21 Aug 2020 | News, Opinion

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114590″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]August is meant to be a quiet month for news. But this month has been anything but quiet.

Every day the world has been exposed to a new and sustained attack on our basic human rights. In every corner of the world, our collective rights to free expression and our freedom of association seem to be under siege. And for too many, the most basic of our human rights – our right to life, to live in peace – is, too often, not considered a right at all by those who will use any tool at their disposal to retain their power and the status quo.

It seems that at any given time, there is always at least one government, one repressive regime or a non-state actor using their power to remove the rights of citizens.

The results are heart-breaking to watch and devastating for the families that are torn apart and left scared and isolated.

This week alone, we have seen images of a teenager from Sudan who drowned as he tried to get to the UK to plead asylum – a 16-year-old who was fleeing war and a military regime.

In Russia, the leader of the opposition, Alexei Navalny, is in a coma after reportedly being poisoned as he travelled back to Moscow. His wife is being refused access to his hospital bed.

The first-hand account from a Uighur teacher who had been exposed to the Xinjiang concentration camps was published this week. It is a harrowing personal testimony of a genocide.

In Hong Kong, the impact of the national security law continues to be felt far and wide with arrests and intimidation now being deployed to silence dissenters. And its reach is now being felt outside of China. On university campuses around the world, professors and academics are starting to consider the impact their teaching will have on Chinese students. Knowledge has become a vulnerability for too many Chinese students as they return to Hong Kong. Seats of academic enlightenment and learning are having to change what they teach and how they teach it in order to protect their students – this is not acceptable.

And of course, we have followed in horror what is happening in Belarus, on European soil, as Lukashenko refuses to leave office and hold free and fair elections. Journalists arrested, protestors tortured and artists and musicians sacked for standing up to the regime.

These are the stories which have held the news cycle and grabbed our attention. However, for each example I cite there are a further dozen cases of tyranny that need to be exposed and challenged, in every corner of the earth. And yet, woven through each of these affronts to our basic rights is a single thread of brave men and women who refuse to be silenced. A cadre of freedom fighters determined to protect their rights and ours. They do not know each other and they likely never will meet but they are fighting the same fight. They are holding back the tide of tyranny and they are risking everything to do so.

The question for all of us is what can we do to help? How can we support people on the other side of the world as they stand up to tyrants? How can we make sure they know that we stand with them?

At Index, it is our role but also our responsibility to stand with them. To tell their stories, to publish their work, to make sure that the world knows what is happening to them. But to do that we need your help. We need your support, emotional and of course financial. Behind each of these headlines is a person, a family, a life. Their lives are as valuable as ours but their journeys are at the moment just too hard. To support them we need your help – please donate to Index, just a five pounds a month will enable us to tell someone else’s story.[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=”Donate to Index” color=”danger” size=”lg” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fregular-donation-form%2F%3Famt%3D%25C2%25A35|||”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”13527″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Jul 2020 | Index Shots, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpbIyNZ7WKI”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to watch” category_id=”41199″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

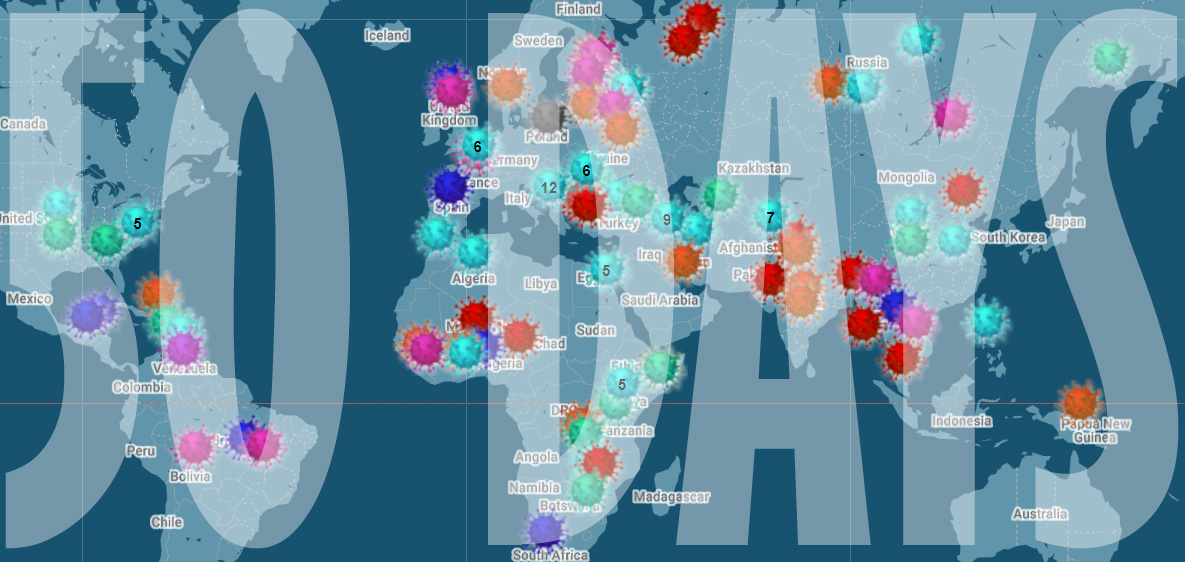

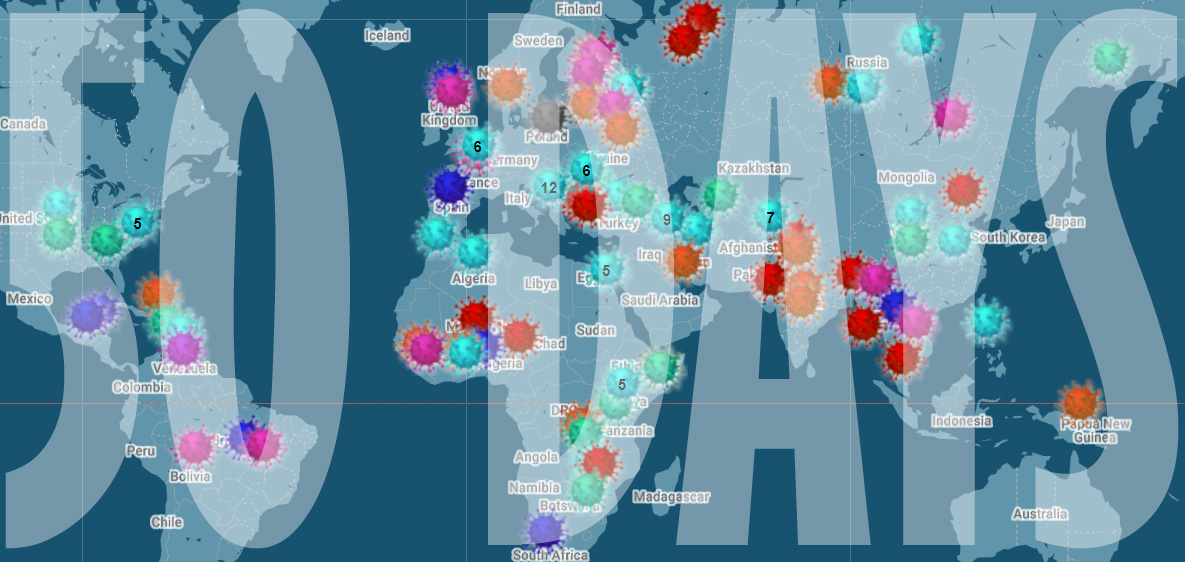

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Apr 2020 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

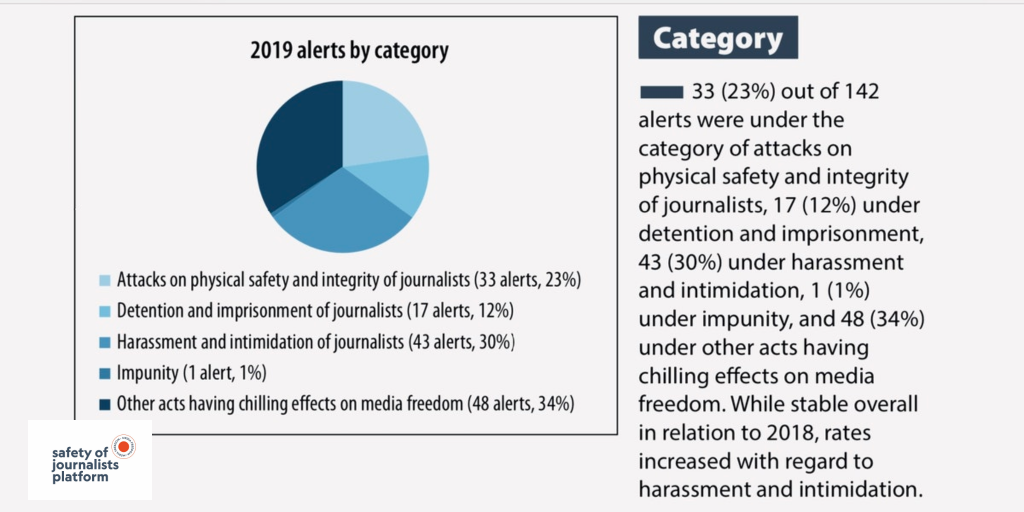

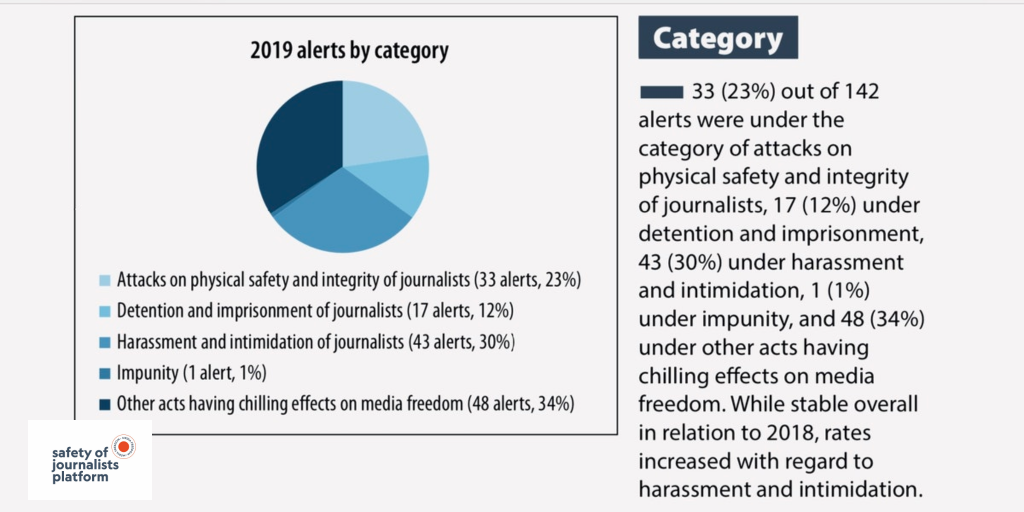

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]