Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

With much anticipation, Egyptians huddled around their television sets on Friday night to watch their favourite comedian, Bassem Youssef, make his debut appearance on the Saudi-funded MBC Misr Channel after a three-month absence from the small screen.

Youssef’s fans were not disappointed: They were treated to a full hour of non-stop laughter as the satirist, often compared to US comedian John Stewart, took jibes at the current state of the media and at the Egyptian public’s infatuation with defence minister field marshall Abdel Fattah El Sisi. Youssef cracked jokes about how everything in the country revolves around El Sisi whose name crops up on practically every TV show including cookery and sports programmes.

Youssef opened the show with a pledge not to talk about “sensitive political issues” that had previously caused his satirical show Al Bernameg, The Programme, to be pulled off the air by the management of the privately-owned Egyptian CBC satellite channel. Minutes later, he reversed his decision. “What are we going to talk about?” he asked his studio audience before throwing caution to the wind and starting to poke fun at the Sisi-mania gripping the country. He stopped short however, of taking aim at El Sisi himself, making no secret of the fact that such action would provoke a negative response from the censors.

” It’s better we don’t mention him,” he said as a silhouette- image of the military chief appeared on the screen . “Not out of fear but out of respect,” he sarcastically retorted.

Youssef’s show Al Bernameg was suspended last October following a controversial episode that CBC administrators said had “violated editorial policies and caused discontent among viewers.” In that episode–his first appearance since Islamist president Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests in July– Youssef had poked fun at the Egyptian public’s blind idolisation of General El Sisi, widely expected to become the country’s next president. That had been enough to land him in trouble.

Not only was the show pulled off the air, but Youssef was also lambasted mercilessly by pro-military supporters in both the traditional media and social media. The attacks on Youssef did not stop there: Criminal charges were brought against him by angry citizens who accused him of “insulting the military.”

The legal complaints lodged against Youssef in November were not the first time the popular satirist had been indicted. In March 2013, he was investigated by the public prosecutor on a set of charges ranging from “insulting Pakistan” to “spreading atheism” and “insulting Islam and the president.” The accusations against him were triggered by his persistent ridiculing of then-president Mohamed Morsi. In an episode of the show early last year, he appeared on the set wearing a gigantic hat similar to one worn by Morsi when he received an honorary doctorate from a Pakistani university. Youssef’s unabashed lampooning of the former president delighted the former president’s opponents while earning Youssef the wrath of his Islamist supporters.

Youssef was not convicted. After an investigation lasting five-hours, he was released on $2,200 bail and went right back to mocking Morsi.

His indictment triggered an international outcry, raising concerns over regression on the country’s hard won freedom of expression and press freedom. Little did anyone –let alone Youssef himself who later joined the June 30 protests demanding the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime—suspect at the time that those freedoms would be further undermined and eroded by the military-backed regime that would replace Morsi three months later.

Since Morsi’s ouster, restrictions on the press have been even “greater than those imposed by either Morsi or his predecessor, autocrat Hosni Mubarak”, lament press freedom advocates and media analysts. The intimidation and harassment of journalists including increased physical assaults on them by security forces and by ordinary Egyptians supportive of the military, have raised concerns about the safety of journalists working in Egypt and press freedom in the country.

The indictment of 20 journalists – four of them foreign correspondents—has fuelled fears of a widening crackdown on journalists critical of the military-backed government. Eight of the defendants are journalists working with the Al Jazeera network –four of whom languish in prison on charges of “spreading false news and assisting or belonging to a terrorist organization.” Similar charges have been leveled against the sixteen other defendants in the case including Dutch journalist Rena Nejtes who last week, managed to flee the country, escaping arrest.

Sue Turton, one of two British defendants in what has come to be known as the “Al Jazeera case” told CNN on Friday that “the crackdown by the Egyptian authorities was targeting all journalists who do not tow the government line. ” She and fellow British defendant Dominic Kane are safely out of the country unlike Australian award-winning journalist Peter Greste who has been behind bars for six weeks. On Sunday, his parents made an impassioned appeal to Egyptian authorities for his release. Speaking to journalists in a press conference in Cairo, they described the accusations against him as “bizarre” and “ludicrous.” Juris Greste , Peter’s father, insisted his son’s detention was ” unfair and unjustifiable,” and urged prosecutors to release him immediately.

In a worldwide campaign to press for the release of the four Al Jazeera journalists, fellow-journalists from different countries across the globe have expressed solidarity with the defendants. They posted their own pictures on social media networks—with their mouths plastered ” to symbolize the Egyptian regime’s gagging of the press,” one campaigner explained via her Twitter account.

The detention of the Al Jazeera journalists is having a chilling effect on journalists working in Egypt, forcing many local journalists to practice self- censorship for fear of potential government reprisals. Others have fallen silent.

In the current hostile environment , it is not surprising that Youssef too is uncertain if he will be allowed to continue broadcasting his show. Wrapping up Friday’s episode, he asked “Second episode ?” before bursting out laughing. In the country’s repressive climate, no one can predict what might happen next.

This article was posted on 10 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Just as rights groups and press freedom advocates were thinking things could not get any worse for journalists in Egypt, a video that aired on an Egyptian private TV channel showing the arrest of Al Jazeera journalists Peter Greste and Mohamed Fahmy, proved them wrong.

The footage shown on the channel “Tahrir” on Sunday night was far less dramatic than the background music to which it was set –the kind of ominous-sounding soundtrack used to create suspense in intense mystery movies. It featured lingering shots of recording equipment including cameras, microphones, electronic cables, laptop computers and mobile phones used by the journalists in their work prior to their arrest. It also showed a perplexed-looking Fahmy being interrogated during the raid on his Cairo hotel room . Meanwhile, a caption at the bottom of the screen read ” exclusive footage of the Marriot cell accused of fabricating news on Al Jazeera.”

The interrogator who did not appear in the video but could only be heard, asked Fahmy about the type of work they were doing , why they were working out of a hotel room and how they get paid by the network. Asked if he had valid press credentials, Fahmy replied that his accreditation card had expired sometime ago. He added that he had applied for new credentials and was waiting to hear back from authorities.

The airing of the video drew fierce condemnation from Al Jazeera –the Qatari-funded network targeted by Egyptian authorities who accuse it of “inciting violence” and of being ” a mouthpiece for the Muslim Brotherhood”. In the first-of-its-kind prosecution in Egypt, 20 Al Jazeera journalists have been charged with conspiring with terrorists and manipulating clips that tarnish Egypt’s image abroad by protraying the country as being on the brink of civil war. Al Jazeera has denied the allegations, insisting its journalists were only doing their job. Fahmy, Greste and producer Baher Mohamed , who are among the defendants in what has come to be known as the Al Jazeera case, had been in custody for five weeks before formal charges were brought against them on Saturday. Two cameramen working for the Al Jazeera Arabic service and Al Jazeera Mubasher are also behind bars . They were arrested last summer while covering the unrest that erupted after the country’s first democratically elected President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests. One of the two defendants– Cameraman Mohamed Badr– was acquitted earlier this week along with sixty one suspect-protesters after spending the last six months in jail.

In a statement published on its website, Al Jazeera said Sunday’s airing of the controversial video was “another attempt to demonise its journalists”, adding that “it could prejudice the trial.”

Rights groups meanwhile see the detention of the Al Jazeera journalists as part of a wider crackdown on freedom of expression in the country. Index on Censorship — along with partner organisations Article 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reports Without Borders– condemned the Egyptian government’s attacks on media freedom and called for the release of the journalists. (Full statement: English | Arabic)

“What has happened with the Al Jazeera journalists is part of an overall attempt to repress freedom of expression,” said Salil Shetty, Secretary General of Amnesty International. In an interview with Al Jazeera, he urged the international community to keep up pressure on the Egyptian government to resolve the situation.

Egyptian and foreign journalists also joined the chorus of denunciations of the aired video, using social media networks to express their alarm and frustration.

“The video and detention of Fahmy and Greste make our jobs as journalists in Egypt all the more difficult, ” Egyptian Journalist Nadine Maroushi complained on Twitter. Some reiterated calls for Twitter-users to follow the “FreeFahmy” hashtag on Twitter in support of the Al Jazeera detainees. Others dismissed the video as “ridiculous,” joking about how the items found in the room –such as a copy of Lonely Planet Egypt (which presumably belongs to Greste)–were “the evidence that would likely incriminate the journalists. ”

“The cameras, laptops and flipped toilet seat are proof that the journalists’hotel room was a den of espionage,”was another tongue-in-cheek comment posted on the social media network. Using Fahmy’s Twitter account, his brother Sherif sent a bitter message on Monday saying ” In Egypt, you are guilty until proven innocent.”

Meanwhile , foreign journalists’ associations are planning protest marches on Tuesday outside Egyptian embassies in cities as far away as Nairobi to demand the release of the detained journalists. Egypt’s military-backed government has so far largely ignored the calls , turning a blind eye to a petition signed last month by journalists and editors from more than fifty- two news organizations . Media freedom advocates are hoping however ,that Cameraman Mohamed Badr’s acquittal may be a sign that the government was finally easing its heavy-handed crackdown on journalists. They also hope that the Egyptian authorities would keep their recently- made promise of “ensuring that foreign journalists work freely to cover the news in an objective and balanced manner.” The pledge was made in a statement released on January 30 by the State Information Service–the government body responsible for accrediting foreign journalists.

They say the onus is now on the government to show its commitment to implementing articles in the constitution guaranteeing freedom of expression and the press. Releasing Fahmy and the other detained Al Jazeera journalists would be a step in the right direction.

This article was posted on 4 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

Statement: Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom from Article 19, the Committee to Project Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders. PDF: Arabic

The wording of proposed anti-terrorism legislation in Egypt has been leaked, sparking concern amongst opposition activists over upcoming government censorship. The legislation could allow for social networking sites such as Facebook to be barred, if they are deemed to be endangering public order.

Al Sherooq, an Arabic-language daily newspaper, reported on the news, stating that ant-terrorism legislation “for the first time includes new laws which guarantee control over ‘terrorism’ crimes in a comprehensive manner, starting with the monitoring of Facebook and the Internet, in order of them not to be used for terrorism purposes”.

According to Al Sherooq, the document is now being circulated around Cabinet for approval, and will build upon the country’s new constitution, recently approved with 98% support. The constitution includes provisions for emergency legislation at points of crisis.

The law is ostensibly designed to improve the ability of the military government to provide security, against a backdrop of rising violence and terrorism attacks. It lays out proposed punishments for those involved with designated terrorism offences, and for inciting violence. It would also establish a special prosecution unit and criminal court focused on convicting terrorists.

The leaked document also shows how broadly terrorism will be defined, as it includes “use of threat, violence, or intimidation to breach public order, to violate security, to endanger people”. It is also defined “as acts of violence, threat, intimidation that obstruct public authorities or government, as well as implementation of the constitution”.

Commentators were quick to note that Facebook would be high on the list of potentially barred sites, as it is frequently used by members of the Muslim Brotherhood and other opposition groups, to co-ordinate protests.

YouTube has also recently been used by jihadist groups; one video posted recently showed a masked man firing a rocket at a freight ship passing through the Suez.

“What worries me most is the level of popular support for these laws,” said Mai El-Sadany, an Egyptian-American rights activist. “If you look at how much support the referendum won, and also recent polling about the terrorism laws, there is definitely a sense that people want peace and stability.”

“But Egypt now is like America after 9/11,” she added. “People are believing the lies the government are telling them. There is the same sentiment of fear, with a legitimate basis, but human rights abuses and loss of civil liberty are a possibility.”

Since Morsi’s deposal in July 2013, terrorists group have attempteed to kill the interior minister, bombed the National Security heaquarters in Mansoura and Cairo, shot down a military helicopter in the Sinai Peninsula, fired a rocket at a passing freighter ship in the Suez canal, and assassinated a senior security official. A group calling itself Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (translated as “Supporter of Jerusalem”) has claimed responsibility for most of the attacks.

The constitutional referendum result has already been used by the regime to demonstrate Sisi’s credibility. However, critics say that any media channels supportive of the opposing Islamist agenda were all shut down after the military coup, and that voters suggesting they might vote against the referendum were threatened by government officials, suggesting Sisi’s mandate may be questionable.

There was also a notable lack of support for the referendum in the south of Egypt as opposed to the north.

Recent polling data suggests that the terrorism legislation could be popular, with 65% of Egyptians having heard about possible new laws, and 62% approving of it. Polling results also showed significantly more support amongst degree-educated Egyptians as opposed to less educated people.

An earlier form of the legislation has already been used to arrest dozens of activists and journalists, including several employees of Al Jazeera. Viewership of the Qatar-based network has reduced as support for the Muslim Brotherhood has declined. The Muslim Brotherhood’s activities in Egypt have been funded by Gulf states.

It is thought the new definition of terrorism could be used to indict the detained Al Jazeera journalists. To date, it has been unclear under what legislation they could be prosecuted.

Political analyst and blogger Ramy Yaccoub, from Cairo, criticised the leaked legislation voraciously via his Twitter account: “This is becoming ridiculous,” he tweeted. This was followed by: “There needs to be an international treaty that governs the sanctity of private communication.”

There is currently no agreed timeframe for the Egyptian legislative process, so it is unclear how long it will take for the laws to come into force.

The wording of the legislation has been translated into English and is available here.

This article was posted on 3 Feb 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

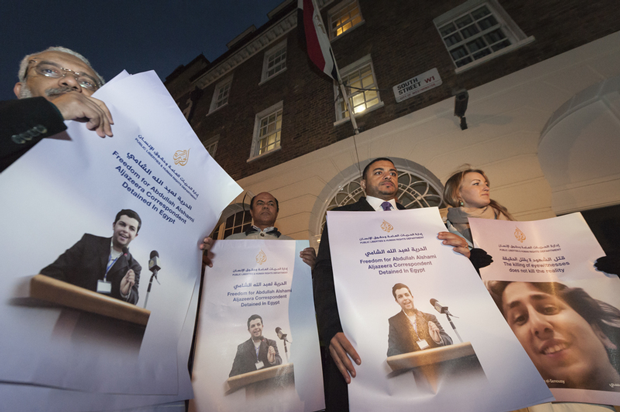

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

Statement: Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom from Article 19, the Committee to Project Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders

Twenty journalists working for the Al Jazeera TV network will stand trial in Egypt on charges of spreading false news that harms national security and assisting or joining a terrorist cell.

Sixteen of the defendants are Egyptian nationals while four are foreigners: a Dutch national, two Britons and Australian Peter Greste, a former BBC Correspondent. The chief prosecutor’s office released a statement on Wednesday saying that several of the defendants were already in custody; the rest will be tried in absentia.The names of the defendants, however, were not revealed. The case marks the first time journalists in Egypt have faced trial on terrorism-related charges, drawing condemnation from rights groups and fueling fears of a worsening crackdown on press freedom in Egypt .

“This is an insult to the law,” said Gamal Eid, a rights lawyer and head of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information. “If there is justice in Egypt , courts would not be used to settle political scores”, he added.

In December, the government designated the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. It has since widened its heavy-handed crackdown on Brotherhood supporters, targeting pro-democracy activists, journalists and anyone considered remotely sympathetic to the outlawed Islamist group.

In a move seen by rights advocates as a blow to freedom of expression, most Islamist channels were shut down by the Egyptian authorities almost immediately after Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was toppled in July. The Qatar-based Al-Jazeera is one of the few remaining networks perceived by the authorities as sympathetic to Morsi and the Brotherhood.

Once praised by Egyptians as the “voice of the people” for its coverage before and during the 2011 mass protests that led to the removal of autocrat Hosni Mubarak from power, Al Jazeera has since seen its popularity dwindle in Egypt. Since Morsi’s ouster by military-backed protests in July, Qatar has been the target of media and popular wrath because of its backing for the Brotherhood. Allegations by the state controlled and private pro-government media that Qatar was”plotting to undermine Egypt’s stability” has inflamed public anger against the Qatar-funded network, prompting physical and verbal attacks by Egyptians on the streets on journalists suspected of working for Al Jazeera.

The Al Jazeera Arabic service and its Egyptian affiliate Mubasher Misr were the initial targets of a government crackdown on the network and have had their offices ransacked by security forces a number of times. In recent months however, the crackdown on the network has escalated, targeting journalists working for the Al Jazeera English service as well despite a general perception among Egyptians that the latter is “more balanced and fair” in its coverage of the political crisis in Egypt.

The Al Jazeera network has denied any biases on its part and has repeatedly called on Egypt to release its detained staff. According to a statement released by Al Jazeera on Wednesday, the allegations made by Egypt’s chief prosecutor against its journalists are “absurd, baseless and false.”

“This is a challenge to free speech, to the right of journalists to report on all aspects of events, and to the right of people to know what is going on.” the statement said.

Three members of an Al Jazeera English (AJE) TV crew were arrested in a December police raid on their makeshift studio in a Cairo luxury hotel and have remained in custody for a month without charge. Both Canadian-Egyptian journalist Mohamed Fahmy — the channel’s bureau chief –and producer Baher Mohamed have been kept in solitary confinement in the Scorpion high security prison reserved for suspected terrorists and dangerous criminals. An investigator in the case who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the press said Fahmy was an alleged member of a terror group and had been fabricating news to tarnish Egypt’s image abroad.

Earlier this week, Fahmy’s brother, Sherif, complained that treatment of his brother had taken a turn for the worse and that prison guards had taken away his watch, blanket and writing materials.

Peter Greste, the only non-Egyptian member of the AJE team has meanwhile, been held at Torah Prison in slightly better conditions. In a letter smuggled out of his prison cell earlier this month, Greste recounted the ordeal of his Egyptian detained colleagues, saying “Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both men spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul-destroying tedium.”

Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah El Shamy, another defendant in the case, has meanwhile been in jail for 22 weeks. He was arrested on August 14 while covering the forced dispersal by security forces of a pro-Morsi sit-in and has been charged with inciting violence, assaulting police officers and disturbing public order. El Shamy began a hunger strike ten days ago to protest his continued detention. In a letter leaked from his cell at Torah Prison and posted on Facebook by his brother, El Shamy insisted he was innocent of all charges. He remains defiant however, saying that “nothing will break my will or dignity.” On Thursday, his detention was extended for 45 days pending further investigations . His brother Mohamed El Shamy, a photojournalist, was arrested in Cairo on Tuesday while taking photos at a pro-Muslim Brotherhood protest. He was released a few hours later.

Al Jazeera Mubashir cameraman Mohamed Badr is also behind bars. He was arrested while covering clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and security forces in July and has remained in custody since.

The case of the Al Jazeera journalists sends a chilling message to journalists that there is a high price to pay for giving the Muslim Brotherhood a voice. A journalist working for a private pro-government Arabic daily sarcastly told Index that there is only one side to the story in Egypt: the government line. Mosa’ab El Shamy, a photojournalist whose brother is one of the defendants in the Al Jazeera case posted an article this week on the website Buzzfeed, humorously titled: If you want to get arrested in Egypt, work as a journalist.

In truth though, the case is no laughing matter. National Public Radio’s Cairo Correspondent Leila Fadel said it shows just how far Egypt has backslid on the goals of the January 2011 uprising when pro-democracy protesters had demanded greater freedom of expression. Today, violations against press freedoms in Egypt are the worst in decades, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. Sadly, it does not look like the situation for journalists in Egypt will improve anytime soon.

In the meantime the fate of the Al Jazeera journalists hangs in the balance.

This article was posted on 31 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org