By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

What the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

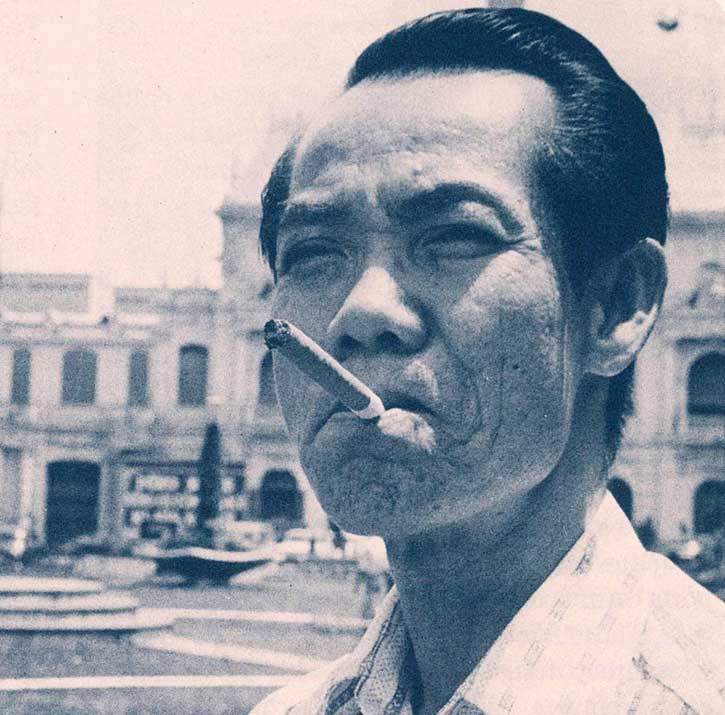

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

The process by which censorship works in Vietnam is described by Vietnamese reporter Pham Doan Trang in a blog post released in June 2013 by The Irrawaddy Magazine. Trang explains how, every week, the Central Propaganda Commission of the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hanoi and the Commission’s regional officials in Ho Chi Minh City and elsewhere throughout the country “convene ‘guidance meetings’ with the managing editors of the country’s important national newspapers.”

“Not incidentally, the editors are all party members. Officials of the Ministry of Information and Ministry of Public Security are also present. …At these meetings, someone from the Propaganda Commission rates each paper’s performance during the previous week—commending those who have toed the line, reprimanding and sometimes punishing those who have strayed.”

Instructions given at these meetings to the “comrade editors and publishers,” sometimes leak into the blogosphere (the online forums from which the Vietnamese increasingly get their news). Here one learns that independent candidates for political office, such as actress Hong An, are not be mentioned in the press and that dissident activist Cu Huy Ha Vu, who is charged with “propagandizing against the state,” should never be addressed as “Doctor Vu.” Also buried are reports on tourists drowning in Halong Bay, Vietnam’s decision to build nuclear power plants, and Chinese extraction of bauxite from a huge mining operation in the Annamite Range.

The weekly meetings are secret and further discussions throughout the week are conducted face-to-face or by telephone. “Because no tangible evidence remains that … the press was gagged on such and such a story, the officials of the Ministry of Information can reply with a straight face that Vietnam is being slandered by ‘hostile forces,’” Trang says. These denials were strained when a secret recording of one of these meetings was released by the BBC in 2012.

The Propaganda Department considers Vietnam’s media as the “voice of party organizations, State bodies, and social organizations.” This approach is codified in Vietnam’s Law on the Media, which requires reporters to “propagate the doctrine and policies of the Party, the laws of the State, and the national and world cultural, scientific and technical achievements” of Vietnam.

Trang concludes her report with a wry observation. “Vietnam does not figure among the deadlier countries to be a journalist,” she says. “The State doesn’t need to kill journalists to control the media, because by and large, Vietnam’s press card-carrying journalists are not allowed to do work that is worth being killed for.”

Another person knowledgeable about censorship in Vietnam is David Brown, a former U.S. foreign service officer who returned to Vietnam to work as a copy editor for the online English language edition of a Vietnamese newspaper. In an article published in Asia Times in February 2012, Brown describes how “The managing editor and publisher [of his paper] trooped off to a meeting with the Ministry of Information and the Party’s Central Propaganda and Education Committee every Tuesday where they and their peers from other papers were alerted to ‘sensitive issues.’”

Brown describes the “editorial no-go zones” that his paper was not allowed to write about. These taboo subjects include unflattering news about the Communist Party, government policy, military strategy, Chinese relations, minority rights, human rights, democracy, calls for political pluralism, allusions to revolutionary events in other Communist countries, distinctions between north and south Vietnamese, and stories about Vietnamese refugees. The one subject his paper is allowed to cover is crime, and the press is not toothless in Vietnam, Brown says. In fact, journalists can prove quite useful to the government by exposing low-level corruption and malfeasance. “To maintain their readerships, they aggressively pursue scandals, investigate ‘social evils’ and champion the downtrodden. Corruption of all kinds, at least at the local level, is also fair game.”

Another expert on censorship in Vietnam is former BBC correspondent Bill Hayton, who was expelled from Vietnam in 2007 and is still banned from the country. Writing in Forbes magazine in 2010, Hayton describes the limits to political activity in Vietnam, where Article 4 of the Constitution declares that “The Communist Party of Vietnam, the vanguard of the Vietnamese working class, the faithful representative of the rights and interests of the working class, the toiling people, and the whole nation, acting upon the Marxist-Leninist doctrine and Ho Chi Minh thought, is the force leading the State and society.” In other words, what the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses. “There is no legal, independent media in Vietnam,” says Hayton. “Every single publication belongs to part of the state or the Communist Party.”

Lest we think that Vietnamese culture is frozen in place, Trang, Brown, Hayton, and other observers remind us that the rules are constantly changing and being reinterpreted. “Vietnam … is one of the most dynamic and aspirational societies on the planet,” says Hayton. “This has been enabled by the strange balance between the Party’s control, and lack of control, which has manifested itself through the practice of ‘fence-breaking,’ or pha rao in Vietnamese.” So long as you “don’t confront the Party or pry too deeply into high-level corruption, editors and journalists can get along fine,” he says.

In certain circumstances, even journalists who pry more deeply can get along fine, depending on who is controlling the news leaks and for what end. This process of controlled leaks is described by another observer of censorship in Vietnam, Geoffrey Cain. In his master’s thesis, completed in 2012 at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, Cain writes that the Communist Party in Vietnam uses journalists and other writers as an “informal police force.” They help the central government keep regional officials in line, limit their bribe taking, and patrol aspects of public life that otherwise might remain in the shadows. This represents “soft authoritarianism,” which is characterized by “a series of elite actions and counter-actions marked by ‘uncertainty’ as an instrument of rule.” What is often described in Vietnam as a battle between “reformers” and “conservatives” is actually the method by which an increasingly market-oriented society can be “simultaneously repressive and responsive.” In this interpretation, journalists and bloggers lend themselves to the “informal policing” of free-market profiteers.

The “legal” mechanisms for the arrest of journalists and bloggers who overstep the boundaries, or accidentally get caught on the wrong side of shifting rules, include Article 88c of the Criminal Code, which forbids “making, storing, or circulating cultural products with contents against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” and Article 79 of the Criminal Code, which forbids “carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration.” Other grounds for arrest range from “tax evasion” to “stealing state secrets and selling them abroad to foreigners.” (This was the charge leveled against novelist Duong Thu Huong when she mailed one of her book manuscripts to a publisher in California.)

Other repressive measures lie in the Press Law of 1990 (amended in 1999), which begins by declaring, “The press in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam constitutes the voice of the Party, of the State and social organizations” (Article 1). “No one shall be allowed to abuse the freedom of the press and freedom of speech in the press to violate the interests of the State, of any collective group or individual citizen” (Article 2:3). Then there is the Law on Publishing of 2004, which prohibits “propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” the “spread of reactionary ideology,” and the “disclosure of secrets of the Party, State, military, defense, economics, or external relations.”

On goes the list of laws and regulations through various decrees and “circulars,” including Decree Number 56, on “Cultural and Information Activities,” which forbids “the denial of revolutionary achievements,” Decree Number 97, on “Management, Supply, and Use of Internet Services and Electronic Information on the Internet,” which forbids using the internet “to damage the reputations of individuals and organizations,” Circular Number 7, from the Ministry of Information, which “restricts blogs to covering personal content” and requires blogging platforms to file reports on users “every six months or upon request,” and the 2012 draft Decree on “Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Information on the Network,” which requires foreign-based companies that provide information in Vietnamese “to filter and eliminate any prohibited content.”

This 2012 draft Decree was codified the following year as Decree 72, which outlaws the distribution of “general information” on blogs, limiting them to “personal information” and making it illegal for individuals to use the internet for news reporting or commenting on political events. Condemning this statute as “nonsensical and extremely dangerous,” Reporters Without Borders, in an August 2013 press release, said that Decree 72 could be implemented only with “massive and constant government surveillance of the entire internet. …This decree’s barely veiled goal is to keep the Communist Party in power at all costs by turning news and information into a state monopoly.”

Vietnam has borrowed many of these techniques for monitoring the internet from China, its neighbor to the north. According to PEN International, China has imprisoned dozens of authors, including Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. Like China, Vietnam falls near the bottom in rankings of press freedom. Freedom House calls Vietnamese media “not free.” In 2014, Reporters Without Borders ranked Vietnam 174 out of 180 countries in press freedom. (It fell between Iran and China.) In 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists ranked Vietnam as the world’s fifth worst jailer of reporters, with at least eighteen journalists in prison. Recently, a draconian crackdown against bloggers and anti-Chinese protestors sent dozens more to jail, for terms as long as twelve years. Pro-democracy and human rights activists, writers, bloggers, investigative journalists, land reform protestors, and whistleblowers are all being swept up in Vietnam’s totalitarian dragnet.

Part 5: Literary control mechanisms