Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Huang Xueqin is an activist and journalist who has worked with several domestic Chinese media outlets. She has reported extensively on the MeToo movement in China.

Huang Xueqin played a significant role in covering the MeToo movement. In 2017, she surveyed hundreds of female journalists across 15 provinces in China on their experience of workplace sexual harassment. She published her findings in a report in March 2018. She also assisted Luo Xixi, one victim of sexual harassment, to publicly submit a complaint against her professor. Her work sparked national discussions on sexual harrassment on campuses.

Huang has worked to promote women’s rights, and to document and expose sexual harassment against women and girls. Unfortunately, she has faced legal challenges because of her work as an activist and journalist. She was detained between October 2019 and January 2020 and charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” after writing about mass protests in Hong Kong.

On 19 September 2021, Huang disappeared and stopped responding to phone calls from family and friends. Two months later, in November, it was confirmed that she had been detained along with labour activist Wang Jianbing and charged with “inciting subversion of state power”. She was due to travel to the UK to study development studies at the University of Sussex after receiving a Chevening Scholarship. She remains in detention and is now held in the No. 1 Detention Centre in Guangzhou.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Former Chinese leader Hu Jintao. Credit: Roman Kubanskiy/Wikimedia Commons

Footage of China’s last leader, Hu Jintao, being removed from Beijing’s Great Hall stage during the twice-a-decade Communist Party Congress on Saturday has drawn global attention. It was a moment of drama in an otherwise tightly choreographed event. Hu, who had been seated at the front next to China’s current leader Xi Jinping, looked visibly confused as he was escorted away by two men. At one stage he tried to speak to Xi and even take some papers that were in front of him, only to be gently but firmly batted away. People quickly asked, what exactly just happened? Here is what we know:

Who exactly is Hu?

The man at the centre of the action, Hu Jintao held the highest office of the Chinese Communist Party between 2003 and 2013. While some aspects of free expression did constrict under his rule, he was largely seen as a moderate force, open to new ideas and the outside world. LGBTQ+ and women’s rights certainly gained ground under Hu. Xi Jinping’s rule has been markedly different, defined by anti-corruption campaigns sniffing out past cronyism and a sweeping attack on the central pillars of civil society.

What did Hu say to Xi?

The key to unlock the mystery. Sadly, no Mandarin-language lipreaders have come to the fore.

Was Hu ill?

Many people were quick to ask whether Hu, 79, was just poorly. It’s also the line that China’s official news agency Xinhua has run with. He had appeared slightly unsteady the Sunday before, during the opening ceremony of the congress, when he was assisted on to the same stage. But the evidence stops here. Beyond looking a bit confused as he walked away (fair enough), he had no visible signs of illness. There were also no paramedics, and no one made any effort to help him. One of the people pictured ushering Hu out is also believed to be Xi’s own bodyguard.

If he wasn’t ill, what happened?

Most people now suspect it was orchestrated by Xi to send a message: any challenge to my rule – real or figurative – will not be tolerated. This is a new era. The old guard, whose influence had still somewhat lingered, are now well and truly out. And no one represented the old guard more than Hu, who incidentally obeyed the two-term limit which Xi has since overturned.

Would Xi be that ruthless?

Yes, he’s purged his party of all but loyalists, presided over the biggest crushing of dissent since Mao Zedong and has orchestrated a genocide against the Uyghur people. He doesn’t play nice.

Can you be certain this was what happened to Hu?

No, and we probably never will fully know. China’s elite party politics have always been defined by opacity and the broader environment is censored to the max. Any mention of the incident has been quickly scrubbed from online and people inside the room won’t talk.

What does this all mean then?

It’s not good. What little freedoms are left in the country look more precarious by the day. As author of The Great U.S.-China Tech War, Gordon G. Chang, commented straight after: “Hardliners are in and reformers are out of the #CCP’s Central Committee. #HuJintao, #XiJinping’s predecessor, was escorted out of the 20th National Congress, apparently against his will. If you’re still in #China, whether you are #Chinese or a foreigner, you should leave, now.” That might sound like hyperbole, but as mentioned above Xi is a ruthless leader.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”119624″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]On the east coast of the USA around 100 children have sent postcards to a man they do not know who is incarcerated over 8,000 miles away. The man is Jimmy Lai, the Hong Kong media mogul and activist.

The postcards have provided a brief ray of light in an otherwise dark chapter for a man locked up for his political beliefs, and the city state of Hong Kong which is currently in the ever-tightening grip of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Lai is imprisoned on charges most us will, hopefully, never have to face. The billionaire publisher and founder of Apple Daily has been jailed since December 2020 after he lit a candle during a public commemoration of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

The charges were related to this and his other pro-democracy protests. He is perhaps the most high-profile victim of the National Security Law, which was passed in the summer of 2020 with the precise aim of punishing and stifling dissent. This month he faces a trial without jury, where he will plead not guilty to the national security charges.

April Ponnuru’s daughter with the postcards.

April Ponnuru has organised the campaign on behalf of The Committee For Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation (CFHK). It was her idea for children at her daughter’s school, in Virginia, to send supportive postcards to Lai after learning he is a devout Catholic.

“My children are in a Catholic school and are Catholic, and I was thinking about how Catholics believe in the idea called corporal works of mercy, and they are these physical acts we do for people that import a lot of grace and mercy, and one of those is visiting the imprisoned,” she said.

She explained how Lai being persecuted for his ideas and belief – not only political but also regarding his faith – inspired her to contact her children’s school.

“This is a great example for these kids of somebody who stood up for their faith and is suffering unjust consequences for that. I thought they could write postcards to Jimmy and tell him they know a little bit of his story, and they’re praying for him and admire him.”

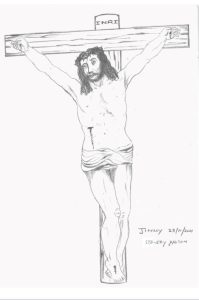

Lai is currently held at Stanley Prison, a maximum-security facility in Hong Kong where he has spent time in solitary confinement. Already a believer, he has found strength through his faith. A drawing of Jesus Christ on the cross done by Lai from prison was printed on the postcards the children sent.

This drawing was originally published in Index on Censorship’s spring 2022 magazine, alongside letters of his, many of which reference his faith.

Ponnuru said: “We thought it would be nice to include some religious art by Jimmy, and it would be a really meaningful thing that this art he sent out in the world would come back to him from a lot of children. For the children it was a great way to participate in corporal works of mercy that they ordinarily wouldn’t be able to do so. By sending him a card and message, they are visiting him.”

Jimmy Lai’s drawing of Jesus Christ.

She is eager to point out that she wants any child to have the opportunity to send a postcard, as the message of the project should not be defined just by Catholicism.

“This isn’t limited to Catholic schools. We would love any child to participate, children of all faiths and no faith. It’s about understanding the injustice of what is happening to Jimmy and others in Hong Kong. This pilot programme is just the beginning, and we would be very happy to create a postcard that would be appropriate for students at public and other schools to send as well,” Ponnuru said.

“Overall, a number of people have said to me they would love to bring it to their school, and priests have told me they are interested in copying the programme. We are going to write to other schools to encourage them to join the project.”

It’s understood the postcards were received in prison within three months of being sent, and that Lai is being allowed to read one daily, enabling him to have regular contact with the outside world.

If you would like more information about the project, and to request postcards for Jimmy Lai, please contact [email protected].[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

BBC Broadcasting House. Photo: Peter Hastings, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

This week I had planned to write about the importance of public service broadcasting. To focus on and celebrate 100 years of the world’s oldest national broadcaster, the BBC. I wanted to talk about my favourite programmes and highlight their successes and importantly their failures – because we should always have an honest appraisal of even those entities which we rely upon. But there is a bigger issue at play – in a world of disinformation and misinformation, where conspiracy feels like it’s becoming the norm we have never needed independent and publicly funded news outlets more.

Call me biased but the BBC is the best in the world and needs to be cherished and protected. Its journalists have been on the frontline of every new story for a century. They have documented every joy and every horror, without fear or favour. Because of them we have historical evidence of war crimes, of the Holocaust, of protests, of the rise and fall of governments in every corner of the world and of course the moments of global jubilation and joy.

I, for one, will always defend the institution of the BBC – it’s central to my daily life and I trust their output. I make no apologies for loving the BBC – but it’s not just the institution – it’s the promise of independent journalism, of being able to hold the powerful to account and of documenting events for posterity.

This week we have seen the value of public service journalism. In Manchester the BBC documented a democracy protester being dragged into the Chinese consulate by CCP officials. He was beaten. His story is now known and the subject of a diplomatic incident because the BBC covered the news. Bob Chen will have justice, or at least be protected because his story was told by independent journalists.

Contrast that with events in Russia. Protest is banned. Independent journalism all but crushed. Dissidents are arrested every day. Challenge is not tolerated. Their leaders never questioned.

I am so lucky to live in a democracy. To be blessed with a free press. To be able to hold my politicians to account.

Public broadcasting is integral to that – so Happy Centenary BBC – we’re lucky to have you.