Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

|

|

Mada Masr is an Egyptian online news site formed just before the military coup in July 2013 by 24 friends and journalists. Published in both English and Arabic, the site aims to offer an alternative to newspapers censored by state-owned printing and distribution facilities and media owned by industrial conglomerates. Wanting to represent in practice what Egypt was trying to achieve, Mada aims to be entirely democratic and is owned and run by its original founders and the journalists who write for it.

Editor-in-chief, Lina Attalah is well-known Egyptian media figure and former editor of Egypt Independent, which was shut down in April 2013 by the management of Al-Masry Media Corporation. When the editorial team tried to release a final edition explaining why, it was also pulled just before going to print. Attalah published it anyway, with the promise that “In keeping with our practice of critical journalism, we use our final issue to reflect on the political and economic challenges facing Egyptian media, including in our own institution.” Many of the founders of Mada Masr are former employees of Egypt Independent.

Since its formation, Mada Masr has seen Egypt go through the popular uprising against Islamist President Mohammed Morsi, the military’s overthrow of Morsi and the subsequent violent crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood protesters, and the spread of terrorist violence in the country. Mada’s reporters work in a country with 186 laws restricting freedom of the press and expression.

In November 2015, Mada journalist Hossam Bahgat was summoned by Egypt’s military intelligence detained for two days, after he wrote a story about the prosecution of about two dozen military officers for allegedly plotting a coup. The arrest was condemned globally, and Bahgat was eventually released, after which Mada published his statement describing the detention.

With many investors are politically aligned with the military regime, and those that weren’t facing huge pressure, funding has been a problem for Mada Masr. Valuing its independence above all else, Mada has come up with some innovative fundraising ideas, including, a pop-up marketplace launched in April which sells designer clothes and urban crafts.

One of Mada’s new editorial initiatives is to create networks of citizen journalists to bring in more local reporting — and readers — throughout Egypt’s governorates.

“We have established a cooperative media organisation independently, at a time when media are controlled and only made possible through either the state or wealthy businessmen,” said Lina Attalah. “We are experiencing some deal of fear while doing our jobs every day.”

But Mada Masr has not allowed this to guide them towards self-censorship, she says. “With our minds and hearts grappling with being progressive and practical, we build our institution with an ambition to respond to that which we critique in our coverage.”

“I want us, down the line, many, many years to come, to be a reference of what happened.”

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

The arrest by Turkey of journalists for Vice News, just two days after the sentencing of Al Jazeera reporters in Egypt, demonstrates how easily terror laws can be abused to stifle a free and independent media.

It should be a wake-up call for the UK, which in the next few months will introduce yet another piece of anti-terrorism and extremism legislation that could be used in much the same way.

On Monday, two British reporters and a translator working for international news organisation Vice News were charged by a Turkish court for “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”, after filming clashes between government forces and Kurdish militants. The charges came just days after the sentencing in Egypt of three Al Jazeera journalists – accused of aiding the banned Muslim Brotherhood – for “spreading false news”.

The injustice in both cases is patent. In both cases laws meant to tackle terrorism and extremism are being used against journalists simply trying to do their job: to report the news.

Tobias Ellwood, the UK Minister for the Middle East and North Africa, said he was, “deeply concerned by the sentences handed down” against the journalists in Egypt. But what should also be concerning us is how easily that could happen in the UK as the government seeks ever broader powers, and definitions of terrorism that uses language little different to that being used to charge journalists like those of Vice News and Al Jazeera.

The UK government already defines extremism very broadly, as “the vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs” – a net wide enough to catch Islamic fundamentalists, neo-Nazis, but also potentially anyone who preaches, for example, against gay marriage. But the government is not content. Now it says it needs new laws to tackle those who “spread hate but who do not break existing laws”. And that is a net wide enough to catch, well, pretty much anyone who says anything with which the current government – or mainstream popular opinion – disagrees.

Conservative MP Mark Spencer argued last month that proposed new banning orders intended to clamp down on hate preachers and terrorist propagandists should be used against Christian teachers who teach children that “gay marriage is wrong”. And if that could be the case, it takes little imagination to see that “spreading hate” could easily be applied to those journalists who report on those groups and individuals who have hateful messages.

The government will argue that this is not how the law is intended. But you only have to look at communications intercept laws to see how easily “intentions” can be subverted and abused in practice. Police officers used powers afforded by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) – an act intended to deal with terrorists – to pull the phone records of Sun political editor Tom Newton Dunn so it could track down the officers accused of leaking information to the Sun over “Plebgate” – an incident with no terrorist implications whatsoever in which a minister was accused at swearing at the police.

The new extremism bill will be no different. It will give the government powers to ban a host of groups from speaking or publishing, powers that can easily be used to silence those not just with whom the government disagrees, but those on whom we rely to convey information – even when that information, as is so often the case with those brave enough to report on the most violent extremism, is deeply unpalatable.

Britain has rightly described itself as shocked by the Al Jazeera verdict in Egypt. I hope it will be vocal in its condemnation of the arrest of VICE News’ journalists in Turkey. And I hope it will then reconsider its plans to introduce new terror laws that will stifle free expression and a free media.

This article was originally posted at Open Democracy on 1 September 2015

The anti-terror charges against reporters for Vice News in Turkey are not isolated. In recent years, a number of countries have used broad anti-terror laws to restrict the freedom of the press.

Turkey

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

Two British journalists and a local fixer working for Vice News were charged on Monday 31 August in Turkey with “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”. They will remain in detention until their trial, the date of which has not yet been announced.

The journalists Jake Hanrahan, Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between security forces and youth members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir on Thursday when they were arrested.

Turkey’s broad definition of terrorism means that any journalist reporting on PKK activities or Kurdish rights can be charged with the offence of making “terrorist propaganda” and jailed.

Index on Censorship Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg said: “Coming just days after the unjust sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, these latest detentions of journalists simply for doing their jobs underlines the way in which governments everywhere can use terror legislation to prevent the media from operating.”

Egypt

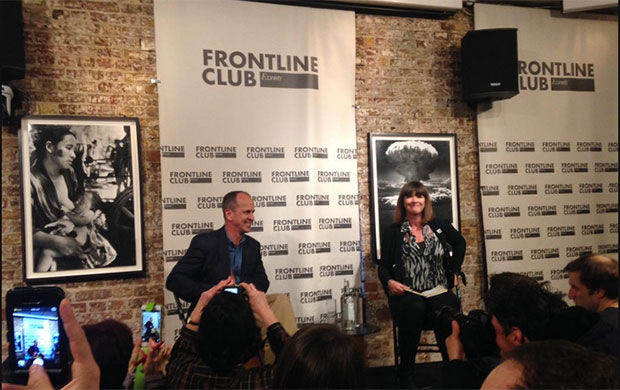

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Egypt remains a cause for concern when it comes to press freedom: on 29 August 2015 Al Jazeera journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were sentenced to three years in prison. The journalists were found guilty of of “broadcasting false information” and “aiding a terrorist organisation” – a reference to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The sentencing came just weeks after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government passed an anti-terror law setting a fine of up to 500,000 Egyptian pounds (£41,600) for journalists who stray from government statements or spread “false” reports on attacks or security operations against armed fighters.

Jordan

Abdullah II of Jordan at a conference in Amman in 2013. Ahmad A Atwah / Shutterstock.com

Jordan introduced a new “anti-terror” law in 2006 prohibiting, among other things, the engagement in “acts that expose the kingdom to risk of hostile acts, disturb its relations with a foreign state, or expose Jordanians to acts of retaliation against them or their money”. The charge carries a prison sentence of three to 20 years. The law was amended in 2014 to , broaden the definition of terrorism.

Interpretation of the law has been varied. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in April 2015 a journalist was jailed for criticising the Saudi-led bombing of Houthi forces in Yemen. Another journalist was detained in July 2015 for breaking a recent ban on coverage of a terror plot. Earlier in 2015, an activist who criticised the royal family’s support of Charlie Hebdo on Facebook was sentenced to five months in jail under the anti-terror law.

Tunisia

One month after June’s terrorist attack on Sousse beach killing 38 tourists, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, Tunisia approved new anti-terror legislation.

Under the legislation, website editor Nour Edine Mbarki was charged in connection with publishing a photograph of a car that purportedly transported a gunman behind the beach attack. According to the CPJ, he was charged under Article 18 of the law with “complicity in a terrorist attack and facilitating the escape of terrorists,” which carries a prison term of between five and 12 years. He is currently awaiting a trial date.

Human Rights Watch said the new anti-terror bill “would open the way to prosecuting political dissent as terrorism, give judges overly broad powers, and curtail lawyers’ ability to provide an effective defence”.

Pakistan

Rights groups have long criticised Pakistan’s notorious anti-blasphemy laws for their effect on freedom of expression in the country. But strengthened anti terror legislation is also impacting the way journalists operate in the country.

In June, three Pakistani journalists were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act, reportedly for covering the activities of a dissident politician, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation. A year before, a TV anchor was also charged under the law.

One to watch: Kenya

Following two separate attacks by al-Shabab militants in December, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law a new security bill that could curtail press freedom. Under the new law, journalists could face up to three years in jail if their reports “undermine investigations or security operations relating to terrorism” – or even if they published images of “terror victims” without police permission.

This hasn’t come into play yet – in February, the Kenyan High Court threw out several clauses, including those that could impact media freedom. The government has said it would consider lodging an appeal.

This post was written by Emily Wight for Index on Censorship

This article was posted on 1 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Photo – Ramy Essam, Tahrir Square – Festival 800

Join us in Lincoln for Festival 800, a celebration of the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta – a unique and powerful statement that began the world’s march to freedom and liberty.

Index on Censorship are delighted to be supporting Festival 800 and Freemuse who are staging a special day focused on musicians who have been banned from performing their work in their own countries. Events include:

13:30 – Listen to the Banned

Listen to the Banned is a compilation album that features the music of banned, censored and imprisoned artists from the Middle East, Africa and Asia. Project co-founders, music producer Deeyah Khan and Ole Reitov, executive director of Freemuse discuss the album’s origins and their wider work. Khan is a critically acclaimed composer, award-winning documentary film director and celebrated human rights activist. (£8)

16:00 – Talking With the Banned

Two international musicians who have faced censorship, “exiled bard of the Egyptian revolution” Ramy Essam and Basque artist Fermin Muguruza, join others including Deeyah Khan, editor of Index on Censorship magazine Rachael Jolley, and author and academic Martin Cloonan (chair) for a conversation about censorship. (£5)

19:30 – The Banned – Live and unplugged in concert.

A live gig featuring folk musician Ramy Essam who was catapulted to fame by the events of Tahrir Square; Lavon Volski, an icon of Belarusian rock music and Fermin Muguruza, who sings against the oppression that he feels Spain has over Basque Country. With Attila the Stockbroker as MC. (£10)

When: Saturday 5 September 2015, timings as above.

Where: Lincoln Performing Arts Centre, LN6 7TS (map)

Tickets: Special Index offer for whole day £15, quote INDEX when booking.