Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

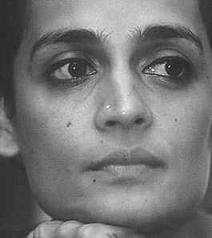

Arundhati Roy has been accused of sedition after claiming Kashmir was not part of India. Her comments may be controversial, but the real scandal is the law, says Salil Tripathi

(more…)

Booker prize-winner and human rights activist Arundhati Roy faces possible arrest following her remarks that Kashmir is not an integral part of India. India’s home ministry has told police in Delhi that a case of sedition may be registered against Roy and Kashmiri separatist Syed Ali Shah Geelani. In a statement that Roy released in response to the increasing movement against her she was unrepentant. This follows last week’s arrest of another Kashmiri separatist leader for allegedly organising anti–India protests.

The Booker prize-winning author responds to reports she may face sedition charges for her comments on Kashmir. Roy reiterates her belief that it is not an integral part of India

The Booker prize-winning author responds to reports she may face sedition charges for her comments on Kashmir. Roy reiterates her belief that it is not an integral part of India

I write this from Srinagar, Kashmir. This morning’s papers say that I may be arrested on charges of sedition for what I have said at recent public meetings on Kashmir. I said what millions of people here say every day. I said what I, as well as other commentators have written and said for years. Anybody who cares to read the transcripts of my speeches will see that they were fundamentally a call for justice. I spoke about justice for the people of Kashmir who live under one of the most brutal military occupations in the world; for Kashmiri Pandits who live out the tragedy of having been driven out of their homeland; for Dalit soldiers killed in Kashmir whose graves I visited on garbage heaps in their villages in Cuddalore; for the Indian poor who pay the price of this occupation in material ways and who are now learning to live in the terror of what is becoming a police state.

Yesterday I traveled to Shopian, the apple-town in South Kashmir which had remained closed for 47 days last year in protest against the brutal rape and murder of Asiya and Nilofer, the young women whose bodies were found in a shallow stream near their homes and whose murderers have still not been brought to justice. I met Shakeel, who is Nilofer’s husband and Asiya’s brother. We sat in a circle of people crazed with grief and anger who had lost hope that they would ever get ‘insaf‘–justice–from India, and now believed that Azadi–freedom– was their only hope. I met young stone pelters who had been shot through their eyes. I traveled with a young man who told me how three of his friends, teenagers in Anantnag district, had been taken into custody and had their finger-nails pulled out as punishment for throwing stones.

In the papers some have accused me of giving ‘hate-speeches’, of wanting India to break up. On the contrary, what I say comes from love and pride. It comes from not wanting people to be killed, raped, imprisoned or have their finger-nails pulled out in order to force them to say they are Indians. It comes from wanting to live in a society that is striving to be a just one. Pity the nation that has to silence its writers for speaking their minds. Pity the nation that needs to jail those who ask for justice, while communal killers, mass murderers, corporate scamsters, looters, rapists, and those who prey on the poorest of the poor, roam free.

The ever-readable Salil Tripathi, in his column in India’s Mint, points us to a disturbing story in Mumbai. The university there has withdrawn a book by renowned author Rohinton Mistry after a member of the right-wing Hindu Shiv Sena group complained it was offensive to his party.

…Rajan Waulkar, vice-chancellor of Mumbai University became the poster child of acquiescence to bullying when he hastily withdrew Mistry’s acclaimed previous novel Such A Long Journeyusing his emergency powers, after an undergraduate student aspiring for political leadership of the Shiv Sena’s youth wing, the Bharatiya Vidyarthi Sena, complained that the book made disparaging remarks against his party and his people. His claim to lead the youth wing rests on what he considers his inherent birthright—he is born in the Thackeray family.

Such A Long Journey is a thoughtful narrative about the scarcity-prone India at the cusp of the Bangladesh war of 1971, when Gustad Noble, a bank clerk, gets enmeshed in a conspiracy to assist the Mukti Bahini, the India-backed armed group fighting for Bangladesh’s freedom. He is brought to the shadowy world by an old acquaintance who is an intelligence officer, loosely based on the life of Rustom Nagarwala, who allegedly imitated prime minister Indira Gandhi’s voice and got a State Bank of India officer to hand him Rs. 60 lakh after the phone call, ostensibly for Bangladesh’s liberation.

The junior-most Thackeray’s complaint is vague, and political analysts might see his grandstanding as part of his desire (and his father Uddhav’s desire) to regain political ground, ever since Uddhav’s bête noire, his cousin Raj Thackeray, began wolfing down the Shiv Sena’s jhunka bhakar through his party, the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena.

Salil points out an uncomfortable truth for fundamentalists:

Hindu nationalists get riled when they are compared with Muslim leaders declaring fatwas. But the difference between those who want Such A Long Journey or Breathless in Bombay banned and the clerics who hate Rushdie—and the cartoonists of Jyllands-Posten—is marginal. Their threats chill free speech.