Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

An American tells a Russian that the United States is so free he can stand in front of the White House and yell, “To hell with Ronald Reagan.’’ The Russian replies: “That’s nothing. We also have freedom of speech! I can stand in front of the Kremlin and yell, ‘To hell with Ronald Reagan,’ too.’’

Most would not associate Belarus, known in Western media for its authoritarian regime, with comedy. And it’s true that the current situation is indeed more tragic than comical. Satirical accounts on Twitter and Instagram sharing jokes and memes get designated as “extremist” and a simple like or subscription can land you in jail.

However, this is where humour has an important role and dates back to a longstanding political tradition in the Soviet Union where satire and jokes were ways to bypass censorship, serve as an antidote to official propaganda and generally not let the reality around you get you down.

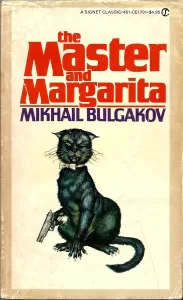

Probably the best-known book of political satire in the Soviet Union was Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, published only after the author’s death in 1966 and promptly banned, which cast Stalin in the role of the devil. As Viv Groskop wrote in her excellent re-reading of classical literature called The Anna Karenina Fix:

Probably the best-known book of political satire in the Soviet Union was Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, published only after the author’s death in 1966 and promptly banned, which cast Stalin in the role of the devil. As Viv Groskop wrote in her excellent re-reading of classical literature called The Anna Karenina Fix:

“I sometimes wonder if The Master and Margarita explains many people’s indifference to politics and current affairs. They are deeply cynical, for reasons explored fully in this novel. Bulgakov describes a society where nothing is as it seems. People lie routinely. People who do not deserve them receive rewards. You can be declared insane simply for wanting to write fiction. The Master and Margarita is, ultimately, a huge study in cognitive dissonance. It’s about a state of mind where nothing adds up and yet you must act as if it does. Often, the only way to survive in that state is to tune out.”

Similarly, in 1980 the Czech-French novelist Milan Kundera said: “I learned the value of humour during the time of Stalinist terror. I could always recognise a person who was not a Stalinist, a person whom I needn’t fear, by the way he smiled. A sense of humour was a trustworthy sign of recognition. Ever since, I have been terrified by a world that is losing its sense of humour.”

In the Soviet Union Brezhnev jokes were especially popular, making fun of his stumbling, often incoherent speech, public mishaps and penchant for kissing other political leaders on the mouth.

Often he was made fun of as a totally useless leader. Take this joke that circulated at the time:

Lenin proved that even female cooks could manage a country.

Stalin proved that just one person could manage a country.

Khrushchev proved that a fool could manage a country.

Brezhnev proved that a country doesn’t need to be managed at all.

Or this:

With Lenin, it was like being in a tunnel: You‘re surrounded by darkness, but there’s light ahead. With Stalin, it was like being on a bus: One person is driving, half the people on the bus are sitting [“sitting” in Russian having a secondary meaning of doing time in prison] and the other half are quaking with fear. With Khrushchev, it was like at a circus: One person is talking, and everyone else is laughing. With Brezhnev, it was like at the movies: Everyone’s just waiting for the film to end.

This tradition has certainly continued in Belarus with Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who likes to refer to himself as “bat’ka” in Belarusian or a “father of the nation”. People mock him both for his poor knowledge of Belarusian, which he uses in combination with Russian, and his wannabe macho appearances and pronouncements.

One of the most well-known Belarusian stand-up comics, Slava Komissarenko, went viral and became famous overnight when he made fun of Lukashenka’s Rambo-like appearance with a gun at the height of the 2020 protests, ready to defend the presidential palace from completely peaceful protesters who were just standing there. Lukashenka made a ‘heroic’ dash from the helicopter and then brandished guns, which he waived at the protesters before hurriedly disappearing inside flanked by security. Numerous memes emerged after to spoof the moment.

Komissarenko had himself joked about Lukashenka already, back in 2015. These often innocent barbs were still considered dangerous enough for state television to cut them out. Back then, for example, he said: “Recently we had presidential elections. Surprising, isn’t it? The fact that there are elections. Everyone thought it is a lifetime job. He got 85.3 %. I think he can do better. But it’s not his last time, only fifth.”

After his 2020 stand-up authorities evoked his licence (“I know from where the only dislike under my YouTube video came from,” he joked.) Later he was forced to leave the country. First he went to Kyiv and when the war started on to Warsaw where he is based now along with other politically critical comedians. It’s from there they run their shows. Komissarenko’s Instagram account is followed by more than 670,000 people and his YouTube videos routinely gather millions of views and likes.

Another humorous X/Twitter account that recently caught the attention of authorities, who again deemed it “extremist”, is “Sad Kolya”, under the @sadmikalai handle. It impersonates Lukashenka’s son Kolya, who tweets about his daddy and the misfortune of being his son. “Papa called Prigozhin who assured him that he had been killed” one of the recent ones reads. Another: “I hope my dad runs out before my passport.”

During the protests it was a great source of comfort and relief to read these humorous one-liners. The avatar on the account has both Belarusian and Ukrainian flags in solidarity with Ukraine, and the cover photo features a real photo of Kolya standing between Putin and Lukashenka.

When the war started in Ukraine some of the memes that got incredibly popular made fun of Lukashenka and the statement he made on state TV, where he promised to show everyone “where Belarus was going to be attacked from” by Ukraine. One meme put him in various situations endlessly repeating this phrase to everyone’s exasperation. Another meme looked like a screenshot from a WhatsApp chat with the avatar of Lukashenka texting in the middle of the night as if to his girlfriend. “Are you asleep? Just wanted to show you where Belarus was going to be attacked from”.

The Belarusian stand-up scene is now mostly active in Warsaw and Vilnius, with occasional tours abroad. In Belarus those who stayed (about 30 stand-up comics) cannot talk about politics at all and the material needs to be sent to the Ministry of Culture for approval before the show. They stick to safer topics of dating and other things that make living under dictatorship more or less bearable. But the politics still can sneak in. Just recently Komissarenko himself unexpectedly became the subject of jokes when some details about his new wife’s saucy past were revealed.

“I feel for you” wrote one of the commentators on social media. “My friend recently married a guy and it turned out he likes Shaman [a nationalist Russian singer loved by the Kremlin]. So remember it could have been much worse!!!”

Januskevic Publishing House opened for business in Belarus in 2014 with the aim of publishing history books. The initial euphoria of launching a business passed very quickly.

At first, issues related to the publishing industry more broadly. It became clear that you can’t live in Belarus only publishing history books – diversification of production was required. So we diversified into e-books and then to the publication of fiction, translations from foreign languages and children’s books. We did have some good years. Between 2017 and 2022 we developed quickly. We even founded our own online bookshop. Our mission always was to make books that are interesting to the reader. We had a broad slogan: We make books that you want to read.

But after the re-election of long-time Belarus president Alyaksandr Lukashenka in 2020 and his subsequent violet crackdown on protests, and after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the troubles started. In literally three days we were kicked out of the office that had served us as a showroom and a pickup point for books. We were left without a home.

We soon managed to open a fully-fledged bookshop that would serve us as an office at the same time. Except the expulsion from our original office was not some spontaneous decision. It was a deliberate signal. On the day of the opening of the Knihauka bookshop on 16 May 2022, propagandists from state mass media outlets and officers from HUBAZiK (Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption) turned up. The HUBAZiK said that extremist literature was being sold in our bookshop and, with a prosecutor`s approval, they checked all the books in the shop and seized 15 items. Why these specific ones? I’m not entirely sure, although there was a certain theme through them. They were all by Belarusian authors, all history or nonfiction and some children’s books, like Iosif Brodsky’s book The Ballad of the Tugboat.

In an even worse twist bookshop employee Nasta Karnatskaya and I were arrested. I spent 28 days in jail – three terms for three court rulings – and Nasta spent 23 days in jail. This is the only case where somebody was apprehended and imprisoned for distributing books.

While it was challenging before, the radicalisation of the government’s actions against culture, and against the publishing business in particular, gained speed after Russia’s attack on Ukraine

After being released, I realised that the publishing house could no longer work as it had. There was the external pressure that manifested itself in these arrests, as well as other pressures: literally the day after the closing of the bookshop, for the first time in Belarus’ history, the celebrated fiction book The Dogs of Europe by Alhierd Bacharevič, which was published by us and turned into a play staged throughout the world, was deemed “extremist material”. This was a very bad sign. We were moving towards a point where the publishing house itself could be recognised as extremist. I knew then that it was dangerous to stay in Belarus. It was becoming too dangerous to make books. And so we left Belarus and opened up shop in Poland.

It was definitely the right decision. Our publishing license was revoked from us in early January 2023. This was carried out by a court for the first time in Belarus` history according to the provisions of the Law of the Republic of Belarus On Publishing, with the reason given that we had systematically published literature which later was included in the list of extremist materials. To date, four books by our publishing house have been recognised as extremist.

The treatment we received was part of a systemic attack against the independent publishing sector in Belarus. It was not only us who were targeted. Other Belarusian publishing houses were and are victims. Haliyafy, for example, was forced to initiate bankruptcy proceedings. Knihazbor, despite its attempt to remain on its feet and resume its activities, was also forced to close. Today it’s impossible to work freely and to define one’s own publishing policy in Belarus.

In January 2023, we were stripped of our publishing licence. Since then, we have been not allowed to publish books in Belarus.

Following this, on 20 January I set up a fully-fledged publishing house functioning as a Polish legal entity. Since then we have published more than 20 books in Belarusian and we mail books to Belarus. You could argue that our forced relocation from Belarus to Poland has been successful.

But while I still have a licence to distribute books in Belarus and I could sell those I published earlier, almost no one takes them for sale because I have a black mark. These are the consequences of total fear in a society.

Of those publishers who left Belarus, no others continue publishing. They’re now engaged in other businesses: some have switched to writing, for example.

New publishing houses have appeared in Belarus and are managed by new people. Those who remain in Belarus are not publishing books with any strong social implications. I see that when something appears it is "neutral" literature or aimed at children. Those who suffered repression have left their businesses because there are simply no opportunities for their activities in Belarus. Either you have to work in line with the government policy, or you just don’t work.

While it was challenging before, the radicalisation of the government’s actions against culture, and against the publishing business in particular, gained speed after Russia’s attack on Ukraine. Now all kinds of barriers have disappeared for Belarus authorities in the last year – they simply do what they want.

As for wholesale deliveries of foreign publishing houses to networks of booksellers in Belarus, there have been none at all from anywhere except Russia.

Indeed, since February 2022 Belarus has become part of the "Russian World", a part of the cultural policy which turns Belarus into a Western province of Russia. The prospects for the development of Belarusian culture, the Belarusian language and the Belarusian book industry under Lukashenka are very grim. It will be an imitation, paint-by-numbers culture based on folklore and ethnography. Nothing more, I’m afraid.

A first English translation of a new short story, "Punitive Squad", by Alhierd Bacharevič, is published in the winter edition of Index on Censorship. This article first appeared in The Bookseller.

The Winter 2023 issue of Index looks at how comedians are being targeted by oppressive regimes around the world in order to crack down on dissent. In this issue, we attempt to uncover the extent of the threat to comedy worldwide, highlighting examples of comedians being harassed, threatened or silenced by those wishing to censor them.

The writers in this issue report on example of comedians being targeted all over the globe, from Russia to Uganda to Brazil. Laughter is often the best medicine in dark times, making comedy a vital tool of dissent. When the state places restrictions on what people can joke about and suppresses those who breach their strict rules, it's no laughing matter.

Still laughing, just, by Jemimah Steinfeld: When free speech becomes a laughing matter.

The Index, by Mark Frary: The latest in the world of free expression, from Russian elections to a memorable gardener

Silent Palestinians, by Samir El-Youssef: Voices of reason are being stamped out.

Soundtrack for a siege, by JP O'Malley: Bosnia’s story of underground music, resistance and Bono.

Libraries turned into Arsenals, by Sasha Dovzhyk: Once silent spaces in Ukraine are pivotal in times of war.

Shot by both sides, by Martin Bright: The Russian writers being cancelled.

A sinister news cycle, by Winthrop Rodgers: A journalist speaks out from behind bars in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Smoke, fire and a media storm, by John Lewinski: Can respect for a local culture and media scrutiny co-exist? The aftermath of disaster in Hawaii has put this to the test.

Message marches into lives and homes, by Anmol Irfan: How Pakistan's history of demonising women's movements is still at large today.

A snake devouring its own tail, by JS Tennant: A Cuban journalist faces civic death, then forced emigration.

A 'seasoned dissident' speaks up, by Martin Bright: Writing against Russian authority has come full circle for Gennady Katsov.

And God created laughter (so fuck off), by Shalom Auslander: On failing to be serious, and trading rabbis for Kafka.

The jokes that are made - and banned - in China, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Journalist turned comedian Vicky Xu is under threat after exposing Beijing’s crimes but in comedy she finds a refuge.

Giving Putin the finger, by John Sweeney: Reflecting on a comedy festival that tells Putin to “fuck off”.

Meet the Iranian cartoonist who had to flee his country, by Daisy Ruddock: Kianoush Ramezani is laughing in the face of the Ayatollah.

The SLAPP stickers, by Rosie Holt and Charlie Holt: Sometimes it’s not the autocrats, or the audience, that comedians fear, it’s the lawyers.

This great stage of fools, by Danson Kahyana: A comedy troupe in Uganda pushes the line on acceptable speech.

Joke's on Lukashenka speaking rubbish Belarusian. Or is it?, by Maria Sorensen: Comedy under an authoritarian regime could be hilarious, it it was allowed.

Laughing matters, by Daisy Ruddock: Knock knock. Who's there? The comedy police.

Taliban takeover jokes, by Spozhmai Maani and Rizwan Sharif: In Afghanistan, the Taliban can never by the punchline.

Turkey's standups sit down, by Kaya Genç: Turkey loses its sense of humour over a joke deemed offensive.

An unfunny double act, by Thiện Việt: A gold-plated steak and a maternal slap lead to problems for two comedians in Vietnam.

Dragged down, by Tilewa Kazeem: Nigeria's queens refuse to be dethroned.

Turning sorrow into satire, by Zahra Hankir: A lesson from Lebanon: even terrible times need comedic release.

'Hatred has won, the artist has lost', by Salil Tripathi: Hindu nationalism and cries of blasphemy are causing jokes to land badly in India.

Did you hear the one about...? No, you won't have, by Alexandra Domenech: Putin has strangled comedy in Russia, but that doesn't stop Russian voices.

Of Conservatives, cancel culture and comics, by Simone Marques: In Brazil, a comedy gay Jesus was met with Molotov cocktails.

Standing up for Indigenous culture, by Katie Dancey-Downs: Comedian Janelle Niles deals in the uncomfortable, even when she'd rather not.

Your truth or mine, by Bobby Duffy: Debate: Is there a free speech crisis on UK campuses?

All the books that might not get written, by Andrew Lownie: Freedom of information faces a right royal problem.

An image or a thousand words?, by Ruth Anderson: When to look at an image and when to look away.

Lukashenka's horror dream, by Alhierd Bacharevič and Mark Frary: The Belarusian author’s new collection of short stories is an act of resistance. We publish one for the first time in English.

Lost in time and memory, by Xue Tiwei: In a new short story, a man finds himself haunted by the ghosts of executions.

The hunger games, by Stephen Komarnyckyj and Mykola Khvylovy: The lesson of a Ukrainian writer’s death must be remembered today.

The woman who stopped Malta's mafia taking over, by Paul Caruana Galizia: Daphne Caruana Galizia’s son reckons with his mother’s assassination.

It is important the international community pays close attention to the scale of politically motivated persecutions in Belarus, a panel discussion organised by the media organisation Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty recently said.

It was after Zmitser Dashkevich, a well-known Belarusian activist originally charged with extremism, had his sentence extended by a year after being charged with "blatantly disobeying penitentiary guards". His sentenced was due to end in July. Journalist Andrei Aliaksandrau, a former employee of Index, recently spent his 1000th night behind bars after being imprisoned for 14 years in October 2022 for “extremist activities” against the state.

Anastasiia Kruope, assistant researcher for the Europe and Central Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, said there has been a large increase in human rights abuses and politically motivated persecutions in Belarus following Aleksandr Lukashenka's heavily contested presidential election win in 2020.

“An atmosphere of fear and intimidation for journalists and human rights defenders was created,” she added.

“The way these people are treated in prisons and labelled extremist, along with the silencing of family members outside, means some of these cases may amount to crimes against humanity according to the UN.”

Aleh Hruzdzilovich was one such prisoner. A journalist for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, he spent nine months in prison and was released in September 2022. After covering the protests following Lukaskenka’s re-election for his job, he was arrested and charged with actively taking part in them.

“From the very first day, people like me recorded as extremists are punished more and have a stigma in prison,” Hruzdzilovich explained.

“It means we’re put in punishment cells and solitary confinement more often. When I was tortured, I was told to sleep on the wooden floor. If I simply sat down or stopped walking around the cell in the daytime, I was reported and given more time in the punishment cell.”

Hruzdzilovich described seeing a prisoner wet himself through fear of being sent to a punishment cell.

Pavel Sapelko is a lawyer based at the Viasna Human Rights Centre in Minsk, Belarus. He said there is an absolute power of prison authorities over prisoners in Belarus, which is affecting their human rights, and seemingly makes people “disappear”.

“The prisoners are simply incommunicado. The authorities can shut down visits and calls from families, and even then can only get help from a lawyer after their sentences are passed by law.”

Speaking of the legal system in Belarus, Sapelko described the debilitating change that has occurred over the past three years.

“We’ve lost more than 300 defence lawyers, with 100 of them being disbarred. Licences have been revoked, and six defence lawyers are actually behind bars, now prison inmates themselves,” he explained.

“This massively affects a lawyer willing to take on your case, especially for those charged with being extremists.”

Ending with another reason why the international community should support those journalists and human rights defenders still in Belarus with things such as legal help and visas, Kruope had one eye on the future.

“They have the connections to document these abuses. The powerful tool we have is accountability, and it may take many years for abusers to face justice. We can focus on preserving the evidence against these abuses and document them for the future.”

Please read about Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners here, which is a collaborative project by Index on Censorship in partnership with Belarus Free Theatre, Human Rights House Foundation and Politzek.me.