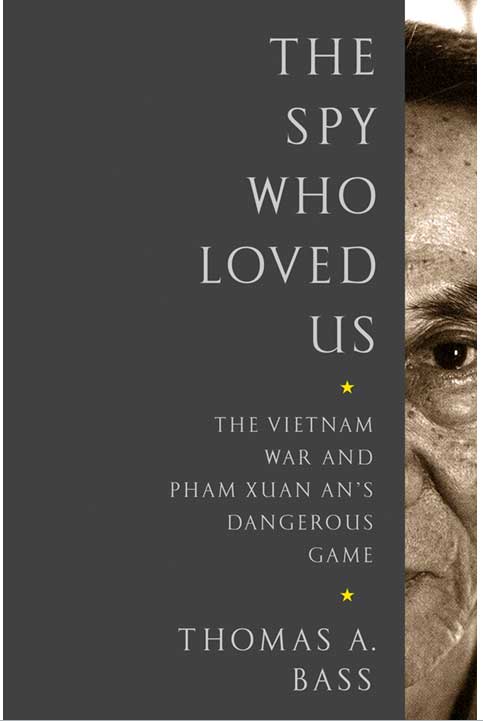

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Censors spend five years rewriting the story and struggle to get it as close as possible to the official version |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

To date, there have been six books written about Pham Xuan An, three in Vietnamese, one in French, and two in English. The self-described “official” biography, Perfect Spy, was published in the United States in 2007 and translated into Vietnamese a year later. “We turned the book red,” said someone knowledgeable about its publication in Vietnam. In other words, Vietnamese censors brightened the patriotic color in an already selective portrait of a national hero.

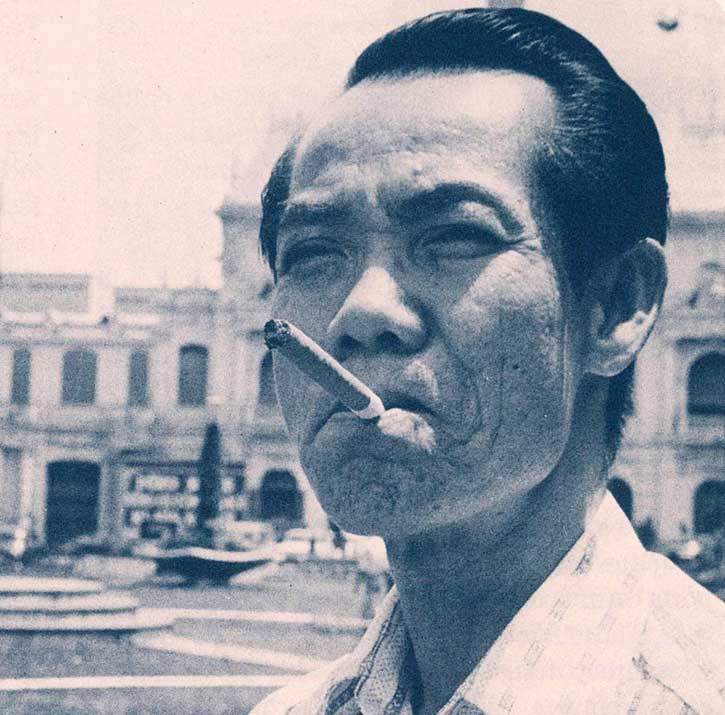

From the title alone, one understands that Perfect Spy portrays Pham Xuan An as a Vietnamese nationalist and patriot. The book also claims that he retired happily at the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. The problem with this narrative is that appears not to be true. Every spy has a cover, the life he hides behind while leading a double existence or, in Pham Xuan An’s case, a quadruple existence, since, at one time or another, he worked for the French Deuxième Bureau, the CIA, and both the South and North Vietnamese intelligence agencies. His spying for the French was limited to moonlighting as a censor at the Post Office, trimming Graham Greene’s dispatches to Paris Match. His work for the Americans included his being trained in psychological warfare in the1950s by Edward Lansdale and other CIA operatives.

His work for South Vietnamese intelligence, where he served as right-hand man to spy chief Tran Kim Tuyen, supposedly ended in 1962, when Tuyen was cashiered in a failed coup attempt. But An kept in touch with Tuyen, who remained an inveterate “coup cooker.” He took him food and medicine while the master spy was under house arrest (undoubtedly passing messages during these exchanges). Then An did Tuyen one final service. He saved his life. The famous 1975 photo of the last U.S. helicopter lifting off from the roof of 22 Gia Long Street shows a rickety ladder leading up to the chopper. The last man climbing that ladder, thanks to the intercession of his former right-hand man, is Tran Kim Tuyen. Why did An help the long-time head of South Vietnamese intelligence escape from the communists? “I knew I would be in trouble,” An told me. “This was the chief of intelligence, an important man to capture, but he was my friend. I owed him.” Who knows what bonds of loyalty were served or embarrassing questions avoided as Tuyen flew off to exile in England.

For twenty years An maintained his cover as a journalist, but when this was blown at the end of the Vietnam war, he developed a second cover—that of a happily-retired global strategist who spent his days shooting the breeze with Western journalists and other visitors. Recently I saw film footage of An being interviewed in 1988 by Vietnamese refugee and Hollywood actress Tiana Silliphant. Tiana was gathering material for her documentary From Hollywood to Hanoi. While being interviewed, An sits casually on the front steps of his house, with not one but two German shepherds guarding his back. Tiana asks him straight away about the people he betrayed and the friends who died as a result of his spying. An goes bug-eyed and shifty. One sees him making up his answers on the spot, beginning to spin the story that will develop into his second cover. “I retired from the military a few weeks ago,” he says. “I never betrayed anyone.”

An is on record saying that he retired from the military in 1988. But he is also on record saying that he retired in 2002 and again in 2005. This is when a visitor noticed a large, flat-panel TV in his living room, with a card attached saying that the TV was a retirement present from his “friends” in Tong Cuc II—Vietnamese military intelligence. It is more likely that An never retired, that he remained a member of the intelligence services until the day he died. Under his first cover, as a journalist, he worked as a spy from the 1950s until the end of the Vietnam war in 1975. Under his second cover, as a retired strategist, he worked as a spy for another thirty years—even longer than his first career. What he did as an intelligence agent in active service remains unknown, but he undoubtedly wrote reports on his visitors and offered the kind of political analysis for which he was famous. With his humorous quips about how the communists had failed to “reeducate” him, An deflected any suspicions that he was still working as a spy. This aspect of his life was only revealed after his death, when General Nguyen Chi Vinh, who was then head of Tong Cuc II, delivered the oration at An’s funeral. General Vinh’s speech about An’s “extraordinary military achievements,” accomplished while living “in the bowels of the enemy,” included the list of An’s military medals, each of which tells an important story about his life.

In a glancing reference, Perfect Spy mentions that Pham Xuan An won eleven military medals. He actually won sixteen military medals, and six of these medals were awarded after 1975. Fourteen of the total number of medals, and four of the medals awarded after 1975, are combat medals. These are given not for strategic analysis, but for specific military actions. An won medals for his tactical assistance in battles ranging from Ap Bac in 1963 and Ia Drang in 1965 to the Tet Offensive in 1968 and on to the Ho Chi Minh Campaign that ended the war in 1975. What An did to win four military medals after 1975 remains unknown.

To undercount An’s medals, ignore their significance, and overlook the fact that many of these medals were awarded after 1975 is part of the campaign to make Pham Xuan An a “perfect spy,” a benign figure, like Ho Chi Minh, removed from the staggering violence that marked Vietnam’s anti-colonial wars. In Perfect Spy other aspects of An’s career have been trimmed or suppressed. Softened in the narrative are his criticisms of communist incompetence and corruption, his acerbic comments about Russian influence in Vietnam, his attacks on Chinese meddling in the nation’s affairs, his jokes about having been “reeducated” in 1978, and his opposition to the Chinese-influenced clique that currently runs the country. Also downplayed or ignored are the details that explain why An’s wife and four children were sent to the United States in 1975 and then, a year later, recalled to Vietnam. In the version crafted for public consumption, and as reported by An’s “official” biographer, he remained in Saigon at the end of the war to care for his sick mother. In fact, the Vietnamese intelligence services planned to send An to the United States, where he would continue spying for the communists. Only when this plan was overruled by the Politburo was An forced to stay in Vietnam and recall his family. This information about An’s post-war activities reveals how Vietnam intended—and undoubtedly succeeded—in placing spies in the United States at the end of the war. It also reveals a rift between the country’s intelligence services and the Politburo, a rift that Vietnamese propaganda would like to paper over with a story about a sick mother.

Once the shadows are put back into Pham Xuan An’s life, the censors are bound to object to his less-than-perfect narrative. In fact, they will spend five years rewriting the story and struggling to get it as close as possible to the official version. Nha Nam’s gambit was flawed. Because one book about Pham Xuan by a westerner had been translated and published in Vietnam did not mean that a second book would follow easily. In fact, as we learned recently, even the “red” version of An’s life had been a hard sell. This was revealed in a State Department cable of September 2007, which was released by Wikileaks in 2011. The cable, by a consular official in Ho Chi Minh City, describes how the Vietnamese translation of Perfect Spy, although it was published by a government-owned company, was nearly pulped at the last minute by censors in the Ministry of Public Security. They objected “to the numerous quotes from Pham Xuan An lamenting that Vietnam had simply traded one overlord for another—the Soviet Union—and his criticism of post-war policies.” The editors were in trouble for “supporting the publication of a book in which one of the country’s most renowned heroes unleashes broadside attacks on post-war GVN policy and the closed nature of Vietnamese society.” According to the consular memo, “the pro-reform faction within the GVN” got “the upper hand” over “the counter-reform faction” only when the president of Vietnam himself gave his approval to publish the book.

One can see in these stories about Vietnamese censorship how the rule of law has been replaced by the rule of the jungle. Powerful people will do everything possible to protect their prerogatives. I am alarmed by these stories, but many people yawn when I talk to them about censorship in Vietnam. “What do you expect?” they say. “There’s nothing surprising here.” Even my Vietnamese friends have succumbed to fatalism and a strange belief that they can read around corners. “I can tell where a book has been cut,” novelist Bao Ninh assured me. “We know what’s missing. We just can’t talk about these things.”

It is hard to argue against censorship in the face of rampant cynicism, but a worthy effort was made recently by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen. In an essay written for Index on Censorship in 2013, Sen chastises his native India for thinking that they should emulate China, which appears to be the model for how authoritarian governments can swap personal freedom for economic growth. Sen argues the opposite position, that “press freedom is crucially important for development.” Free speech has “intrinsic value,” he says. It is “a necessary requirement of informed politics.” It gives “voice to the neglected and disadvantaged,” and it is crucial for “generating new ideas.” China appears to be doing quite nicely at the moment, but Sen—an economist who did his award-winning work on the theory of famine—reminds us what can happen when propaganda replace news.

“There is an inescapable fragility in any authoritarian system,” he writes. The last time this phenomenon revealed itself in China, during the botched agrarian reforms of the Great Leap Forward, the country suffered one of the world’s most devastating famines. “The Chinese famine of 1959-1962 … killed at least 30 million people, when the regime failed to understand what was going on and there was no public pressure against its policies, as would have arisen in a functioning democracy.”

“The policy mistakes continued throughout these three years of devastating famine,” says Sen. “The information blackout was so complete with censorship and control of the state media that government itself came to be deceived by its own propaganda and believed that the country had 100 million more metric tons of rice than it actually had. Eventually, Chairman Mao himself made a famous speech in 1962, lamenting the ‘lack of democracy,’” a lack that, in this case, had proved lethal. India and other parts of the world might be tempted to emulate China, in light of its double-digit growth, but people would be foolish, says Sen, to adopt the anti-democratic measures that weaken totalitarian systems and make them susceptible to believing their own lies.

Part 8: The habits of war