11 Dec 2017 | News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Fifty years after 1968, the year of protests, increasing attacks on the right to assembly must be addressed says Rachael Jolley”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Close to where I live is a school named after an important protester of his age, John Ball. Ball was the co-leader of the 14th century Peasants’ Revolt, which looked for better conditions for the English poor and took to the streets to make that point. Masses walked from Kent to the edges of London, where Ball preached to the crowds. He argued against the poor being told where they could and couldn’t live, against being told what jobs they were allowed to pursue, and what they were allowed to wear. His basic demands were more equality, and more opportunity, a fairly modern message.

For challenging the status quo, Ball was put on trial and then put to death.

These protesters saw the right to assembly as a method for those who were not in power to speak out against the conditions in which they were expected to live and taxes they were expected to pay. In most countries today protest is still just that; a method of calling for change that people hope and believe will make life better.

However, in the 21st century the UK authorities, thankfully, do not believe protesters should be put to death for asserting their right to debate something in public, to call for laws to be modified or overturned, or for ridiculing a government decision.

Sadly though this basic right, the right to protest, is under threat in democracies, as well as, less surprisingly, in authoritarian states.

Fifty years after 1968, a year of significant protests around the world, is a good moment to take stock of the ways the right to assembly is being eroded and why it is worth fighting for.

In those 50 years have we become lazier about speaking out about our rights or dissatisfactions? Do we just expect the state to protect our individual liberties? Or do we just feel this basic democratic right is not important?

Most of the big leaps forward in societies have not happened without a struggle. The fall of dictatorships in Latin America, the end of apartheid, the right of women to vote, and more recently gay marriage, have partly come about because the public placed pressure on their governments by publicly showing dissatisfaction about the status quo. In other words, public protests were part of the story of major social change, and in doing so challenged those in power to listen.

Rigid and deferential societies, such as China, do not take kindly to people gathering in the street and telling the grand leaders that they are wrong. And with China racheting up its censorship and control, it’s no wonder that protesters risk punishment for public protest.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protecting protest is vital, even if it doesn’t feel important today. ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

But it is not just China where the right to protest is not being protected. Our special report on the UK discovers that public squares in Bristol and other major cities are being handed over to private companies to manage for hundreds of years, giving away basic democratic rights like freedom of speech and assembly without so much as a backwards glance.

Leading legal academics revealed to Index that it was impossible to track this shift of public spaces into private hands in detail, as it was not being mapped as it would in other Western countries. As councils shrug off their responsibilities for historic city squares that have been at the centre of shaping those cities, they are also lightly handing over their responsibilities for public democracy, for the right to assembly and for local powers to be challenged.

The Bristol Alliance, which already controls one central shopping district with a 250-year lease, is now seeking to take over two central thoroughfares as part of a 100,000-square-metre deal (see page 15). And the people who are deciding to hand them over are elected representatives.

In the USA, where a similar shift has happened with private companies taking over the management of town squares, the right to protest and to free speech has, in many cases, been protected as part of the deal. But in the UK those hard-fought-for rights are being thrown away.

Another significant anniversary in 2018 is the centenary of the right to vote for British women over 30. That right came after decades of protests. Those suffragettes, if they were alive today, would not look kindly on English city councils who are giving away the rights of their ancestors to assemble and argue in public arenas.

For a swift lesson in why defending the right to assembly is vital, look to Duncan Tucker’s report on how protesters in Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil are facing increasing threats, tear gas and prison, just for publicly criticising those governments.

In Venezuela, where there are increasing food and medicine shortages, as well as escalating inflation, legislation is being introduced to criminalise protest.

As Tucker details on page 27 and 28, Mexican authorities have passed or submitted at least 17 local and federal initiatives to regulate demonstrations in the past three years.

Those in power across these countries are using these new laws to target minorities and those with the least power, as is typically the case throughout history. When the mainstream middle class take part in protest, the police often respond less dramatically. The lesson here is that throughout the centuries freedom of expression and freedom of assembly have been used to challenge deference and the elite, and are vital tools in our defences against corruption and authoritarianism. Protecting protest is vital, even if it doesn’t feel important today. Tomorrow when it is gone, it could well be too late.

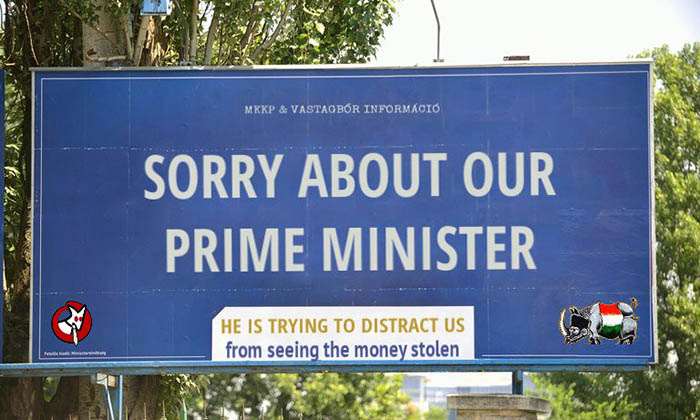

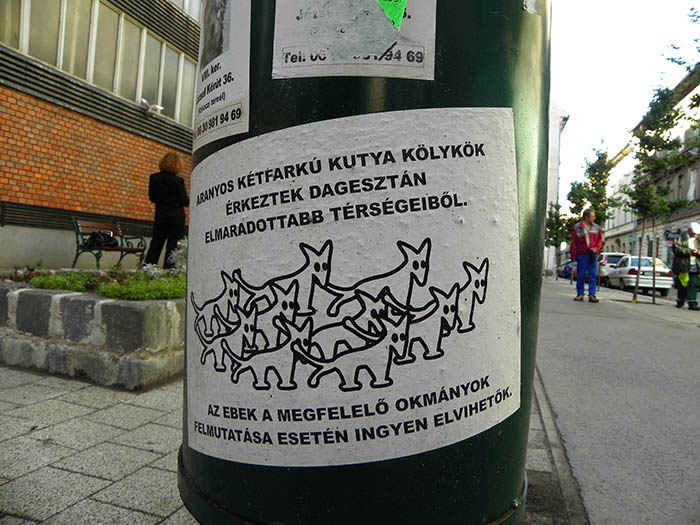

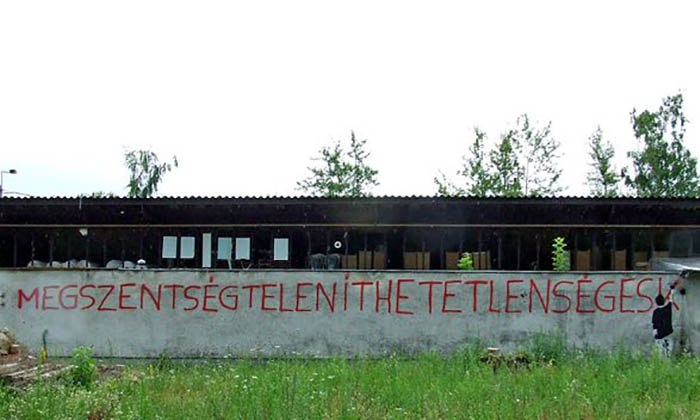

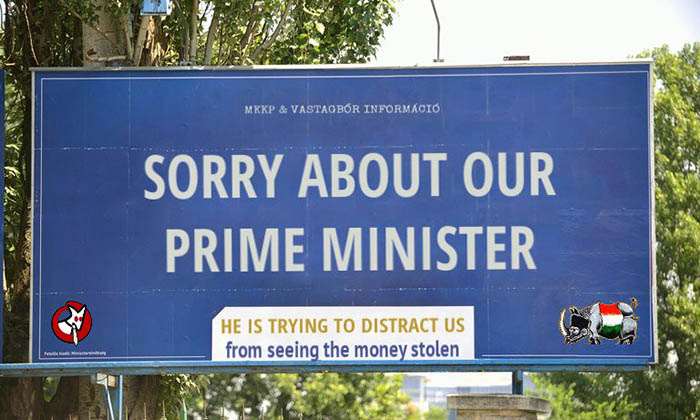

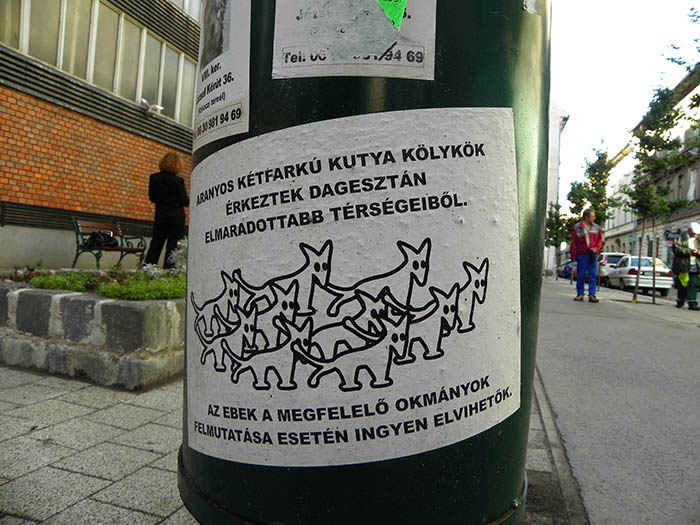

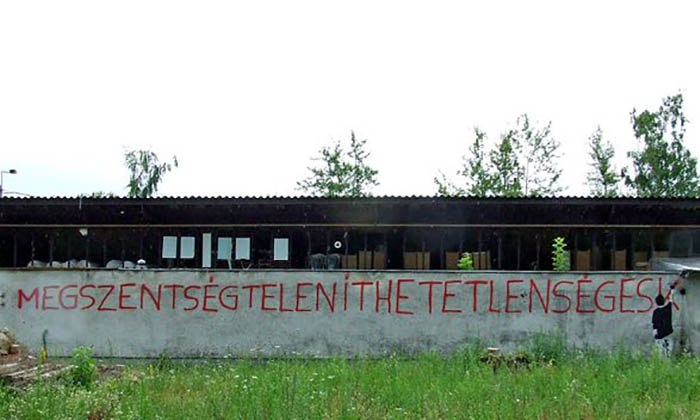

But it is not all bad news. We are also seeing the rise of extreme creativity in bringing protests to a whole new audience in 2017. From photos of cow masks in India to satirical election posters from the Two-Tailed Dog Party in Hungary, new techniques have the power to use dangerous levels of humour and political satire to hit the pressure points of politicians. These clever and powerful techniques have shown protest is not a dying art, but it can come back and bite the powers that be on the bum in an expected fashion. And that’s to be celebrated in 2018, a year which remembers all things protest.

Finally, don’t miss our amazing exclusive this issue, a brand new short story by the award-winning writer Ariel Dorfman, who imagines a meeting between Shakespeare and Cervantes, two of his heroes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91582″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228808534472″][vc_custom_heading text=”Uruguay 1968-88″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228808534472|||”][vc_column_text]June 1988

In 1968 she was a student and a political activist; in 1972 she was arrested, tortured and held for four years; then began the years of exile.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94296″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228108533158″][vc_custom_heading text=”The girl athlete” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228108533158|||”][vc_column_text]February 1981

Unable to publish his work in Prague since the cultural freeze following the Soviet invasion in 1968, Ivan Klíma, has his short story published by Index. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422017716062″][vc_custom_heading text=”Cement protesters” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422017716062|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Protesters casting their feet in concrete are grabbing attention in Indonesia and inspiring other communities to challenge the government using new tactics.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Sep 2017 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Viktor Orban (Credit: European People’s Party)

As Hungary prepares for parliamentary elections, independent journalists have become a target of the pro-government media outlets. This follows a speech by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban at the end of July at Tusványos, the annual Fidesz jamboree in Băile Tușnad, Romania, during which he said: “We must stand our ground against the Soros mafia network and bureaucrats in Brussels, and will have to go to battle against the media they operate in the coming months.”

Orban’s message at Tusványos is considered a preview of what to expect from the Hungarian government in the following months. A few days after the speech, Magyar Nemzet daily reported that the prime minister’s words signal a clear change in tactics: instead of defaming independent media outlets and their owners, pro-government media outlets started going after prominent journalists, known for their work of exposing the corruption of the Hungarian government.

During September 2017, pro-government media outlets started publishing articles discrediting leading Hungarian journalists critical to Orban’s regime.

On 5 September 2017, 888.hu published a list of journalists accused of being “mouthpieces” for George Soros, who has been called a “national security risk” and a “public enemy” by Orban for allegedly supporting the mass immigration of Muslims into Europe.

“The international media, with a few exceptions, generally write bad things about the government because a small minority with great media influence does everything to tarnish the reputation of Hungary in front of the world — prestige that has been built over hundreds of years by patriots,” 888.hu wrote.

Among those listed are Lili Bayer, a journalist working for Politico, László Balogh, a Pulitzer-winner photographer, Márton Dunai, Gergely Szakács and Sándor Pető, journalists working for the Reuters news agency, as well as Zoltán Simon, a journalist working for Bloomberg, and ZDF producer István Sinkovicz.

“The article is indicative of the extent to which the pro-government press seems willing to carry out the political orders of prime minister Viktor Orbán,” Budapest Beacon commented, adding that the editor in chief of 888.hu is Gábor G. Fodor, deputy chairman of Századvég Foundation’s board of trustees. Századvég is a think-tank and consultancy that has been embroiled in numerous scandals involving large government orders since 2010. The publisher of 888.hu is Modern Media Group Zrt., a company owned by Árpád Habony, an informal advisor to the prime minister.

The list was condemned by the 3,500-member National Association of Hungarian Journalists (MUOSZ). The body said that there is no evidence of any contact between Soros and the journalists named in the piece. “Stigmatising colleagues by using listing methods that hark back to former anti-democratic times is far from the practice of democratic journalism and informing (the public),” said MUOSZ.

The campaign against journalists continued on 11 September 2017 with a piece on 888.hu attacking Gergely Brückner, one of Hungary’s leading business journalists working at index.hu. The piece accused Brückner of writing an article about the political-diplomatic background of several millions of dollars transferred to Hungary from an Azerbaijani slush fund without any evidence.

“I was not particularly bothered by the editorial, although I don’t think he understands correctly where the trenches in the Hungarian media landscape are,” Gergely Brückner told Index on Censorship. “He also exaggerates my importance (of course, I felt flattered), and for sure he does misunderstand the goals I had with my articles.”

“It is known that the ruling party is always looking for enemies, these being refugees, Soros, the EU, NGOs and independent journalists, all of which are under attack,” Brückner added. “This is how they are trying to keep their core voters engaged.”

Unfortunately, ordinary media consumers have a difficulty in making a distinction between independent, fact-based journalism and biased, post-truth journalism, as Brückner explains. “I am not disturbed at being targeted and it does not influence my work or my sources. They had an obviously exaggerated opinion about me, but they did not have false statements. In the latter case, I would seek legal redress.”

On 14 September 2017, Attila Bátorfy, a data journalist at investigative website Atlatszo.hu and research fellow at CEU’s Center for Media and Communication Studies was also the target of a defamatory article published on an obscure blog, Tűzfalcsoport. The piece, illustrated with a photo of enlarged mites, is claiming that Bátorfy’s piece on the spread of Russian propaganda in Hungary is based on faulty evidence.

A day later, on 15 September 2015, Pesti Srácok, another website close to the government published an article about András Földes, a journalist working for index.hu who reported extensively on the migration crisis. The piece is a list of Földes’s more important reports, along with “ironic” commentary.

“When he goes to war zones, he watchfully takes a peek on the trenches, carefully avoiding danger, then he presents the things he saw as he wishes (…). His extraordinary talent is also shown by the fact that he believes anything to 17-year old immigrant men born on 1 January. At least we hope he naively believes the overstatements he writes about, and these (overstatements) are not invented by him,” the article goes.

Even if the readership of such a blog or website is relatively small, these articles are usually echoed in the media universe loyal to Orban and are often referenced by the public media as well, meaning that the allegations reach a considerable audience.

The recent defamatory pieces are only the tip of the iceberg of the attacks on press freedom in Hungary. Since 2010, the Hungarian government led by Orbán is working systematically to silence critical voices by changing the legal framework regarding media, redrawing the advertising market, introducing preferential taxes that only hit certain, independent broadcasters, buying up media companies, or simply closing them down, as happened with the largest opposition newspaper, Népszabadság.

The most alarming recent incidents regarding press freedom in Hungary:

Police check IDs of TV crew filming new PM office

Journalist assaulted at a Fidesz public forum

Largest opposition daily suspended

Parliamentary amendment restricts access to public information[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506503807710-1289f6d8-e51b-2″ taxonomies=”2942″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Apr 2017 | Academic Freedom, Hungary, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As a new law passed by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán’s government threatens the existence of Central European University in Budapest, 70,000 people marched in protest in the capital to save it as part of the #IStandWithCEU campaign.

Among those offering supportto protect the academic freedom of one of central Europe’s most prominent graduate universities, either by writing letters or demonstrating, include more than 20 Nobel Laureates including Mario Vargas Llosa, hundreds of academics worldwide, the European Commission, the UN, the governments of France and Germany, 11 US Senators, Noam Chomsky and Kofi Annan.

Whilst the amendment, which will effectively force CEU to shut, has been signed into statute by Hungarian president Janos Ader, the university hopes to challenge the law in the Hungary’s Constitutional Court.

In a video released on 20 April, Michael Ignatieff, president and rector of CEU, said: “Three weeks ago this university was attacked by a government who tabled legislation that would effectively shut us down. We fought back and the reception around the world has been just magnificent.”

He added: “Academic freedom is one of the values we just can’t compromise.”

Orsolya Lehotai, a masters student at CEU and one of the organisers of the street protest movement Freedom for Education, told Index that initially the small group of students had hoped to “mimic democratic society” and stop the law passing in its original form.

“So far in the seven years of the Orbán government, whenever there was big opposition to something, people have taken to the streets and this has actually changed legislation, so we decided it would show a little power if we were to have people in the streets about this,” Lehotai said. “Back then [at the first protest] we were unsure when the parliamentary debate was to happen but we had had news that it was to happen on a fast-track, which to us was outrageous.”

Despite the protests and international criticism, the Hungarian government said that the law is designed to correct “irregularities” in the way some foreign institutions run campuses. Government officials maintain that the legislation is not politically motivated.

Áron Tábor is a Fulbright scholar and another CEU student who has taken to the streets. He spoke to Index about the absurdity of the Hungarian government’s stance: “This is one university, where the language is instruction is English and the programs run according to the American system.The government says that CEU is a ‘phantom university’, or even a ‘mailbox university’, which doesn’t do any real teaching, but only issues American degrees from a distance. This is a ridiculous claim.”

Gergő Brückner, a journalist at Index.hu described the political paranoia that lies behind the new laws: “One important thing to know is that Fidesz doesn’t like anything that is not part of their own Fidesz system. You can be a famous filmmaker, a university researcher or an Olympic medal winner but you must, for them, be the part of the national circle of Fidesz.”

“If you are an independent and well-funded American university – then you are not controlled, and you can easily be portrayed as a kind of enemy,” he added.

Since its establishment in 1991, CEU has made no secret of its commitment to freedom of expression. It was founded by a group of intellectuals including George Soros, who has been much criticised by Orbán.

The university was designed to reinforce democratic ideals in an area of the world just emerging from communist control. This ethos continues: in February the annual president’s lecture at CEU was given by the University of Oxford academic Timothy Garton Ash who spoke on the topic of “Free Speech and the Defense of an Open Society”.

When the law comes into force, requirements for foreign higher education institutions to have a campus in their home country mean that it will be impossible for CEU to continue operating.

Similarly, requiring a bilateral agreement between the government of the country involved, and the Hungarian government is a huge obstacle, as in CEU’s case this would be the USA but the US federal government has made it clear that it is not within their competence to negotiate this.

More generally, the ability of the Hungarian government to block any agreement raises worrying possibilities, too. Professor Jan Kubik told Index: “A democratic government has no business in the area of education, particularly higher education, except for providing funds for it. When a government tries to play an arbiter, dictating who does and who does not have the right to teach that is a sure sign of authoritarian tendency.”

Kubik, director of University College London’s School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies, along with over a thousand other international academics, has strongly criticised the new legislation, and his department is holding a rally in London on April 26.

He has also signed an open letter published in the Financial Times.

He said: “Any governmental attempt to close down a university is always very troubling. An attack on a university in a country that has already been travelling on a path towards de-democratisation for a while is alarming.

“Universities are like canaries of freedom and independence of the public sphere. Their death or weakening signals trouble for this sphere, a sphere that is indispensable for democracy.”

With the international condemnation of the Lex CEU amendment and a likely protracted legal battle ahead, what Kubik called “a magnificent institution of higher learning, as devoted to the freedom of intellectual inquiry and high ethical standards as any of the best universities in the world” is not expected to shut its doors this year.

Meanwhile, those fighting for fundamental freedoms in Hungary will continue to challenge Orbán. European Commission vice president Frans Timmermans said, CEU has been a “pearl in the crown” of central Europe that he would “continue to fight for”, and for as long as global opinion remains so loudly behind CEU, Orbán will find it an institution difficult to silence. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493126838618-e2c5cf5d-d00a-0″ taxonomies=”2942″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Mar 2017 | Awards, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hungary’s high tide of populism was beaten back briefly in October 2016 when prime minister Viktor Orban’s referendum on closing the door on refugees was ruled invalid after just 44% of the population bothered to show up and vote.

The country’s Two-tailed Dog Party don’t take credit for the result, but were certainly part of the mass soft power endeavour that defeated the referendum, and they used a tact rarely seen in Hungarian politics today: humour.

They urged voters to “Vote invalidly!” by answering both yes and no. “A stupid answer to a stupid question.”

What officially became known as the Two-tailed Dog Party in 2006 has been around since 2000, when it was a group of street artists fronted by Gergely Kovács. In their current form they parody political discourse in Hungary with artistic stunts and creative campaigns.

The Two-tailed Dog is a vital alternative voice following the rise of Orban and is now a registered political party ready to contest in 2018’s parliamentary elections. They can no longer be written off as a joke.

When the prime minister started plastering Hungary with anti-immigrant posters with slogans like “If you come to Hungary, you may not take jobs away from Hungarians,” and “If you come to Hungary, you must respect our culture,” the Two-tailed Dog responded with a billboard campaign of their own: “If you are Hungary’s prime minister, you have to obey our laws,”; “Come to Hungary by all means, we’re already working in London.”

The lampooning was largely crowdfunded, and volunteers from around the country were on hand to erect 500 outdoor billboards and over 100,000 smaller posters.

When Orban introduced the national consultation on immigration and terrorism in 2015, as part of a series of xenophobic measures to repel tens of thousands of migrants and refugees, and plastered cities with anti-immigrant billboards, the Two-tailed Dog launched mock questionnaires and even more billboards and posters.

Relentlessly attempting to reinvigorate public debate and draw attention to under-covered taboo topics, the party’s recent efforts also include painting broken pavement to draw attention to a lack of public funding.

“It would be important for people to be able to discuss things again and for the atmosphere in the country to finally improve and change back to normal,” Kovács says.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490258649778{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/donate-heads-slider.jpg?id=75349) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490271092003-8af6e4a2-7218-9″ taxonomies=”8734″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]