12 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the third of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform.

Despite the constitutional guarantees and international obligations, Belarusian laws, by-laws and practices of their implementation seriously restrict the media freedom. The Law “On Mass Media” and practices of its implementation have negative effects on media diversity, including complicated procedure of compulsory registration of media outlets. The law can be used to push independent newspapers to the verge of being closed down. The procedure of accreditation and laws on state secrets are also used to restrict access to information.

Law “On mass media”

The Law “On Mass Media” was adopted in 2008 and came into force on 8 February 2009, despite concerns voiced by the Belarusian Association of Journalists and the office of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. Five years after the law came into force, the fears of civil society and international organisations have proved to be well-founded. In particular, the following provisions of the law have been assessed to be restrictive:

• new media outlets have to apply for permission to be registered, which is an impediment to the right of freedom of expression;

• the process of licensing of broadcast media is non-transparent;

• the process of accreditation restricts journalists’ access to information;

• activities of a media outlet can be suspended or cancelled on the basis of a court appeal by the Ministry of Information, with no regard to proportionality or freedom of expression; the process to cancel a broadcasting license is even simpler;

• the government of the country receives the right to regulate activities of “media that are distributed via internet”, although there is no definition of online media in the law.

Registration of media outlets

The compulsorily registration of the print media, which has a chilling effect of media freedom, is still used in Belarus.

Article 13 of the media law provides for obligatory registration of any printed publication with a circulation of more than 299 copies. The registration process in Belarus has two stages; it is necessary to register an editorial board as a legal entity, and then to apply for registration of a media outlet. The law is arbitrary and presents a barrier to new entrants to the media market.

Editors of new media outlets must have higher education and at least five years of experience as editor-in-chief of a registered media. This is an arbitrary provision that makes it difficult for new media outlets to establish themselves. There are also additional restrictions that the Ministry of Information imposed in its decrees No. 17 and 18 of 7 October 2009, although they are not provided for in the law. There is a general rule that a company that is a unitary enterprise can be registered at its founder’s home address. Editorial boards of mass media that are unitary enterprises don’t have such right as the Ministry of Information demands them to have separate offices in non-residential premises.38

In 2010-2012 the ministry of information issued 105 refusals to register new media outlets. “These are not draconian measures. We have the media law; we have always acted and will continue to act within the framework of this law,” commented Aleh Praliaskouski, the Minister of Information.

Newspapers with a circulation of less than 300 copies are not obliged to register, but their activities are also regulated and controlled by the state. Each publication with a circulation of more than ten copies has to send at least five copies to state regulatory bodies according to “an obligatory mailing list.” Moreover, state bodies, first of all public prosecutors’ offices, demand such small-circulation publication to register as legal entities, thus obliging them to rent offices, pay taxes and employ editors according to the rules of the ministry of information. On several occasions the local prosecutors’ offices has issued warnings to publishers of such small-circulation media. These restrictions contradict the approach set out by the United Nations Human Rights Committee that stated that the requirements for the obligatory registration for small-circulation publications that are not issued on a regular basis is excessive; it has chilling effect of freedom of expression and it cannot be justified in a democratic society.

Suspension and closing down of media outlets

Possibility of suspension and closure of media outlets is still a major problem despite changes in the law. The previous media law provided for a possibility to close down a media outlet by a court decision if the media violated Article 5 of the law at least twice within a year. Article 5 of the media law contained a list of ten particular violations that could lead to a court appeal against a media outlet.

In the new Law “On Mass Media” this article is omitted, but this is not necessarily an improvement. On the contrary, Article 51 of the present media law allows for the closing down of any media outlet after any two (or, in some cases, even after one) warning, issued by the ministry of information or a prosecutor’s office, for any infringement, even a minor one.

In 2010-2012 the ministry of information issued 180 official warnings to mass media; two of them, Narodnaya Volia and Nasha Niva, were on the verge of being closed down. The ministry withdrew its claims, but the legal framework that allows closing media outlets down is still in place.

Case study: Appeals against Narodnaya Volia and Nasha Niva

In 2011 the ministry of information appealed to the supreme economic court with a legal claim to close down two leading independent newspapers Narodnaya Volia and Nasha Niva.

Prior to the appeal the ministry issued three warnings to Nasha Niva. Two of them were issued for articles over the reaction of the Belarusian authorities to a Russian documentary called “God Batska” (a reference to the title of Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather movie and a Belarusian word “batska” meaning “father”), in which president Lukashenko was criticised. The film was broadcast by the Russian NTV television channel in 2010-2011 to considerable public interest. One more warning was issued for an article about a bomb blast in the Minsk underground on 11 April 2011; according to the minister Aleh Praliaskouski, the reason for the warning was “improper coverage of the bombing.”

Narodnaya Volia received four official warnings before the appeal. The last one was issued for an article called “Goebbels-TV is on air” and was a critique of a highly sensationalist documentary broadcast by state television about events after the presidential election of 19 December 2010 in Minsk that accused the opposition of organising mass riots.

The newspapers appealed against the warnings and a court examination of their cases was postponed. While it was on hold, on 6 July 2011 the ministry of information issued one more warning to each of the two newspapers stating that Nasha Niva did not publish its subscription index in a single issue and that Narodnaya Volia had printed the wrong number of issues.

In July 2011 the Ministry of Information withdrew its court appeals to close the newspapers down. The decision to withdraw the appeal was arguably due to the significant public response to the case, including reactions from the international community. It is worth mentioning, that Narodnaya Volia and Nasha Niva were the two independent newspapers that were returned to the state press distribution systems in 2008; at that time it had been presented as a step forward by the authorities of Belarus in order to normalise their relations with the EU.

Despite the court appeals against the newspapers being withdrawn, each of the publication was fined 14 m roubles (about £1,800) for violation of Article 22.9 of the administrative code (“violation of the media legislation by a mass media outlet iteratively within a year after a previous written warning”).

Regulation of online media

While online media in Belarus are able to operate relatively freely, the authorities of the country reiterate their commitment to introduce tougher regulation for information websites to duplicate restrictions media face offline. It already resulted in restricting the access to several independent news websites that are included in an official black list.

Articles 11 and 17 of the media law provide for the registration of “mass media that are distributed via the internet global computer network” while giving space for the council of ministers to develop particular regulations. At the same time, the law provides no definition of online media. No governmental decree on the regulation of online media has ever been actually published, despite the law being in force for five years.

The current definition in the law allows the government to in theory consider many different types of websites as “mass media that are distributed via the internet global computer network”; including corporate websites that publish updates and personal blogs. Presidential decree No. 60 (On the Measures to Improve the Use of the National Segment of the Internet Network), signed on 1 February 2010, marked a new set of challenges to online free speech.

About 20 different by-laws and governmental decrees have been adopted since to regulate the implementation of different provisions of the decree No. 60. None of them specifically addresses online media outlets, but they influence activities of Belarusian websites. In particular, the present legislation provides for the following regulations:

• all Belarusian websites that provide services to citizens of Belarus must be moved to the national .by domain zone and be physically hosted on servers, located in the country;

• customers of internet cafes are obliged to register and present their passports before they can go online;

• internet service providers must identify all internet connections and store data about their customers and websites they visit; ISPs are also obliged to install technical system for search and surveillance in the internet, System for Operative Investigative Activities (SORM), that the police and security services officers have access to;

• “lists of limited access” of websites are introduced; the sites on the list are banned from access from computers at state bodies, educational institutions, public libraries, etc.

Governmental regulation of online media may be introduced in the near future. According to Belarus’s deputy information minister Dzmitry Shedko, “the most influential Belarusian websites may be given the mass media status.” The Deputy Minister stated in November 2013 a working group had been set up to address this issue. The ministry is taking a restrictive approach to regulation of online media. Only representatives of government agencies have been included in the working group. The deputy minister has argued the regulations are a necessity to make “the most popular and influential websites accountable for distributing any kind of information”, including a possibility of revocation of registration for breaking the regulations.

As Sedko reiterated in his letter to Index in November 2013, “at the moment the ministry of information is considering the issue in detail in order to elaborate an optimal decision to be suggested to the council of ministers.”

Independent media experts have noted that the proposals will not create additional opportunities for the journalists of online publications. In line with the practice of the current law, the regulation seems to be intended to introduce additional responsibilities for online media outlets to restrict their coverage in a similar manner to that of the printed press.

Possible media law reforms

The authorities of the country have been quite reluctant to discuss or implement recommendations on reforms of media-related legislation. Nor have there been changes to the implementation of the law to bring the practices of public bodies in line with international standards. In particular, the country’s officials have stated they do not recognise the mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti, and will not cooperate with him.

Dunja Mijatović, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, was able to make an official visit to Minsk in June 2013 and welcomed “the readiness of the authorities to intensify dialogue and co-operation with her office on much needed improvement of the media freedom situation.”

Still, the analysis presented in this policy paper shows the overall developments in the media field are no more positive than a few years ago. The authorities of Belarus show little sign of wishing to discuss reforms of the media field with civil society. Attempts by the Belarusian Association of Journalists to apply to the standing commission on human rights, national relations and mass media of the house of representatives of the national assembly to hold an open and public discussion on media-related laws and their implementation in Belarus were rejected. As was BAJ’s proposal to the national parliament to discuss reform of the media law with international experts, in particular the OSCE.

Andrei Naumovich, the chair of the standing commission, replied to BAJ on 15 February 2013, that all the suggestions were “considered in detail with the ministry of information.” According to the ministry, “at present the Law ‘On Mass Media’ functions stably, it allows solving current practical problems in activities of mass media, and fosters the advancing development of information field of the country.” Naumovich informed BAJ the parliamentary commission “considers initiating of amendments to the media laws to be unreasonable.”

Index on Censorship approached the ministry of information of Belarus in October and November 2013 to discuss media reform. The ministry did not reply to a request for a meeting in Minsk. The ministry responded in a letter with Shedko, deputy minister, stating that the ministry “conducts systematic analysis and monitoring” of implementation of media-related legislation in the country; it also “considers suggestions of citizens and legal entities on these issues” and “initiates amendments in the media law, when necessary” though gave no specific examples of this. In January 2014 Usevalad Yancheuski, the head of the principle ideological department of the presidential administration, informed BAJ that the ministry of information “is requested to invite representatives of journalistic organisations” to be involved in the work on possible amendements to the media law, but it has led to no particular steps so far.

Accreditation and state secrets laws as means of restriction of access to information

There are various ways in which access to information for journalists is restricted in Belarus. The main two of them are the accreditation of journalists and the use of secrecy laws.

The procedure of accreditation is understood by state bodies as a permission they are entitled to grant – or to reject – to a journalist for receiving official information from them.

Additional barriers to access to information are created by the laws on state secrets and state service. These laws contain vague and broad definitions of data that can be declared a state secret. More than 60 different state bodies and institutions have the right to attribute certain information to be a state secret; the list of organisations includes the ministry of information, the ministry of culture, the ministry of education, the National State Television and Radio Company and regional authorities. Loosely-defined provisions in these laws allow for the restriction of access to information of public interest by labelling certain data as a “state secret”.

Criminal defamation

Criminal defamation is chilling to freedom of expression. A prison sentence may lose a journalist their job, while a criminal record may make them unemployable in the future. Belarus continues to criminalise defamation, even though the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression has called for its decriminalisation.

Six articles of the Criminal Code provide for criminal liability for libel and defamation, while offering additional protection to state officials, including the president of the country. These articles have been used against journalists. In July 2011 the journalist Andrzej Poczobut received a three-year suspended jail sentence for libelling the president. A year later he faced similar charges again. The journalist spent ten days in detention in June 2012. In 2013 the new criminal case against him was cancelled and all charges were dismissed.

A criminal case against the journalist Mikalay Petrushenka was initiated in 2012. He was charged with insult of a state official; his article for Nash-dom.info website allegedly contained “public insult” of a deputy head of Orsha local authority. Linguistic experts who analysed the text found no insulting words or expressions there; the case was dropped in October 2012.

Belarusian law provides not only for criminal, but also administrative and civil liability for defamation. It can be noted as a positive development that in recent years there have been no administrative or civil libel cases against media or journalists were initiated by Belarusian officials.

Anti-extremism laws used to put pressure on media and journalists

Anti-extremist legislation has been used in Belarus to curtail media freedom. The current law “On Counteraction to Extremism” came into force in 2007. It contains vague and ambiguous definitions of terms “extremism” and “extremist materials” that allow for its arbitrary implementation.

On 10 January 2011 the ministry of information cancelled the broadcasting license of Avtoradio for distribution of information that the ministry considered “public appeals for extremist activity” after the authorities broadcast an election appeal by opposition candidate Andrei Sannikov during the 2010 presidential elections. The appeal contained the phrase “the fate of the country is determined not in a kitchen, but on the square” a phrase the authorities deemed as an appeal to extremism. All attempts of Avtoradio to appeal against the decision were unsuccessful.

In October 2012 the authorities started a full-scale tax inspection of ARCHE magazine. The department of financial investigations blocked bank accounts of the magazine, thus making its further issuing impossible. In two pieces shown by state television Valery Bulhakau, the editor of ARCHE, was in fact accused of “dissemination of extremist literature”. That slander campaign forced Bulhakau to temporarily leave the country. Later the case was dropped.

Forty-one copies of Belarus Press Photo album were confiscated on 12 November 2012 by Belarusian customs officers on the border between Belarus and Lithuania. The KGB, state security committee, appealed to court with a request to consider the album to be “extremist material”. According to the KGB, the photos “reflect only negative aspects of life of the Belarusian people with authors’ personal insinuations” and thus they “humiliate citizens of Belarus” and “belittle the authority of the state power.” The publication that contained the best press photos by Belarusian photo reporters was considered extremist by Ashmiany District court on 18 April 2013; all the confiscated copies of the album were destroyed. In September 2013 the ministry of information cancelled the publishing license of Lohvinau Publishing House which was the publisher of Belarus Press Photo album. The publisher appealed against the decision, but in November 2013 the supreme economic court of Belarus upheld the decision by the mnistry of information to cancel the licence of the Lohvinau Publishing House.

Other laws are also used to persecute journalists for their legitimate professional activities. In August 2012 Anton Suriapin, a journalism student, was charged with assisting an illegal crossing of the Belarusian border. He had posted photos on his blog of teddy bears dropped by parachute over Belarus by a Swedish PR firm to protest over the lack of media freedom in the country. He was arrested and detained by the KGB for more than a month, but later released. On 29 June 2013 the KGB announced that a criminal case against Anton Suriapin was dropped, and he was cleared of all charges.

Recent years have seen no improvements of the media-related legislation in Belarus, despite continuous calls for reforms from civil society of the country and international community. The media law remains restrictive; it fails to foster the development of pluralistic and independent news media through a complicated procedure of compulsory registration of new media outlets and possibilities for the state to close down existing media even for minor infringements. The authorities clearly look into expanding the restrictive regulation to online news media, while access to some independent websites is already restricted in Belarus. The procedures of journalists’ accreditation and laws on state secrets are used to restrict access to information. Criminal defamation and anti-extremist laws are used to curtail free speech. Despite the recent talks between Belarus’s Foreign Ministry and the Office of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, the authorities of the country remain reluctant even to discuss any possible legal reforms of the media field with civil society.

Media-related legal framework: Recommendations

The Law “On Mass Media” must be reformed, in particular:

• to secure independent self-regulation of journalism, allowing reporters of both online and offline news media, including freelance journalists, to operate freely;

• registration procedures for new media outlets should be simplified to lift all the artificial restrictions for entering the media market;

• a possibility of extrajudicial closing down of media should be eliminated; the Ministry of Information should not have the authority to impose sanctions on media, including initiating of cases of closure of media outlets.

Six articles of the Criminal Code providing for criminal liability for defamation should be abolished:

• Article 188 “Libel”

• Article 189 “Insult”

• Article 367 “Libel in relation to the President of the Republic of Belarus”

• Article 368 “Insulting the President of the Republic of Belarus”

• Article 369 “Insulting the representative of the authorities”

• Article 369–1 “Discrediting the Republic of Belarus”

Equal and full access to information should be ensured for all journalists of both online and offline media. The institute of accreditation should not be used to restrict the right to access information. In particular, the existing ban for cooperation with foreign media without an accreditation should be lifted as it contradicts the Constitution of Belarus and its international commitments in the field of freedom of expression.

Several provisions of the presidential Decree No 60 of 1 February 2010 on regulating the internet should be dropped in line with the recommendations in “Belarus: Pulling the Plug“, along with various other edicts related to the implementation of the decree. In particular, owners of websites should be free to register them at any domain and host them in any country. News websites should not be black-listed and blocked.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 13 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the second of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform.

The present media market started to take shape at the beginning of 1990s as Belarus became an independent state after the Soviet Union disintegrated. Unlike other post-Soviet states, the process of the denationalisation and privatisation of the state media was not in fact ever launched leaving state control and ownership over most of national media. While a number of independent media outlets were established in the 1990s, very few have managed to survive.

Current media are significantly affected by the political and economic situation after the presidential election of December 2010 that was followed by a severe clampdown on political opposition and civil society and periods of financial instability.

The authorities keep tight regulatory and economic control over the news media market. State-run media that are used as means of government propaganda enjoy significant financial support, while independent news media face economic discrimination that makes their position in the market more vulnerable.

Broadcast media

Broadcast media remain the primary source of information for most Belarusians. The overall reach of television is 98.4% of the population aged over 15, and its share in the media advertising market is over 50% of the total. This dominant position of television is the reason the state keeps this sphere under strict control. Most of broadcast media in Belarus are state-owned, and they enjoy significant financial support from the authorities. The state budget of Belarus for 2014 allocated 548 bn roubles (about £34m) for direct support of television and radio.

There are 262 TV and radio stations registered, 178 of them–68% of the total–are owned by the state. There is no formal Public Service Broadcaster (PSB) with an independent board and a commitment to impartiality. Four national channels are owned by the National State Television and Radio Company which also owns five radio channels and five regional TV and radio companies. Two more national channels, ONT and STV, are formally joint stock companies, but they are not publicly listed, and all their founders are state companies.

There is not a single independent national TV channel or a public service broadcaster in the country. Independent broadcast media that operates from abroad face restrictions. For instance, Belsat TV channel, which has been broadcasting in Belarusian from Poland since 2007, has been refused permission to open an official editorial office in Belarus. Belsat’s reporters face constant pressure and are subjected to warnings and detentions.

At the same time, a decision taken in November 2013 to prolong accreditation in Minsk of the editorial office of Euroradio, an independent radio station that also broadcasts in Belarusian from Poland, can be considered as a positive step.

The general process of licensing and frequency allocation in Belarus is complicated, not transparent and is controlled entirely by the government through licensing and frequency allocation processes.

Printed media

Economic leverages are used by the authorities of the country to control the printed news media market in Belarus. While state-owned newspapers have preferences in advertising market and distribution, independent publications fail to enjoy equal conditions, being restricted from distribution systems and advertising. Economic difficulties threaten operations of non-state socio-political newspapers, and thus restrict the access of the audience to independent sources of information.

The majority of printed media – 1,146 out of the total of 1,556 registered in Belarus as of 1 January 2014 – are privately owned. Most of the non-state newspapers are not news publishers but mainly advertising or publications for entertainment. According to BAJ, there are less than 30 socio-political newspapers, both national and regional, in Belarus that are publications with actual news journalism.

There is a significant amount of evidence to suggest that the non-state owned press in Belarus faces economic discrimination. Direct state subsidies to the state-owned printed media in 2014 are projected to be 64 bn roubles (about £4 m). It is claimed by the editors of several non-state newspapers, that the costs of paper and printing for independent newspapers are higher than for state-owned ones.

Another form of direct economic discrimination by the government is the influence of the state over the advertising market. The economy of Belarus is dominated by the state, with 70 per cent of its GDP being the output of state-owned companies. In practice this gives opportunities for the direct interference of the government in the distribution of advertising revenues. It is also the case that there is compulsory subscription to state-owned newspapers, both national and local, for employees of state-owned enterprises and organisations.

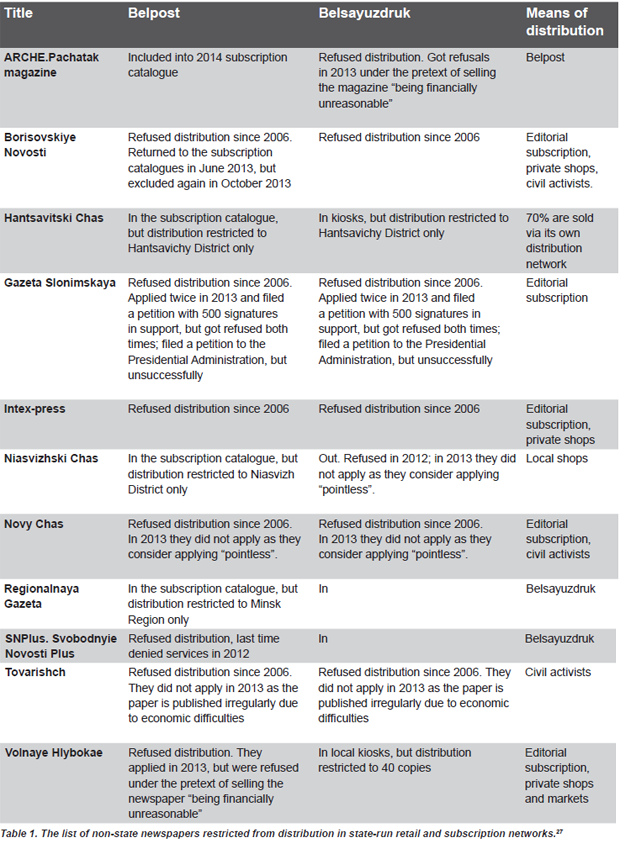

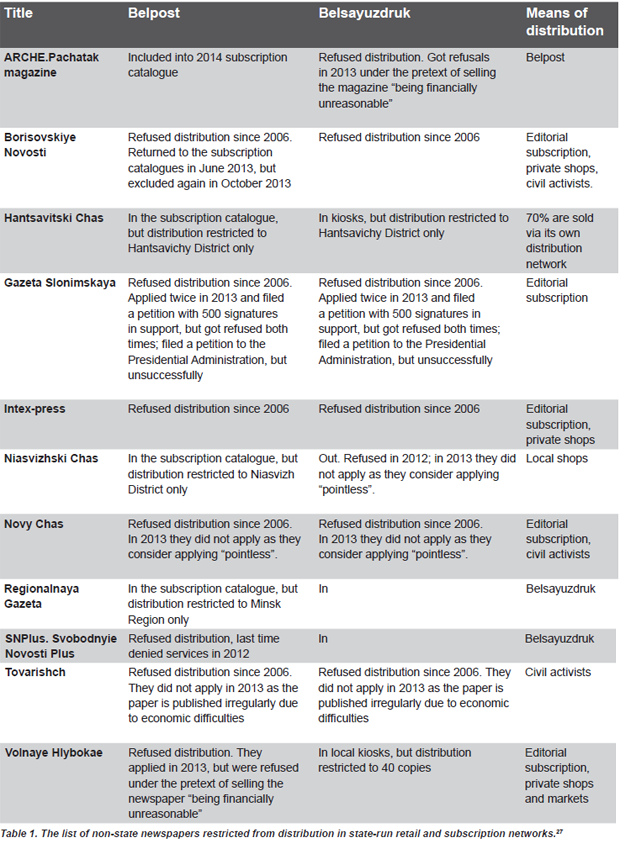

There is direct state intervention in the distribution of independent newspapers, which prevents their sale. At least eleven independent publications face restrictions to their distribution via state-run retail press distribution and subscription networks (Table 1). The distribution ban was imposed on the eve of the presidential election of 2006, when at least 16 independent newspapers were excluded from the subscription catalogue of Belposhta (Belarusian Post) and 19 had their contracts with Belsayuzdruk retail sales system cancelled. Due to the distribution restrictions several of them ceased to exist. Most of those that survived remain barred from state distributors and have had to either develop their own distribution systems or move completely online.

The authorities of the country persistently refuse to acknowledge the problem of distribution restrictions. Dzmitry Shedko, Deputy Minister of Information, wrote to Index request that “non-state media equally with state ones have a free access to state printing facilities and possibilities to distribute their publications through state press distribution structures.” The Deputy Minister points out that the law provides for the freedom of contract, and the authorities cannot interfere with the will of distribution companies to sign contracts with any particular mass media outlet.

In practice the reality is very different. In 2008 two independent newspapers, Nasha Niva and Narodnaya Volia, were returned to state distribution systems as a part of commitments the authorities of Belarus made to the European Union in order to re-launch a political dialogue with the EU. It proves a decision to lift the distribution restriction is political and can be dictated by the state.

Online media

The internet in Belarus is developing extensively, although it cannot still boast of the same audiences as broadcast media. Over 4.85 m Belarusians aged over 15 access the internet–12% more than a year ago–and over 80% of those with access go online every day. Sixty-eight percent of Belarus’s internet users go online through a high-speed broadband connection. The internet remains a relatively free domain of freedom of expression in the country, despite recent attempts by the government to put it under tighter control, as revealed in Belarus: Pulling the Plug report, produced by Index on Censorship in January 2013.

Growing internet penetration and the restrictions traditional media face offline has led to a significant development of online news media. For instance, several independent publications that stopped issuing printed versions due to distribution restrictions now only exist as websites. This is the case with Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta, once one of the leaders of non-state press, Salidarnasc or Khimik regional newspaper. Online versions of several existent newspapers reach a larger audience that their printed versions.

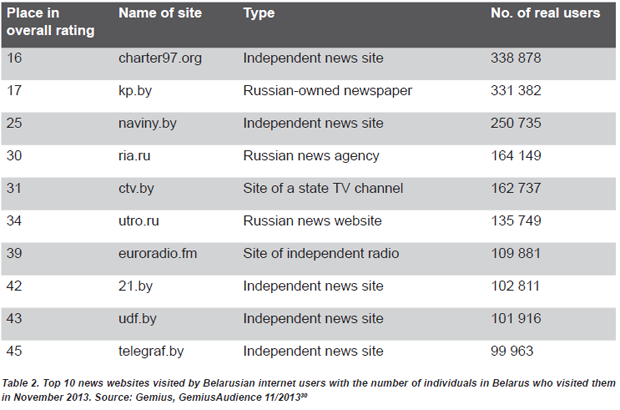

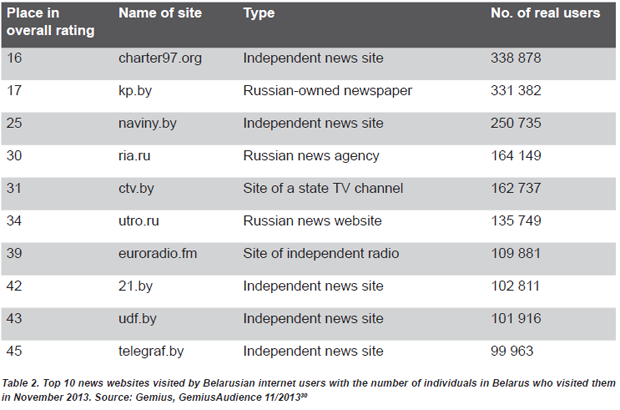

In general, independent online publications enjoy significantly greater popularity among internet users than pro-regime websites of state-run media.

This table represents online news publications only, but does not include the news sections of larger internet portals. It should be noted that they are much more popular then dedicated news publications. For instance, the news section of the largest Belarusian portal TUT.BY is visited by about 1 m Belarusians aged over 15 monthly. News sections of major Russian portals Mail.ru and Yandex.ru are ranked 2nd and 3rd as sources of online news for visitors from Belarus.

The two important trends of Belarus’s online news market are:

• Dedicated news websites are not the most popular online destinations for Belarusians;

• Russian websites have a significant market share in terms of Belarusian audience.

The top 20 news publications have a joint reach of no more than 25% of the total number of Belarusians online. If news sections of major portals are taken into consideration, this share is still around 45%. At the same time, Mail.ru, a Russian portal that is the most popular website among the Belarusian audience, has an audience share of 61.7% alone. Users appear to favour reading news on portals, where they can get other services and on news aggregators.

Social media sites are visited by 72.5% of Belarusian internet users, with Russian Odnoklassniki.ru and Vkontakte leading in this group as well. Four of the six most popular websites in Belarus are Russian portals or services.

There are serious limitations to the development of the online news media market. This is not due to government restrictions, but primarily due to economic factors. The total annual volume of the online advertising market in Belarus in 2013 is estimated to be $10.5 million US dollars. Despite 50% growth to 2012, Belarus still has one of the lowest advertising expenditure budgets per internet user in Europe. The market is very much dominated by its leaders, including Russian media companies that have significant resources to expand and currently enjoy a significant market share.

Case study: State and non-state press: Different media realities

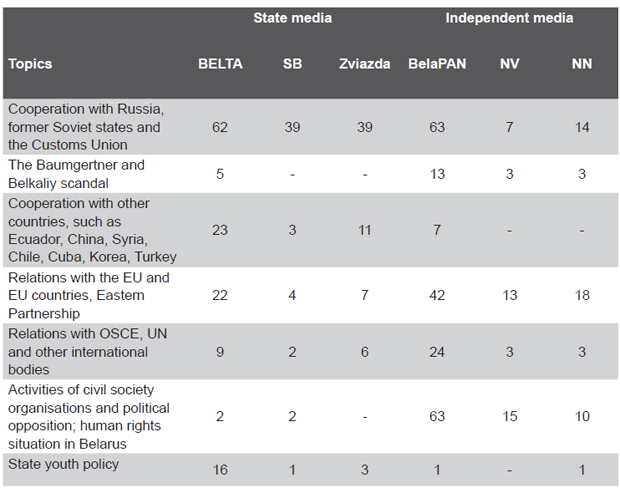

Index on Censorship in cooperation with Mediakritika.by, a Belarusian project dedicated to analysing and monitoring the national media landscape, conducted field research into the content published by state-owned and independent media (that is privately owned media that is free from political direction from the president and government). The research found clear differences between editorial policies of the media based on their ownership including the topics they cover and their approaches to coverage. The difference was particularly noticeable during major political campaigns, such as elections.

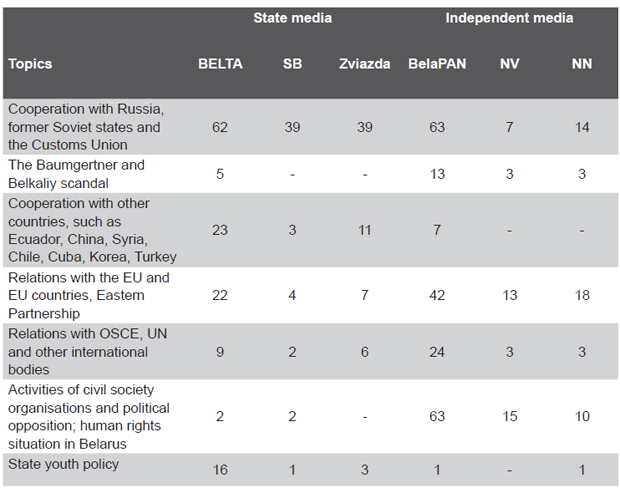

The research looked at the content of six Belarusian media outlets, analysed as presented at their websites in October 2013. They are two leading information agencies, state-owned BELTA and privately owned BelaPAN (presented online as Naviny.by), and four national newspapers, state-owned Sovetskaya Belorussiya (SB) and Zviazda, and independent Narodnaya Volia (NV) and Nasha Niva (NN).

The content was analysed in terms of presence of several specific topics (quantitative) and the way they were approached by the media (qualitative). The table below represents the number of articles covered or mentioned by the specified topics from the respective media outlets in October 2013:

On the first category, the coverage of relations with states from the former Soviet Union and the creation of a Customs Union (between Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan) which is part of the official foreign policy of Belarus, the state news agency BELTA dedicates significant coverage. BELTA also gives significant coverage to successful foreign policy partnerships by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and countries in South-East Asia and Latin America. The state media’s significant coverage of the Customs Union and relations with Russia is not matched by coverage of Belarus – EU relations. The analysis found there was little coverage of foreign policy analysis except the opinions of state officials.

The independent media also pays significant attention to the Russian – Belarusian relations, but there is significantly more coverage of Belarusian relations with the EU and other international institutions and organisations. For example, the number of news items on the “eastern” and “western” vectors produced by BelaPAN is almost the same; BELTA pays twice more attention to ex-Soviet countries, Russia first of all, than to cooperation with the West.

Even more dramatic differences are noted in the way state and independent media cover domestic politics. Within the state media politics is associated with (and consists of little more than) the statements and public speeches of the President. State media outlets even have “President” as a separate news section. BELTA’s “President” section, for instance, had more than 80 news items on activities and statements of the head of the state in October 2013.

The most significant difference between the state-owned media and the privately owned media is that there is almost no mention of the activities of the political opposition, while the independent media provides significant coverage of the activities of opposition political parties but also independent trade unions, civil society organisations and activists.

Human rights issues or repressive measures taken by the authorities are widely covered by the independent media. As can be seen in the table, the state media almost entirely ignores these issues. While the recent scandal with Vladislav Baumgertner, the CEO of the Russian Uralkaliy company, who was arrested in Minsk,34 generated significant headlines in the independent media in Belarus – and the media in Russia as well – it was hardly covered by the Belarusian state media; their coverage was reduced to quotes from President Lukashenko on the matter.

There have been no visible improvements of the situation with traditional news media since 2009 in Belarus. The state keeps dominating the broadcast media market and preserves tight control over printed publications. State-owned media are used as a tool for government propaganda, while independent socio-political press faces discrimination that limits their operational capacity and thus restricts the development of free and pluralistic media in the country. The internet re-shapes the news media market as it provides new opportunities for free flow of information and ideas, but its full-scale development as a free speech domain is hindered by economic peculiarities and attempts of state regulation.

Belarus media landscape: Recommendations

All forms of economic discrimination against non-state independent press should be eliminated, in particular:

• independent publications should be treated equally by the state system of press distribution and Belposhta subscription catalogues;

• the state has a pro-active duty to protect and promote freedom of expression and so should investigate anti-competitive practices including the charging of unequal prices for paper and the distribution services for publications for different types of ownership.

Reforms of the Belarusian media field should be launched, including de-monopolising of the electronic media, introducing public service media and creating a competitive media market. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Feb 2014 | Belarus, News

Join Index at a presentation of a new policy paper on media freedom in Belarus on 19 February, 2014, 15.00 at the Office for Democratic Belarus in Brussels.

This article is the first of a series based on the Index on Censorship report Belarus: Time for media reform

Belarus continues to have one of the most restrictive and hostile media environments in Europe.

Despite pressure from international sources recent years have brought no genuine improvements to the media situation. In a country that has not held a free or fair election since 1994, the authorities keep tight control over the media as a means of preserving their power.

The country’s media market is strictly controlled by the Belarusian government. That control rigs the media market to benefit state-owned providers and impedes the development of independent print and television outlets through legislative and administrative restrictions. The state-owned media enjoys significant budget subsidies, favourable advertising and distribution contracts with government agencies. In comparison, independent publications face economic discrimination and distribution restrictions. Field research conducted for this policy paper in Belarus found clear differences between editorial policies of the media based on their ownership including the topics they cover and their approaches to coverage.

The internet has become an important source of independent information for Belarusians. The development of online news media is hindered by the structure of the internet market, which is dominated by large portals and services, including many Russian sites. Belarusian authorities also aim at tighter regulation of internet as outlined in Index’s policy paper, Belarus: Pulling the Plug.

Restrictive media legislation and its oppressive implementation has made the media landscape unfavourable for freedom of expression. Media law forces new outlets to register and regulations give the state the power to close down media even for minor infringements. Accreditation procedures are used to restrict journalists’ access to information and foreign correspondents face additional obstacles in reporting from the country. The criminalisation of defamation, anti-extremism legislation and other laws are being used to curtail media freedom and persecute independent journalists and publishers. The police use violence and detain journalists, especially those who cover protests. Reporters are routinely sentenced to administrative arrests and fines.

Despite ongoing pressure by international bodies such as Index on Censorship, the authorities of the country have been quite reluctant to discuss or implement recommendations on media legislation or changes in practices of their implementation to bring them in line with international standards.

Index urges the Belarusian authorities to immediately remove all contraventions of human rights and media freedom. The much-needed reforms of the media field should be launched in order to end harassment and persecution of journalists, and eliminate excessive state interference in media freedom. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.

The European Union and other international institutions must place the issue of media freedom on the agenda of any dialogue with the Belarusian authorities to demand genuine reforms to bring the Belarus media-related legislation and practices of its implementation in line with the Belarusian Constitution and its international commitments in the field of freedom of expression.

****

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press is guaranteed in the Belarusian Constitution. But despite the authorities of the country stating it “has a full-fledged national information space” that “develops dynamically”, the country is one of the world’s worst places for media freedom. Belarus is listed 193 out of 197, lowest in the 2013 Freedom of the Press rating by Freedom House. Reporters Without Borders rank it 157 out of 179 countries in their 2013 Press Freedom Index.

According to Thomas Hammarberg, a former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, “free, independent and pluralistic media based on freedom of information and expression are a core element of any functioning democracy; freedom of the media is also essential for the protection of all other human rights.”

The media freedom situation and the form of the Belarusian media market are affected by the overall political situation. The media field is tightly regulated by the authorities of the country that see close control over the information sphere as their basis of preserving power. Belarus is described as “not free” in terms of political freedoms and is criticised for its overall poor human rights record. No election or national referendum in Belarus has been recognised as free and fair by OSCE ODIHR since President Alexander Lukashenko came to power in 1994. According to Belarusian human rights organisations, there are currently 11 political prisoners behind bars. The report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus suggests there are serious problems with freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, freedom of association and other fundamental rights and freedoms.

Serious concerns over profound and systemic problems with media freedom in Belarus have been highlighted on numerous occasions by the European Parliament, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, as well as civil society within the country.

“The Belarusian independent media fulfil a crucial role in the state dominated media landscape in Belarus and have been one of the main victims of the authorities’ crackdown on independent opinions after the 2010 Presidential elections,” said the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and Neighbourhood Policy Štefan Füle.

The main areas of concern are the restrictive legal framework, issues of impunity and journalists’ safety as well as the ongoing economic discrimination by the state against independent media.

Part 1 Belarus: Europe’s most hostile media environment | Part 2 Belarus: A distorted media market strangles independent voices | Part 3 Belarus: Legal frameworks and regulations stifle new competitors | Part 4 Belarus: Violence and intimidation of journalists unchecked | Part 5 Belarus must reform its approach to media freedom

A full report in PDF is available here

This article was published on 10 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Feb 2014 | Belarus, Campaigns, Index Reports

In a new policy paper, launched today in Minsk, Index on Censorship calls for the much-needed reforms of the media field in Belarus.

Belarus continues to have one of the most restrictive and hostile media environments in Europe. Recent years have brought no genuine improvements to the media situation. In a country that has not held a free and fair election since 1994 the authorities keep tight control over the media as a means of preserving their power.

The new report Belarus: Time for media reform says the country’s media market is strictly controlled by the Belarusian government. That control rigs the media market to benefit state-owned providers and impedes the development of independent print and television outlets through legislative and administrative restrictions. The state-owned media enjoys significant budget subsidies, favourable advertising and distribution contracts with government agencies. In comparison, independent publications face economic discrimination and distribution restrictions.

The police use violence and detain journalists, especially those who cover protests.

8 February 2014 will mark the 5th anniversary of the current media law in Belarus. Restrictive media legislation and its oppressive implementation have made the media landscape unfavourable for freedom of expression.

Andrei Bastunets, a vice chairperson of the Belarusian Association of Journalists, and a co-author of the report, said:

“The media law in Belarus fails to foster the development of pluralistic and independent news media through a complicated procedure of compulsory registration of new media outlets and possibilities for the state to close down existing media even for minor infringements. The authorities clearly look into expanding the restrictive regulation to online news media.”

Despite ongoing pressure by international community and Belarusian civil society, the authorities of the country have been quite reluctant to discuss or implement recommendations on media legislation or changes in practices of their implementation to bring them in line with international standards.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, Index Belarus Programme Officer, said:

“We urge the Belarusian authorities to immediately remove all contraventions of human rights and media freedom. The much-needed reforms of the media field should be launched in order to end harassment and persecution of journalists, and eliminate excessive state interference in media freedom. The outline of these reforms should result from a dialogue with professional community and civil society of the country.”

Read the full text of the policy paper “Belarus: Time for media reform” here.

Поўны тэкст аналітычнага дакладу “За рэформы медыя ў Беларусі” можна пабачыць тут.