Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

(Image: Oscar Mota/YouTube)

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

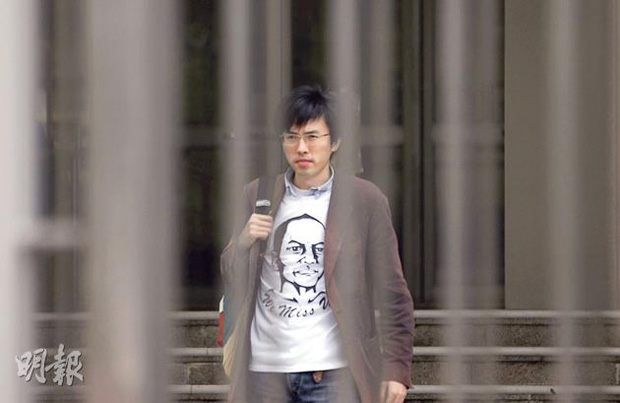

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Mouad Belghouat is a Moroccan rapper and human rights activist who releases music under the moniker El Haqed, roughly translated as The Enraged. His music has publicised widespread poverty and endemic government corruption in Morocco since 2011, when his song Stop the Silence galvanised Moroccans to protest against their government. He has been imprisoned on spurious charges three times in as many years, most recently for four months in 2014.

“I have not been able to find stable work since my first sentence, so I have concentrated on music – slam and rap. I brought out an album after my

second stretch in prison and this is what led to my second conviction”, El Haqed told Index on Censorship via email.

El Haqed’s 2014 album Walou — which is banned from being sold or played in public–translates as Nothing. Nothing, he clarifies in his songs, has changed in Morocco despite promises from King Mohammed VI and the government following mass protests, starting in February 2011. The 20 February Movement, which inspired tens of thousands of Moroccans across the country to march for constitutional change, protested against the country’s lack of civil liberties and rights, high illiteracy rates, huge rich-poor divide, insufficient healthcare and illegitimate election process.

“In 2011, I found myself at the heart of the 20 February youth movement, which caused me to question a lot of things – notably poverty, power, humiliation, inequality and freedom. I reflected these things in my writing and raps, and this quickly annoyed the regime,” El Haqed wrote.

After this demonstration of widespread dissent, Mohammed VI promised a comprehensive overhaul of Morocco’s undemocratic regime. He introduced a new constitution that pledged to better safeguard Moroccans’ human rights. But despite the fanfare, the plight of El Haqed and many others in the same situation suggest that the much-touted progress has been surface-deep.

After El Haqed’s most recent arrest outside a football stadium in Casablanca, he was charged with scalping tickets, public drunkenness and assault of a police officer. He denies the allegations, and believes instead that police had been looking for an opportunity to arrest him after the release of Walou — one officer at the scene was heard to say “I have scores to settle with you”. El Haqed and his brother were beaten by police as they were detained. El Haqed has said that police tortured him during later interrogation.

During his trial, witnesses of El Haqed being assaulted by police during his arrest were not allowed to give their testimony, and key pieces of evidence were rejected by the court without reason. His lawyers withdrew in protest. During his four-month imprisonment, he continued to write music and give impromtpu performances. When guards realised that his new songs were being published outside the prison, they confiscated his lyrics and put him in solitary confinement. He went on hunger strike to protest his treatment.

El Haqed continues to record and release music — just as he did after being arrested and imprisoned in 2011 and 2012, both times on dubious grounds. In the latter case, he was sentenced to a year in prison for “insulting the police”. His song Dogs of the State, which criticised the Moroccan police, was anonymously set to a YouTube video depicting a police officer with a donkey-head. El Haqed denied any involvement.

With three convictions in three years, El Haqed faces difficulties in pursuing his recording career because studios do not want to work with him because they fear government surveillance. He is banned from performing in public and lives with the knowledge that every action is being watched.

“I was profoundly touched by my nomination as a defender of free expression. Especially as now, and after three successive periods of incarceration, it is still hard to live”, El Haqed wrote.

El Haqed hopes to create a recording studio that will be open to all Moroccans and is currently working on a new album.

This article was posted on 25 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

The Moroccan rapper Mouad Belghaoute – also known as Lhaqed or El Haqed, ‘the enraged one’ – was sentenced on 1 July 2014 to four months in prison amid concerns that the trial was unfair, and that he is being held because of his popularity and lyrics that condemn corruption and police brutality. Arrested on 18 May, the 26-year-old rapper is expected to remain in prison until mid-September.

In an Open Letter to the Moroccan Minister of Justice and Liberties El Mustapha Ramid, 11 organisations committed to the defence of the rights to freedom of expression, culture and the arts have condemned the four-month sentence served against Mouad Belghouate following a trial that fell short of international standards:

7 July 2014

Mr El Mustapha Ramid

Minister of Justice and Liberties

Ministère de la Justice et des libertés Place El Mamounia – BP 1015

Rabat

Morocco

Fax: +212 537 73 47 25

We the undersigned organisations committed to the defence of the rights to freedom of expression, culture and the arts, condemn the four-month sentence served against musician Mouad Belghouate (aka El Haqed) following a trial that fell short of international standards. We are concerned that the sentence has been given in retribution for his involvement in Morocco’s pro-democracy movement, and specifically his condemnation of corruption and police violence through his music.

Convicted of assaulting police officers during an incident in Casablanca on 18 May 2014, evidence including testimonies of witnesses to the incident were not accepted by the court. This led defence lawyers to withdraw from the proceedings calling them “unjust” and “unfair”.

This is the third incident since 2011 where Belghouate has been imprisoned following trials that have been condemned as highly flawed. Notably in May 2012 he was imprisoned for 12 months for insulting police in a song and its accompanying video, a charge that clearly violated his rights to freedom of expression.

Belghouate has been closely engaged with the 20th February democracy movement, and he has been openly critical of corruption in Morocco and accused police of brutality in his lyrics, leading to concerns that these are the source of the accusations against him, concerns that are heightened by trial irregularities.

Morocco has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which includes the rights to freedom of expression and fair trial. We therefore call on the Moroccan authorities to immediately release Mouad Belghouate and to ensure that any appeal be carried out fairly and include all evidence and witnesses relevant to the case.

Yours sincerely,

Arterial Network

ARTICLE 19

European Composer and Songwriter Alliance

European Council of Artists

freeDimensional

Freemuse

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression, Turkey

Equity’s International Committee for Artists’ Freedom (ICAF)

Observatoire de la liberté de creation, France

Vivarta

Copies to:

President of National Human Rights Council Mr. Driss El Yazmi

Minister of Culture, Mr Mohamed Amine Sbihi

Association Marocaine des Droits Humains (AMDH), Mr. Ahmed El Haij (President)

» Arabic: المغرب: رسالة مفتوحة إلى وزير

Despite promising reform and introducing a new constitution in 2011, Morocco’s treatment of dissidents indicates the changes were just window dressing, Samia Errazzouki writes

Morocco’s King Mohammed VI announced a constitutional reform process during a 9 March 2011 speech, following popular protests organised by the 20 February Movement. Regime supporters and allies — France and the United States — hailed the move towards reform as “unprecedented.” Morocco was soon referred to as the “model for the region.”

But the government’s repression of freedom of expression has remained steadfast even after the new constitution.

Most recently, in March 2013 dissident rapperMouad Belghouat (alias El Haqed) was released from jail after he served his second, year-long prison sentence over his anti-regime lyrics, which were described as “undermining state authority.”

In February 2012, 18-year old Walid Bahomane was charged with “defaming Morocco’s sacred values” after he posted a caricature of Mohammed VI on Facebook. Even though he did not create the illustration, Bahomane was convicted and sentenced to one year in prison for the act of sharing the image.

In February 2012, 18-year old Walid Bahomane was charged with “defaming Morocco’s sacred values” after he posted a caricature of Mohammed VI on Facebook. Even though he did not create the illustration, Bahomane was convicted and sentenced to one year in prison for the act of sharing the image.

In the same month, Abdessamad Hidour, an activist with the 20 February Movement faced similar charges after a video of him criticising Mohammed VI was uploaded on Youtube. In the video, he likened Mohammed VI’s reign to colonialism and railed against his corrupt practices, landing him a three-year prison sentence.

These are only a few cases out of many that have drawn widespread attention over the nature of the charges as well as the expedited trials that landed all those charged in jail.

Morocco’s latest constitution supposedly grants the right to freedom of expression, but it still leaves room for repression.

The king stacked the constitutional reform deck by appointing the committee to undertake the work. The reforms introduced some liberalisation, but did not address demands for democratisation of the system. It’s an old trick dating to the 1960s when Morocco’s first constitution was drafted following its independence from France.

The latest version of the constitution incorporates human rights language and places greater attention on the legal protection of free speech, such as the following:

Out of context, these articles stand as testaments for what regime supporters describe as “landmark reforms.” However in scrutiny and in practice, these articles have proved to be futile. In Article 28, for example, immediately after stipulating the guarantee of freedom of the press, there is a caveat that leaves this article open to interpretation: “All have the right to express and to disseminate freely and within the sole limits expressly provided by the law, information, ideas, and opinion.” Immediately, “freedom of the press” is limited to a legal framework dictated by the regime and this interpretation has come into play in various recent trials where freedom of speech and press has been threatened, especially in instances when the monarchy has been the target of criticism.

The regime’s response to free speech cases following constitutional reform is swift and relatively consistent, indicating no clear break from its past policies. Despite these violations of freedom of expression, Moroccans continue to express their dissent in multiple media, from online publications to protests on the streets, indicating that the regime’s alleged “path toward reforming” is long and winding.

Samia Errazzouki is a Moroccan-American writer and co-editor of Jadaliyya’s Maghreb Page.