By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

The dance of the censors, with works allowed to appear in print and then removed from bookstore shelves and then reprinted in altered form, shadows all of Vietnam’s writers |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

It is a sunny morning in July 2012 when my daughter Maude and I set out to meet Duong Thu Huong, Vietnam’s best-known novelist, who is currently living in exile in the 13th arrondisement of Paris, the city’s Chinatown, southeast of the Seine. I know from talking to her on the telephone that Madame Thu Huong speaks heavily-accented French, rich in vocabulary, but weak in grammar. She says she learned French in prison, during seven months of solitary confinement in 1991. After falling out of favor as the “fille bien aimée par le Parti” (the darling of the Communist Party), she was arrested for “selling secret documents to foreigners,” the documents being, in this case, the manuscript for her fourth work of fiction, Novel Without a Name. Allowed to have one book with her in prison, Huong chose a French dictionary. Hence the rich vocabulary and wobbly grammar.

My daughter lives in Paris and speaks fluent French. She will help translate, but I have also brought her along as a witness in case the interview gets tricky. Huong lives alone in a two-room apartment on the ninth floor of a modern building with a car dealership on the ground floor. She works at night, writing from midnight to six in the morning, sleeps until noon, and then spends the rest of the day on “la lutte.” The French word for struggle usually entails a political platform on the left, but, in this case, la lutte describes Huong’s fight against the Vietnamese Communist Party. Huong refers to herself as a “sans papier,” an illegal immigrant. Her passport was stolen in Marseille a few years ago, and neither the Vietnamese nor French government has offered to replace it. During the “Sarkozy mandarinate,” as she dismissively refers to the right-wing government of Nicolas Sarkozy, she was afraid to leave her apartment, for fear of being picked up on the street and deported. For Huong, one of the benefits of voting Sarkozy out of office was the fact that the new government gave her a French carte d’identité, although she still has no passport.

Huong is a lively woman, with flashing black eyes and shoulder-length hair, dyed blue—the same color as her eye shadow, the pillows on her sofa, her blouse, and jeans. Her round face is smooth and even-featured, with tattooed eyebrows and rouged lips that break often into a winning smile. She has the hands of a musician, with long, tapered fingers that have begun to curl with arthritis, but her girlish charm and colored hair make her look younger than someone born in 1947. Seated in the salle de séjour that doubles as her office, she plies us with cherries, sliced pineapple, tea, and chocolate.

Huong is a natural-born story-teller. She answers my questions in discursive loops that reach back through hundreds of years of Vietnamese history. We begin by talking about her family, which sets the scene and dictates everything that follows in a Vietnamese narrative. A “beloved daughter of the Communist Party” might be expected to have working class roots, but Huong, born in a village north of Hanoi, is the granddaughter of a mandarin landowner. Her family lost its wealth and status by getting in trouble, first with the French, for manufacturing rice wine without paying the necessary fees to the colonial government, and then with the Communists, for being bourgeois landowners during the agrarian reforms of the1950s.

Her grandmother, Le Thi Cam, sold half the family land to bail out of prison an alcoholic uncle. (The hapless male saved by a noble female is a common trope in Huong’s fiction.). Huong’s father fought in the maquis against the French and led a troop of engineers in General Giap’s signal corps, but the General did nothing to save Huong’s father during Vietnam’s Maoist-inspired land campaign. In 1954, he was sent to a labor camp in the mountains. (This will become another trope in Huong’s fiction—Party ideologues protecting their own prerogatives, while throwing their loyal followers to the mob.)

After losing their land, Le Thi Cam and three of her four sons moved to south Vietnam. Huong’s father, the youngest, worked for the post office after he got out of prison. Her mother taught in a primary school. In spite of the ardor with which Huong joined her classmates in chanting “Down with the landowners!” she was penalized for her class background. Not allowed to learn foreign languages or go to university, she enrolled in art school and then dropped out in 1967, at the age of twenty, to join a Communist youth brigade. She played accordion in a troupe of female singers and dancers who were sent to the military front to raise morale. Out of her art school class of eighty, Huong tells us that two others survived the war, one with no arms and the other crazy from shell shock.

Huong spent seven years in the jungles and tunnels north of the 17th Parallel, the dividing line between the opposing armies and the most heavily bombed part of Vietnam. A girl crouching next to her was killed by a bomb that left Huong deaf in her right ear. Her fiancé was also killed. In 1968 Huong married a fellow student from the Ministry of Culture Arts College. She gave birth to a son, Minh, in 1970, and a daughter, Ha, in 1972. “He was not talented enough to perform at the front,” she says dismissively of her husband, whom she divorced in 1982. (Her unhappy marriage provided Huong with another theme that runs through her writing. Wars are fought by good men who die young. The Party hacks with special privileges survive, while the unlucky women who marry them will either suffer in silence or revolt against these men who oppress them.)

After the war Huong began writing screenplays for propaganda films and working as a “nègre,” a ghostwriter, for communist generals penning their memoirs. Five of her scripts were made into forgettable movies by the Hanoi Fiction Film Studio. She wrote anti-Chinese tracts while serving as a combatant-reporter during Vietnam’s war with China in 1979. She was admitted to the Communist Party in 1985 and traveled to the Soviet Union the following year in a delegation of screenwriters. She also began publishing fiction, beginning with a short work called Journey Into Childhood (1985). Her first full-length novel, Beyond Illusions (1987), tells the story of a woman’s disillusionment with her marriage, which parallels her falling out of love with the Communist Party. In bed—in government—unworthy men plague women everywhere. The novel sold as many as a hundred thousand copies before it was banned.

According to Nina McPherson, who for a decade worked as Huong’s English translator into English, the artist first tangled with Vietnam’s censors in 1982, when one of her screenplays was suppressed. Huong protested at a Writers Union congress, but banning orders against her work remained in place until 1985. Perhaps as a result of joining the Communist Party, Huong was allowed to publish her writing for the next two years, until her novel Paradise of the Blind, an attack on Vietnam’s Maoist land reform campaign, was banned in 1988. Paradise—the first Vietnamese novel published in the United States in English—tells the story of a young woman who labors as a “guest worker” at a textile factory in the Soviet Union. The book attacks Party hacks who use their political connections to traffic in consumer goods. It also attacks the government officials who implemented Ho Chi Minh’s disastrous agrarian campaign. Equally radical is Huong’s redefinition of the Vietnam war, which, by this time, she has come to see not as a holy crusade against Western invaders, but as an internecine struggle among north and south Vietnamese family members.

Huong publishes one more novel in Vietnam, The Lost Life (1989), before the censors began moving against her with increasing ferocity. She is expelled from the Party in 1990 and arrested in 1991. This ends her career as a novelist published in her own country. Her next three books, Novel Without a Name (1991), Memories of a Pure Spring (2000), and No Man’s Land (2002), will appear only in foreign editions. None of her books is legally sold today in Vietnam, with the exception of some stories that the government bowdlerized and republished in 1997. (This allows them to claim with a straight face that the author is not censored in Vietnam.) The dance of the censors, with works allowed to appear in print and then removed from bookstore shelves and then reprinted in altered form, shadows all of Vietnam’s writers, but none more than Duong Thu Huong. Beginning with Novel Without a Name, she has published her works in French, English, and overseas Vietnamese editions, but not in Vietnam. The sole exception is her eighth novel, The Zenith (2009), which Huong allowed to be released in a Vietnamese edition on the web. The book has been read online by a half million readers, says Huong of this novel about the murder of Ho Chi Minh’s wife in 1958 by the Vietnamese Communist Party, who wanted the “father” of the country to preserve his purity.

“My British agent tells me I shouldn’t release any more books on the web,” she says. Apparently, he was displeased by the lost sales. “My life is dedicated to the fight against communism,” she says. “Writing is in second place, and I leave everything having to do with that to my agent.” For someone who dismisses her writing, Huong is remarkably prolific. Her ninth novel, Sanctuary of the Heart, published in France in 2011, tells the story of a Vietnamese gigolo kept in a luxurious villa by a wealthy businesswoman. Her tenth novel, The Hills of Eucalyptus, published in 2014, is the story of a homosexual man imprisoned and sentenced to forced labor.

Today, Huong has an international and generally appreciative audience. In 1991, for example, she was awarded France’s Prix Femina. In the words of one critic, “She is unmatched in her ability to capture the small, telling details of everyday life.” Other readers are more critical. Reviewer Brendan Wolfe calls her style “intensely sentimental and unfashionably melodramatic.” Vietnamese American poet Linh Dinh, who appreciates “Huong’s literary gifts sans soapbox,” describes how her “fine descriptive passages are perverted by a heavy-handed political subtext. Its bias can be traced to the war, in which both North and South demonized each other.”

Huong would say that Linh Dinh and her other critics have missed the point. She cares more about politics than literature. Her life is dedicated to the struggle for social justice and democracy, a global campaign that employs novelists but values them foremost as propagandists. “We want to see a democratic government in Vietnam,” she says. “Our example is Korea. Here you have the same people, the same history, until the people are cut in half. In the north, under communism, the people live like wild animals in caves. In the south, you have a relatively powerful and prosperous country. This is how you liberate people, how you change society for the better. Our struggle in Vietnam is similar. It is very difficult, but one must not abandon hope.”

Phan Huy Duong, the exiled Vietnamese writer living in Paris who for a decade was Huong’s translator into French, says of the author that “she was the first writer who dared to criticize the Vietnamese land reform campaigns and the degradation of intellectual life in Vietnam under the communists.” The Maoist campaigns, lasting from 1951 to 1953, were followed in 1956 by the repression of intellectuals and artists—a dark period in Vietnamese history that ended, albeit briefly, only with the onset of the doi moi “Renovation” movement in 1986.

Unfortunately, doi moi, quickly gave way to the paranoia of today’s censorious regime. “Vietnamese literature is in a grave state,” says Duong. “The people in power have developed a mafia of corruption” that allows only for the publication of propaganda and third-rate authors imported from the West.

“It is the old resistance fighters like Bao Ninh and Duong Thu Huong who frighten the government, because they speak the language of the people,” he says. “These writers are the only ones who can bring Vietnamese literature and culture back to life.”

“Duong Thu Huong shows that the power of the communists resides solely in violence,” he concludes. “First, the popular violence against colonialism. Then the violence against the Vietnamese people themselves. … Duong Thu Huong is respected because she says out loud what everyone else in Vietnam only says to themselves.”

Apart from her novels and speeches at Party congresses, Huong’s most politically subversive act was a film, “The Sanctuary of Despair,” which she began shooting in 1986. Huong had discovered in the mountains near Tan Ky, at the narrow waist of Vietnam above the 17th parallel, a concentration camp holding seven hundred North Vietnamese soldiers. This “gulag-style psychiatric camp,” as Nina McPherson describes it, was filthy with excrement and disease-wracked prisoners who looked like walking cadavers.

Huong began filming in the camp. “It was a movie about soldiers driven crazy by the war,” she says. “They were thrown in a concentration camp in the forest to hide the fact that they had been driven crazy. They were treated like criminals. The authorities are hypocrites. They want to hide these facts. The soldiers were pissing and crapping everywhere. The place was filthy. The nurses and doctors had become crazy along with the soldiers. They, too, were prisoners.”

“This was the most atrocious, the most stupid war in our history,” she says. “This is why everything written about the war by the Vietnamese is nothing but propaganda, while the real history is hidden. All my friends were killed in the war. Others were driven insane. I am the only one who has returned to bear witness.”

“We are a people deprived of hope, “she says. “We yearn for freedom and are given only enough to survive. We are condemned to unhappiness. This destiny weighs on me. It crushes me. This is why I made this film. I would finish it and wait for the right moment to release it.”

Huong’s film was being processed at a lab in Saigon when government agents broke into the facility in 1988 and destroyed the negatives with acid. Officials moved to expel Huong from the Party, and, by the time she was arrested in 1991, Communist Party Secretary Nguyen Van Linh was referring to Huong as “con di cua dang,” “the Party’s whore,” a denigrating reference to everything she had done since working as a female performer at the front.

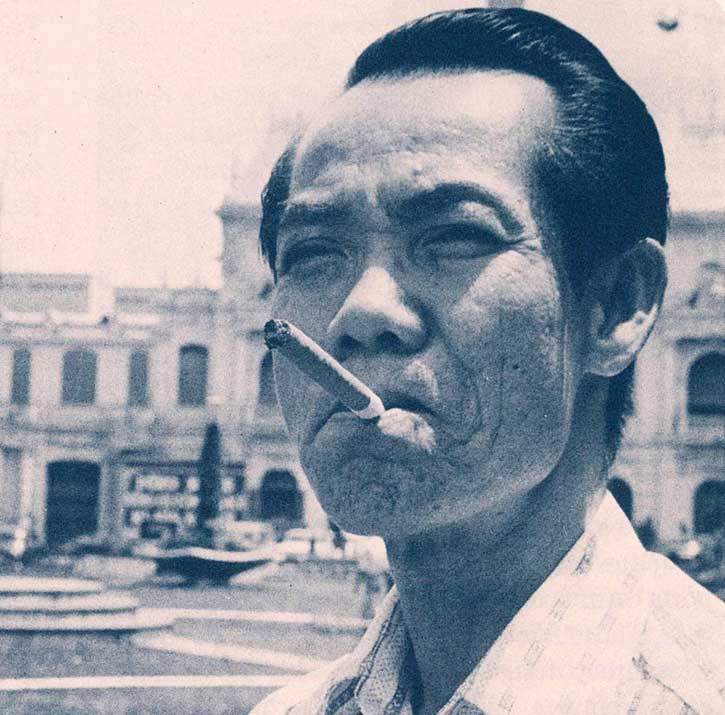

Duong Thu Huong (Photo: Thomas Bass) |

After spending seven months in solitary confinement in a high-security prison for political prisoners, Huong was released through the intercession of Danielle Mitterrand, wife of the former French president. “The French government also paid the Vietnamese a large bribe,” she says. Made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 1994, Huong was given political asylum in France in 2006. This is also the year she appeared on stage at the 92nd Street Y in New York. Praised by war novelist Robert Stone and cheered by the crowd, Huong, after introducing herself as a “criminal,” launched a fierce attack on governmental stupidity and corruption.

By the time I find her in Paris’s Chinatown in 2012, the French government has shifted from right to left, but her scorn for the French president (“that little mandarin Sarkozy”) is as piquant as that for the communist rulers back in Vietnam. “I was like a dish rag, a prisoner in my house,” she says of her life as “a sans papier” (an illegal immigrant) in France. Now that the French government has given her an identity card, “I’m as good as the street sweepers,” she says. “I have my working papers. I can circulate in France, but I can’t leave the country.”

Her feud with the French government is part of a larger feud that Huong has been waging with former friends and colleagues. “I detest Vietnamese men,” she says at the end of a story about why she has fallen out with her French translator, Pham Huy Duong. Huong has also fallen out with her American translator, Nina McPherson. Huong tells us that she is a member of no political party and not close to her fellow refugees or French hosts. Her friends, she says, are Americans or Australians, who, unlike the French, are not “too sophisticated.” “I am sorry for your daughter who has to work here,” she says.

Now that she has broken with her former translators and friends, Huong has nothing to do but write, producing a book every couple of years and becoming almost as quirky and famous as that other great Franco-Vietnamese writer, Marguerite Duras. Indistinguishable by now are the biographical details in Huong’s life and the recurring tropes in her novels. Women are ensnared through “the drug of love” by men unworthy of them. Sexual jealousy divides the world into possessed and possessors. Instead of socialist harmony we live in a fallen state of greed and hypocrisy. The solitary hero is the author speaking truth to power. To comfort herself in the loneliness of this struggle, Huong tells herself stories, late at night, when the ghosts of her dead friends return to talk to her. Expelled from her country, cut off from the translators who made her famous, disillusioned with the French political mandarins, a lonely woman with blue hair and tattooed eyebrows sits in front of me, a brave, even heroic figure who is creating out of her loneliness a partial and one-sided, but also a noble vision of what Vietnam could be.

We are headed into our third hour of conversation, when I broach the subject of plagiarism. Especially in their first twenty pages, Bao Ninh’s The Sorrow of War and Duong Thu Huong’s Novel Without a Name are remarkably similar. Both novels tell the story of a twenty-eight-year-old soldier fighting in the Central Highlands. One book opens in the Jungle of Screaming Souls, the other in the Gorge of Lost Souls. The infantryman hero encounters innocent girls mutilated by marauding troops, a dead orangutan with human characteristics, and narcotic flowers blooming in a hallucinatory forest. While Bao Ninh’s novel burns with the intensity of lived experience, Duong Thu Huong’s work often falls into set pieces with “soap box” dialogue.

Roneo copies of The Sorrow of War began circulating around Hanoi in 1989. A year later, what Nina McPherson calls the “hastily titled” Novel Without a Name, was sent to small overseas publishers in France and the United States. The best-selling author of three novels was rushing her fourth book into print, while a thirty-seven-year-old former soldier was trying to finish his thesis at the Nguyen Du Writers School.

“Scenes in your novel resemble scenes from Bao Ninh’s book,” I say. Before I can continue, Huong sits bolt upright on the sofa. Her face hardens. She adopts the formal French that inserts monsieur into its declarations. “Yes, this is true,” she says about the similarities between the two texts. “We were writing our books at the same time. Each of us was approaching the same subject from different directions.”

“But you wrote your book after the appearance of Bao Ninh’s novel,” I say, mentioning the date at the end of her manuscript, which says it was finished in “Hanoi, December 11, 1990.”

“I don’t know,” she says. “I only read his book many years later, here in France. I never read it in Vietnam. I am not close to Bao Ninh. We live in different worlds. I am a committed dissident, while he leads a normal life.”

Then Huong tells me a story about meeting Bao Ninh. The story is composed of Huong’s customary elements. It reveals a weak man overwhelmed by fear, but it has a surprise ending.

“When Bao Ninh visited me in Paris last year, I asked him, ‘Why is this book the only thing you have written in your life?’

“‘It is because of my wife,’ he said. ‘She was worried about the safety of our family.’ To protect his son and allow him to study in the United States, he rejected his other son. Literature is a child also. We give birth to it. He had to refuse this child out of fear for his family. It’s sad. This may be hard for you to understand, but he had to turn his back on his own book. The police tortured him by threatening his family.

“‘This was a mistake,’ he confessed. ‘It was wrong of me to do this. I regret it. I should have done things differently. You have to forgive me. I did it for my wife, so my son could finish his studies and travel overseas.”

“This is the inevitable bargain for every Vietnamese writer,” Huong says.

After talking for more than four hours, after drinking endless cups of tea and being plied with cherries and cashews, we are given as a parting gift not one but two boxes of chocolates. I am reminded of the fact that in Vietnam a gift is not a gift. It is an obligation.

“I believe you are a true journalist, a journalist who can interview gangsters and criminals,” she says on parting. “I myself feel like a sort of criminal who has just had her past history examined.”

“I’m sorry for making you feel like a criminal,” I say.

Back on the street, my daughter and I begin searching for a florist. I will be the next man in her life to send Duong Thu Huong his apologies, along with a large bouquet of flowers.

Part 13: Cyberspace country