Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

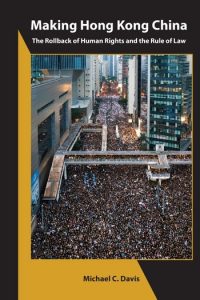

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

That moment is where this narrative begins. It is the story of a city whose people, since the handover in 1997, have felt the full catalog of emotions inspired by the onslaught of authoritarianism—anxiety, hope, despair, trepidation, and fear. Anxiety has always been part of Hong Kong’s handover story. Hope rose both from the signing of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and the passage of the 1990 Hong Kong Basic Law, as well as from later widely-supported popular protests for political reform. Despair was fueled by Beijing’s ignoring of such popular demands. Trepidation stemmed from the violence on the streets and a worry that Beijing might respond with heavy-handed repression. Fear is what has now settled on the community.

One year after the protests began, and twenty-three years after the handover, 2020 has given way mostly to a level of fear, unseen before in Hong Kong, about the future. At the center of it all is anxiety about the arrest of anyone who might have once dared to speak up, brought on by the new national security law. Beijing’s direct intervention has exposed its profound distrust of Hong Kong’s institutions, as it installs various direct controls at all levels of the criminal justice process, including the executive, the police, the Justice Department, and the courts. This intervention has brought a chill to Hong Kong’s much vaunted rule of law, its dynamic press, its world-class universities, and its status as Asia’s leading financial center.

This chilling effect is especially dramatic because of Hong Kong’s long-established status as the freest economy in Asia and the world. This freedom, however, is not limited to economics: there are many dramatic distinctions between life in Hong Kong and life on the mainland. These differences have breathed a very distinct identity into Hong Kong, and they have driven the passions that have exploded in the Hong Kong protests.

In fact, it is this very freedom that China sought to preserve with the “one country, two systems” model embodied in the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, which was enacted to carry out the 1984 treaty. This is a point that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have long forgotten, as a lack of political will to uphold these commitments has taken over.

But to understand what is now lost for Hong Kong and the world, we must acknowledge what this city long had, and how it differed from the systemic repression in mainland China. Perhaps the most celebrated distinction is Hong Kong’s annual vigil of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen massacre in Beijing. Hong Kong was long the only place on Chinese soil where such a remembrance was permitted—at least until 2020, when it was disallowed due to the coronavirus pandemic. I have attended most memorials since that violent day in 1989. And now, I fear that a similar fate by another means awaits those who continue to ardently defend their city’s dying democracy. For Hong Kong, this fate may arrive by a slow burn instead of tanks in the street, but the destination may be the same.

…..

For the first time in my thirty years of teaching human rights and constitutionalism at two of Hong Kong’s top universities, the contents of my syllabus might be cause for arrest or dismissal. Every year I have lamented that my course was illegal just thirty miles away on the mainland, joking wryly with my students that one of the starkest differences between Hong Kong and the mainland is found in our classroom. The entire syllabus is prohibited on the mainland by China’s famous Document 9, which forbids promoting topics like constitutionalism, the separation of powers, and Western notions of human rights.

Many in the academy now wonder whether this national security law brings something akin to Document 9 to Hong Kong. A rash of dismissals of Hong Kong secondary teachers for supporting the 2019 protests had already raised concern that only a syllabus friendly to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) can now be taught, or that teachers who differ with such directives will soon be exposed. Will such pressures threaten the global preeminence of Hong Kong’s universities, with several now ranked among the top fifty in the world? Will professors who speak up, or who freely teach sensitive topics, and encourage or inspire dedication to the same, risk arrest or dismissal under the new law? …

Looking beyond academics, Hong Kong’s legal profession has special cause for concern with the changed conditions under the new law. Several changes strike at the very heart of Hong Kong’s rule of law. Hong Kong has long had a very active and progressive bar, which has recently expressed deep concern about the new national security law. The Hong Kong Law Society, the membership organization of solicitors under Hong Kong’s divided profession, has also had many active human rights defenders.

Both law associations are right to be concerned. On July 7, 2015, in the so-called 709 Incident, Chinese authorities on the mainland rounded up around 250 lawyers, advocates, and other human rights defenders. The bulk of them were charged under China’s national security laws, either with “subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” and possibly incitement of the same. These lawyers, who were generally found guilty, were mostly organizing and providing legal defense to human rights activists and protesters. … Will the mainland system regarding the treatment of human rights defenders now come to Hong Kong under the heading of national security?

Groups of Hong Kong lawyers have been providing pro bono or low-cost defense of the many protesters who were arrested in 2019. A progressive lawyers’ group has also politically advocated against human rights violations in relation to the protests. What risks do these lawyers face?

The new national security law raises a host of concerns for national security trials. Under the new law, only a select panel of judges are allowed to try national security cases locally, and those judges can be dismissed from the select list of national security judges if they make statements that are thought to endanger national security. …

The gaping differences with the mainland, easily discernable to the casual observer, of course, go well beyond street protests and academics or the law and lawyers. These differences touch ordinary people’s lives in many ways. Before the new national security law was passed, a bookstore or bookfair in Hong Kong could have a full selection of books commenting on local or global affairs or even criticizing China’s leaders. Such books, including an earlier one of my own, were all banned on the mainland, though the tendency of mainland companies to own most local bookstores in Hong Kong already imposed self-censorship.

Nevertheless, pretty much any book or reading source could be obtained either in stores or online. The availability of a wider selection of books was long an attraction for mainland tourists who would then have to figure out how to smuggle them home. Within a week of the passage of the new national security law, public libraries in Hong Kong were already removing sensitive books from the shelves, and schools were being told to ban certain forms of protest speech.

…

These freedoms and much more are now at stake under the national security law. This new fear was clearly understood, when just hours before the new national security law went into effect, several organizations, including an activist group called Studentlocalism and the prominent local political party, Demosisto, disbanded. Demosisto had planned to run candidates for the Legislative Council in the coming September 2020 election. The party’s alleged sin was its earlier—and later dropped—promotion of self-determination for Hong Kong. Compared to those few who advocated for independence, this is a moderate position. Four former members of Studentlocalism would later be arrested, allegedly for organizing a new pro-independence group and calling for a “republic of Hong Kong.”

Though it was not introduced as such, the new national security law is effectively an amendment to the Hong Kong Basic Law. Like the Basic Law, it expressly provides for its own superiority over all Hong Kong’s local laws. It is also seemingly superior, where any conflicts exist, to the Hong Kong Basic Law. The Basic Law and the national security law are both national laws of the PRC. Under principles contained in the PRC Legislative Law, a national law that is enacted later in time and that is more specific in content is superior to an earlier, more general national law. Independent of such legal niceties, a local Hong Kong court would be in no position to declare any part of the new national security law invalid for being inconsistent with the human rights guarantees in the Basic Law.

Earlier, when a Hong Kong court had the temerity to declare invalid a government ban on the wearing of face masks, which protesters were wearing during the 2019 demonstrations to hide their identity, officials in Beijing immediately slammed the court. They declared that there was no separation of powers in Hong Kong and thus no basis for the judicial review of legislation—a claim long disputed by local judges. Intimidation was clearly intended and the court of appeals backed off, reversing the trial court and upholding most of the ban. In an ironic twist, with the pandemic in 2020, masks are required to be worn in public areas.

Such constitutional judicial review, long a bedrock of the Hong Kong legal system, has frequently come under mainland official threat. In the national security law, Beijing has again demonstrated its distrust of the Hong Kong courts by expressly assigning the power to interpret the new law to the standing committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), and by blocking judicial review of national security officials.

With this new national security law incorporated into the Basic Law fabric, Hong Kong effectively has a new hardline national security constitution. No heed was taken of the deep concerns about the city’s evolving character expressed eloquently by millions of Hongkongers marching through Hong Kong’s sweat-drenched streets in the summer of 2019.

Michael C. Davis is visiting professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Hong Kong, where he teaches core courses on international human rights. His book Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law is published this November by Columbia University Press.

It assesses the current state of the “one country, two systems” model that applies in Hong Kong, juxtaposing the people’s inspiring cries for freedom and the rule of law against the PRC’s increasing efforts at control. Chapters look at the constitutional journey of modern Hong Kong, discussing the Basic Law; Beijing’s interventions and the recent historical road to the current crisis; Beijing’s increased interference leading up to the 2019 protests; the 2019 protests and growing threats to the rule of law; the national security law launched in mid-2020; international interaction and support; and finally, the current status of Basic Law guarantees as they may shape the road ahead. Click here for more on the book.

…[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Nelson’s Column, photo: Steve Bidmead/Pixabay

I love journalism. I am addicted to the news and honestly anything that isn’t about the appalling pandemic we are currently living through is usually welcome. But, and it’s a big but, there are some news stories which we know are designed to inflame, to spark a reaction, to act as click-bait and they may or may not always tell the full story. To the uninitiated, they can serve as an excuse to launch a new campaign – to protect our free speech, to launch a ‘culture war’, to drive divisions in our country, so it is incumbent on all of us to explore all sides of a story and try and unearth the truth before we get caught up in the latest clicktavist campaign…

That was definitely the case at the beginning of this week, when Lord Nelson entered the fray – apparently, his role in our national story was under threat, his hero status revoked – because of his links to colonialism and support for slavery. Defence of his reputation would now be the front line in the culture wars. However, it seems that the reality is, as ever, a little more complex.

No one, not even some of our greatest heroes and heroines, is perfect. Those that did extraordinary things for our country may also have held personal views that we would rightly find repugnant today. It serves no one for us to venerate our national heroes as saints; they weren’t, they were just people, extraordinary people. People who we should study in the round and understand their full contribution both good and bad to our national story. And many of them knew that in their own lifetimes:

“Mr Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint your picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughness, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me.”

When Oliver Cromwell commissioned his portrait from Sir Peter Lely, he was clear that it should bare a true likeness to him and show him for who he was – good and bad.

Many heroes, heroines and villains of history have complex and subjective legacies. A saviour for one will be the oppressor for another and debating and exploring the rights and wrongs of those who are lionised or vilified is key to understanding both our own history and the current composition of our society.

Unfortunately for some this isn’t the case. We seemingly now live in a world where the phrase ‘culture wars’ has, for some, become a proxy for those seeking not to engage in debate but to silence disagreement or dissent. Individuals and self-organised groups have proclaimed themselves the sole arbiters of truth. They decide what the ‘correct’ view is and any attempt to deviate from that singular set of ordained truths is denounced and deplored by those for whom the complex nature of individuals and historic events are just too difficult.

Which brings me back to Lord Horatio Nelson. When a freedom of information request to the National Maritime Museum discovered that the curators of their exhibitions had discussed reflecting the contemporary issues raised by the Black Lives Matter movement in their exhibits, the world exploded. One MP decried in response: “We are fighting this left-wing ideological nonsense every single day in this country.”

And the newly formed “Common Sense Group” of MPs took to their social media to denounce any deviation from the national narrative as an affront to all things British. Their intent was clear: to prevent a museum from publishing or promoting something that they didn’t agree with. This is a form of censorship and it wasn’t even based on fact.

Beyond the anger, the truth about this exhibition was a very different story. You only had to spend three minutes listening to Paddy Rogers, the director of the Royal Museums Greenwich to realise, as he said, that this was a “storm in a tea clipper”. Nelson remains a much-loved figure at the museum and the main exhibits will do nothing to undermine that, rather they will use his persona as a mechanism to explore our current identity and British values.

But the reality isn’t the key aspect here; Nelson’s legacy isn’t the issue, but rather the concept of “culture war” is, with some people trying to build a narrative which sows division and instills a chilling effect on our public space. History is not set in stone. After all, many people’s stories are never told and our perceptions rightly change as we discover more about people’s journeys. Museums and libraries are temples of education and learning. They should be homes for debate and exploration, free from political interference and able to examine every aspect of history and culture without reprisal.

This is especially the case when you consider how some repressive regimes are using their ‘soft’ power to try and launch a real culture war in Europe – using their money and influence to try and re-write history.

In Nantes, France, the Chinese government has intervened to stop an exhibition on Genghis Khan and the Mongols – an issue we’ll be covering more in the weeks ahead. But if we allow one group of people to dictate what should happen in museums, we open the floodgates to all kinds of interested parties to do the same and that is not a path we want to go down.

Here in Britain, we thankfully live in a free society. People are entitled to not go to an exhibition if they think it will offend them, or they can take to social media to write negative reviews of it, but they aren’t allowed to ban it because they don’t agree with the facts presented to them.

Thankfully that isn’t acceptable in a free and tolerant society.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114944″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”right”][vc_column_text]A 12-year-old girl tackled by police and pinned to the ground, a media tycoon in handcuffs, dozens of activists in court – these have become the familiar images from Hong Kong since the passage of the national security law. But there’s another victim of the amplified censorship and persecution happening in the city – academia. Hong Kong’s classrooms and lecture theatres are increasingly at the receiving end of pressure to conform – or else.

Within days of the new law, Hong Kong’s education bureau ordered schools to review all reading materials in the curriculum.

“If any teaching materials have content which is outdated or involves the four crimes under the law, unless they are being used to positively teach pupils about their national security awareness or sense of safeguarding national security, otherwise if they involve other serious crime or socially and morally unacceptable act, they should be removed,” the Education Bureau said in a statement.

Politically sensitive books, including those written by pro-democracy leader Joshua Wong, and titles related to China’s Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen Square massacre, were removed from library shelves. Textbooks censored out phrases like “separation of powers”. Gone too were illustrations showing anti-government protesters and criticism of the mainland Chinese government.

But the purge hasn’t stopped at reading material. Teachers have been fired. Just hours before the law came into effect, a secondary school visual arts teacher, who is too fearful to reveal his real name and goes by the moniker Vawongsir on Instagram, was laid off. He had received a complaint months earlier about critical artwork he’d done outside of work and yet no firm action had been taken against him. Then the new law was announced and he was fired. At the same time, a middle school music teacher’s contract wasn’t renewed after she failed to prevent students from performing a protest anthem during midterm exams.

“If you look at primary and secondary education it’s really obvious what they’re doing. They’re not hiding it,” said Lokman Tsui, assistant professor at Hong Kong’s School of Journalism and Communication, in an interview with Index. Tsui, who formerly held the position of head of free expression at Google in Asia and the Pacific, focuses his research and teaching on digital rights, security, democracy and human rights in general and in China and Hong Kong.

Tsui says the censorship is less obvious in higher education. Less obvious though does not mean less controlling. “They won’t tell you to not do x, y and z but it’s clear it’s not rewarded,” said Tsui.

Tsui himself is an example. Earlier this year he lost his tenure which, as he described in a letter he wrote at the time, “is important for academic freedom, because it provides job security, so you will not be afraid to lose your job if you take on controversial or challenging research topics.” Tsui was unsure whether this was politically motivated, but it cannot be ruled out.

“Maybe it is true that I would have gotten tenure if I had spent my time exclusively and only on ‘safe’ research and nothing else. But that would not have been me,” he wrote in the letter, which received a plethora of responses in solidarity with him and what he had done and in support of his teaching.

Even tenure doesn’t fully protect you in Hong Kong today. Benny Tai, who was associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong and one of the Umbrella Movement leaders, was fired in July. Shui-ka Chun, another university educator known for his political activism, was laid off. China’s liaison office in Hong Kong hailed the terminations as a “purification of the teaching environment.”

Unsurprisingly the result is an atmosphere of self-censorship and an environment in which “the good people leave”.

“It’s a storm and no one wants to go outside, even with an umbrella,” said Tsui.

A battle over independence is nothing new for Hong Kong’s educators. Earlier attempts to introduce a patriotic “national education” curriculum into Hong Kong schools resulted in tens of thousands protesting in 2012, forcing it to be shelved. In 2018, charges of “brainwashing” were once again levelled at the government and at Beijing after attempts were made to alter the way history was taught (more focus on mainland China; less on Hong Kong’s colonial past).

To ensure that teachers fall in line, organisations have been established to report on those who might say the wrong thing. A complaint to the Education Bureau was what led to the aforementioned visual arts teacher Vawongsir being flagged and later fired.

Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing chief executive, has made it quite clear that she isn’t going to go easy on education. The city’s schools and universities are often accused of radicalising Hong Kong’s young with Western ideals and preventing a Chinese national identity from flourishing, accusations reinforced by Lam publicly. At an education forum in 2017 she highlighted that many people arrested for participating in illegal protests over the last year were students.

With each attack usually comes defence, often fierce and determined. And rightly so: minds are shaped in the classroom. But fears are this defence, already strained, will not continue.

As Tsui says, the lines have become further blurred since the passage of the national security law. He describes the law as a “clarion call for the entire society to encourage and amplify everything on the pro-government side” and an “open field-day for harassing anyone” who speaks in favour of the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement.

“I think you have freedom even in China, it’s just the price you want to pay for it and they’ve been raising the price of it. It’s going up and up and up.”

“Realistically it will be difficult for me to find a professorship in Hong Kong,” he said, explaining that there are few universities as is and those that do exist are under pressure to follow the party line.

“While I was trying to get tenure, a lot people told me to keep my head low in order to get it. But I disagreed.”

The costs aren’t just professional.

“There are all kinds of social costs. My mother has said ‘Can you please not be so outspoken?’ Even your friends and your romantic partner will say that.”

Tsui is originally from the Netherlands. Will he be one of the good people forced to leave?

“I’m not leaving until they kick me out. We need people here.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114787″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]One of the things I love about working at Index is the fact that free speech isn’t easy. That every time a new, or even a more established, issue arises you have to think through what it means and how it fits into your own value system.

Should you defend the right of a racist to hide behind their right to free speech? Where is the line between protecting free speech and opposing hate speech?

Free speech underpins our right to protest. However, does that mean if people decide to protest against our free press, that it is legitimate free expression too?

Crucially, if a repressive regime is undermining the right to free speech and attacking every other human right, is a boycott, whether of goods or culture, a legitimate way to protest?

If you believe in the basic human right of free expression – can you and should you boycott? Is your right to protest through boycott or blockades legitimate if the people or items you are boycotting are also simply exercising their right to free speech?

This question has been playing on the team at Index this week.

Every day we discuss what’s happening in China, from the acts of genocide against the Uighur Muslims, to the impact of the national security law in Hong Kong and the latest revelations about the curtailing of human rights in Inner Mongolia.

Every day we despair at what is happening to people who are living under a tyrannical regime that cares little for its citizens and even less for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Which brings me, bizarrely, to the latest Disney film release – Mulan.

Mulan should be an inspirational story, one of a woman whose actions saved a dynasty.

A woman who didn’t want her father to face another conscription, to fight in a war she knew would lead to his death. To protect her family, she pretended to be a man and joined the army and ultimately saved the day.

However, the latest version of the story is rightly proving to be controversial.

The actor playing Mulan has praised the actions of the police against the protestors in Hong Kong – parroting the Chinese Communist Party line straight from Beijing.

The script of the film shows Mulan as Han Chinese and not of Mongolian origin as many believe she was. The views of one actor, as wrong as I believe them to be, are a matter for her. The cultural misrepresentation makes for an inaccurate and to many an offensive film, but these editorial choices do not warrant a boycott of someone’s art.

What might is that Disney shot the film in the Xinjiang province.

Xinjiang is the home of the majority Muslim Uighur community and, now, the site of numerous concentration camps, where women are being forcibly sterilised, piles of human hair are being collected, people are being disappeared and the term re-education has become code for the eradication of any cultural identity that does not subscribe to the Beijing norm.

The term for this is genocide. A mass killing and cultural subjugation waged against millions of people. And it is happening today, right now in Xinjiang on the orders of the Chinese Communist Party.

Disney chose to film their latest Mulan adaptation in Xinjiang and, in doing so, have marginalised the suffering of our fellow human beings. Disney exists to turn fantasies and fairy tales into real life, their raison d’etre is to transport us all to worlds of innocent pleasure. Yet they used their power to thank the public security bureau in the city of Turpan and the “publicity department of CPC Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomy Region Committee” in the end credits.

They thanked the people who are not only complicit but who are seemingly orchestrating acts of genocide. Their power and agency was used not to stand with the oppressed but with the oppressors.

Index doesn’t support boycotts; we were established to publish the work of censored artists and writers – those who are being persecuted. In my opinion that puts us on the side of the Uighurs not Disney.

Disney isn’t persecuted, it isn’t being censored – you can still see Mulan. But choices and actions have consequences. The choices Disney made to ignore the inconvenient truth of a genocide are not immune from scrutiny because their end product is an artistic output. This is a company that should be held accountable for its actions.

Free speech is important; it’s vital. It gives every one of us the right to protest. So, I’m using my right of free speech to say that I think Disney should be ashamed and that I won’t be watching Mulan and I don’t think anyone else should either. I stand with the Uighurs.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also want to read” category_id=”13527″][/vc_column][/vc_row]