refuge in the Church Hotel, near St. Joseph’s cathedral in Hanoi’s old quarter. From here I schedule a meeting with Nguyen Viet Long, my original editor at Nha Nam. I also schedule meetings with Nguyen Nhat Anh and Vu Hoang Giang, chairman and vice-chairman of the company. Later, I learn that two other people who played a role in this affair are willing to talk to me. They include Nguyen The Vinh, editor at Hong Duc, the state-owned publishing company that produced the final list of passages to be censored and then issued my publishing license. Also willing to meet me is Duong Trung Quoc, an historian and elected member of Vietnam’s National Assembly, who seems to have negotiated the political deals required to get my book—or at least a version of my book—published in Vietnam.

The translator of Z.21 is a Hanoi journalist named Do Tuan Kiet. Judging from his work (unfortunately, he is out of town during my visit), Kiet speaks Vietnam’s dominant northern dialect, which today is larded with Marxist-Leninist terms borrowed from the Chinese. This language grates on the ears of southern Vietnamese. It is not the language spoken by Pham Xuan An, the hero of my book, and, in fact, An mocked this speech. He dismissed the ten months he spent in 1978 at the Nguyen Ai Quoc National Political Academy outside Hanoi as “reeducation”—a failed attempt to teach him this jargon. “I had lived too long among the enemy,” he said. “They sent me to be recycled.”

After my book was translated, Long, my editor, began the serious work of censoring it. Over the years, as he tried to secure a publishing license, more and more changes were made to the text, as one state-owned company after another rejected the book. By the end, I imagine the project had grown ripe with the odor of danger. It was not something one wanted to touch if you valued your career as an editor at Police newspaper or the Ministry of the Interior. Long himself must have begun to look a bit suspicious. Then he left trade book publishing and went to work editing math texts for school children.

Long and I have agreed to meet at my hotel. He rings the bell and enters the room nervously. He sits on the edge of the sofa, apologizes for being late, and finally agrees to drink a beer. In his 50s, with dark hair framing his square head, Long is dressed in the uniform of a Vietnamese cadre: owlish eyeglasses, short-sleeved white shirt with pen in the front pocket, metal watch flopping around his wrist, gray slacks, and sandals. He glances around him, as if he is looking for listening devices, and begins answering my questions with the kind of guarded indirection one develops in a police state.

Trained as an engineer in the former Soviet Union, Long’s specialty was cybernetics or control systems for nuclear reactors, particularly the nuclear reactor in Dalat that the victorious North Vietnamese seized from the retreating Americans in 1975. A graduate of the Moscow Power Engineering Institute, Long taught himself English during his five years in Russia.

After chatting about his move from cybernetics to publishing, we begin talking about my book. “There was a serious battle to edit your book,” he says. “I was caught in the middle, being pressured by the author and my superiors. The regime has declared this a sensitive book. You can get in a lot of trouble for handling this kind of project improperly. That’s all I can tell you.”

“By law, there are no private publishing houses in Vietnam,” he says. “So Nha Nam has to ally itself with a state-run publisher every time it releases a book. We took your book to a lot of publishers, and they all turned it down. Finally, Hong Duc agreed to give it a publishing license. They’re a powerful publisher.”

“Why are they powerful?” I ask.

Long laughs nervously. “Let’s just say they’re powerful. That’s all I can tell you.” Later I learn that Hong Duc is run by Vietnam’s Ministry of Information and Communication, one of the country’s major censors.

“What about the material that was cut from the book?” I ask.

“The translator translated the entire book,” he says. “Then we removed the passages that had to be removed. We couldn’t leave them untouched. Publishing your book was a very hard process. A lot of subjects had to be censored, and there was no choice about removing them.”

When I ask for examples, he mentions Colonel Bui Tin, who defected to France in 1990 to protest Vietnam’s lack of democracy, and General Giap, who, before his death in 2013, wrote letters opposing China’s influence in Vietnam. “Nothing about these affairs can be written,” he says. “Everyone knows about them, but you can’t get a publishing permit if these things are in your book.”

“How do you know what has to be censored?”

“We must know. We observe. Maybe some people have different ideas, but we know what we’re supposed to do. A lot of it depends on timing,” he says. “We published a book by the Dalai Lama against China. Then, when the authorities noticed what we had done, we were forbidden from publishing more books by the Dalai Lama. In general, we couldn’t publish anything bad about China. For example, the 1979 border war between Vietnam and China was something we weren’t allowed to write about.”

Long has a nervous cough at the back of his throat. He declines a second beer. Again he glances around the room, finding nothing to make him look less glum.

“The censorship is often silent,” he says. “Without formally being banned, all the books that have been published can suddenly disappear from the shelves.”

“Publishing your book was a very hard process,” he says again. “It was the most difficult book for me.”

I ask Long if he is a member of the Communist Party. He is not a Party member, but his brother is. “There are political benefits from joining the party,” he says. “It helps you rise in state-run institutions.”

He declines another beer and says it’s time for him to retrieve his motorbike and ride home. He congratulates me on the publication of my book.

“It is not really my book,” I say, mentioning the four hundred passages that were cut.

“Four hundred is not so many,” he says. “We have an expression in Vietnamese, ‘If the head goes through, the tail will follow.’ In the next edition, maybe some of these passages will be restored.”

As Long slips out the door, he looks worried about having said too much during our brief encounter. I wish him well in his new job. “The pay is better,” he assures me.

Part 6: Vietnamology