19 Jul 2019 | Magazine, News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”107971″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Andrew Graham-Yooll served as editor for the Index on Censorship magazine from 1989-1993. He was then, and remained until his death in 2019, committed to free expression and the free press around the world. In honour of his memory, Index is featuring some of the highlights of his writing for the magazine about his home country Argentina. The pieces featured cover a broad range of topics and events primarily related Argentinian art and journalism, and showcase Graham-Yooll’s fierce integrity and characteristic humor. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”94869″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227308532221″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Letter from Argentina

June 1973, vol. 2 issue: 2

“Censorship in Argentina is not a sin of the State, but a sickness of society”. Thus closes Andrew Graham-Yooll’s scathing indictment of censorship and self-censorship in the Argentinian press, in an environment where press controls are loosely organised but vicious.Graham-Yooll describes the routine torture and corruption in the criminal-justice system that the Argentinian press seems uninterested in, and expresses his opinion that, however damaging state censorship is, it is the fear and self-censorship it engenders in the press that is truly destorying Argentina’s soul.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”94773″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532398″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]The Argentinian press under Peron

March 1975, vol. 4 issue: 1

Andrew Graham-Yooll reflects on the record he kept of all the obstacles to press freedom and independence in Argentina during the early 1970s. He outlines, in broad strokes, the conflict between right- and left-wing branches of Peronism, and what the escalating conflict between the two–and the right wing’s eventual victory–meant for the operation of the Argentinian press. The press had faced restrictions and instability under Alejandro Augustin Lanusse and Hector Jose Campora that exploded into violence and direct government interference with print, radio, and television media under Raul Alberto Lastiri, Juan Peron himself, and his widow, Isabel Martinez de Peron.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”94399″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227908532905″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Arrests in Argentina

March 1979, vol. 8 issue: 2

Graham-Yooll takes a look into the fate of the nine workers at El Independiente, a left-of-center, nationalist local paper in the poor Argentinian province of La Rioja that “established itself on the wrong side of every provincial administration”. After Juan Peron was restored to power in 1973, the paper faced increasing harassment and frequent suspensions, until by 1976, El Independiente was permanently and forcibly closed, with seven of the nine workers arrested under dubious charges, some of their families in exile or tortured, and the remaining two workers missing. The Argentinian Newspaper Publishers’ Association demanded their release, but at the time of the article’s writing they were all still imprisoned.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”90901″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229508535825″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Coming Home

January 1995, vol. 7 issue: 2

This article is not an obituary, but it deals with the death of a gay Argentianian novelist, Manuel Puig. Puig died of AIDS in Mexico, a fact that Graham-Yooll was surprised to see mentioned in coverage of the artist and his work. Argentina’s social climate tolerates homosexuality to a degree, Graham-Yooll says, but only unobstrusive or plausibly deniable homosexuality. The brutal targeted repression under the military junta of “putos, guerrilleros, y faloperos” (queers, guerillas and drug addicts) is still in living memory for many gay Argentinians, and though the coverage of Puig could be a positive sign, discussion of homosexuality and gay rights was still not part of mainstream news coverage or culture in Argentina at the time of the article’s writing.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”90587″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220408537324″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]News From Patagonia

April 2004, vol. 33 issue: 2

In 2003, shortly before the article was written, Argentina’s Supreme Court struck down a law passed some twenty years earlier under the junta, which had made it illegal to provide broadcasting licences to community radio. The nominal grounds for that practice had been that it was easier to prevent the infiltration by the regime’s ideological enemies of commercial radio. However, before the law was struck down, its true raison d’etre had become the preservation of cronyism and political nepotism. Graham-Yooll uses the Supreme Court’s ruling as a chance to take stock of Argentina’s broadcasting landscape, with particular focus on the florshing of extra-legal, shoestring FM radio stations.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”89187″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220512331339490″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]The Pain and the Memory: The Legacy of Nunca Mas

February 2005, vol. 34 issue: 1

In 1984, Argentina’s National Commission on the Disappearance of Person released a report, Nunca Mas (Never Again), on the human rights abuses under the National Reorganisation Process between 1976 and 1983 that devastated many in the country. In this piece, written in 2012 Graham-Yooll discusses the abuses of the military and the many ways Argentina has attempted to grapple with the report, from the junta trials to a more recent photo exhibition of the atrocities. He shares a few of his own experiences from that time and describes how both dictatorship and report live on in Argentinian memory.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”89185″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220500125985″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Our Father, Who Art in Art

May 2005, vol. 34 issue: 2

In 2004, right after the Argentinian branch of the Catholic Church received praise for opening up politically, Leon Ferrari opened up an exhibition in Buenos Aires reviewing the collusion between the church and some of Latin America’s worst regimes over the centuries. Graham-Yooll describes some of the most important exhibit pieces and the extreme backlash the exhibit received from the church and laymenry–sometimes simultaneously, as in the entertaining story of a Christian vandal whose destruction of a piece was turned into an exhibit piece itself.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”89186″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220500125985″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Cumbia Villera: the Sound of the Slums

August 2005, vol. 34 issue: 3

A new genre of music is becoming popular in Latin America: the “politically incorrect” cumbia villera, a high-energy, hard-hitting new street music with a Carribbean beat. The lyrics to these songs, according to Graham-Yooll, are “vile and often violent”: they are filled with misogynistic abuse, incitement to prison breaks and riots, and enthusiastic encouragement of alcohol and hard drug use. For this reason, the Argentinain government at the time of the article was considering censoring cumbia villera, but in what Graham-Yooll asserts is a reflection of Argentina’s growing class divide, the music is gaining a mass following in the slums that seems unstoppable.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”89110″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422012456134″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]The Past in Hiding

September 2012, vol. 41 issue: 3

Nearly 40 years after the dirty war, Graham-Yooll examines two new books whose dialogue he believes represent hope that the record of atrocities committed by the junta can be known and Argentina can thus “come to terms” with its past. The first book, Final Disposal, is a set of nine interviews journalist Ceferino Reato conducted with members of the erstwhile regime in prison, in which those members display, according to Graham-Yooll, both generosity with information and a cold and brutal view of their own crimes. The second book, From Guilt to Forgiveness, is a personal account written by Norma Morandini, a former journalist and politician, about her personal journey from denial of what happened under the regime to a reckoning.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”80566″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422015605706″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]From murder to bureaucratic mayhem: After Argentina’s dictatorship, what happened next for the country’s journalists

September 2015, vol. 44 issue: 3

After Argentina emerged from under the rule of the military junta in 1983, press freedom improved considerably. Now, journalists are not murdered by the regime, but silenced through systemic harassment and the entangled web of cronyism. Graham-Yooll explains how the leader of Argentina at the time of the article, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, has developed a distinct and effect new “means of controlling the message”: not reactive censorship, but preemptive control of content through control of the ownership and cash flows of the media.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1565953044570-154320b2-e16d-10″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Feb 2019 | Magazine, News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Salman Rushdie. Credit: Fronteiras do Pensamento

On 14 February 1989 Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to execute author Salman Rushdie over the publication of The Satanic Verses, along with anyone else involved with the novel.

Published in the UK in 1988 by Viking Penguin, the book was met with widespread protest by those who accused Rushdie of blasphemy and unbelief. Death threats and a $6 million bounty on the author’s head saw him take on a 24-hour armed guard under the British government’s protection programme.

The book was soon banned in a number of countries, from Bangladesh to Venezuela, and many died in protests against its publication, including on 24 February when 12 people lost their lives in a riot in Bombay, India. Explosions went off across the UK, including at Liberty’s department store, which had a Penguin bookshop inside, and the Penguin store in York.

Book store chains including Barnes and Noble stopped selling the book, and copies were burned across the UK, first in Bolton where 7,000 Muslims gathered on 2 December 1988, then in Bradford in January 1989. In May 1989 between 15,000 to 20,000 people gathered in Parliament Square in London to burn Rushdie in effigy.

In October 1993, William Nygaard, the novel’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times outside his home in Oslo and seriously injured.

Rushdie came out of hiding after nine years, but as recently as February 2016, money has been raised to add to the fatwa, reminding the author that for many the Ayatollah’s ruling still stands.

Here, 30 years on, Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the issue of the fatwa, including two from Rushdie himself.

Cuba today, the March 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

World statement by the international committee for the defence of Salman Rushdie and his publishers

March 1989, vol. 18, issue 3

On 14 February the Ayatollah Khomeini called on all Muslims to seek out and execute Salman Rushdie, the author of The Satanic Verses, and all those involved in its publication. We, the undersigned, insofar as we defend the right to freedom of opinion and expression as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, declare that we also are involved in the publication. We are involved whether we approve the contents of the book or not. Nonetheless, we appreciate the distress the book has aroused and deeply regret the loss of life associated with the ensuing conflict.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Pandora’s box forced open

Amir Taheri

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

‘What Rushdie has done, as far as Muslim intellectuals are concerned, is to put their backs to the wall and force them to make the choice they have tried to avoid for so long’. Last year, when poor old Mr Manavi filled in his Penguin order form for 10 copies of Salman Rushdie’s third novel, The Satanic Verses, he could not have imagined that the book, described by its publishers as a reflection on the agonies of exile, would provoke one of the most bizarre diplomatic incidents in recent times. Mr Manavi had been selling Penguin books in Tehran for years. He had learned which authors to regard as safe and which ones to avoid at all costs.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Jihad for freedom

Wole Soyinka

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

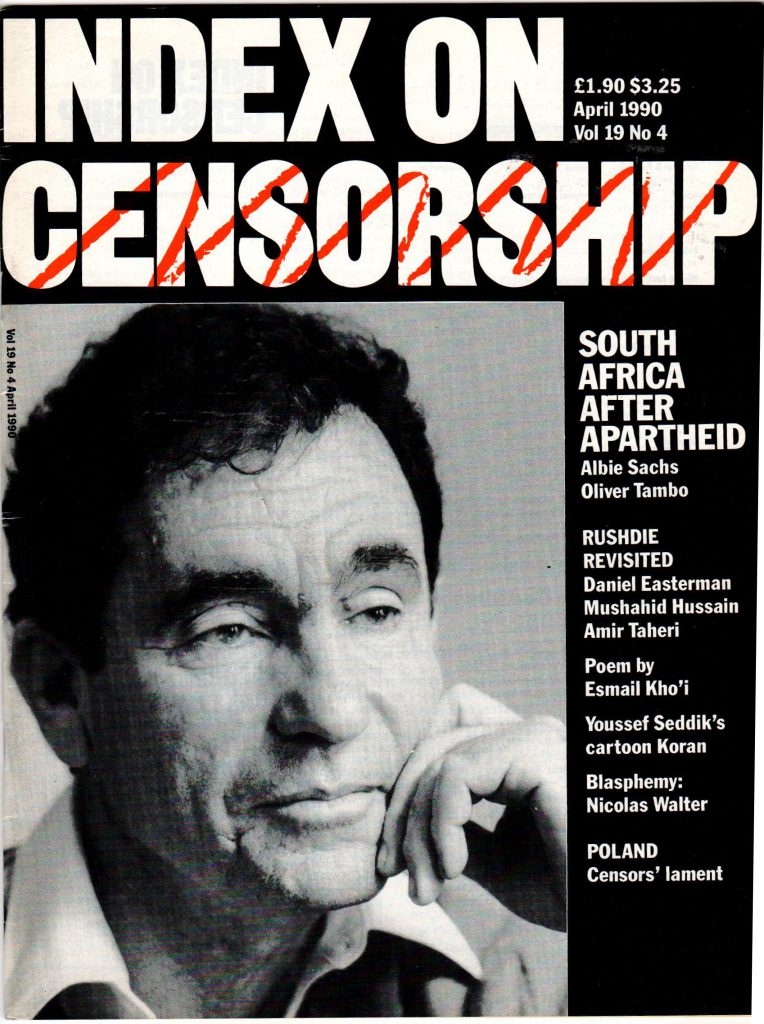

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Reflections on an invalid fatwah

Amir Taheri

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

Broadly speaking, three predictions were made. The first was that Khomeini’s attempt at exporting terror might goad world public opinion into a keener understanding of Iran’s tragedy since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The fact that the Ayatollah had executed thousands of people, including many writers and poets since his seizure of power in Tehran had provoked only mild rebuke from Western governments and public opinion. With the fatwa against Rushdie, we thought the whole world would mobilise against the ayatollah, turning his regime into an international pariah. Nothing of the kind happened, of course, and only one country, Britain, closed its embassy in Tehran – and that because the mullahs decided to sever.diplomatic ties. In the past twelve months Federal Germany and France have increased their trade with the Islamic Republic to the tune of II and 19 per cent respectively. The EEC countries and Japan have, in the meantime, provided the Islamic Republic with loans exceeding £2,000 million. The stream of European and Japanese businessmen and diplomats visiting Tehran turned into a mini-flood after Khomeini’s death last June.

Read the full article

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Salman Rushdie and political expediency

Adel Darwish

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

When I reviewed Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in September 1988, it never crossed my mind to make any reference to possible offence to Muslim readers, let alone to anticipate the unprecedented international crisis generated in the months that followed. I do not think I was naive – as an LBC radio reporter suggested when she interviewed me at the first public reading from The Satanic Verses in June 1989. On the contrary, I can claim more than many that I am able to understand what Mr Rushdie was trying to say in his book, and the way the crisis has developed. Like Mr Rushdie, I am a British writer, born to a Muslim family. Born in Egypt, I was educated and am employed in Britain, and have been preoccupied and engaged, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s, with the issues that Mr Rushdie has fought for and with which he seemed to be very much concerned in his book.

Read the full article

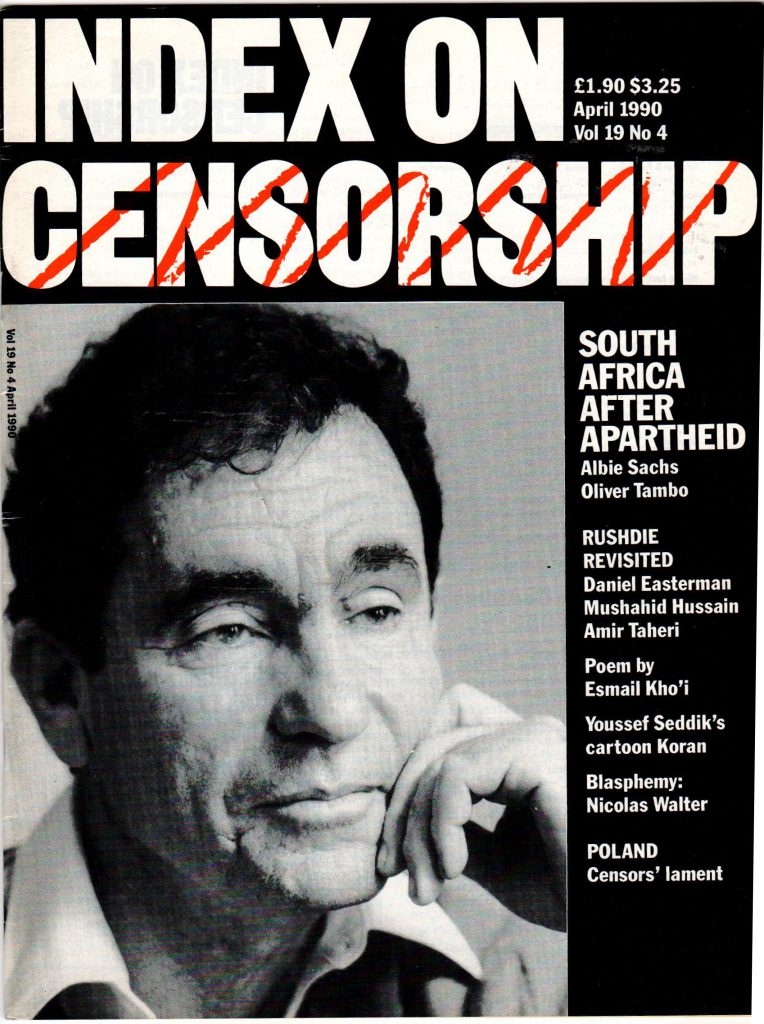

Azerbaijan, the February 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

My decision

Salman Rushdie

February 1991, vol. 20, issue 2

A man’s spiritual choices are a matter of conscience, arrived at after deep. reflection and in the privacy of his heart. They are not easy matters to speak of publicly. I should like, however, to say something about my decision to affirm the two central tenets of Islam — the oneness of God and the genuineness of the prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad —and thus to enter into the body of Islam after a lifetime spent outside it. Although I come from a Muslim family background, I was never brought up as a believer, and was raised in an atmosphere of what is broadly known as secular humanism. I still have the deepest respect for these principles. However, as I think anyone who studies my work will accept, I have been engaging more and more with religious belief, its importance and power, ever since my first novel used the Sufi poem Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-din Attar as a model. The Satanic Verses itself, with its portrait of the conflicts between the material and spiritual worlds, is a mirror of the conflict within myself.

Read the full article

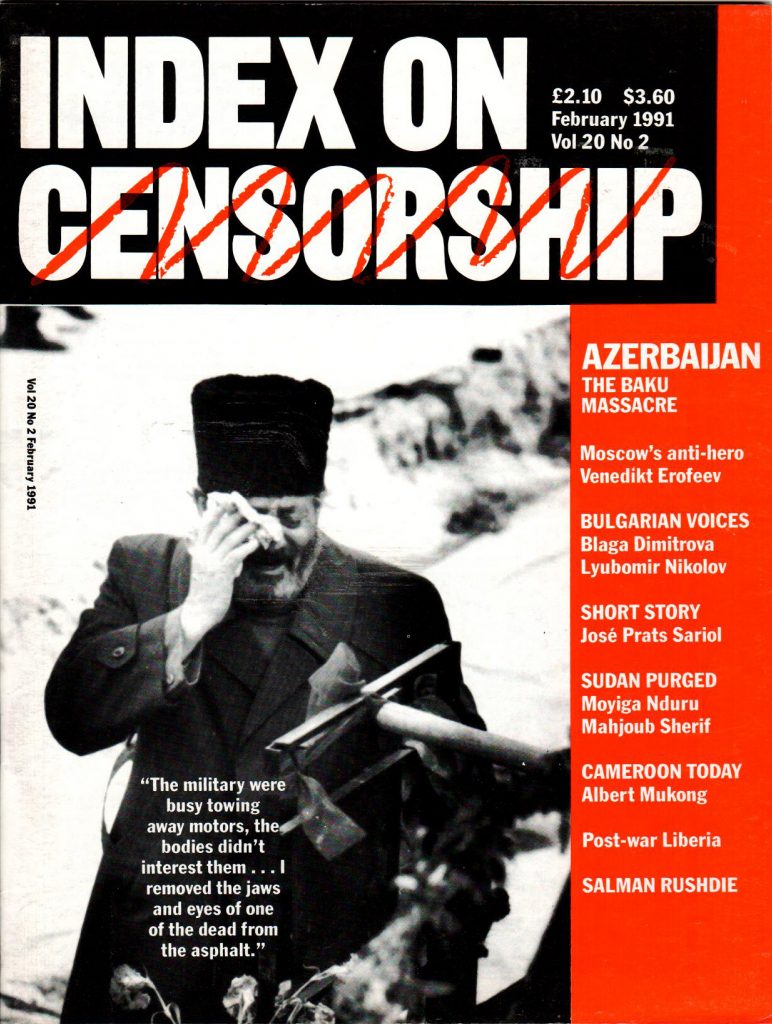

20th Anniversary: Reign of terror, the June 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Offending the high priests

Gunter Grass

June 1992, vol. 21, issue 6

When George Orwell returned from Spain in 1937, he brought with him the manuscript of Homage to Catalonia. It reflected the experiences he had gathered during the Civil War. At first, he was unable to find a publisher because a multitude of influential, left-wing intellectuals had no wish to acknowledge its shocking observations. They did not want to accept the Stalinist terror, the systematic liquidation of anarchists, Trotskyists and left-wing socialists. Orwell himself only narrowly escaped this terror. His stark accusations contradicted a world image of a flawless Soviet Union fighting against Fascism. Orwell’s report, this onslaught of terrible reality, tarnished the picture-book dream of Good and Evil. A year later, a bourgeois Western publisher brought out Homage to Catalonia; in the areas of Communist rule, Orwell’s works – among them the bitter Spanish truth – were banned for half a century. The minister responsible for state security= in the German Democratic Republic, right to its end, was Erich Mielke. During the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the Communist cadre to whom purge through liquidation became commonplace. A fighter for Spain with an extraordinary capacity for survival.

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Russia’s choice, the November-December 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Rushdie affair: Outrage in Oslo

Hakon Harket

November 1993, vol. 22, issue 10

The terrorist state of Iran must face the consequences of refusing to lift the fatwa that condemns Salman Rushdie, and those associated with his work, to death. When someone, in accordance with the express order of the fatwa, attempts to murder one of the damned, the obvious consequence is that Iran must be held responsible for the crime it has called for, at least until there is conclusive proof that no connection exists. The shooting of William Nygaard has reminded the Norwegian public of what the Rushdie affair is really about: life and death; the abuse of religion; the fiction of a free mind. This war of terror against freedom of speech is not one we can afford to lose. Since the nightmare clearly will not disappear of its own accord, it must be engaged head-on.

Read the full article

New censors, the March 1996 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

From Salman Rushdie

March 1996, vol. 25, issue 2

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

Shadow of the Fatwa

Kenan Malik

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

The Satanic Verses was, Salman Rushdie said in an interview before publication, a novel about ‘migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death’. It was also a satire on Islam, ‘a serious attempt’, in his words, ‘to write about religion and revelation from the point of view of a secular person’. For some that was unacceptable, turning the novel into ‘an inferior piece of hate literature’ as the British-Muslim philosopher Shabbir Akhtar put it. Within a month, The Satanic Verses had been banned in Rushdie’s native India, after protests from Islamic radicals. By the end of the year, protesters had burnt a copy of the novel on the streets of Bolton, in northern England. And then, on 14 February 1989, came the event that transformed the Rushdie affair – Ayatollah Khomeini issued his fatwa.’I inform all zealous Muslims of the world,’ proclaimed Iran’s spiritual leader, ‘that the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses – which has been compiled, printed and published in opposition to Islam, the prophet and the Quran – and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its contents are sentenced to death.’

Read the full article

The right to publish

The right to publish

Peter Mayer

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Penguin published Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses six months before Ayatollah Khomeini issues his fatwa. When we decided to continue publishing the novel in the aftermath, extraordinary pressures were focused on our company, based on fears for the author’s life and for the lives of everyone at Penguin around the world. This extended from Penguin’s management to editorial, warehouse, transport, administrative staff, the personnel in our bookshops and many others. The long-term political implications of that early signal regarding free speech in culturally diverse societies were not yet apparent to many when the Ayatollah, speaking not only for Iran but, seemingly, for all of Islam, issued his religious proclaimation.

Read the full article

Emblem of darkness

Emblem of darkness

Bernard-Henri Lévy

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Salman Rushdie was not yet the great man of letters that he has since become. He and I are, though, pretty much the same age. We share a passion for India and Pakistan, as well as the uncommon privilege of having known and written about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (Rushdie in Shame; I in Les Indes Rouges), the father of Benazir, former prime minister of Pakistan, executed ten years earlier in 1979 by General Zia. I had been watching from a distance, with infinite curiosity, the trajectory of this almost exact contemporary. One day, in February 1989, at the end of the afternoon, as I sat in a cafe in the South of France, in Saint Paul de Vence, with the French actor Yves Montand, sipping an orangeade, I heard the news: Ayatollah Khomeini, himself with only a few months to live, had just issued a fatwa, in which he condemned as an apostate the author of The Satanic Verses and invited all Muslims the world over to carry out the sentence, without delay.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1623240200822-8c1bcd36-9835-10″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Feb 2019 | Magazine, News, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Forty years ago, on 11 February 1979, the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, came to an end after millions of Iranians, from all backgrounds, took to the streets in protest at what they saw as an authoritarian, oppressive and lavish reign.

After decades of royal rule, and following 10 days of open revolt since the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to the country after 14 years of exile, Iran’s military stood down. With Pahlavi forced to leave the country, the Islamic Republic of Iran was declared in April 1979.

Here Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the revolution, an event that has since shaped the entire Middle East and has had a lasting impact to this day.

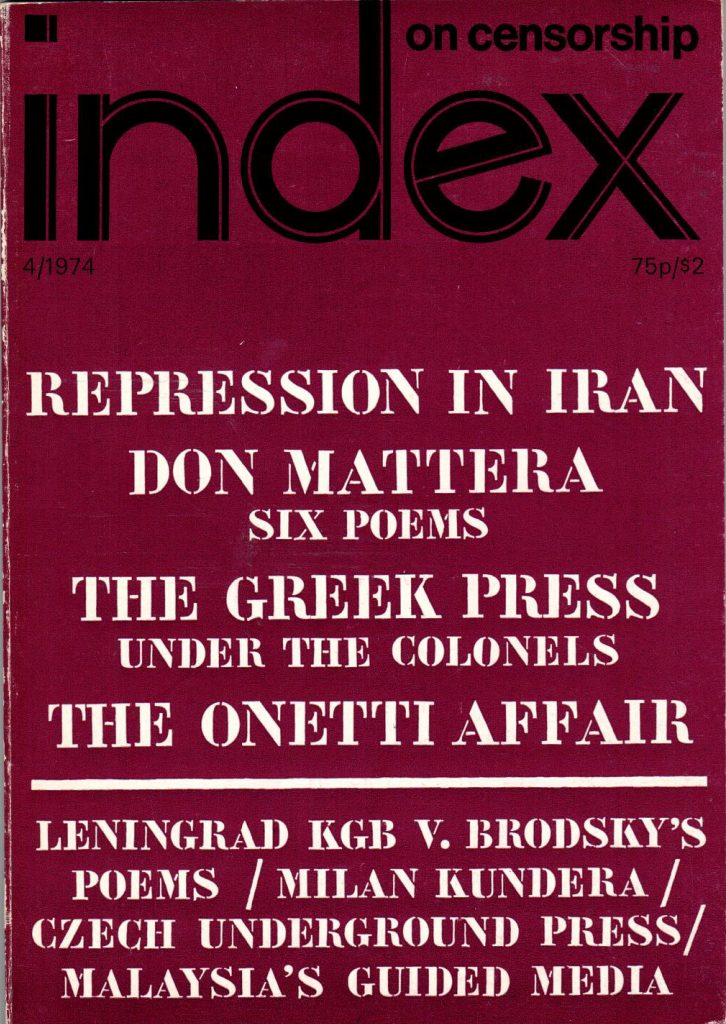

Repression in Iran , the Winter 1974 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Repression in Iran

Ahmad Faroughy

December 1974, vol. 3, issue 4

In October 1972, the shah of Iran celebrated the 2,500th year of Persian Monarchy which, despite twenty national dynastic changes, has constantly endeavoured to remain Absolute. Although the aim of this article is not to debate the political merits and demerits of autocracy as a means of government, it is obvious that whatever minor benefits Iran may have derived from hereditary dictatorship, freedom of expression is certainly not one of them.

Read the full article

China: Unofficial texts, the September 1979 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

The press since the shah

M. Siamand

September 1979, vol. 8, issue 5

The Muslim clerical establishment had not been decimated, and the various peoples of Iran, showing a remarkable unanimity, rallied behind the exiled Ayatollah to overwhelm the imperial army into submission by staring it In the face. What the great majority of observers regarded as impossible has come to be: the minority cultures seem no longer in danger of quick extinction, and everyone is engaged in an exhilarating debate about the future. But unfortunately, threatening clouds can be seen gathering on the horizon. The revolution has not yet started to devour its own children, yet some powerful men in the new hierarchy are already saying that it might have to do so: secular, democratic opponents of the former regime are denounced as counter-revolutionaries, most clergymen seem determined to turn Iran into an intolerant theocracy and a cultural backwater, and martyrdom for Islam is held up for the young as the highest achievement they should aim at.

Read the full article

The rebirth of Chilean cinema in exile, the April 1980 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Explaining Iran

Edward Mortimer

April 1980, vol. 9, issue 2

An extraordinary exhilaration gripped the Iranian people as the revolution at last triumphed and the remnants of the imperial regime suddenly crumbled away. One returns to confront the irritation of a European intelligentsia which is at once alarmed by the possible consequences of the Iranian revolution and perplexed by the fact that it does not quite fit into any of the ideological pigeon-holes which Western thought had prepared for it; and one is expected to atone by taking responsibility for the events which follow it.

Read the full article

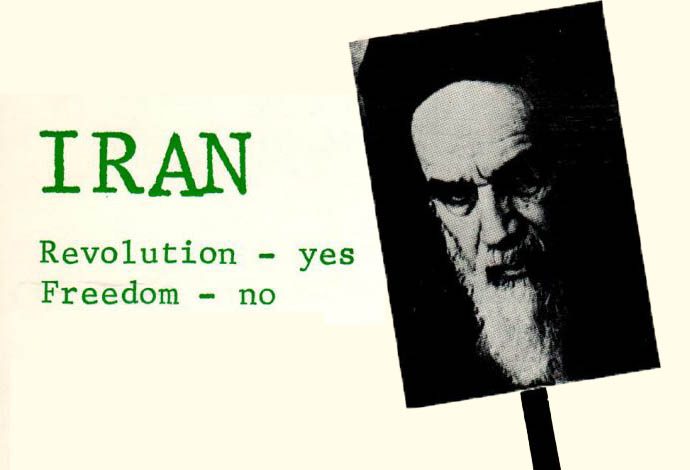

Iran: Revolution – yes, Freedom – no, the June 1981 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Iran since the shah

Leila Saeed

June 1981, vol. 10, issue 3

Concern for the restoration of social justice, for basic human rights, as well as national independence, provided the fundamental motive for the formidable mass movement which brought down the Pahlavi dynasty in February 1979. Iranians of different social backgrounds, ethnic and religious groups, of different creeds and ideologies came together in their revolt against the oppressive and arbitrary regime. And it was religion which provided the formal channels and the leadership by means of which the opposition expressed its demands and conducted its struggle.

Read the full article

Writers and Apartheid, the June 1983 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Islamic attack on Iranian culture

Amir Taheri

June 1983, vol. 12, issue 3

Book-burning did not become an Islamic tradition. On the contrary. The Bedouin’s enchantment in front of the written word soon prevailed over the Caliph’s ‘ impulsive outburst. Islam expanded and developed into an established religion with universal appeal, and became an accidental heir to the wisdom of the classical world which it later passed on to the West. In 1979, in the triumph of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, an echo of Omar was heard. In their hatred of the “corrupt” contemporary world, Iran’s mullahs, who had designed and led the revolution, tried to “return to the source” and recreate the early Islamic society as they imagined it. An important step in that direction was what the revolution’s Supreme Guide, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, described as “deculturisation”.

Read the full article

Samuel Beckett: Catastrophe, the January 1984 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Iran under the Party of God

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

February 1984, vol. 13, issue 1

Censorship was planned by the regime of the Islamic Republic even before the February 1979 revolution brought Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic oligarchy to power. This particular kind of censorship may not be without precedent in history, but it must certainly be rare. There were attacks on coffee-houses, restaurants and other public places by men armed with clubs and stones; unveiled women were harassed; slogans of the opposition were cleaned from the walls; banks, cinemas and theatres were burned. None of this seemed to follow any specific plan, but nonetheless it just kept on happening. Men with angry faces, dressed in shabby clothes, would be seen lurking in corners; they would come out for a moment of sudden violence and then disappear again. An astute observer might have called those attacks wounds on the body of the revolution as it was in the process of taking shape, but not many people noticed, and consequently they saw this deranged behaviour simply as a sign of revolutionary anger and class hatred.

Read the full article

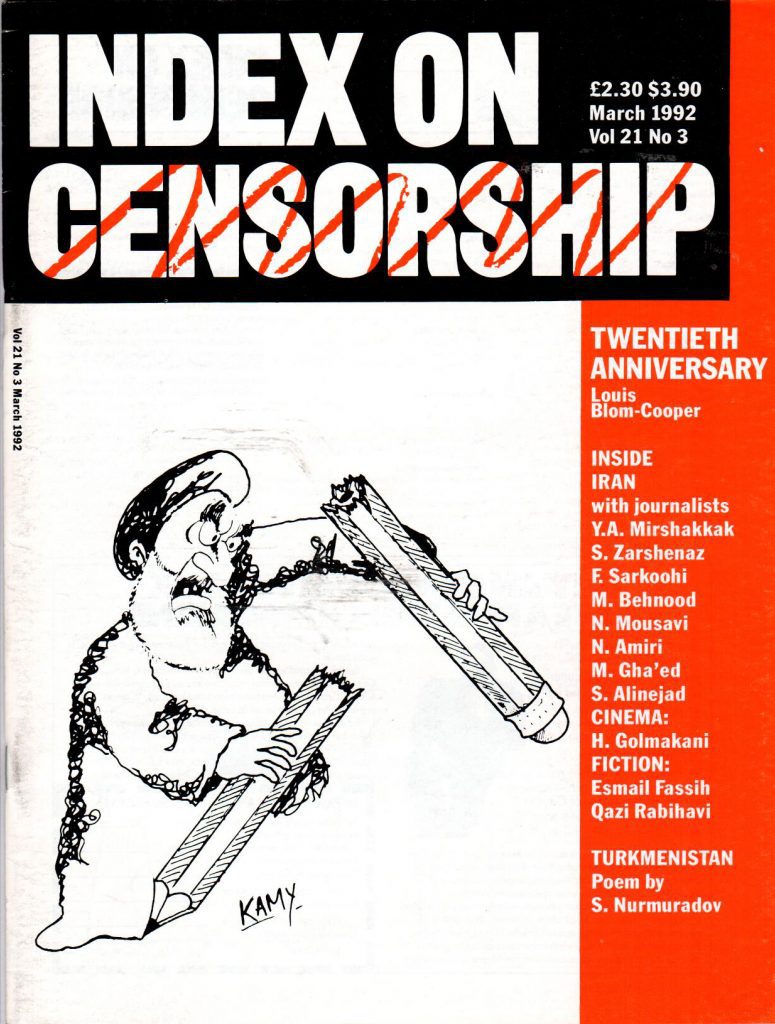

20th Anniversary: Freedom and responsibility, the March 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Inside Iran: A Special Survey

Gholam Hoseyn Sa’edi

March 1992, vol. 21, issue 3

Index brings together opposing views on the nature of human rights, freedom of expression and democracy within the Islamic Republic of Iran. This unique confrontation, first presented on 14 December 1991 on the UK’s independent Channel 4 TV programme South, reveals the gulf that separates the ‘universal’ principles of the Western Christian/humanist tradition from the theocentric teachings of Islam on the same matters. Even within Iran, the battle between rival and opposing interpretations of Koranic teaching on these subjects reaches into the highest levels of government.

As the Iranian journalist Enayat Azadeh, intimately connected with the film, himself says, we are not talking about anything as simple as those who are for and those who are against the Revolution. Committed supporters of the Islamic state who, influenced by education and inclination, wish to incorporate Western liberal ideas into Islamic thinking on, for instance, freedom of expression in the media or the arts, find themselves at odds with the pure Islamists who will brook no interference with the integrity of Islam

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1549892591542-afaf5ec8-5514-0″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jul 2018 | Global Journalist, Iran, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In 2009, incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s highly contested election against Mir-Hossein Mousavi, which led to public outrage and the formation of the Green Movement, filling the streets with demonstrations calling for Ahmadinejad’s ouster. For the next two years, Iranian authorities ran a campaign of jailing journalists and political opponents. Journalist Omid Rezaee was one such detainee.

The Iranian-born mechanical engineering student was the editor-in-chief of Fanous, a student magazine which was banned for standing with the Green Movement. Rezaee was arrested in October 2011.

In 2012 he fled to Iraq, and in 2015 he made his way to Germany. In February 2017 he started his own multilingual website, Perspective Iran, where news about Iran is mainly reported in German. He has also been working as a freelance writer within German media outlets since he was exiled. Rezaee aims to show the many hidden aspects of Iran and the nature of the everyday lives of its people.

Index on Censorship: You became a journalist at a very young age. What made you choose this career path so early?

Omid Rezaee: Storytelling excites me and has done so since childhood. It’s the first thing I learned about myself. First by reading stories – whether journalistic and media stories or fiction – and then by telling stories. When I was 10, I founded a small magazine in the primary school which failed after only two editions. By 15, I founded the second one in the first year of high school. This one was published for one year and by 17 I founded the next one which was being distributed in all high schools of our town and which brought me to the attention of the authorities for the first time. But I still think this was worth all the troubles because it gave me the opportunity to narrate stories. It’s the most delightful thing in this world.

Index: Why did you leave Iran?

Omid: The idea of leaving the country popped in my mind while I was sitting alone in a cell for days and nights without being able to see or talk to anyone. I was asking myself for how much longer I can bear this situation. When I was sentenced to two years in prison, I had to think about it more seriously. There are many reasons – both private and political – which led to my decision to leave the country. I would say the most important one – which still applies – is that I missed my freedom. First and foremost the freedom of speech, but it’s also freedom of lifestyle.

Index: Walk us through your migration on foot to Iraq.

Omid: Apart from the dangers and physical and technical things, I would never ever forget the moment I crossed the border as if it was the end of the earth. I would never forget how I looked back to the soil, the ground which used to be my homeland. I guess there is a huge difference when you leave the country by a plane and don’t see that “border”. And when you cross it on foot and you know, you won’t be back soon. This grieves you deeply.

Index: You are an active writer online. How do you think the internet has changed journalism?

Omid: I’ve started a professional career online and I am now studying digital journalism. By now it’s part of me and I’m part of the digital world. Honestly, I have no clue how the professional journalism used to work before it was online. But the fact that I can still report on Iran and the Middle East, even though I’ve been away for years, is directly due to the internet and online world. Apart from all the troubles we’re facing, we are closer to each other because of the internet. And more important: the digital world gives us – the journalists – more possibilities to strive against illegitimate authorities all over the world.

Index: How have you settled into life away from home?

Omid: It’s not true if I say I don’t miss my hometown, the city I studied in and the people I loved – or still love – and who love me. But the bottom line is that home is where one is free, where one can develop himself and live with dignity. I have a lot of good memories of Iran and I deeply miss a lot of people there, but I never considered Iran as a home, and it’s the same here in Germany. My home is my language. I don’t mean Farsi; I love German just as much my mother tongue, and this applies to the English language and the languages I’m learning right now. My home is the story I’m telling and I’m settling into my new life by telling stories. I am firmly convinced that only storytelling can rescue us.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]