Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Wednesday marked International Women’s Day, an opportunity to reflect upon the role of women in society. In the midst of a war in Europe and global economic crisis it is easy to focus on the immediate, on the current existential crisis, but there is an onus on us to remember what is happening further afield.

On Wednesday for International Women’s Day I addressed students on behalf of the Anne Frank Trust. I highlighted the importance of not only telling women’s stories but also the power of amplifying their lived experiences, wherever they may be. Collectively we all made a promise that this week – and I hope in future weeks – we would seek to tell the stories of the women who have made a mark and ensure that the world knows their names.

I seek to deliver on that promise.

I am proud to be the Chief Executive of Index on Censorship, a charity which endeavours to provide a voice to the persecuted, which campaigns for freedom of expression around the world. I work daily with dissidents who risk everything to change their societies and their communities for the better. Men and women. But today I would like to highlight the names of some of those women who have paid the ultimate sacrifice in the last year for the supposed “crime” of doing something we take for granted every day – using the human right of freedom of expression.

Deborah Samuel – a student brutally murdered in Nigeria after being accused of blasphemy on an academic social media platform.

Nokuthula Mabaso – a leading woman human rights defender in South Africa and leader of the eKhenana Commune. She was assassinated outside of her home, in front of her children.

Shireen Abu Akleh – a veteran Palestinian-American correspondent for Al Jazeera who was killed while reporting on an Israeli raid in the West Bank.

Jhannah Villegas – a local journalist in the Philippines was killed at her home. The police believe this was linked to her work.

Francisca Sandoval – a local Chilean journalist was murdered, and several others hurt when gunmen opened fire on a Workers’ Day demonstration.

Mahsa Amini – a name all too familiar to us, as her murder inspired a peaceful revolution which continues to this day. Murdered by the Iranian morality police for “inappropriate attire”.

Oksana Baulina – a Russian journalist killed during shelling by Russian forces in the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

Oksana Haidar – a 54-year-old Ukrainian journalist and blogger better known under the pseudonym “Ruda Pani”, killed by Russian artillery, northeast of Kyiv.

Oleksandra Kuvshynova – a Ukrainian producer who was killed outside of Kyiv, while working with Fox News.

Petronella Baloyi – a South African land and women human rights defender gunned down while in her home.

Yessenia Mollinedo Falconi, a Mexican journalist who was the founder and editor of El Veraz. A crime and security correspondent, she received a death threat a fortnight before she was shot. She was killed alongside her colleague Sheila Johana García Olivera

Vira Hyrych – a journalist for Radio Free Europe’s Ukrainian service, killed by Russian shelling.

Yeimi Chocué Camayo – an Indigenous women’s rights activist, killed in Columbia when returning to her house.

Cielo Rujeles – wife of social leader Sócrates Sevillano, shot and killed alongside her husband in Colombia.

Luz Angelina Quijano Poveda – a delegate of the Community Action Board in Punta Betín, Colombia, murdered at her home.

Sandra Patricia Montenegro – a PE teacher and social leader was shot and killed in front of her students in Colombia.

Melissa Núñez – a transgender activist shot dead by armed men in Honduras.

María del Carmen Vázquez – a Mexican activist and member of the Missing Persons of Pénjamo, murdered by two men at her home in. She was looking for her son who disappeared last summer.

Blanca Esmeralda Gallardo – activist and member of the Collective Voice of the Missing in Puebla, who was assassinated on the side of the highway in Mexico as she waited for a bus to take her to work. She was searching for her 22-year-old daughter who vanished in 2021.

Yermy Chocue Camayo – treasurer of the Chimborazo indigenous reservation in Colombia, and human rights defender, killed as she headed home.

Dilia Contreras – an experienced presenter for RCN Radio in Columbia, shot dead in a car alongside her colleague Leiner Montero after covering a festival in a local village.

Edilsan Andrade – a Colombian social leader and local politician, shot and killed in the presence of one of her children.

Jesusita Moreno, aka Doña Tuta – a human rights activist who defended Afro-Colombian community rights. Facing threats against her life, she was assassinated whilst at her son’s birthday party.

Maria Piedad Aguirre – a Colombian social leader who was a defender of black communities, violently murdered with a machete; she was found at home by one of her grandchildren.

Elizabeth Mendoza – social leader, was shot and killed in her home in Colombia. Her husband, son and nephew were also murdered.

María José Arciniegas Salinas – a Colombian indigenous human rights defender, assassinated by armed men who said they belonged to the Comandos de la Frontera group.

Shaina Vanessa Pretel Gómez – who was known among the LGBTIQ+ community for her activism, including work to establish safe spaces for homeless people and a passion for the arts, was shot dead early in the morning by a suspect on a motorbike.

Rosa Elena Celix Guañarita – a Colombian human rights defender was shot while socialising with friends.

Mariela Reyes Montenegro – a leader of the Union of Workers and Employees of Public Services was murdered in Colombia.

Alba Bermeo Puin – an indigenous leader and environmental defender in Ecuador was murdered when five months pregnant.

Mursal Nabizada – a former female member of Afghanistan’s parliament and women’s rights campaigner murdered at her home.

This is not an exhaustive list by any stretch of the imagination. Compiling the names and profiles of women who have been killed as a result of their right to exercise freedom of expression is almost impossible, not least because of the nature of the repressive regimes which too many people live under. But every name represents thousands of others who day in, day out put their lives at risk to speak truth to power. They were mothers, grandmothers, daughters, nieces, granddaughters, sisters, aunts, friends, partners, wives.

To their families, they were the centre of the world. To us, today, their stories bring fear and inspiration in equal measure. They are heroes whose bravery we should all seek to emulate.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winner and 2018 Journalism Fellow Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes at the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

“Despite my fears and the pain that violence has left in my country, it has been wonderful to see that it has been worthwhile to dream in a world with so much solidarity,” Wendy Funes, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Journalism, told Index on Censorship.

Freedom of expression has suffered a steep decline in Honduras, a country where 70 journalists have been killed over the last nine years, with Gabriel Hernández’s murder on 17 March marking the first of 2019. Wendy Funes, an investigative reporter who runs her own online news website, Reporteros de Investigacion, is one of the few remaining journalists in the country that continues reporting and investigating issues despite the immense pressure to remain silent.

As a woman journalist in Honduras, a country in which gender-based violence is a serious issue, as is violence against journalists, Funes finds it important to attend events for women in leadership, such as the one she attended in Mexico City with the Center for Women’s Global Leadership.

“It helped me to realise that I am not alone in the continent and to know that there are other places with women who are specialised and do methodical and rigorous work,” said Funes.

Although she has faced a great deal of adversity as a woman journalist, Funes considers herself lucky having been given the opportunity to study and have a career in journalism, when seven out of every ten Hondurans live in poverty, with more than a million children without access to school and a small percentage of people who finish high school.

2019 is proving to be a busy year for Funes as she undertakes a new project, Sembrando el Periodismo de Investigacion en Honduras, with the help of a grant from National Endowment for Democracy. The project consists of four major investigations, two of which Funes and her team are currently working on.

The first is an investigation into the Trans 450, a transmetro that was promised to Hondurans and cost them $9 million, but has not been put into operation yet. The second investigation examines the impunity on aggressions against freedom of expression.

“The NED project is our first significant project and the support and respect they have shown for our work is really important to us,” said Funes.

The biggest project Funes has planned for the future, however, is the building of a Centre for Investigative Journalism that will be the first centre of its kind in Honduras.

“We want the office to become a training space for press and media professionals, advocates, professionals from universities, and academics who wish to learn,” said Funes.

In preparation for building the centre, Funes and her team are working with Factum magazine of El Salvador to train journalists and students. They will hold the first workshop in April of this year and the hope is that they will develop a network of journalists that will then serve as the foundation for the Centre for Investigative Journalism.

“For now, our priority is to strengthen our office and our business model, to nurture alliances and strengthen the network that will one day become the centre we are talking about,” said Funes.

Being an Index fellow has opened up many new opportunities for Funes, but has also renewed her own sense of confidence in herself as a woman and as a journalist.

“Index appeared in my life as a gift of providence and helped me at a very fundamental moment because the award coincided with the year I made the decision found my own newspaper,” said Funes. “They showcased me and my work and many more people followed in encouraging and supporting me.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1554114253076-1aebf9f6-f8dd-7″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winner and 2018 Journalism Fellow Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes at the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards (Photo: Elina Kansikas)

“Violence is a way of keeping society under control because a lot of what people do or don’t do is a reaction to fear,” Wendy Funes, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Journalism, tells Index on Censorship. “It becomes an indirect method of control, not just over society, but journalism as well.”

Funes worries this kind of violence has become “normalised” in Honduras and says the shooting and wounding of journalist Geovanny Sierra — who has survived numerous attempts on his life — by military police while covering protests of electoral fraud in late November is just the latest example. The Honduran authorities issued a statement saying that law enforcement was attacked first, which is why they started shooting. “With this they have justified the crime,” Funes says, adding that nothing is being done about the attacks on journalists in the country: “The most terrible thing is the impunity that exists because if something like this happened in another country it would a scandal, but here it is already forgotten.”

Funes is no stranger to covering either corruption or protest and has had her own brushes with heavy-handed state forces, although she says for the most part she has been lucky. “I’ve had training opportunities in self-protection and security,” she says. “I am also very cautious — I try to plan my routes and if I go inter dangerous areas, I try to have a safety protocol, to have alliances with civil society groups, so if something happens to me I can let them know.”

Recently, Funes’ investigative website Reporteros de Investigacion has been focusing on issues such as human trafficking, violence against student protesters, femicide and the high-level cocaine trafficking case involving Juan Antonio Hernández, brother of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández. The website has also been covering the caravan of people fleeing persecution, poverty and violence in the country. “They are facing a very cruel situation,” Funes says.

Honduran migrant Daniel Portillo

Although Reporteros de Investigacion doesn’t have the resources to cross the border, it has been working closely with some of those who have fled, such as 25-year-old Daniel Portillo, who left Honduras in search of the “American dream”. Portillo is now in Mexico. “He has found someone who works with migrants and helps migrants,” Funes, who first met him when she was covering protests in San Pedro Sula, a city in the northwest of Honduras, said. “He is a young person with a lot of leadership qualities, a lot of desire to advocate for other young people.”

While in Honduras Portillo organised sports tournaments in an area controlled by the criminal gang MS-13. “He resisted joining the gang,” Funes says. “He was always trying to negotiate with them so that he could help other young people so they wouldn’t get into drugs or alcohol.”

Writing in Reporteros de Investigacion, Portillo explains the difficulty of explaining to his young daughter that he left so she could have a better future: “If God allows it, we will see each other again or else, I am writing this letter to you in case unfortunately they killed me on the way and buried me; my heart is that of a warrior and I will continue forward, whatever happens, my mother suffers for my departure.”

“He told me that he has seen many people carved up since he was a child,” Funes tells Index. “Violence weighed on his psyche and made him very vulnerable young person. He told me that he looked for employment in Honduras, and when he could not find he decided to migrate with the caravan.”

It is such vulnerability that makes poor Hondurans so susceptible to human trafficking. “It’s like Russian roulette,” Funes says. “I have come to realise that there are many Hondurans who have an eagerness to migrate to the USA, but have ended up staying in countries like El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Belize and have become victims of sexual exploitation, domestic service and forced matrimonies as they flee from gangs and narco-politics. Some of the people who have left come back mutilated because they lose limbs on the trains.”

For those that do make it to the USA, they face discrimination, but at least they have the opportunity for better salaries, with which they can send money to their families struggling back home, Funes says. These remittances play a key role in sustaining the Honduran economy. In May 2018 Hondurans abroad sent back an all-time high of $456.2 million in a single month.

While Funes would like to see more Hondurans stay at home, not only to avoid the very real risks that come with being a migrant, but also to fight for real change, she is all too aware of why people choose instead to leave. “You have to work five times harder than a corrupt individual to be able to sustain yourself and get ahead in Honduras. This economic model displaces the most vulnerable individuals.”

Much of what Funes and her team do over the next year will be geared towards her dream of founding a centre of investigative journalism, including training journalists and students with the help of Factum magazine in El Salvador. “This will bring together many different journalists who want to transform Honduras with investigative journalism,” Funes says.

With a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy, Funes and her team will also work on a project called Sembrando el Periodismo de Investigación en Honduras (Sowing Investigative Journalism In Honduras), which will involve four major investigations over the course of 2019.

“Many of the things that I dreamt of happening one day, in an idealistic way, have become reality, all thanks to Index,” Funes adds. “Solidarity, love and friendship are really the things that can move this world, and that is what Index is made of with all of the support they have extended to me.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1561460137741-61f82764-3b8a-4″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

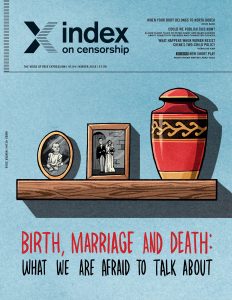

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Vital moments during our lifetimes are complicated by taboos about what we can and can’t talk about, and we end up making the wrong decisions just because we don’t get the full picture, says Rachael Jolley in the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Birth, Marriage and Death, the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos, especially around death and illness, can stop people asking for help or finding support in times of crisis” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Birth, Marriage and Death” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores taboos surrounding birth, marriage and death. What are we afraid to talk about?

With: Liwaa Yazji, Karoline Kan, Jieun Baek[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]