Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

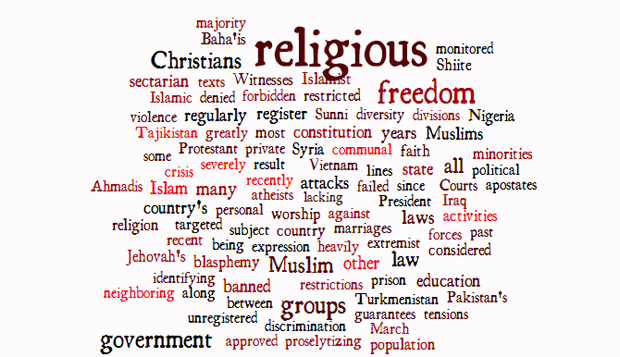

In January, Index summarised the U.S. State Department’s “Countries of Particular Concern” — those that severely violate religious freedom rights within their borders. This list has remained static since 2006 and includes Burma, China, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan. These countries not only suppress religious expression, they systematically torture and detain people who cross political and social red lines around faith.

Today the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent watchdog panel created by Congress to review international religious freedom conditions, released its 15th annual report recommending that the State Department double its list of worst offenders to include Egypt, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam and Syria.

Here’s a roundup of the systematic, ongoing and egregious religious freedom violations unfolding in each.

1. Egypt

The promise of religious freedom that came with a revised constitution and ousted Islamist president last year has yet to transpire. An increasing number of dissident Sunnis, Coptic Christians, Shiite Muslims, atheists and other religious minorities are being arrested for “ridiculing or insulting heavenly religions or inciting sectarian strife” under the country’s blasphemy law. Attacks against these groups are seldom investigated. Freedom of belief is theoretically “absolute” in the new constitution approved in January, but only for Muslims, Christians and Jews. Baha’is are considered apostates, denied state identity cards and banned from engaging in public religious activities, as are Jehovah’s Witnesses. Egyptian courts sentenced 529 Islamist supporters to death in March and another 683 in April, though most of the March sentences have been commuted to life in prison. Courts also recently upheld the five-year prison sentence of writer Karam Saber, who allegedly committed blasphemy in his work.

2. Iraq

Iraq’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but the government has largely failed to prevent religiously-motivated sectarian attacks. About two-thirds of Iraqi residents identify as Shiite and one-third as Sunni. Christians, Yezidis, Sabean-Mandaeans and other faith groups are dwindling as these minorities and atheists flee the country amid discrimination, persecution and fear. Baha’is, long considered apostates, are banned, as are followers of Wahhabism. Sunni-Shia tensions have been exacerbated recently by the crisis in neighboring Syria and extremist attacks against religious pilgrims on religious holidays. A proposed personal status law favoring Shiism is expected to deepen divisions if passed and has been heavily criticized for allowing girls to marry as young as nine.

3. Nigeria

Nigeria is roughly divided north-south between Islam and Christianity with a sprinkling of indigenous faiths throughout. Sectarian tensions along these geographic lines are further complicated by ethnic, political and economic divisions. Laws in Nigeria protect religious freedom, but rule of law is severely lacking. As a result, the government has failed to stop Islamist group Boko Haram from terrorizing and methodically slaughtering Christians and Muslim critics. An estimated 16,000 people have been killed and many houses of worship destroyed in the past 15 years as a result of violence between Christians and Muslims. The vast majority of these crimes have gone unpunished. Christians in Muslim-majority northern states regularly complain of discrimination in the spheres of education, employment, land ownership and media.

4. Pakistan

Pakistan’s record on religious freedom is dismal. Harsh anti-blasphemy laws are regularly evoked to settle personal and communal scores. Although no one has been executed for blasphemy in the past 25 years, dozens charged with the crime have fallen victim to vigilantism with impunity. Violent extremists from among Pakistan’s Taliban and Sunni Muslim majority regularly target the country’s many religious minorities, which include Shiites, Sufis, Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Baha’is. Ahmadis are considered heretics and are prevented from identifying as Muslim, as the case of British Ahmadi Masud Ahmad made all too clear in recent months. Ahmadis are politically disenfranchised and Hindu marriages are not state-recognized. Laws must be consistent with Islam, the state religion, and freedom of expression is constitutionally “subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam,” fostering a culture of self-censorship.

5. Tajikistan

Religious freedom has rapidly deteriorated since Tajikistan’s 2009 religion law severely curtailed free exercise. Muslims, who represent 90 percent of the population, are heavily monitored and restricted in terms of education, dress, pilgrimage participation, imam selection and sermon content. All religious groups must register with the government. Proselytizing and private religious education are forbidden, minors are banned from participating in most religious activities and Muslim women face many restrictions on communal worship. Jehovah’s Witnesses have been banned from the country since 2007 for their conscientious objection to military service, as have several other religious groups. Hundreds of unregistered mosques have been closed in recent years, and “inappropriate” religious texts are regularly confiscated.

6. Turkmenistan

The religious freedom situation in Turkmenistan is similar to that of Tajikistan but worse due to the country’s extraordinary political isolation and government repression. Turkmenistan’s constitution guarantees religious freedom, but many laws, most notably the 2003 religion law, contradict these provisions. All religious organizations must register with the government and remain subject to raids and harassment even if approved. Shiite Muslim groups, Protestant groups and Jehovah’s Witnesses have all had their registration applications denied in recent years. Private worship is forbidden and foreign travel for pilgrimages and religious education are greatly restricted. The government hires and fires clergy, censors religious texts, and fines and imprisons believers for their convictions.

7. Vietnam

Vietnam’s government uses vague national security laws to suppress religious freedom and freedom of expression as a means of maintaining its authority and control. A 2005 decree warns that “abuse” of religious freedom “to undermine the country’s peace, independence, and unity” is illegal and that religious activities must not “negatively affect the cultural traditions of the nation.” Religious diversity is high in Vietnam, with half the population claiming some form of Buddhism and the rest identifying as Catholic, Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, Protestant, Muslim or with other small faith and non-religious communities. Religious groups that register with the government are allowed to grow but are closely monitored by specialized police forces, who employ violence and intimidation to repress unregistered groups.

8. Syria

The ongoing Syrian crisis is now being fought along sectarian lines, greatly diminishing religious freedom in the country. President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, aligned with Hezbollah and Shabiha, have targeted Syria’s majority-Sunni Muslim population with religiously-divisive rhetoric and attacks. Extremist groups on the other side, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), have targeted Christians and Alawites in their fight for an Islamic state devoid of religious tolerance or diversity. Many Syrians choose their allegiances based on their families’ faith in order to survive. It’s important to note that all human rights, not just religious freedom, are suffering in Syria and in neighboring refugee camps. In quieter times, proselytizing, conversion from Islam and some interfaith marriages are restricted, and all religious groups must officially register with the government.

This article was originally posted on April 30, 2014 at Religion News Service

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

As states have been revealed to be snooping on citizens and other governments, and we are confronted by data breaches and security issues like the latest Heartbleed crisis, more people are becoming aware of their internet rights. Voters and civil society around the world are pushing their governments to provide secure and private online spaces for internet users. It is quite refreshing to see Pakistan’s government working for internet laws. However, though some provisions of the proposed Computer Crimes Law (CCL) are copied from other countries’ legislation, several parts of the draft version violate international human rights, including the freedom of expression.

In an attempt to offer support to the government of Pakistan, Article 19 and Digital Rights Foundation Pakistan dissected the draft legislation to point out the provisions that need to be amended, and to help the government conform to international human rights norms. It is mandatory at this point to pressure the government to put in place better internet legislation in order to avoid future misuse of the legal framework, as has happened with other laws.

A leading example of how such poorly devised laws help authorities abuse power is the Monitoring and Reconciliation of International Telephone Traffic Regulations (MRITT), also known as the Grey Traffic legislation. Passed in 2010 to help the government ban anonymous communication and VPN usage, MRITT mandates the monitoring and blocking of any encrypted and unencrypted traffic that originates or terminates in Pakistan, including phone calls and data.

MRITT legitimised blocking and internet monitoring on a massive scale — allowing a ban on VPN and VoIP services like Skype, Viber, WhatsApp and SpotFlux among others. The implementation of this legislation raises several concerns especially among the business community of Pakistan. The first official notification citing the MRITT to block VPN was issued in July 2011, targeting “all mechanisms which conceal communication to the extent that prohibits monitoring”.

The global reliance on the internet for communications and the, at times, complete blackouts of certain services by the government of Pakistan pose serious economic challenges. Not only business, but educational activities are hampered by the implications of MRITT. It also affects the privacy rights of Pakistani citizens. License deploying monitoring systems are expected to provide data — including a complete list of Pakistani consumers and their details — to the authorities when required under sub clause 6(d) of Part II of the regulation.

The Pakistan Protection Amendment Bill 2014 is another scary example of a woolly worded law. It was recently passed by Pakistan’s national assembly and is awaiting approval by the senate. Human Rights Watch stated that: “The vague definition of terrorist acts, which could be used to prosecute a very wide range of conduct — far beyond the limits of what can reasonably be considered terrorist activity. Besides ‘killing, kidnapping, extortion,’ the law classifies highly ambiguous acts including ‘Internet offences’ and ‘disrupting mass transport systems,’ as prosecutable crimes without providing specific definitions for such offences.”

The latest version of the Computer Crimes Law has been drafted by the Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunications (MoITT). The proposed law establishes various computer crimes and sets out rules for investigation, prosecution and trial of these offences. Acts such as illegal access to and interference with programs, data or information systems; cyber terrorism; electronic forgery and fraud; making of devices for use in these types of offences; and unauthorised interception of communication are included. Like MRITT, it is feared that the Computer Crimes Law in its current draft form, if passed, would include several violations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Pakistan acceded in 2010.

The concerns over the Computer Crimes legislation mentioned by Article 19 and Digital Rights Foundation, include lack of proper definitions of terms like content, data, information system or program. Their recommendations also highlight concerns about broader cyber-terrorism offences under Section 7 (a) and (b), and more importantly, the lack of procedural safeguards against unchecked surveillance activities carried out by the country’s intelligence agencies.

At this stage of the process, it is important for regional and international civil society and internet privacy rights groups to put pressure on the government of Pakistan to make the right amendments to the law before passing it. This law is extremely important for providing safety and security to Pakistani internet users and cannot be abolished or delayed. It is only right, then, that it introduces correct and clearly defined provisions to make it effective, and not vulnerable to abuse by authorities.

This article was published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

In the sixth attack on Express Media employees unknown assailants threw a hand grenade at the gate of Express News bureau chief’s house in Peshawar’s Murshidabad area. Though no one was injured in Sunday’s incident, it highlights the dangers for Pakistan’s journalists.

“It was 6:30 am. I woke up to a loud screeching made by a motorbike, followed seconds later by a thunderous sound. I ran out and saw a cloud of smoke,” said 38-year old Jamshed Baghwan, speaking to Index over phone from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s provincial capital, Peshawar.

The main gate and the walls of neighbouring houses, said the journalist, were pocked with holes made by ball bearings packed in bomb.

This was the second attack on Baghwan. On March 19, he had found a 2 kg bomb “at exactly the same place” which was diffused in time by the bomb disposal unit.

“I have no idea why anyone would attack me,” he said. “I’ve covered the army operation in Swat when the security forces cleansed the place of militants; I’ve covered conflicts in Bajaur and South Waziristan, but there never was a threat from any quarter, so why now?” he is perplexed.

This is the sixth attack on Express Media organisation in the last nine months. Four of Express’s employees have been killed.

On March 28, a senior Pakistani analyst, Raza Rumi, working for Express News, came under a volley of gunshots after his car was intercepted by gunmen on motorbikes, while passing a busy market place in Lahore. He has been vocal in his condemnation of the Taliban and religious extremist groups. While Rumi narrowly escaped, his driver died and his guard remains critically injured.

An editorial, by Express Tribune, a sister organisation, had frustration and helplessness written all over when it read: “Shall we just close shop, keeping in mind that we are no longer safe telling the truth and the state clearly cannot, or may not want to, provide us protection or even justice?”

The same day as the attack on Baghwan, in the eastern city of Lahore, in the Punjab province, a rally was held by journalists and civil society to protest the death threats on Imtiaz Alam, secretary general of South Asia Free Media Association.

Political leaders and the government routinely condemn attacks on media workers, but have yet to take concrete action. In the meantime, journalists continue to die. Declan Walsh of the New York Times tweeted: “When militants take on journalists, this is how it goes – one by one, they pick them off. Outrage is not enough.”

With no let up in the attacks, journalists are saying they need to watch their own as well as their colleagues’ backs.

But is it possible when journalists have yet to come together?

Kamal Siddiqi, editor the Express Tribune lamented: “…there is no unity amongst the journalist community. We have a great tradition of abiding by democratic traditions but at the same time we have done poorly in terms of sticking together. There are splinters within splinters,” he wrote in his paper.

However, media analyst Adnan Rehmat, finds solidarity and sympathy for those who have been attacked or are under threat among the journalists. “It’s the media owners who are not forthcoming. The pattern and nature of attacks is consistent; but not the response from media owners,” he says.

He recently published a book titled Reporting Under Threat. It is an “intimate look into the harsh every-day life of journalists working in hostile conditions” through testimonies from 57 Pakistani journalists, including editors, reporters, camerapersons, sub-editors, news directors, photographers, correspondents and stringers working for TV channels, newspapers, radio stations and magazines.

“They don’t consider the attack on one individual an attack on all,” he points out. “While Rumi’s attack elicited a strong reaction from civil society, there was little condemnation from media houses. On the other hand, because Alam does not work for any competing newspaper or channel, it was easier to support him and this was across the board.” Part of the problem, said Rehmat was the media owners were not journalists and therefore did not equate themselves with journalists.

Rehmat believes, it is time, the media owners gathered on platforms like the All Pakistan Newspapers Society, Pakistan Broadcaster’s Association (representing private TV channels) and the Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors and come up with a “singular response” in the form of policies that reflect that “safety of journalists is their number one priority”.

“I think the media owners are playing into the hands of the militants,” pointed out Shamsul Islam Naz, former secretary general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists. “If this is a dangerous business, why hasn’t a single media owner been killed yet?” He said he had been observing the way private news channels had been covering militancy and giving unsolicited air time to banned militant outfits infraction of Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority.

Ironically, these attacks follow a high level meeting of Committee to Protect Journalists delegation with prime minister Nawaz Sharif in which the latter had pledged to address the threats to country’s journalists. Among the several commitments, was putting protection of journalists on the agenda in the ongoing peace talks with the Taliban.

According to CPJ, since 1992, 54 journalists have been killed with their motives confirmed, meaning CPJ is reasonably certain that the journalist was killed in line of duty.

While militants openly admit to the attacks, this is not the only threat to journalists. There are state elements including its intelligence agencies, members of elected political parties, even those from the business community, who may go from simply roughing up, torturing, detaining, to even killing if the dissenting voices get relentless and refuse to keep quiet.

This article was posted on 9 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Shapoorjee Sorabjee, the first historian of cricket in India, had cautioned more than a century ago in 1897- “… to expect all political difference to disappear or all available self-interests to be foregone on the institution of cricket relations is to live in a fool’s paradise.” Sorabjee’s words echo loudly in the persecution of 67 Kashmiri Muslim students in the city of Meerut on March 6. Historian Ramachandra Guha’s statement- “post-independence, cricket was equated with patriotic virtue”, echoes louder.

These local college students had cheered the Pakistan cricket team which trounced India in a cricket tournament. In normal circumstances, cheering a team would not have been considered perfidious or criminal. Unless of course one is thrown back to 1945, when Orwell acerbically noted that there’s nothing like certain spectator sports to add to the fund of ill-will between nations and their populations. Or, more recently, to the times of Norman Tebbit and David Blunkett for whom a cricket match was the perfect crucible to test one’s loyalty to his country.

But Indo-Pak cricket matches are anything but “normal”. On the Indian side of the border, they are nothing but battles to be won, and once victory has been achieved, to be celebrated by humiliating, vilifying and demonising “the other”, that is, Muslims. And when there are Kashmiri Muslims, the viciousness is increased manifold.

So it happened that these students were charged with sedition, which under Indian criminal law, is equivalent to treason, and carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which in its present incarnation can give the British National Party and United Kingdom Independence Party lessons in jingoism and xenophobia, quickly bared its fangs, and raised a din about bringing these “terrorist” students to justice. Not unsurprising, when its senior leader and a proclaimed patron of cricket, states with pride that cricketing nationalism is an integral aspect of a person’s national identity. When the charges were withdrawn following a loud backlash, the BJP rushed to the election commission alleging that the ruling party in Uttar Pradesh (where Meerut is located) was violating the poll code by this act of pandering to anti-national Muslims.

This sordid affair brings back memories of March 2003. The police top brass in Calcutta had planned how to prevent Muslims from supporting Pakistan during the World Cup quarter-final against India. When India won, a precedent of sorts was set- the army chief, the prime minister and deputy prime minister rang up the players and congratulated them. Such praise is usually reserved for occasions when the team wins the tournament, and not a particular match. In Ahmedabad, riots broke out when Muslims were prevented from celebrating India’s win.

It is easy to excoriate the Hindu right wing parties, but rabid Islamophobia is par for the course in so far as they are concerned. The Meerut incident demonstrates a new use of sedition initiated not by the usual suspects but by a state government which professes to be secular.

An incident of 2010 brings out the novelty factor. Arundhati Roy had criticised the government for decades of brazen civil rights violations in Kashmir, and demanded that the people of the disputed territory be allowed to exercise their right of self-determination. The “patriotic” Hindu right went ballistic, and demanded that she be tried for sedition and also deported. Charges were pressed, and even some sections of the media were complicit in an all-out attack against her, as this report details.

But Meerut is not the bastion of the rabid fundamentalists, so what could have happened? The answer is found in the antecedents of the college administrators who went to the police in the first place. The rector and chancellor are a retired police officer and army general, respectively. Representatives and agents of the Indian state, which has always used the sedition law to squelch dissent and perpetrate impunity. Almost like Omar Abdullah, the chief minister of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, who exposed his real stance by calling the charges harsh and unacceptable, and in the same breath, labelled the students’ actions as “wrong and misguided”. But more striking is the cynical opportunism by the government of Uttar Pradesh. It had done nothing to stop the bloody riots in Muzaffarnagar last year but beat the tin drum of it being “secular” to the core. Taking it one step further, it used a law described as “objectionable and obnoxious” by none less than India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to curry favour with the majority Hindu constituency on the eve of national elections.

Whoever thought that the odious doesn’t have its productive uses?

This article was posted on March 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org