11 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Kemel Aydogan’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Turkey. Credit: Mehmet Çakici

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, a Shakespeare special to mark the 400th anniversary of his death, takes a global look at the playwright’s influence, explores how censors have dealt with his works and also how performances have been used to tackle subjects that might otherwise have been off limits. Below some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

(For the more on the rest of the magazine, see full contents and subscription details here.)

Kaya Genç on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in Turkey

“When Turkish poet Can Yücel translated A Midsummer’s Night Dream, he saw the potential to reflect Turkey’s authoritarian climate in a way that would pass under the radar of the military intelligence’s hardworking censors. Like lovers in Shakespeare’s comedy who are tricked by fairies into falling in love with characters they actually dislike, his adaptation [which was staged in 1981 and led to the arrests of many of the actors] drew on the idea that Turkey’s people were forced by the state to love the authority figures that oppressed them the most. They were subjugated by the military patriarchy, the same way the play’s female and artisan characters were subjugated by Athenian patriarchy.

Kemal Aydoğan, the director of the latest Turkish adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described the work as ‘one of the most political plays ever written’. For Aydoğan, the scene in which the Amazonian queen Hippolyta is subjugated and taken hostage by the Theseus marks a turning point in the play. ‘That Hermia is not allowed to marry the man she loves but has to wed the man assigned to her by her father is another sign of women’s subjugation by men,’ he said. This, according to Aydoğan, is sadly familiar terrain for Turkey where women are frequently told by male politicians to know their place, keep silent and do as they are told.’ ”

Claire Rigby on Julius Caesar in Brazil

“In a Brazil seething with political intrigue, in which the impeachment proceedings currently facing President Dilma Rousseff are just the most visible tip of a profound turbulence which has gripped the country since her re-election in October 2014, director Roberto Alvim’s 2015 adaptation of Julius Caesar was inspired by a televised presidential debate he saw in the final days of the election campaign, in which centre-left Rousseff faced off against her centre-right opponent Aécio Neves. ‘I watched the debate as it became utterly polarised between Dilma and Aécio, and the famous clash between Mark Antony and Brutus instantly came to mind,’ he said. ‘It was the idea that the same facts can be drawn in such completely different ways by the power of speech: the power of the word to reframe the facts, and its central importance in the political game.’ ”

György Spiró on Richard III in Hungary

“Richard III was staged in Kaposvár, which had Hungary’s very best theatre at the time. This was 1982.

Charges were brought against the production, because the Earl of Richmond wore dark glasses. A few weeks earlier, on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared a state of emergency in Poland. For health reasons he wore sunglasses every time he appeared in public.”

Simon Callow on Hamlet under Stalin and the Nazis

“In 1941, Joseph Stalin banned Hamlet. The historian Arthur Mendel wrote: ‘The very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who intently scrutinized the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside ‘prompting,’ the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost ‘criminal’.’ Having Hamlet suppressed must have been a nasty shock for Russians: at least since the times of novelist and short story writer Ivan Turgenev, the Danish Prince had been identified with the Russian soul. Ten years earlier, Adolf Hitler had claimed the play as quintessentially Aryan, and described Nazi Germany as resembling Elizabethan England, in its youthfulness and vitality (unlike the allegedly decadent and moribund British Empire). In his Germany, Hamlet was reimagined as a proto-German warrior. Only weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared titled Shakespeare – A Germanic Writer.”

Natasha Joseph on Othello in South Africa

“In 1987, actress and director Janet Suzman decided to stage Othello in her native South Africa, bringing ‘the moor of Venice’ to life at Johannesburg’s iconic Market Theatre. It was just two years since Prime Minister PW Botha had repealed one of apartheid’s most reviled laws, the Immorality Act, which banned sexual relationships between people of different races. Even without the legislation, many white South Africans baulked at the idea of interracial desire. No wonder, then, that Suzman’s production attracted what she has described as ‘millions of bags full of hate letters from people who thought that this was an outrage’.

But in a country famous for sweeping censorship and restrictions on freedom of movement, speech and association, the play was not banned. Why? Because the apartheid government ‘would have been the laughing stock of the world if they had banned Shakespeare’, Suzman told Index on Censorship. ‘Any government would be really embarrassed to ban Shakespeare. The apartheid government was frightened of ridicule. Everyone is frightened of laughter.’ ”

For more articles on Shakespeare’s battle with power around the world, see our latest magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial). Copies are also available in excellent bookshops including at the BFI, Mag Culture and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon or a digital magazine on exacteditions.com. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

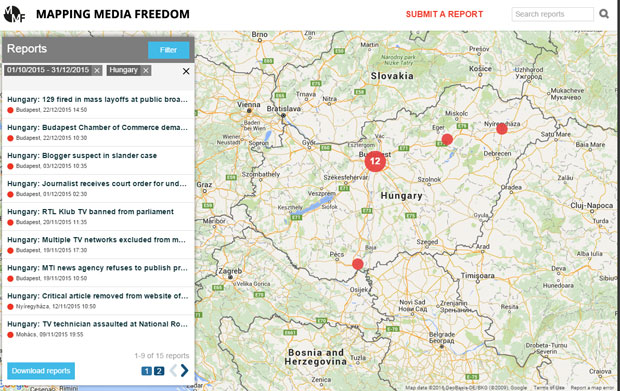

21 Jan 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Hungary’s media outlets are coming under increasing pressure from lawsuits, restrictions on what they can publish and high fees for freedom of information requests, according to a survey of the 15 verified reports to Index on Censorship’s media monitoring project during the fourth quarter of 2015.

The Mapping Media Freedom project, which identifies threats, violations and limitations faced by members of the press throughout the European Union, candidate states and neighbouring countries, has recorded 129 verified incidents in Hungary since May 2014. In the fourth quarter of 2015 the country had the second-highest total of verified reports among EU member states and the sixth highest total among the 38 countries monitored by Mapping Media Freedom.

In 2015, Hungary was ranked #65 (partially free) on the World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders. Only two EU member states, Greece and Bulgaria received a worse score.

In autumn 2015, the law governing freedom of information (FOI) was amended after a series of investigative reports uncovered wasteful government spending through FOI requests. Under the changes, the Hungarian government was granted sweeping new powers to withhold information and allowed the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “labour costs” associated with FOI queries. Critics warned that fees would prevent public interest journalism, and, in at least one case, it appears they were right.

In other cases, journalists have been sued for slander and issued court orders for undercover reporting on the refugee crisis.

Here are the 15 reports with links to more information.

- 22 December 2015: Budapest Chamber of Commerce demands high price to answer FOI request

The Budapest Chamber of Commerce (BCCI) asked for 3-5 million HUF ($10,356-16,352) to answer a freedom of information (FOI) request submitted by channel RTL Klub. The Budapest Chamber of Commerce and Industry said that the price will cover the salaries of 2-3 employees who would be given the task to respond to the FOI regarding BCCI’s spending and finances.

- 22 December 2015: 129 fired in mass layoffs at public broadcaster

Even the jobs of those who work for the government-friendly state broadcaster are far from being secure. On 22 December 2015, 129 employees were laid off by the umbrella company for public service broadcasters (MTVA) in pursuit of “operational rationalisation”.

Those fired included journalists, editors and foreign correspondents. According to the MTVA, the reason for the dismissal was the “better exploitation of synergies”, “increase of efficiency” and “cost reduction”.

- 3 December 2015: Blogger suspect in slander case

András Jámbor, a blogger is suspect in a slander case because he refuted the claims of Máté Kocsis, the mayor of Józsefváros (8th district of Budapest). In August 2015, Mayor Kocsis published a Facebook post alleging that the refugees have been making fires, littering, going on rampage, stealing and stabbing people in parks.

In response, Jámbor wrote a post for Kettős Mérce blog, disproving the mayor’s claims. He added that “Máté Kocsis is guilty of instigation and scare-mongering”. The mayor denounced him for slander.

On 3 December 2015, Jámbor confirmed to police that he is the author of the blog post and sustains the affirmations he made. The police took fingerprints and mugshots of the journalist.

- 1 December 2015: Journalist receives court order for undercover report on refugee camps

Gergely Nyilas, a journalist working for Hungarian online daily Index.hu, was summoned to court for his undercover report on refugee camp conditions published in August 2015.

The journalist reentered Hungary’s borders with a group of asylum seekers and, upon being detained, told the border guards that he was from Kyrgyzstan. Dressed in disguise, Nyilas reported on his treatment by border guards, the conditions at the Röszke camp, a bus ride and his experience at the police station in Győr. He eventually admitted he was Hungarian, at which point the police let him go, the Budapest Beacon reported.

Based on a police investigation, prosecutors first charged Nyilas with lying to law enforcement officials and forging official documents. The charges were then dropped but prosecutors still issued a legal reprimand against the journalist.

- 20 November 2015: Parliament speaker bans RTL Klub TV

On 20 November 2015, László Kövér, the speaker of the parliament has banned RTL Klub television from entering the parliament building, saying that the crew broke parliament rules on press coverage. According to Kövér, the journalists were filming in a corridor, where filming was forbidden, and then refused to leave the premises after they were repeatedly asked to.

The day before, on 19 November, RTL Klub was not allowed to participate at a press conference held by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg in parliament.

RTL Klub, along with other Hungarian media outlets such as 444.hu or hvg.hu, were not invited to the press conference, but RTL Klub journalists still showed up. They attempted to enter the room with the camera rolling but were denied access. This incident reportedly led to the ban on their access.

- 19 November 2015: Multiple TV networks excluded from major press conference

RTL Klub TV, 444.hu and hvg.hu journalists were not invited to a joint press conference held in parliament by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg.

RTL Klub journalists still attempted to attend by entering the room with a camera already rolling but were still barred from entering.

They were told that the meeting was “private”, and journalists were not allowed to ask questions. Bertalan Havasi, the press secretary for the Hungarian prime minister, told them that their pass was only for the plenary session and that they must leave. However, state media outlets like M1 were allowed live transmission of the press conference, and MTI, the Hungarian wire service also published a piece about the meeting.

- 19 November 2015: MTI news agency refuses to publish press release

Publicly funded news agency MTI refused to publish a press release by Hungarian Socialist Party vice president Zoltán Lukács, where he asked for a wealth gain investigation into István Tiborcz, the son-in-law of the Hungarian prime minister. MTI refused to publish the press release, claiming that István Tiborcz is not a public figure.

The business interests of the son-in-law of Prime Minister Victor Orbán are widely discussed in the Hungarian media, especially because companies connected to Tiborcz are frequently winning public procurement tenders.

- 12 November 2015: Critical article removed from website of local newspaper

An article about a photo manipulation of Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán was removed from the website of Szabolcs Online.

The article titled, A Mass of People Saluted Viktor Orbán at Nyíregyháza – Or Not?, had a photo showing that only two dozen people gathered around the Hungarian prime minister visiting the city of Nyíregyháza. Soon after the piece was published, it was removed from the szon.hu website. However, it was reportedly still available temporarily in Google cache.

The article was a reaction to a photo published by the state news agency, MTI, that was shot in such a way that it leaves the impression that there was a big crowd around the prime minister.

- 9 November 2015: TV technician assaulted at National Roma Council meeting

A technician working for Hír TV news television was assaulted at a meeting of the National Roma Council held in the city of Mohács. The technician was standing near a door, when the daughter of a member of the National Roma Council, hit him in the stomach, as she was leaving the room.

The mother of the aggressor, Jánosné Kis denied any wrongdoing, although her daughter actions were captured on film.

- 4 November 2015: Government could force media to employ secret service agents

Hungarian media is demanding that the government repeal a plan that could force newspapers, television and radio stations as well as online publications to add agents from the constitution protection office (national intelligence and counterintelligence) to their staff, the Associated Press reported.

The Hungarian publishers’ association claimed that if the draft proposal by the interior ministry is passed by parliament, it could “harshly interfere with and damage” media freedom, and would facilitate censorship. The association represents over 40 of Hungary’s largest media companies.

- 4 November 2015: Government official asks to criminalise defamation in media law

Geza Szocs, the cultural commissioner in the Hungarian Prime Ministry, has asked for a modification of Hungary’s media law that would criminalise defamation, in an article for mandiner.hu. Szocs has also asked for a stricter regulation of damages caused by defamatory articles.

The commissioner wrote the piece in response to a series of articles published by index.hu, which criticised the Hungary’s presence at the 2015 Milan World Fair, a project that Szocs was managing.

- 26 October 2015: Journalist told to delete photographs of government official

A journalist working on a profile of András Tállai, Hungarian secretary of state for municipalities, was asked to delete pictures he had taken of the politician eating scones.

“Don’t take pictures of the state secretary while he is eating,” a staff member told the journalist, who works for vs.hu.

The journalist briefly interviewed Tállai, who is also head of the Hungarian Tax Authority, in the township of Mezőkövesd, where the politician started the conversation by asking, “Why do you want to write a negative article about me?”. Tállai then smiled and asked the journalist, “You are registered at the Tax Authority, right?”

- 22 October 2015: Public radio censors interview with prominent historian

Editors at MR I Kossuth Rádió, part of Hungarian public radio, did not broadcast an interview with János M. Rainer, one of the most acclaimed historians on the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

“We don’t need a Nagy Imre-Rainer narrative!” was the justification given by one of the editors to censor the content, the reporter who interviewed Rainer claimed.

- 17 October 2015: State press agency refuses to publish opposition party press release

Hungarian state news agency MTI refused to publish a press release issued by Lehet Más a Politika (LMP), an opposition parliamentary party.

In the press release, LMP criticised MTI by stating the Hungarian government is spending more money every year on the news agency, yet MTI fails to meet the standards of impartiality and is being transformed into a government propaganda machine.

- 7 October 2015: National press barred from asking questions at conference

Hungarian journalists were not allowed to ask questions at a press conference held after a meeting between the Hungarian president János Áder and the PM of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic.

Only international journalists from Reuters and the Croatian state television were allowed to ask the politicians questions.

8 Jan 2016 | Belarus, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Turkey

The attacks on the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January set the tone for conditions for media professionals in 2015. Throughout the year, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom correspondents verified a total of 745 violations of media freedom across Europe.

From the murders of journalists in Russia, Poland and Turkey to the growing threat posed by far-right extremists in Germany and government interference in Hungary — right down to the increasingly harsh legal measures imposed on reporters right across the continent — Mapping Media Freedom exposed many difficulties media workers face in simply doing their jobs.

“Last year was a tumultuous one for press freedom; from the attacks at Charlie Hebdo to the refugee crisis-related aggressions, Index observed many threats to the media across Europe,” said Hannah Machlin, Index on Censorship’s project officer for the Mapping Media Freedom project. “To highlight the important cases and trends of the year, we’ve asked our correspondents, who have been carefully monitoring the region, to discuss one violation each that stood out to them.”

Belarus / 19 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Journalist blocked from shooting entrance to polling station

“It demonstrates the Belarusian authorities’ attitude to media as well as ‘transparency’ of the presidential election – the most important event in the current year.” — Ольга К.-Сехович

Greece / 15 verified reports in 2015

Four journalists detained and blocked from covering refugee operation

“This is important because it is typical ‘attempt to limit press freedom’, as the Union wrote in a statement and it is not very hopeful for the future. The way refugees and migrants are treated is very sensitive and media should not be prevented from covering this issue.” — Christina Vasilaki

Hungary / 57 verified reports in 2015

Serbian camera crew beaten by border police

“These physical attacks, the harsh treatment and detention of journalists are striking because the Hungarian government usually uses ‘soft censorship’ to control media and journalists, they rarely use brute force.” — Zoltan Sipos

Italy / 72 verified reports in 2015

Italian journalists face up to eight years in prison for corruption investigation

“I chose it because this case is really serious: the journalists Emiliano Fittipaldi and Gianluigi Nuzzi are facing up to eight years in prison for publishing books on corruption in the Vatican. This case could have a chilling effect on press freedom. It is really important that journalists investigate and they must be free to do that.” — Rossella Ricchiuti

Lithuania / 9 verified reports in 2015

Journalist repeatedly harassed and pushed out of local area

“I chose it because I found it relevant to my personal experience and the fellow journalist has been the only one to have responded to my hundreds of e-mails — including requests to fellow Lithuanian journalists to share their personal experience on media freedom.” — Linas Jegelevicius

Macedonia / 27 verified reports in 2015

Journalist publicly assaults another journalist

“I have chosen this incident because it best describes the recent trend not only in Macedonia and my other three designated countries, Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro, but also in the whole region. And that is polarization among journalists, more and more verbal and, like in this unique case, physical assaults among colleagues. It best describes the ongoing trend where journalists are not united in safeguarding public interest but are nothing more than a tool in the hands of political and financial elites. It describes the division between pro-opposition and pro-government journalists. It is a clear example of absolute deviation from the journalistic ethic.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Poland / 11 verified reports in 2015

Law on public service broadcasting removes independence guarantees

“The new media law, which was passed through Poland`s two-chamber parliament in the last week of December, constitutes a severe threat to pluralism of opinions in Poland, as it is aimed at streamlining public media along the lines of the PiS party that holds the overall majority. The law is currently only awaiting president Duda’s signature, who is a close PiS ally.” — Martha Otwinowski

Portugal / 9 verified reports in 2015

Two-thirds of newspaper employees will be laid off

“It’s a clear picture of the media in Portugal, which depends on investors who show no interest in a healthy, well-informed democracy, but rather in how owning a newspaper can help them achieve their goals — and when these are not met they don’t hesitate to jump boat, leaving hundreds unemployed.” — João de Almeida Dias

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Media freedom NGO recognised as foreign agent, faces closure

“The most important trend of the 2015 in Russia is the continuing pressure over the civil society. More than 100 Russian civil rights advocacy NGOs were recognized as organisations acting as foreign agents which leads to double control and reporting, to intimidation and insulting of activists, e.g., by the state-owned media. Many of them faced large fines and were forced to closure.” — Andrey Kalikh

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

TV2 loses counter claim to renew broadcasting license Roskomnadzor

“It illustrates the crackdown on independent local media, which can not fight against the state officials even if they have support from the audience and professional community.” — Ekaterina Buchneva

Serbia / 41 verified reports in 2015

Investigative journalist severely beaten with metal bars

“It’s a disgrace and a flash-back to Serbia’s dark past that a journalist, who’s well known for investigating high-level corruption, get’s beaten up with metal bars late at night by ‘unknown men’.” — Mitra Nazar

Turkey / 97 verified reports in 2015

Police storm offices of Koza İpek, interrupting broadcast

“The raid on Bugün and Kanaltürk’s offices just days ahead of parliamentary elections was a drastic example — broadcasts were cut by police and around 100 journalists ended up losing their jobs over the next month — of how the current Turkish government tries to strong-arm media organisations.” — Catherine Stupp

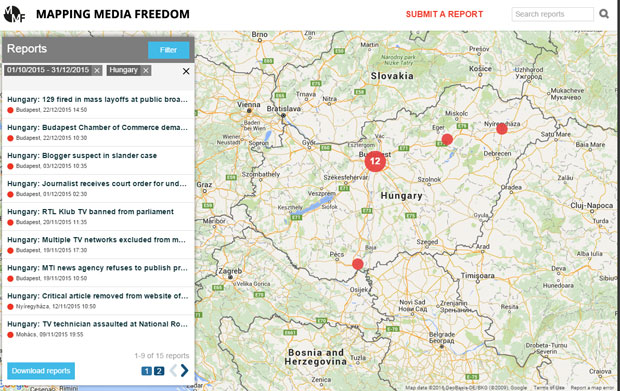

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

17 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, mobile, News and features

In February, journalists working at Hír TV, a Hungarian television news channel, and the daily Magyar Nemzet faced a difficult decision: they had 48 hours to decide whether to accept a job offer by the Hungarian public media. If they stayed, they found themselves “persona non grata” in the government circles. Even worse, their jobs and professional future became uncertain.

The story began when the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán had a fall out with his friend and long-time ally Lajos Simicska. The wealthy businessman – owner of a considerable media portfolio, with the Hír TV and Magyar Nemzet being the most important outlets – was the closest supporter of Orbán for 35 years.

There are many speculations, but nobody quite knows what the real reason for the dispute between the two is. The conflict became public when Simicska commented in the opposition-friendly newspaper Népszava that there will be a “total war” if the government adopts the so-called media tax that would affect his media interests.

As a reaction to Simicska’s comments, a number of his media executives resigned citing “reasons of conscience”. Among them was Gábor Liszkay, the editor-in-chief at the Magyar Nemzet, the second largest daily newspaper in Hungary, who took the paper’s entire senior management with him.

This was the moment when Simicska – who, until this point was known for his extremely discreet way of handling his business interests – went public and repeatedly called Viktor Orbán a “prick”. He also insinuated that Fidesz might murder him.

“On that day, without any formal procedure, they effectively fired the 250 people from Hír TV from the Regime of National Cooperation,” Péter Tarr, the deputy director of Hír TV, said in an interview.

In a few days, journalists and staff members, who until that point were close supporters of the Orbán government, were seen as “traitors” and “enemies” by the government. Their image became nearly as bad as the opposition journalists regularly labeled as “liberal”.

MTVA, the Hungarian public media facing criticism for being the mouthpiece of the Fidesz government, somehow obtained the names and salaries of Hír TV staff. Soon many journalists working at media outlets controlled by Simicska received well-paid job offers from MTVA.

“Nearly every staff member was offered a new job with considerably better pay, and the actual offer depended on his or her status within the editorial team, professional experience and reputation,” a member of senior management at Magyar Nemzet who wished to remain anonymous told Index on Censorship. “They clearly tried to collapse the media outlets controlled by Simicska.”

Some staff members said that the media portfolio controlled by Simicska is a sinking ship, and they should accept the offer while they can. “The curtains will soon fall and they will pour salt into the earth where the television once stood,” recounted Tarr.

“The strategy was to attract the key people and to wait for the editorial teams to collapse like a domino,” our source said. “They didn’t want to spend too much money. They speculated that later the majority of the journalists will appear on the job market anyway, and at that time they will be able to negotiate on totally different terms.”

Although many important staff members jumped ship from both Hír TV and Magyar Nemzet, the editorial teams managed to do the daily workload.

Once things calmed down, both media outlets found themselves free of the constant government control they were previously used to. Nobody from the Fidesz communication staff held meetings with the Hír TV senior management, instructing them who they should invite, what type of programming they should produce or what questions they should ask. As for Magyar Nemzet, the “commissars” (people who clearly had a political mission) disappeared from the editorial rooms.

“After March 15th […] we were free to decide all of this for ourselves and we now keep ourselves to the so-called BBC principles of professional journalism,” explained Tarr in the interview.

“There is a sense of freedom in the editorial room,” our source working at Magyar Nemzet said, adding: “There are no expectations that lead to self-censorship, nobody has to write things he considers problematic from a professional point of view.”

If the complete takeover failed, the government will make the life of journalists as hard as possible. “Some top officials refuse to talk to Magyar Nemzet, and the lower ranking government clerks are obeying the orders they received from the top,” the journalist said. “We can use only a few people from the government as sources.”

“At the public media, there are instructions that journalists working for Magyar Nemzet can not be invited, or employed. Before, I was invited very often to comment on foreign policy issues,” another senior staff member working for Magyar Nemzet told us. “Now I receive no invitations.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|