Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

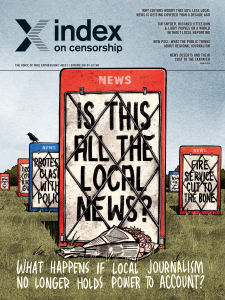

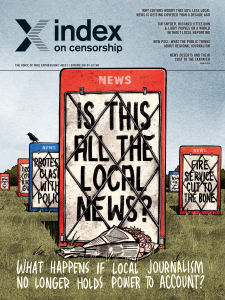

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

FEATURING

Writer

Novelist

Author

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Worrying about a local newspaper closing or reporters being centralised is not just nostalgia, it’s being concerned that our democratic watchdogs are going missing, says Rachael Jolley in the spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Is this all the local news? The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the local news?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F03%2Fmagazine-is-this-all-the-local-news%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine asks Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?

With: Libby Purves, Julie Posetti and Mark Frary[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/03/magazine-is-this-all-the-local-news/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104228″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine, Sally Gimson, deputy editor, and Tracey Bagshaw, journalist and magazine contributor — with special help from editorial assistant Lewis Jennings — were live on air at Resonance FM on 21 January to discuss the latest issue which takes a special look at why different societies stop people discussing the most significant events in life.

In China, as Karoline Kan reports, women were forced for many years to have just one child and now they are being pushed to have two, but it is not something to talk about. In South Korea Steven Borowiec finds men have taken to social media to condemn a new film adaptation of a novel about motherhood. Irene Caselli describes the consequences in Latin America of preventing discussion about contraception and sexually transmitted infections. Joan McFadden digs into attitudes to gay marriage in the Hebrides, where she grew up, and interviews the Presbyterian minister who demonstrated against Lewis Pride. We have an original play from Syrian dramatist Liwaa Yazji about fear and violent death. While flash fiction writer Neema Komba imagines a Tanzanian bride challenging the marriage committee over her wedding cake. Finally, Nobel-prize-winning author Svetlana Alexievich tells us that she is sanguine about the mortal dangers of chronicling and criticising post-Soviet Russia.

Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpetine Gallery and MagCulture (all London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool). Red Lion Books (Colchester) and Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The Winter 2018 podcast can also be found on iTunes.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1548431570319-1f2dca2e-e6db-5″ taxonomies=”30752″][/vc_column][/vc_row]