By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Censors dictate even the smallest details |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

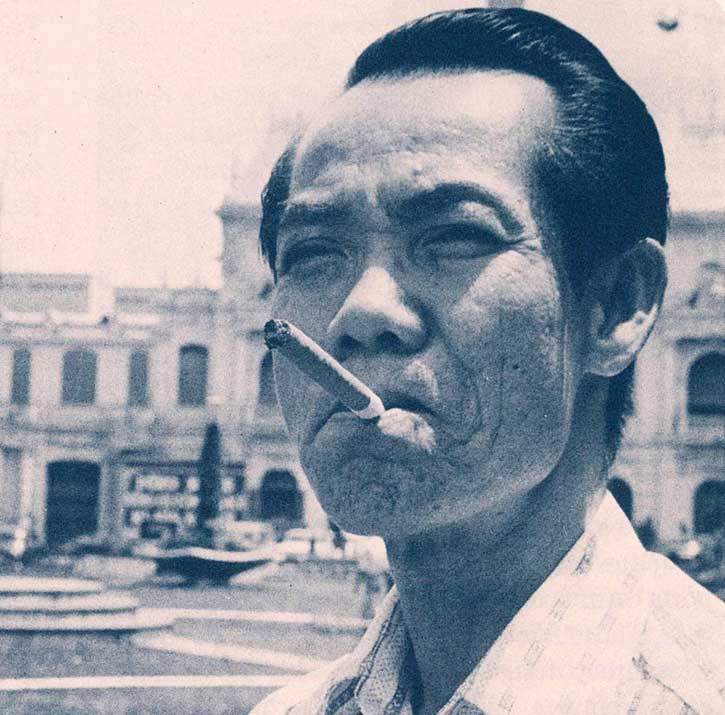

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

The next morning, taking a taxi to the Cau Giay district on the west side of town, I pass several of the lakes that dot downtown Hanoi to arrive at a tree-line boulevard where Nha Nam, my publisher, fills an old building with louvered windows that open onto iron-fronted balconies. Already by ten in the morning a gray blanket of heat and humidity has draped itself over the city. Nha Nam’s ground-floor bookshop is filled with translations of Proust, Kundera, and Nabokov, and I am pleased to find a stack of my own books displayed next to Lolita. I introduce myself to the receptionist and am led upstairs to meet Nguyen Nhat Anh, chairman of the company, and Vu Hoang Giang, his vice-director and partner. I had actually met Giang the night before. Without my knowing that he would be there, he had attended a lecture I gave at the Hanoi Cinematheque and introduced himself afterwards. As the chairman of Nha Nam presents me with a bouquet of purple lotus blossoms, I fear that my remarks the previous evening may have been too candid.

Nguyen Nhat Anh, a slender man in a black tee shirt, jeans, and sandals, looks more like a coffee shop habitué than the editor of a major publishing company. Known for his literary nose, he works at a desk covered with books and manuscripts piled ten deep. His partner, Giang, wearing an open-necked polo shirt, is a tall, handsome fellow with a ready smile and a small tattoo decorating his right wrist. I imagine they have divided the corporate turf between them, with Anh responsible for scholarship and Giang for sales. Later I learn that a lot of the manuscripts piled on Anh’s desk are actually publishing contracts, while Giang has his own literary interests, and, in fact, he was the person who finally arranged to got my book published.

Thu Yen, the editor with whom I have been sparring for the last few years, has not been invited to this meeting. She remains at her desk in the contracts department, while another translator has been hired for the occasion—a young Vietnamese woman, a former office manager at an American law firm. As the scholarly Anh and smiling Giang discuss the nuances of Vietnamese publishing, the young woman’s translations get shorter and shorter, until finally she seems on the verge of giving up completely. Fortunately, I have brought my own translator, and we will spend several hours later that afternoon reconstructing the conversation.

I take a seat on the couch in Anh’s office. Outside the louvered windows, the cicadas in the trees are making a fearsome racket. Giang has already warned me an in email about the “tight and rather heavy-handed censorship system of state-owned publishers in Vietnam. This you may not fully imagine.” I am offered a cup of green tea and then we launch into a discussion of censorship, how it is handled generally in Vietnam and particularly in my case.

Anh takes the lead, giving lengthy, formal answers to my questions, until Giang takes over when the boss heads to the espresso machine next to his desk and brews himself a cup of coffee. I am tempted to ask for one myself but decide to be polite and stick with tea. Anh describes how the censors dictate even the smallest details. He gives as an example the fact that political figures must have honorifics. One is not allowed to refer to the founder of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as Ho Chi Minh. He has to be Bac Ho—Uncle Ho—which inscribes him simultaneously into Vietnamese family structure and history.

“Censorship is a very tough question,” says Anh. “We don’t really have a system or set of rules for how it’s handled. All we know is that lots of publishers didn’t dare to publish your book.”

The jalousie doors and windows in Anh’s office open onto a porch overlooking the street, but they remain closed against the heat. Other than his desk, groaning under its layer of books, and a coffee table, piled with yet more books, the room holds nothing more than the couch on which I am sitting and bare green walls.

“Because another book had been published on the same subject, we thought this improved our chances,” he says. “We were sure we could get your book in print.”

I ask Anh why he chose a northerner to translate my book, someone who missed the nuances and even the jokes told by its southern hero.

“The differences are like music,” he says. “Singers sing the same songs but give them different interpretations. When we translated Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, we tried to keep it honest to the southern dialect. But in your case, we thought we were dealing with a political book, a work of non-fiction. The people who read these books are northerners, and you have to make the text understandable for them.”

I ask Anh and Giang to talk in more detail about censoring my book. They describe the by now well-known process, which begins with the translation, commissioned from someone who knows how the game is played. Then the book goes to the editor, who removes all the “sensitive” material.

“How does he know what to remove?”

Nha Nam Vice Director Vu Hoang Giang and Chairman Nguyen Nhat Anh (Photo: Thomas Bass)

“The process is dangerous, dangerous to the author, but also dangerous to the publisher,” says Anh. By this point in the conversation, he has kicked off his sandals and is cooling his bare feet on the tile floor. Overhead, a fan swirls tepid air around the room. Temperatures in Hanoi this spring are spiking over a hundred.

Anh tells me the story of a book of poems the company published in 2006 by an author named Tran Dan. Dan’s work has been banned in Vietnam since the 1950s, when he was involved in the nhan van giai pham affair. This was Vietnam’s version of Mao’s cultural revolution, a purging of writers, artists, and musicians who were blacklisted, imprisoned, and banned for fifty years. One of these artists was Van Cao, who, in 1945, had composed Vietnam’s national anthem. From 1957 until 1986, Vietnamese found themselves in the peculiar position of being allowed to play but not sing Van Cao’s anthem. Only when the words were changed was the song once again performed. Van Cao himself had long ago stopped composing, thereby joining the ranks of Vietnamese artists—hundreds of them, from the 1950s to the present—who have been driven into silence or exile.

With Mao long dead and his cultural revolution discredited, Nha Nam thought it was safe to bring the poet Tran Dan back into print. They had obtained a publishing license from a state-owned company in Danang and printed some of his poems when all hell broke loose. “The police came to the book fair and seized all our books,” says Anh. “Then they raided our offices and destroyed more books. This was terrifying for us. We thought we were going to be closed down and put out of business.”

“What went wrong?” I ask.

Anh lowers his voice and mentions the name of an agency named A25.

“Now it’s A87,” Giang says, correcting him.

Governmental departments that begin with the letter “A,” which stands for “an ninh,” meaning “security,” are legion, and A25—now known as A87—is the one that deals with publishers.

“In any case, it’s Cultural Security, cuc an ninh van hoa,” says Anh.

“What’s their address?” I ask.

“They don’t have an address,” he says, implying they are everywhere. The two men discuss among themselves in terse sentences what went wrong. None of their interchange is translated.

“There is no single organization in charge of censorship,” says Anh. “There are a lot of people involved.” Again, he mentions the Ministry of Public Security.

Giang mentions the Ministry of Information and Communication. “This is the office in charge of publishing,” he says.

Anh adds to this list the national police and other organizations. “It’s like a cloud,” he says. “They are everywhere.”

“Usually they don’t arrest editors,” he says. “This can happen to writers, but editors generally know in advance when they’re going to run into trouble.”

I ask them to speak in more detail about the censorship involved in publishing my book. This is when I hear for the first time about Nguyen The Vinh. Vinh is the man who produced the final list of cuts to my book and secured its publishing license. From their description of him, I get the idea that Vinh is a heavy-weight in the publishing world. The former director of various companies, he now works as an editor at Hong Duc, the state-owned publisher attached to the Ministry of Information and Communication. This company not only gave my book its publishing license, it also put its logo on the title page. Actually, the book has two logos on the title page: Nha Nam’s trudging water buffalo, with a book-reading buffalo boy (or girl) on its back, and Hong Duc’s white H inscribed inside a black D.

I learn another interesting fact about Vinh. He was the editor who secured the publishing license for Professor Berman’s Perfect Spy. The Vietnamese translation of this book was supposed to grease the skids for mine, and who better to perform this feat than the man who had already done it before.

As Anh busies himself making his cup of espresso, Giang takes over the narrative. “Your book was rejected by five or six publishers,” he says. “Other publishers who looked at it wanted to interfere a lot, changing the content. They kept asking to cut more and more. We resisted these changes, until finally Nguyen The Vinh agreed to publish it.”

“And what changes did he demand?” I ask.

Anh is pacing behind his desk. A frown darkens Giang’s face. “When you talk to him, you shouldn’t be too hard in your questions,” he says. “It could affect Vinh and the chances for your book to remain on sale.”

“Who asked Vinh to get involved?” I ask.

“Giang approached him,” says Anh. I can see that these men are nervous about talking to me in such detail. By now, both of them are sitting with their arms crossed over their chests.

“The publishers at Hong Duc wanted to write a forward to your book,” says Anh. “We rejected this idea.”

I can imagine how Hong Duc’s introduction would have reworked the standard tropes about Pham Xuan An as a “perfect” spy, an impeccable Communist cadre, who, nonetheless, garnered fulsome praise from his Western admirers. I am grateful to my editors for saving me this embarrassment.

“It was Vinh who took personal responsibility for publishing your book,” says Anh.

“You mean it can still be censored?”

Your book could be seized tomorrow,” he says. “No one knows where the trouble could come from. We have yet to see any negative signs, but someone can always find ‘sensitive’ items in a book.”

“What subjects would you like me to avoid talking about while I am in Vietnam?” I ask.

“Please remember that Vinh has his reputation and career on the line,” says Anh.

By now everyone knows my opinion of censorship—the cowardly business by which the powerful lie to the weak in order to protect their self-interest. I have no need to repeat myself.

“You shouldn’t be too direct with Vinh,” says Anh. “He was acting on directions from the publisher.”

“You should also know that your book is a living thing,” says Giang. “It can be published again, with material that was cut in the first edition added back in later editions.”

I assure Anh and Giang that I will do my best not to offend anyone. They know that an uncensored Vietnamese version of my book will be released later on the web.

“Right now we have no standards in Vietnam,” says Giang. “We don’t know our rights, and we don’t know from what direction the censorship is coming. But our system is changing. We hope you understand that we can improve. We can do better. We are learning how to function in the world of international publishing.”

“If your book is republished, we want to put back in the details that were cut,” he says. “You have a positive perception of Vietnam. People know this. So we’re asking for you to be patient. Give us some time to work things out. People appreciate you as an expert on Vietnam, a critic, sometimes a tough critic, but a fair one. Vietnamology—maybe that’s the right word for what you do.”

“How many ‘hard’ books do you publish each year?” I ask.

“In our career we are always working with difficult books,” says Anh. “This comes with the territory. But your book was a special case. It was the most difficult. I wanted to give up. I thought it was hopeless. I’m hot headed, and this was just too hard. I threw up my hands. ‘This book is never going to be published!’ I said. But my colleagues are more patient than I am. ‘Wait,’ they told me. ‘There is still a chance.’ It was thanks to Giang and Thu Yen that your book saw the light of day. They were patient. They persisted.”

“I felt like a hostage between two warring armies,” says Anh. “I was being fired on from two directions. The author was resisting cuts. The censors were demanding cuts. There are authors who know how this system works, Milan Kundera for example. He has lived under censorship. When we published his books, he understood our problems and agreed to let us do what we had to do. It would have been helpful if you had been more reassuring.”

“On behalf of the publisher, we want to tell you that we’re happy your book has been published,” says Giang. I suspect he’s feeling sorry about my having been compared unfavorably to Milan Kundera. Actually, I’m amused that a refugee from communist Czechoslovakia would prove tractable to being censored in communist Vietnam.

“This is not the first time that Vietnam and the United States have engaged in difficult negotiations,” I say. Anh and Giang appreciate the joke. “I’m glad we arrived at a happy conclusion.” We shake hands, and then I am asked to sit at Anh’s desk to sign copies of my book for members of Nha Nam’s staff. Apparently, everyone in the company wants a copy—perhaps before the book disappears from the shelves. All throughout lunch hour people keep drifting into Anh’s office with yet more copies for me to sign.

Part 7: Perfect spy?