Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Malala Yousafzai opened the Library of Birmingham in September. Her own book is now banned in Pakistani private schools. (Image Michael Scott/Demotix)

“My friend told me Malala is not a Pakistani or a Muslim; her real name is Jennifer and she is a Christian,” said ten-year old Fatemah, conspiratorially. “But I don’t believe her one bit,” she added waving the book “I am Malala”. She is reading the autobiography of Malala Yousafzai, the young Pakistani girl who survived an assassination attempt by the Taliban.

The rather precocious 10-year old went on to say the book “gave me something important to reflect on… That what I had always taken for granted, like education, does not come that easily for thousands.” She found Malala to be a “real hero” for standing up for what she believed in. Fatemah may just be ten but her views are reflective of the debate raging in Pakistan today, especially in the media, after the book surfaced and was subsequently banned in some private schools.

On 10 November, the All Pakistan Private Schools Federation (APPSF), announced the decision to ban the book from member schools for “being against the injunctions of Islam and the constitution of Pakistan”. The book will not be kept in the library of any of its schools and no co-curricular activities, including debates, will be held on it, Kashif Mirza, chairman of the APPSF told Index. Almost 25 million children, 10 million of which are girls, study at the federation’s 152,000 private school. They employ 7,250,000 teachers, 90 percent being women. The book has not officially been banned by the Pakistani government in state schools, but is not part of any school’s curriculum.

Yousafzai has been bagging one award after another internationally. In Pakistan, where the entire nation had rooted for her to win the Nobel Peace prize, the book has led to a slight dimming of that adulation. Having British award-winning journalist Christina Lamb’s name on the cover as co-author hasn’t helped. “Lamb is reputed to be both anti-Pakistan and anti-Islam,” Mirza said.

Dr AH Nayyar, a noted educationist, said the reaction of the private school owners was that of “weak-kneed people” who are more worried about their “business interests” than what “is right and what is wrong”.

Rumana Hussain, a former principal of a private school who has written and illustrated several children’s books, finds it tragic that “the 25 million students who attend private schools in the country will not read the book. The millions who attend public schools, where the book isn’t banned but won’t be taught, bought or stocked, will not read it either.”

She lamented: “All of them will be deprived of the chance to read the account of a young Pakistani girl’s struggle for education – not only for herself but also for every Pakistani girl, every child – and get inspiration from her story.”

“We are not against girls education or against Malala,” argued Mirza. “On the contrary, we are a great supporter of Malala’s mission of girl’s education and have always advocated for liberal, enlightened and empowered women. When Malala was shot, for the first time in the history of private schools, we held a strike and closed all schools.”

Today, however, Malala seems to have lost favour in the eyes of Mirza and many others who think like him.

“I have read the book and find it hard to believe that a child who of just 16 has so much knowledge of international affairs,” he said, implying that the west has used her “confused state of mind” to grind their own axe.

Dr Nayyar finds this argument hard to digest. “The book was written by a non-Muslim. How does her writing make Malala a tool in the hands of the west?”

But what exactly has Malala or Lamb written that has half of Pakistan in a tizzy?

“She has shown disrespect to Prophet Muhammad by not using Peace be Upon Him after his name. She speaks of [former Pakistani president] Zia ul Haq bringing the Islamic law of reducing the women’s evidence to half into the court. She can’t comment on that as it’s in the Quran and no more can be said about it. She also talks about her father referring to Satanic Verses and believing in freedom of expression. We can’t have young impressionable minds reading her, having her as her role model and going astray,” Mirza said adamantly.

What he failed to mention was that all this had happened during her father’s college days when he took part in a debate of whether Satanic Verses should be banned and burned. The Satanic Verses controversy, also known as the Rushdie Affair, was the heated and frequently violent reaction of some Muslims to the publication of Salman Rushdie’s novel, first published in the United Kingdom in 1988. While few Pakistanis may have read the novel, most have been led to believe that it is an insult to Islam because it disparaged the honour of the Prophet Muhammad.

Malala’s father, while finding the book offensive to Islam had the courage to suggest, to a packed room of fellow students: “First, let’s read the book and then why not respond with our own book.”

Nayyar found absolutely nothing wrong with what Malala has stated. “That minorities are often attacked in Pakistan and that Ahmedis regard themselves as Muslims while the government does not; every word of these statements is true. Even the quoted statement of her father about Rushdie’s book Satanic Verses is praise-worthy; face a blasphemic book with a good book of your own,” he said.

“I think the ban is condemnable even if it applies to a few thousand schools,” said Zohra Yusuf, chairperson of the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. “We should be opening up young minds, not shutting them. Malala’s story should be a great inspiration for students,” she added.

“I did not find anything objectionable in the book itself,” said Farah Zia, the editor of English daily The News’ magazine The News on Sunday section. “The only problem I had was the voice of the book, that switched between a 16 year old and a mature one,” added the mother of two.

While the ban has not been enacted across the board yet, she finds it ridiculous. Still, she hopes the controversy may make many curious enough to pick up the book and read it. On the other hand, she says the “atmosphere of fear being artificially created” may stop publishers from translating the book into local languages.

This article was originally posted on 15 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

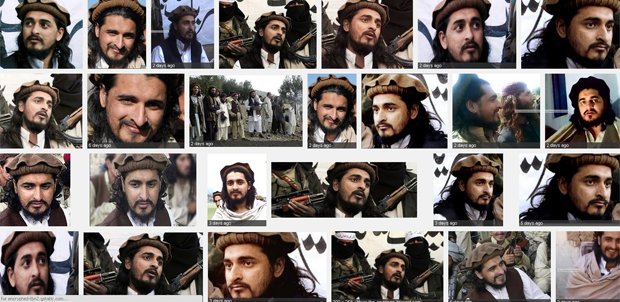

When Shamsheer Khan, learnt about the drone strike on Hakimullah Mehsud, the Pakistani Taliban supremo, on Nov 1, the 45-year old taxi-driver in Karachi, went to the mosque and prostrated before God to help the young fighter. “I prayed that if he were fighting a jihad against the Americans, Allah should protect him and if he had expired in way of jihad, to elevate him to the highest position of an Islamic fighter.”

Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike in the Dande Darpakhel, in the North Waziristan tribal region of Pakistan, bordering Afghanistan. He had succeeded Tehrik Taliban Pakistan’s (TTP) Baitullah Mehsud, in 2009, after the latter was killed in a similar attack by the drones.

Mehsud has claimed to have orchestrated several fatal attacks on the Pakistan army and also had a hand in the 2010 suicide attack in Afghanistan in which seven CIA agents were killed.

Strangely, Khan’s empathy for a perpetrator of violence finds resonance across the country where anger against drones is high, a reason for such an extreme anti-American sentiment.

Shortly after Mehsud’s death was confirmed, leaders from religious-political parties like the Jamaat-i-Islami’s (JI) Munawar Hasan called him a “martyr” and Jamiat Ulema-i Islam’s (JUI) Fazlur Rehman went a step further saying anyone killed by US is a martyr.

The taxi driver justified the violence saying: “When the leaders of this country have sold their souls to the West, somebody has to bring them back to the true path of Islam and if violence is what is needed, then be that.”

But Mosharaf Zaidi, a political analyst has no illusions that Mehsud is none other than a “mass murderer.” Calling Mehsud “a martyr was a grave tactical error and a dangerously immoral thing to do,” he said, adding. “The TTP is a terrorist organisation that deserves neither any sympathy from Pakistan, nor from any other country,” he added.

Zahid Hussain, defence analyst and author blames it on a “complete disarray” he sees in Pakistan’s policy. “Nawaz Sharif wants to normalize relations with the US, but there is no clarity on how he wants to deal with the issue of rising militancy in Pakistan that also threatens the US interests in the region.”

When news of Mehsud’s death reached the rulers, the narrative changed slightly. Though not directly empathising with the TTP, Pakistan’s interior minister, Chaudhry Nisar said the drone attack had scuttled the peace process that the government was about to start with the Taliban. Imran Khan, also in favour of talks with the Taliban, threatened stopping the NATO supply line going through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, where his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) is ruling, if drone strikes did not end.

“The TTP shura [council] had frequently derided the notion of peace talks and, even before the death of Mehsud, had not committed to negotiations,” pointed out said Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, noted peace activist and an academic.

Still, if negotiations have to happen, Zaidi said these “must begin with the organisation’s [TTP] acceptance of the Pakistani constitution and the sovereignty of the Pakistani republic over Pakistani territory.” He, however, was sceptical of saying “no sign of such an acceptance” seemed to exist.

To a nation, in the throes of daily violence, last week’s events have only led to historic bewilderment bordering on the dangerous. A wave of confusion seems to have enveloped the people blurring the distinction between a hero and a villain.

“It only confuses an already shattered national discourse in Pakistan about rule of law, national sovereignty and a bright future for Pakistani children,” said Zaidi.

Hoodbhoy finds Mehsud being termed a martyr incredulous. “It indicates some kind of collective mental disorder!” he said, adding: “The Pakistani mind, whipped into hyper anti-Americanism by the media and parties like PTI and JI, appears to have lost its sense of balance.”

To Zaidi, Pakistan’s handling of the TTP has been nothing short of tragic. He puts the blame squarely on both the government and political leaders who helped “create a narrative in which Mehsud, seems to have become a victim of drones.” He said the drone strikes would not exist if the Pakistani state had taken care of the criminals and terrorists that have been “festering and building up in FATA and beyond since well before 9/11”.

With the new TTP leader Mullah Fazlullah though, there is little doubt among the Pakistani people over who their foe and versus friend is. Fazlullah had virtually held the valley of Swat hostage and embarked on a systematic, violent movement to wipe out dissent back in 2007-2009. Last year it was his men who had shot Malala. Eventually the army had to step in and flush him and his followers out of the region.

To Hoodbhoy, this change of guard has given the Pakistani state a “narrow window of opportunity to hit Fazlullah and his band of terrorist thugs before he consolidates his power.”

But, he questioned: “Will we be able to find the courage and strategic wisdom? He answered it himself with a grim: “I doubt it!”

On 10 Nov, the Inter Services Public Relations, which is the official PR cell of the army, condemned the use of the word martyr to describe Mehsud, saying it misleading and irresponsible.

This article was originally published on 11 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

It’s been over two weeks now that Rana Tanveer, a reporter in Lahore at the English daily, Express Tribune, has not gone to work.

Early this month, he received a one-page letter, in the Urdu language, terming him an apostate and accusing him of writing in favour of Ahmadis and Christians.

“It warned me to stop writing ‘against’ Islam and seek ‘forgiveness’ from God,” he said over the phone from his home in the Punjab province.

It further warned him that if he did not desist, he would be killed — since that is the punishment of a person declared an apostate.

“I can’t work like this; no reporter can, if he cannot roam about freely,” said Tanveer.

Initially, he did not take the letter too seriously, but a week after he received the letter, he felt he was being followed on a motorbike. “It’s a scary experience,” he conceded, adding: “I made a few turns just to be sure that this was not a figment of my imagination, but the man on the motorbike persisted. I knew then that this was no joke and I had to do something.”

His seniors at work advised him to at least file a complaint with the police, which he did, but he did not name anyone “due to security reasons”.

“My editor told me to keep a low profile and not to report on minority issues for a while, and if I had to, it would go without by byline,” said the journalist.

Farahnaz Zahidi, features editor in the same paper as Tanveer’s feels very strongly about one’s byline being taken away. “As a journalist, perhaps the biggest satisfaction in this otherwise perilous and often under-paid profession is one’s by-line; it also lends credibility.”

However, she added, by shooting the messenger, society loses out. “The right to information is threatened when media persons threatened.”

Tanveer finds a plethora of minority rights abuses strewn around his city but says few journalists feel inclined to take up these issues.

“Mine seems to be a lone battle,” he said. “I am often scorned by my colleagues for reporting ‘chooras’ (derogatory term used for Christians, also among the poorest sections of society and consigned to menial janitorial jobs) and ‘Qadianis’ (also a derogatory name for those belonging to the Ahmadi faith, declared non-Muslims by state in 1974),” he said.

But it’s not indifference to these rights issue alone that keeps journalists from reporting on them. Senior journalist and communication expert, Babar Ayaz, says it is also quite dangerous to write about “the victimisation of Ahmadis, Christians or Hindus”.

Nevertheless, he added: “Journalists have to write what is right. Threats and killings are hazards of this job living in an increasingly intolerant society.”

He remembered when he wrote a piece on the attack on the massacre of Ahmadis in Lahore [in May 2010], he received a couple “abusive phone calls”. He also received some angry messages on a chapter in his book titled: What’s Wrong With Pakistan? The book, which was published in August criticises Islamic laws in Pakistan.

“But we are small fry,” said Ayaz. “When Nawaz Sharif expressed condolence on the killings of ‘our Ahmadis bhais [brothers]’ some mullahs said that by calling them ‘bhai’ he had committed a sin. The extremists have no logic but they have muscle power,” he added.

According to Aamer Mahmood, who heads the press section of the Ahmadiyya Jammat, and is in regular touch with several journalists: “The fear among them is palpable. While many empathise with us for the way our rights are trampled, they say their hands are tied. Some are scared of the wrath of the extremists; others fear they will lose their jobs.”

“It is indeed becoming more dangerous to write on these issues, in any language,” agreed Kamila Hyat, a rights activist and former editor of English daily The News. “I believe that while sections of the English language press remain relatively liberal, more and more are succumbing to the bias and intolerance we see everywhere,” she pointed out.

“The manner in which the ‘agenda’ for news is set, notably by the electronic media, also shoves minority issues to the sidelines, and intolerant mindsets exist everywhere — even among the educated,” she said.

With seven journalists having lost their lives since January this year, according to the 2013 Impunity Index report by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CJP), just last year, Pakistan which was ranked tenth, has moved two spots up at eighth position for the worst place for the press. Further, it has been declared more dangerous than Russia, Brazil, Nigeria and India.

According to the CJP, 28 Pakistani journalists have been murdered since 1992 in connection with their work, 27 of whom were killed with impunity. The deaths of 24 additional killed during the same period cannot be confirmed as “targeted.”

“Doing journalism in Pakistan is not easy, which is ranked the third most dangerous country for reporting after Syria and Egypt,” observes Mazhar Abbas, former secretary general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, a formidable voice fighting for the rights of journalists. While journalists continue reporting despite threats particularly those working in the Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA), Balochistan and even in the southern port city of Karachi, Abbas said, reporters from the Punjab province seemed comparatively safer.

But not anymore, it seems.

Abbas said every threat should be taken seriously. “The letter to Tanveer could be an individual act or from a group. The government and administration need to probe this matter and find out about the person who sent this letter in the first place. Journalists reporting on sensitive issues should do so responsibly; their reports should be factually correct with minimum expression that can lead to stoking up controversy.”

This article was originally posted on 23 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

In May 2010, terrorists attacked two mosques belonging to the Ahmadi community. Ninety-four people were killed and more than 120 were injured. (Photo: Aown Ali / Demotix)

As the Muslim festival of Eid ul Adha drew to a close last week, it left a bad taste in the mouth of several Pakistanis when they heard that those belonging to the Ahmadi community were stopped from performing the ritual of animal sacrifice because they are “non-Muslims”.

According to a news report by Express Tribune, police raided a house of an Ahmadi man in Lahore, Punjab, and took him into custody. Police released him only after Ahmadi community elders intervened, giving written assurances that the man will not perform a sacrifice.

“We have slid towards the deep,” said rights activist and filmmaker Feryal Gauhar, quoting Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, blaming the government for not taking action.

“The spiral is rapidly spinning out of control. We are reduced to being passive bystanders to the tragedy that is being played out by forces of obscurantism,” she said.

“I think it’s deplorable and yet another instance of official persecution of the Ahmadis,” said Zohra Yusuf. But she said it was unclear under which law the police took action. “This indicates that intolerance has seeped into the police force, particularly in the Punjab,” she said.

The spokesperson of the Ahmadiyya Jammat in Pakistan, Saleemuddin (who uses his first name) said: “The police should not have given into the pressure of a few hardliners; this only strengthens them further.”

While only two cases surfaced this year, last year, too, a couple of cases were reported. Many fear if not nipped in the bud, this could set precedence for the coming years.

To Pakistani journalist and rights activist Beena Sarwar the episode is reminiscent of Nazi Germany and the persecution the Jews faced. “It goes against the basic tenets of humanity and justice, and the Islamic principle of ‘to you your faith and to me, mine’.”

“Pakistan must, for its own sake, take a firm stand against any such vigilantism and witch-hunting and intrusion into citizens’ personal lives and faith,” Sarwar said.

Every year, Muslims from all over the world gather in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and perform Haj, between the 8th to the 12th day of the Islamic month of Zil Haj. Among a series of rituals performed that date to the time of Prophet Abraham, is the sacrifice of animals — usually a goat or a sheep (although cows and camels are also slaughtered) and the meat is distributed among relatives and the less fortunate.

“Offering animal sacrifices, particularly on the blessed days of Eid-ul-Adha, is a quintessential Muslim practice that all Muslims deeply cherish. For police to strip Ahmadis of this precious right is a callous and cruel act,” responded Amjad Mahmood Khan, president, Ahmadiyya Muslim Lawyers Association, which is based in the United States, through an email exchange.

“Yes, it is a ritual performed by Muslims, and Ahamdis are not Muslims,” Qari Shabbir Ahmed Usmani, a cleric who lives in Chenab Nagar, Punjab, where 95 percent of its population belong to the Ahmadi faith.

While the Ahmadis, consider themselves Muslims, they believe that Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, a 19th century cleric, “was the messiah promised by God” which is unacceptable to all other Muslim sects.

In 1974, the state of Pakistan declared Ahmadis to be non-Muslims. According to Pakistan’s constitution, they cannot call themselves Muslims, are banned from referring to their places of worship as mosques and cannot sing hymns in praise of the Prophet Muhammad. There are between 2-5 million Ahamdis living in the country.

But Usman, who heads the International Kahtme Naboowat Momin, one of the several religious movements in Pakistan, that aims to protect the sanctity of Prophet Muhammad is not in favour of the banning Ahmadis from performing the sacrifice. “In Chenab Nagar, no Ahmadi was stopped carrying out the sacrifice,” he said.

This was confirmed by Aamer Mahmood, in charge of the press section of the Ahmadiyya Jammat, who lives in Chenab Nagar.

But strong armed tactics to scare the Ahmadis is not restricted to Punjab alone. In September, four Ahmadis were killed in Karachi for their faith, said Mahmood.

In addition, he said, over 60 Khatme-Naboowat Conferences were held on or around September 7 (the day Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims) across Pakistan. Mahmood said a hate campaign forms an integral part of the conferences. The followers are incited to kill Ahmadis as part of Muslim edict.

“Earlier a handful would be held, but this time there was a record number which shows state collusion in stoking anti-Ahmadi sentiment.” he said.

“They are lying,” said Usmani. “We are against every form of violence; they are badmouthing Islam. In fact, had that been the case, do you think there would have been a single Ahmadi still alive in Pakistan?” he said during a phone interview.

“I have before me scores of published press statements and edicts by various Khatme Naboowat leaders from various Urdu newspapers to kill us or openly threatening us to leave Pakistan,” Mahmood countered.

He said he has pamphlets listing the names and addresses of Ahmadi families alongside messages inciting murder.

According to Khan: “The extreme views of a certain militant segment of Pakistan have permeated state institutions and law enforcement. Until and unless the state of Pakistan recognizes that it is only Allah’s place to judge whether someone is a true and righteous Muslim, it will continue down a perilous path towards lawlessness and injustice.”

Gauhar said sadly: “Mohammad Ali Jinnah [the country’s founder] would not own this Pakistan.”

Meanwhile, in the United States, a Congressional-appointed bipartisan federal body yesterday urged President Obama to raise concerns about the “dire religious freedom situation” in Pakistan during their meeting.

“Given that President Obama and Sharif reportedly will be discussing how best to counter violent extremism, we urge the US to incorporate concern about freedom of religion into these conversations,” said Robert George, Chairman of the US Commission of International Religious Freedom.

“To successfully counter violent extremism, Pakistan must have a holistic approach that ensures that perpetrators of violence are jailed, and addresses laws that foster vigilante violence, such as the blasphemy law and anti-Ahmadi laws.

“For the sake of his country, the Prime Minister should be pressed to take concrete action,” George said.

Based on findings of United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), Pakistan represents one of the worst situations in the world for religious freedom, he noted.

“The violence extremists perpetuate threatens all Pakistanis, including Shias, Christians, Ahmadis, and Hindus, as well as those members of the Sunni majority who dare to challenge extremists,” he said.

This article was originally posted on 22 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org