Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Shafik Rehman (Photo: Reprieve)

Anisul Huq

Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs

Government of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Secretariat, Building No. 4 (7th Floor) Dhaka-100

4 August 2016

Dear Mr Huq,

We are writing to you as international press freedom, freedom of expression and media advocacy groups about the ongoing detention of Shafik Rehman, an elderly journalist in custody in Dhaka, to set out several serious concerns about his treatment.

We were pleased to note that on Sunday 17 July 2016 the Supreme Court granted Mr Rehman’s request for leave to appeal his detention.

Detention without charge

Mr Rehman was arrested on 16 April 2016 and denied bail by the High Court on 7 June 2016. After more than three months in detention, he has still not been charged with any crime.

He is being investigated by the Bangladesh Detective Branch, who entered his house without a warrant, inexplicably posing as a camera crew, on the day of his arrest.

The detectives missed a deadline on 16 June 2016 to submit a report to Metropolitan Magistrate SM Masud Zaman in Dhaka outlining the alleged case against Mr Rehman. The court extended the deadline until 26 July 2016, despite the fact that the First Information Report in this case was initially filed in August 2015 and the investigation period in the case has expired. On 26 July 2016, the police once again missed the deadline to submit their investigation report and a further deadline has now been set for 30 August 2016 – more than 100 days after his arrest.

Under international law, the Bangladesh authorities have a duty to promptly inform Mr Rehman of the nature of the case against him and either charge or release him. The delays in this case suggest that there is no evidence against Mr Rehman, and that he should be released.

Journalistic career

Mr Rehman is a professional journalist who has spent a lifetime working for freedom of expression. We are concerned that his arrest represents an attack on press freedoms and forms part of a worrying trend in Bangladesh. At the time of his arrest, Mr Rehman was editor of the popular monthly magazine Mouchake Dhil, with experience as a TV host and producer. Previously, he has worked for the BBC and edited Jai Jai Din, a mass- circulation Bengali daily.

The arrest of journalists like Mr Rehman raises concerns about the state of press freedoms in Bangladesh, where several prominent editors have been arrested in recent years.

Denied bail

Mr Rehman is an elderly man in poor health. He spent the first weeks of detention in solitary confinement, without a bed. His health deteriorated and he was rushed to hospital.

His family are seriously concerned about his health failing in prison, and he has missed important medical appointments while on remand.

There are therefore strong compassionate grounds for releasing Mr Rehman on bail, while any evidence (if there is any at all) can be gathered without jeopardising his health.

We hope that Mr Rehman’s appeal will be an opportunity for the Court to take stock of the serious concerns about the case against Mr Rehman and about his health and well-being while he remains in custody.

We appreciate you hearing our concerns and are grateful for swift action to guarantee Mr Rehman’s prompt release.

Yours sincerely,

Reprieve | Index on Censorship | International Federation of Journalists | Reporters Without Borders | Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech | Afghanistan Journalists Center | Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain | Bahrain Center for Human Rights | Canadian Journalists for Free Expression | Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility | Foro de Periodismo Argentino | Free Media Movement | Independent Journalism Center – Moldova | Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information | International Press Institute | Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance | Media Foundation for West Africa | National Union of Somali Journalists | Norwegian PEN | Pacific Freedom Forum | Pacific Islands News Association | Pakistan Press Foundation | Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA | PEN American Center | Public Association “Journalists” | Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Via post to:

High Commission for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

28 Queen’s Gate

London

SW7 5JA

Add your voice: Call on Bangladesh to free British journalist Shafik Rehman https://t.co/sslk4GsISX @Reprieve pic.twitter.com/CpXvOWpQ6U

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) August 10, 2016

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

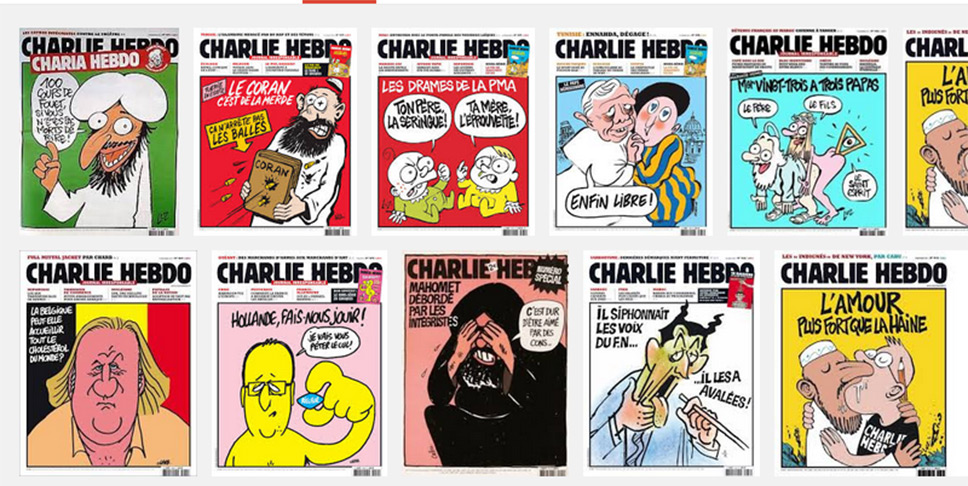

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

Credit: Saikat Paul / Shutterstock.com

So far this year, five secularists have been hacked to death with machetes by hardline Islamists in Bangladesh. Four writers — Avijit Roy, Washiqur Rahman Babur, Ananta Bijoy Das, and Niloy Chakrabarti — have been murdered, and on 31 October, Faisal Arefin Dipan, who published Roy’s books, was killed at his office in Dhaka. Two secular bloggers and another publisher were badly injured in a similar attack just hours earlier.

This spate of attacks began in earnest in 2013, when atheist writer Asif Mohiuddin was attacked with machetes. While he survived, blogger Ahmed Rajib Haider, attacked a month later, wasn’t so fortunate. At the time, the attacks were linked to political tensions over the ongoing war crimes tribunal. Today, the brutal assaults on secularists seem to have taken on a life of their own and the government has failed to take any decisive action, meaning secularists have been marked out as an easy target. “We don’t want to be seen as atheists,” said the prime minister’s son, Sajeeb Wazed, in May.

In 2013, militant Islamists issued a hit list of 84 bloggers. Numerous other lists are in circulation. For those who are under threat, the situation is terrifying: amongst the small community of “freethinkers”, as they describe themselves, there is a sense that no one is safe. One blogger, who wrote on feminism and religion who wished to remain anonymous, arrived in Europe on 30 October, the day before Dipan was murdered. “I had direct threats to my life; I stopped blogging but the threats continued and I couldn’t even leave the house. Even now, I can’t believe that I’m safe,” she told me over the phone.

The feeling is shared among many atheist bloggers, who use pseudonyms out of fear of reprisals. Prithu Sanyal (not his real name) was a mid-level government employee in Bangladesh who blogged for years on different online forums for atheist writers. He comes from a Muslim family, but later became an atheist and is openly critical of fundamentalism and religious intolerance. This year, he had a frightening experience. “Some unknown people, who introduced themselves as members of ‘Allah’s Army’, stopped me on the way of returning home from the office, and threatened to kill me with my wife and sons,” he told me via email. “They told me that now it is my turn to be killed and also threatened to kill my wife for being my accomplice, and my sons for being brought up without a religious view.”

Sanyal did not go to the police. He feared outing himself and losing his job. Moreover, he had no reason to believe that the government would offer him protection.

These fears are well grounded. Mohiuddin, the first blogger attacked with machetes in 2013, was soon afterwards arrested under blasphemy laws, illustrating the double threat of extremist violence and official repression. He remained in Dhaka for some time, but conditions were difficult. He covered his face with a mask when he left the house, fearing vigilante attack or arrest. He now lives in Germany and told me that he still regularly receives death threats. “It’s very normal for me.”

Sanyal has also left Bangladesh but his family remains in the country. He asked Index on Censorship not to mention his destination as he still has safety concerns. Bangladeshi fundamentalists recently published an international hit list, including citizens of America and Europe. The clear implication is that nowhere is safe.

One blogger, Nastiker Dharmakatha, wrote a widely circulated document in July explaining the dire situation faced by those who remain in Bangladesh despite being on the hit list. “Since the killing of Ananta Bijoy Das, most of us have been keeping ourselves caged in four walls,” he wrote. “Being the main earning members of our families, we have to go to office regularly. Some of us can’t even avoid evening or night duty at work.”

The letter goes on to explain that the damage inflicted on bloggers isn’t just physical but also mental. With bedroom murders not uncommon, “even staying home fails to guarantee our safety”. Police officers can enter a home at any time to arrest bloggers for “provocative writings”.

After the most recent attacks on publishers, there have been protests in Bangladesh at the continued killings and perceived impunity for the killers. The home minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal did nothing to allay the sense that the government is not taking action, telling reporters: “The law-order situation is good. These sorts of stray incidents occur in all countries.”

Such sentiments offer little comfort to those facing a continued and serious threats to their life.

This article was posted on 4 November 2015 at Index on Censorship

Secular bloggers in Bangladesh are fearing for their lives as four fellow bloggers were killed by machete-wielding extremists in the country earlier this year. Those murdered formed part of a hit list of 84 secularists and atheists targeted by Islamic fundamentalist groups for expressing their views online. The list was first circulated in 2013.

One of the bloggers, Bangladeshi-born US citizen Avijit Roy, set up the community blog Mukto-Mona. He was murdered with a machete in Dhaka in February. His wife was also wounded during the attack. Roy’s murder was followed by that of fellow secular bloggers Ananta Bijoy Das, Niloy Chatterjee and Washiqur Rahman. Threats to Chatterjee’s life were ignored by police.

Many writers in Bangladesh now fear they will suffer the same fate, with a number of them under 24-hour police protection. While five men, including one British citizen, have been arrested in connection with the murders, no charges have been made.

In response to the attacks, each member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board has been asked to produce a short video urging Bangladesh’s government to do more to protect bloggers’ rights to free speech and prevent further killings.

One board member from the US, Muira McCammon, who is currently studying for a masters in translation studies, explains how the Bangladeshi government’s reluctance to protect bloggers is leading people to question online safety. Her compatriot states that the views of atheists are just as important as those with religious beliefs.

South African human rights advocate Simeon Gready, along with two friends from Justice and Peace Netherlands, wants to raise awareness of bloggers under threat in Bangladesh.

The videos are compiled in the playlist below.