31 Jul 2019 | Czech Republic, Germany, Journalism Toolbox Russian, South Africa, Yemen

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Пятеро молодых журналистов пишут с разных уголков мира – Йемена, Южной Африки, Германии, Индии и Чешской Республики – об обеспокоенности по поводу их профессии, а также о надеждах, которые они возлагают на неë

Выше: Молодая журналистка докладывает из Оттавы, Канада”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Из Йемена

«Мы не можем противостоять пропаганде с помощью цензуры»

Йеменское правительство не должно оценивать объективность репортажей, но всë же есть надежда на бóльшую свободу, – говорит Ахлам Мохсен

В ϶том году Йемен опять оказался почти в конце списка, оценивающего свободу прессы, заняв в рейтинге 167 место среди 180 стран, согласно Индекса свободы прессы. Журнализм в Йемене преисполнен противоречий. Прямой цензуры в условиях коалиционного правительства, возможно, стало меньше, но активизировались нападения на журналистов и критиков.

Я приехал в Йемен – страну, где я родился, но которою едва знаю – из США вскоре после того, как президент Йемена Али Абдалла Салех ушел в отставку в начале 2012 года. Я занимаю активную гражданскую позицию и поэтому был поражен, что в Штатах мы не можем добиться прав на территорию парка, а в Йемене им удалось свергнуть правительство.

Йемен – единственная арабская страна, кроме Иордании, которая приняла закон о свободе информации

После Арабской весны в 2011 году йеменские журналисты стали свидетелями ряда побед, таких как принятие закона о свободе информации, который обнадёжил на бóльшую прозрачность в деятельности правительственных учреждений. Йемен – единственная арабская страна, кроме Иордании, которая приняла этот закон. Однако, как засвидетельствовал непродолжительный расцвет свободы прессы, последовавший за объединением в 1990 году, победы не всегда оказываются незыблемыми и прогресс не всегда последовательный.

Уже четыре месяца газета «Йемен Таймз» («The Yemen Times»), где я работаю, пытается получить доступ к правительственным нефтяным контрактам с зарубежными и транснациональными корпорациями. Мы могли бы попробовать найти слитые документы, но нам важно получить их прямо от правительства, чтобы знать все условия и чтобы будущие решения были полностью прозрачными.

С возрастанием количества газет, радиостанций и телевизионных каналов, которые сотрудничают и финансируются разными политическими партиями и влиятельными частными лицами, появляется реальная обеспокоенность, что эти медиа-организации используются для распространения пропаганды. Телевизионный канал «Йемен Тудей» (Yemen Today) был закрыт правительством в июне по обвинению в подстрекательстве против нынешнего правительства во время топливного кризиса в стране.

Странно, что много критиков правительственной цензуры молчали в это время и не осудили этот шаг, скорее всего потому, что станция принадлежала бывшему диктатору Салеху. А этот шаг очень угрожающий. Разрешая правительству быть судьей того, что объективно и что не объективно в репортажах, мы передаем им власть, которая должна быть только в руках общественности. Мы не можем противостоять пропаганде с помощью цензуры. Правительству нужно не только прекратить цензуру, а и привлекать к ответственности тех, кто преследует журналистов и оказывает давление на них, чтобы последние не вынуждены были прибегать к самоцензуре – а это, несомненно, намного более серьезная проблема в стране, нежели прямая цензура.

Быть женщиной-журналистом в Йемене также сопряжено с определенными проблемами. Я видел молодых женщин, который спешили на место бомбардировки или место преступления, чтобы первыми осветить события. Часто, хотя они и пребывали первыми, солдаты окружали их и заботились об их безопасности. А мужчины-журналисты, их коллеги, пробегали мимо них к месту происшествия. Эта глубоко укоренившаяся проблема тесно связана с будущим женщин в более широком смысле. Но есть много обнадëживающих вещей в Йемене. К примеру, страна близится к 30-ти процентной квоте представленности женщин в правительстве, и женщины продолжают утверждать своë право голоса в общественной сфере.

Ничто нельзя считать до конца определëнным в Йемене. Возможны разные сценарии развития страны: от успешного перехода к демократии и до гражданской войны. Несмотря на все проблемы и риски освещения событий в Йемене, я оптимистичен касательно будущего журналистики здесь. Закон о свободе информации – радикальный закон, и, если его будут соблюдать, это даст нам право знать практически всë о том, чем занимается наше правительство. Если мы сможем сделать этот закон значимым, пользуясь им, а не просто имея его на бумаге, то у нас, журналистов, и общественности неплохие перспективы.

Ахлам Мохсен

Ахлам Мохсен, 26 лет, йеменский и американский писатель, заместитель главного редактора «Йемен Таймз», проживающий в Сане

Из Германии

«Журнализм ещë никогда не был таким захватывающим»

Катарина Фрик прошла семь стажировок в Германии, чтобы начать свою карьеру, и все же оптимистично настроена относительно новых проектов финансирования средств массовой информации

В Германии, как и во многих других местах по всему миру, редакции закрываются, рекламный рынок приходит в упадок, а газетная индустрия сократила свой оборот почти на четверть за последнее десятилетие. Почему я всë-таки хочу стать журналистом? Потому что он ещë никогда не был таким захватывающим.

Я из семьи журналистов. Мои мама и папа работали в сфере журналистики и коммуникаций почти всю жизнь. Многое изменилось с тех времëн, когда они начинали работать в редакции местной ежедневной газеты 30 лет назад, и они согласны, что конкуренция сейчас более жесткая. Мою маму сразу взяли на еë первую работу, без какого-либо предыдущего опыта. Сегодня об этом не может быть и речи. Я прошла семь стажировок во время учëбы – некоторые с небольшой заработной платой, некоторые совсем без неë.

Половину этих стажировок и своих работ я получила благодаря своим контактам и связям, половину – без них. Хорошие контакты играют более важную роль, чем прежде, и это то, что я ненавижу в этой сфере. Я всегда хотела достичь всего сама, но я пришла к выводу, что так не получается. По крайней мере, не в том случае, когда ты хочешь попасть в большую медийную компанию с определенными традициями.

Потому я всë более и более склоняюсь к новым и свежим подходам к средствам массовой информации, где идеи и креативность ценятся больше, чем знакомство с кем-то, как, к примеру, в журналистских стартапах. В условиях финансового кризиса люди с креативными идеями и предпринимательскими навыками играют более важную роль, чем прежде. Я убеждена, что не существует однозначного решения проблемы сохранения будущего журнализма; я думаю, их много. Сейчас самое время поэкспериментировать и испытать бизнес-модели с разными финансовыми схемами и разным идейным содержанием.

В Германии немногие читатели готовы платить за онлайн статьи, и только некоторые издательства проявили смелость поэкспериментировать с моделями осуществления платежей или платными стенами. Ежедневная газета «Ди Вельт» (Die Welt), к примеру, использует «протекающую платную стену», похожую на те, которые используются «Нью-Йорк Таймз» (The New York Times) и «Дейли Телеграф» (The Daily Telegraph) в Великобритании, разрешая пользователям читать 20 статей бесплатно каждый месяц на одном браузере. «Сюддойче Цайтунг» (Süddeutsche Zeitung), одна из наиболее крупных ежедневных газет в Германии, недавно объявила, что они тоже введут модель подобного рода к концу года.

Один инновационный проект, который недавно преуспел в Германии – это Краутрепортëр (Krautreporter) (название построено на основе аналогии с английским словом «crowd» – толпа). Это интернет-издание было учреждено 28-ма относительно известными внештатными журналистами, которые хотели создать онлайн публикации с подробными докладами. Их не интересовало количество просмотров издания, и они хотели исключить рекламу. Поэтому они попросили денег в общественности. Их целью было собрать 900,000 евро с 15,000 доноров за 30 дней. За последние несколько часов до истечения срока сбора денег нужное количество людей пожертвовали по 60 евро каждый. В конце концов было собрано более одного миллиона евро – предположительно рекордная сумма, когда-либо собранная с общественности на журналистский проект в Германии. Журналисты будут зарабатывать от 2 до 2,5 тысяч евро в месяц, и это позволит им всецело заняться их исследованиями и не думать постоянно про следующие задания.

Краутрепортëр не собирается прятать каждую статью за платной стеной, а будет доступным для всех; но плата в размере 5 евро в месяц предоставит пользователям привилегии, такие как возможность комментировать статьи, участвовать в мероприятиях и контактировать с журналистами. Взаимодействие и интеракция с читателями и пользователями на таком уровне – это всë ещë новшество для большинства традиционных средств массовой информации, и многие издатели пристально наблюдают за этой концепцией членства читателей.

Конечно, новые проекты почти никогда не обходятся без осуждения. На заре деятельности Краутрепортëр критиковали за отсутствие чëтких подробных изложений и запланированного содержания, а также за их подбор журналистов (в основном все были мужчинами и при этом выходцами из похожей среды). Вся германская индустрия средств массовой информации будет пристально следить за сайтом, когда он выйдет в прямой эфир в октябре. Надежды большие. Однако, я думаю, что самое главное – это их стремление инициировать что-то новое и свежее.

Несмотря на экономические условия, я отказываюсь верить в то, что журнализм умирает, или что я не найду работу. Всë в наших руках – в руках молодых журналистов, и только мы можем изменить ситуацию и поэкспериментировать. Я знаю из тех проектов, в которых я была задействована во время учëбы, что существует некая атмосфера, когда работаешь в стартапе, что-то вроде групповой динамики, когда все тянуться в одном направлении. Я твëрдо убеждена, что я буду работать журналистом в ближайшие годы. Никто не знает, какой именно будет эта работа журналиста, но я уверенна, она будет интересной.

Катарина Фрик

Катарина Фрик, 27 лет, в данный момент готовит магистерскую работу по специальности «Журналистика, средства массовой информации и глобализация», а также работает внештатным репортёром в немецком информационном агентстве Дойче Прессе-Агентур (ДПА). Она также возглавляет свой собственный журналистский проект, который занимается вопросами устойчивого развития (www.sustainyourfuture.com)

Из Чешской Республики

«Я предвижу непростое будущее – для журналистов и для читателей»

Столкнувшись с высоким уровнем безработицы у себя на родине, итальянский журналист Лука Ровинальти переехал в Прагу, но светская хроника приехала с ним

Когда новости о десятиборце Романе Себрле и модели Габриэле Краточвиловой в последнее время стали ведущими на каналах одной из главных частных телевизионных компаний в Чешской Республике, меня это не удивило. Я начал свою карьеру в Италии и поэтому привык к такому подходу в журналистике, где используется стиль жëлтой прессы и в центре внимания находятся знаменитости. Похоже, что этот подход приобретает в Европе все большие и большие масштабы.

Когда я работал на ведущие частные телеканалы в Италии в 2000-х годах, журнализм в то время превращался в территорию сплетен, и материалы оформлялись так, чтобы спровоцировать эмоции у публики. Я помню, как целыми днями сидел на пляже в Римини, интересуясь у людей, как усовершенствовать технику загара, и спрашивая у девушек об их подготовке к пляжному сезону.

В 2010 году я приехал в Чехию на год, чтобы поработать над правовой программой в Карловом университете и решил остаться здесь, поскольку на родине значительно сокращались рабочие места. У меня польские корни, так что я чувствую себя довольно комфортно в восточной Европе. Понемножку учусь говорить. Я всë ещë внештатно работаю на компании в Италии, но меня интересует сотрудничество с англоязычными изданиями здесь и за рубежом.

У меня достаточно многообразный карьерный опыт: переезд из Эмилии-Романьи в северо-центральной части Италии в Милан, а потом в начале 2010 года в Чешскую Республику, где я сейчас руковожу Пражским международным пресс-клубом (International Press Club of Prague). Этот опыт помог мне выстроить идею поликультурного журнализма, без национальных барьеров и с уважением к национальным различиям. Я очень надеюсь, что эта концепция будет развиваться, так как мир становиться все более и более глобальным и всë больше и больше местных изданий публикуются на нескольких языках, а коллеги с разных стран работают вместе.

В 2013 году я выступил соучредителем Пражского пресс-клуба. Я понял, что здесь можно улучшить возможности взаимодействия, а существующие организации не были достаточно активными. Но, как я осознал ещë в Италии, чтобы стать журналистом, тебе не просто нужен кусок бумаги или журналистское удостоверение. Мне пришлось работать два года, прежде чем я смог получить членство в Ассоциации итальянских журналистов.

Сегодняшний уровень безработицы в Италии – составляющий 13% в целом и 43% для людей моложе 25 лет – значительно влияет на журнализм. Это также означает, что многие люди ищут работу за рубежом. Марио Джордано, главный редактор TG4, одной из ведущих новостных программ в сети «Медиасет» (Mediaset) в Италии, дал мне такой совет: «В журналистике нужно поменять образ мышления, а не просто методы. Те, кто знают, как это сделать, выживут. Запомни: базовые принципы журнализма остаются теми же: и в ситуации, когда ты пользуешься почтовым голубем, и тогда, когда используешь твит».

Я полностью с этим согласен. Журналистика в Италии превратилась в настоящую полосу препятствий, которая требует от репортëров всегда быть в курсе новых технологий и адаптироваться к ним. Таковы условия рынка, где почти нет места для молодых талантов. Многие функции теперь перекладываются на плечи внештатных работников, которые получают за это совсем маленький гонорар.

На моëм первом месте работы в телевизионной редакции я очень неохотно переходил от «чисто» журналистской работы до изучения методики киносъемок, технического оборудования, видеомонтажных работ и трансляции. Но сейчас я понимаю, что человек-оркестр имеет крайне важное значение на сегодняшнем рынке.

В обществе, где блогеры и гражданские журналисты изо дня в день стают все более важными, игнорировать инновации – бессмысленно. Принципиально важное значение имеет понимание новых технологий и использование их надлежащим способом с надеждой, что читатели смогут отличить фактическое от приукрашенного и надëжное от недостоверного.

С каждым днëм всë больше и больше источников засыпают нас информацией такого рода, где реальные новости перемешаны с обманом, а реклама замаскирована под информацию. Философия «заплати за каждый клик» сводит всю важность статьи к первым трëм словам. Я предвижу непростое будущее: и для читателей, которым нужно будет отличать новости от не-новостей, и для журналистов, которым нужно будет научиться выживать в условиях всевозрастающей конкуренции, предоставляемой не только их собратьями по перу, а также людьми совершенно других профессий, включая моделей и спортсменов.

Сейчас я понимаю, что человек-оркестр имеет крайне важное значение на сегодняшнем рынке

Лука Ровинальти

Лука Ровинальти, 27 лет, итальянский внештатный журналист, проживающий в Праге, Чешская Республика

Выше: Журналисты работают на своих ноутбуках во время пресс-конференции для Инстаграма в Нью-Йорке

Из Южной Африки

«Журналистика данных – новый рубеж»

Атандиве Саба уверенна, что для журналистских расследований существует перспективное будущее – если только ей удастся вырвать общественную информацию из рук правительственных чиновников

Моë пристрастие к журнализму основывается на праве каждого человека иметь доступ к информации. Это право зиждиться на 36 статье конституции Южной Африки: «Каждый имеет право доступа к любой информации, находящейся в распоряжении государства; и к любой информации, находящейся в распоряжении другого человека, необходимой для осуществления или защиты каких-либо прав».

Закон о свободе информации был внесëн в конституцию в ответ на цензуру апартеида, но он постоянно пребывает под угрозой

Сегодня в нашем молодом демократическом государстве к этому праву относятся снисходительно, или же оно просто игнорируется, недооценивается, принимается как данность и правительственными чиновниками, и обществом в целом. Как у журналиста воскресной газеты «Сити Пресс» (The City Press) у меня часто возникают проблемы, когда я запрашиваю информацию или прошу правительственные агентства что-то прокомментировать. Совсем недавно моë заурядное требование предоставить школьную документацию всех образовательных заведений в стране, касающуюся планирования питания, повлекло за собой настоящую борьбу. Мне часто приходилось цитировать свои законные права и напоминать чиновникам, что информация принадлежит людям. Прошло много месяцев, а я всë ещë жду.

Наше демократическое правительство внесло закон о свободе информации в конституцию в ответ на цензуру апартеида, но он постоянно пребывает под угрозой. Законопроект о защите государственной информации, также известный как «засекреченный законопроект», тоже является предметом разногласий с 2010 года. Цель законопроекта – регламентировать государственную информацию, сопоставляя государственные интересы с гласностью и свободой выражения мнений. Такая регламентация определенно ограничила бы журналистов, и многие репортëры и осведомители оказались бы в тюремных камерах за разглашение секретной информации. Законопроект был утверждëн в парламенте в 2013 году, но закон так и не был принят.

Касательно будущего больше всего мене волнует следующее: если журналисты прилагают такие усилия, чтобы добыть информацию, то что это значит для остальных граждан в этой стране? Если ведомства отказывают в доступе к школьной документации, как родитель может получить такую информацию, чтобы защитить соблюдения прав своего ребенка?

Также вызывают серьезное беспокойство противоречивые заявления политиков и руководства, как например, призыв к общественности бойкотировать издания. В последние два года правящая партия Африканский национальный конгресс (АНК) и еë Юношеская лига пытались подвергнуть цензуре газеты «Сити Пресс» и «Мейл енд Гардиен» («Mail & Guardian») за опубликованные материалы, которые, как они полагали, оскорбили председателя партии. Также руководством нашей государственной вещательной компании ведутся переговоры о лицензировании и контроле журналистов.

Моë пристрастие к журналистике данных – или компьютеризованной журналистике – стало ещë более яростным после посещения конференции на эту тему в Балтиморе, США. Участие в конференции дало мне возможность рассуждать более критично о цифрах, которыми нас засыпают правительственные и неправительственные ведомства. Эта концепция ещë серьезно не разрабатывается газетами в Южной Африке, поскольку она требует слишком много времени, а рабочие места значительно сокращаются в этой сфере. Но всë же есть проблеск надежды. Один из моих редакторов как-то сказал, что это наш «новый рубеж», и в последние несколько месяцев я почувствовала, что репортажи на основе фактических данных получают больше поддержки в моей редакции.

Я помню, как один из координаторов в США сказал, что мне очень повезло приехать на конференцию из страны, где репортажи с использованием компьютерных технологий ещë на самом деле не стартовали. Я была озадачена. Потом я поняла, что он имел в виду массу неиспользованной информации в нашей стране, кладезь материалов, которые ждут, чтобы я применила к ним свои усвоенные навыки.

Атандиве Саба

Атандиве Саба, 26 лет, журналист-исследователь в «Сити Пресс», южноафриканской воскресной газете

Слева: Протестующие участвуют в демонстрации против законопроекта о защите информации в Кейптауне 17 сентября 2011 года

Из Индии

«Как выжить нравственному молодому журналисту?»

Бханудж Каппал расстроен, что редакторская беспристрастность в Индии подрывается владельцами средств массовой информации и предъявляемыми к журналистам требованиями придерживаться правил

Все более и более журналисты в Индии чувствуют себя изолированными и все больше подвергаются нападениям – и со стороны политических лидеров и правительства, и со стороны предвзятых интернет-троллей в лентах комментариев и социальных сетях, и даже со стороны собственных работодателей.

Заместитель редактора CNN-IBN Сагарика Гуз, как утверждает новостной сайт Scroll.in, получила указания от руководителей компании-учредителя Network 18 не размещать оскорбительные твиты о нынешнем премьер-министре Индии Нарендре Моди. Гуз отказалась подтвердить или опровергнуть это, но она сказала, что видит тревожную новую тенденцию, где предвзятость почитается, а «журналисты, которые убеждены, что политик – их закономерный противник, и поэтому они систематически допрашивают всех политиков, считаются предвзятыми». Позже она уволилась.

Это довольно тревожная картинка для молодых журналистов, таких как я. Мы видим, как быстро разрушается понятие редакционной независимости и беспристрастности под давлением владельцев средств массовой информации и руководства. И это не считая тех неопубликованных репортажей о безнравственной деятельности и компроматов, собранных редакцией. Эта тема всегда обсуждается молодыми журналистами, когда они собираются выпить.

Один из моих бывших однокурсников из школы журналистики настолько разочаровался своим опытом на популярном англоязычном новостном канале в Индии, что он решил бросить вещательную журналистику и работать в печатных средствах массовой информации.

«Они предпочитают транслировать репортажи визуального характера, а не те, которые отображают общественные интересы», – рассказал он мне. Ещë один мой однокурсник, который работал в ведущем печатном журнале, решил бросить журналистику вообще и вернутся в научные круги. Как подчеркнул в своей передовой статье недавно уволенный политический редактор «Оупен Мегезин» («Open Magazine») Хартош Сайн Бал: «Сегодня начинающие журналисты должны идти на компромисс с владельцами и руководством намного раньше в своей карьере, потому что они практически лишены защиты хорошего редактора».

Все это позиционирует перед молодыми журналистами дилемму. Оставаться ли в организации, где редакторская независимость подрывается? В ситуации сокращения рабочих мест и недостатка, заслуживающих доверия медийных организаций как выжить молодому журналисту и остаться преданным независимому нравственному журнализму? Более того, что же станет с идеалом свободного и критичного журнализма, если молодые репортёры видят массу общественных примеров, как страстный бескомпромиссный журналист очень быстро стает безработным?

Это крайне важные вопросы касательно будущего журнализма в стране, где средства массовой информации становятся одним из наибольших страшилищ в общественной дискуссии. Молодым журналистам ничего не остается, кроме как наблюдать беспомощно, как их профессия, их будущее втягивается в грязь поколением, которое уже сделало себе имя и заработало себе на пенсию. Присовокупите к этому технологические и экономические трудности, с которыми журналистика сталкивается уже в мировом масштабе – «стримификейшн», «чэнелизм», превращение культурного журнализма в «содержательный» и сведения его к «статейкам» – и внезапно мне трудно осуждать моего друга за его выбор относительной безопасности научной карьеры. Будущее выглядит безрадостно.

Но молодые журналисты всë же не совершенно беспомощны. Многие из нас реагируют на ситуацию таким образом: занимаются нештатной работой, отказываясь от экономической обеспеченности в пользу свободы выбора материала и верности нравственности. Мы создаем неофициальные сети с целью поддержки и обмена информацией и в режиме онлайн, и в реальной жизни. Идея состоит в том, что донести репортаж до общественности намного важнее, чем признание чьего-либо авторства и заслуг.

И для каждого Баззфид клона интернет предоставляет место, где проблемы проигнорированные ведущими средствами массовой информации, получают должное внимание и анализ. Вебсайты, как, к примеру Scroll.in и Yahoo! Originals, дают молодым внештатным журналистам возможность заниматься подлинным, независимым репортëрством, до которого традиционным средствам массовой информации больше не дела. Он только формируется и далек от совершенства, но это единственная надежда для журналистики в Индии – только так ты можешь быть независим от корпоративных и политических интересов.

Бханудж Каппал

Бханудж Каппал, 26 лет, внештатный журналист, проживающий в Мумбаи. Он готовит репортажи для ряда изданий, включая «Санди Гардиен» («Sunday Guardian»), Yahoo! India и GQ India. Он получил степень магистра в школе журналистики, медиа и культуры Кардиффского университета

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jul 2018 | News, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

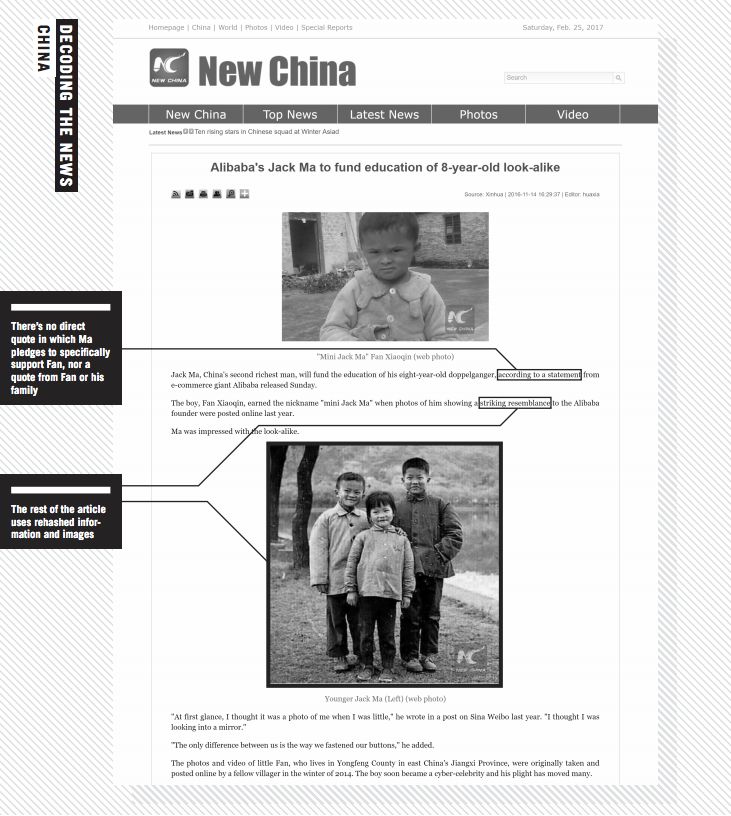

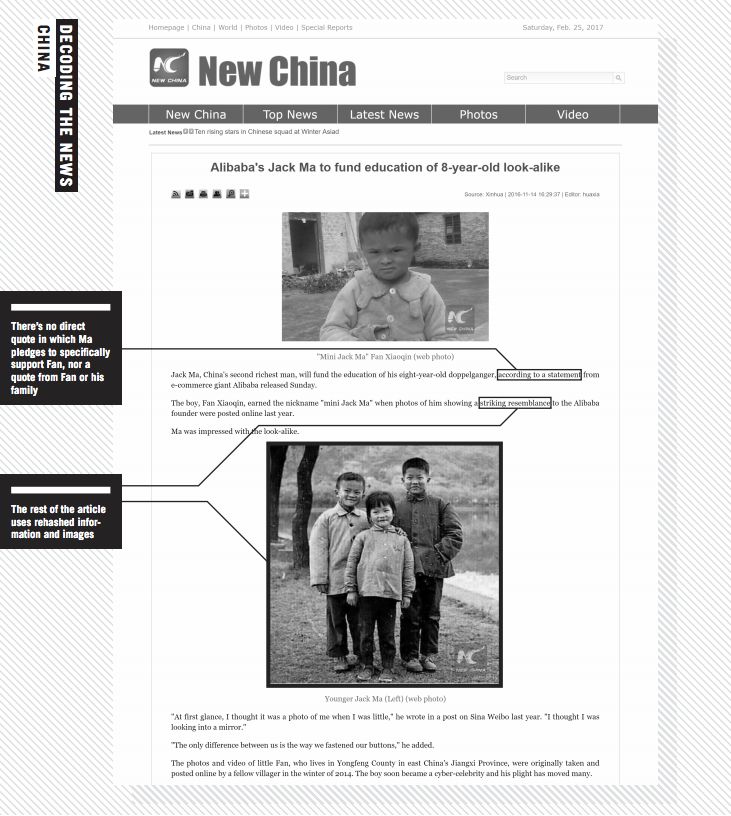

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

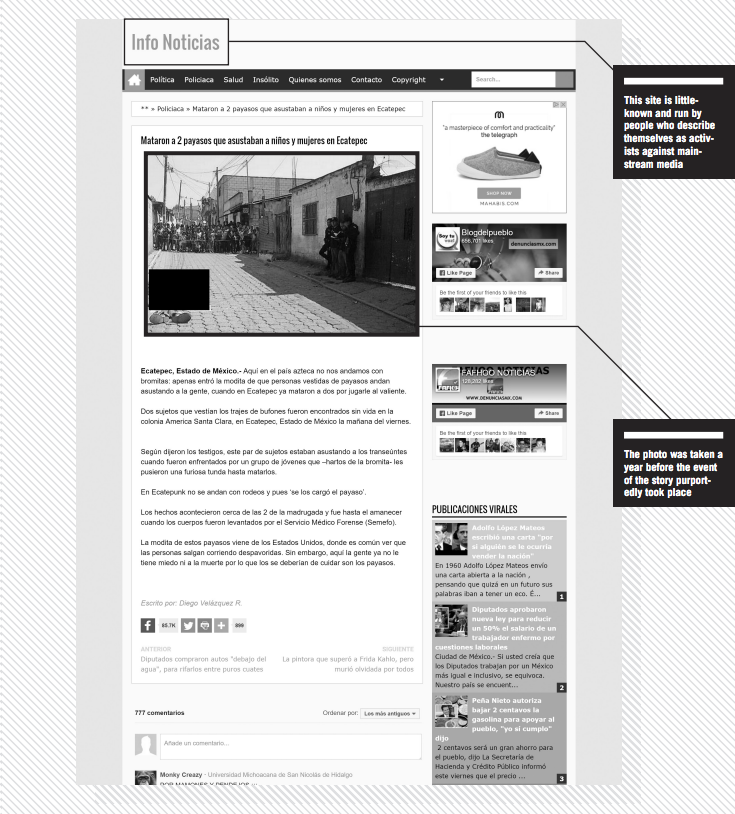

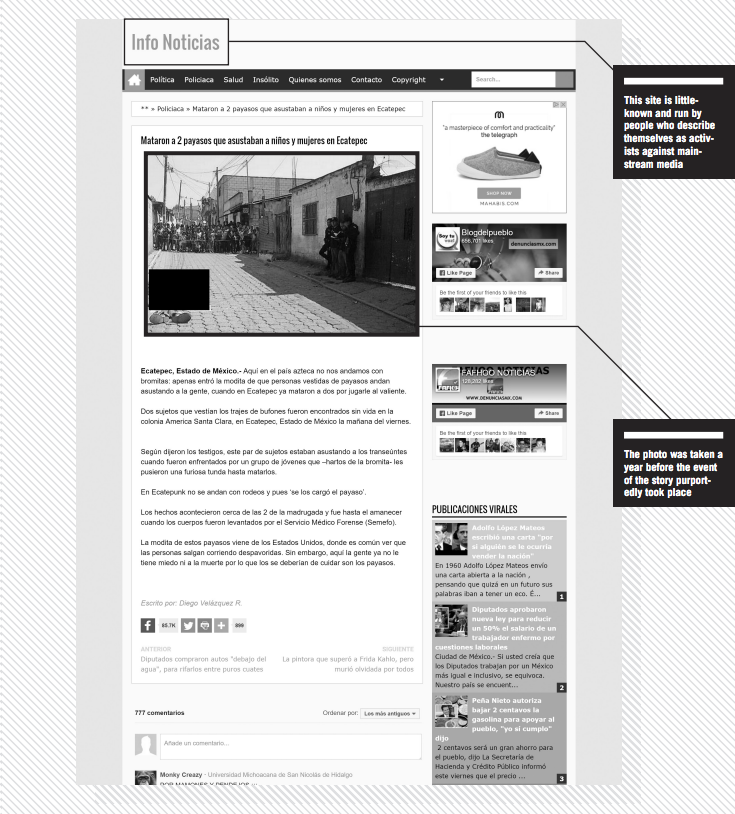

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

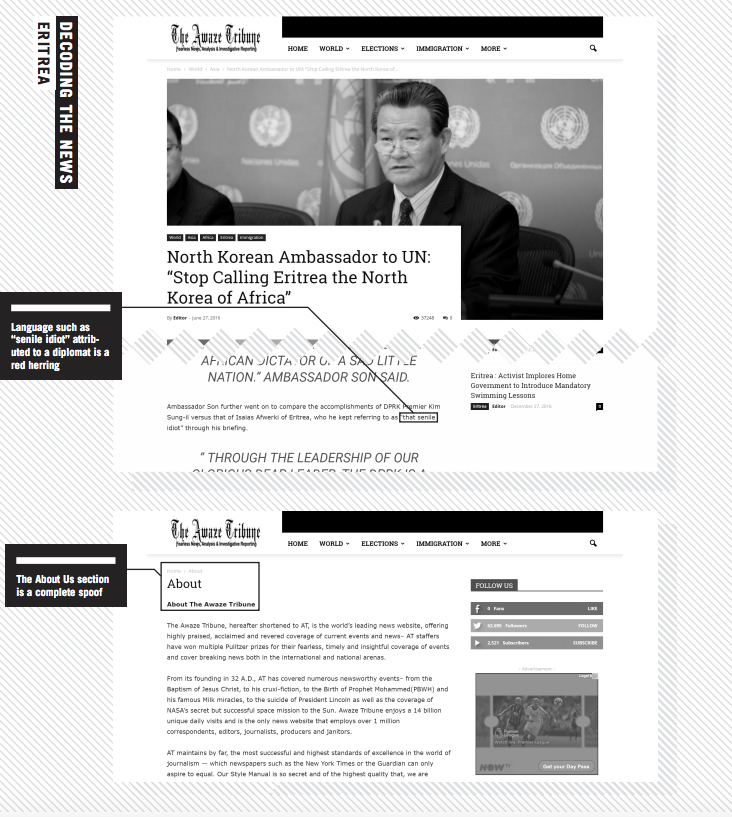

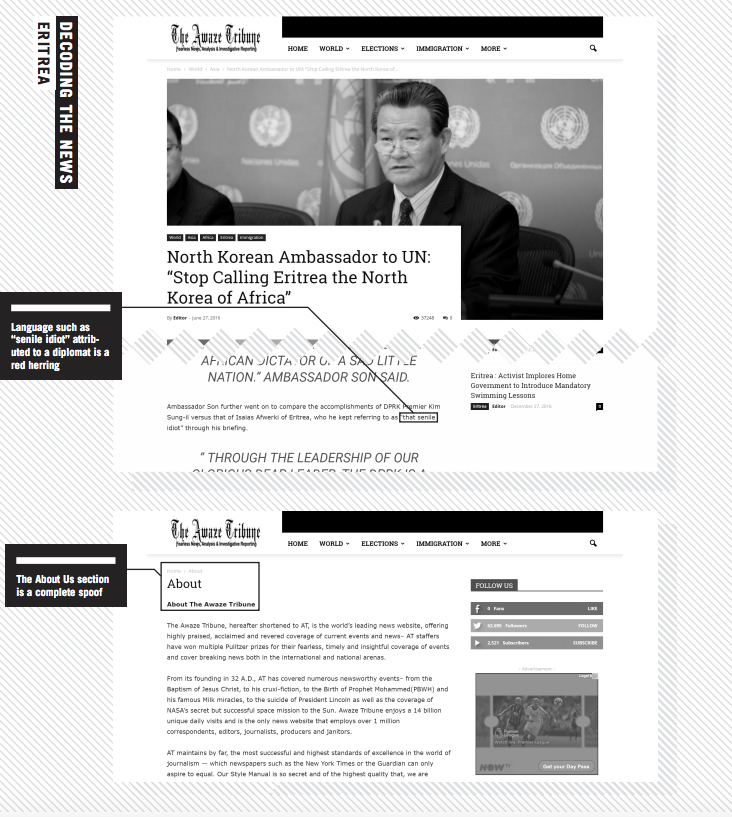

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

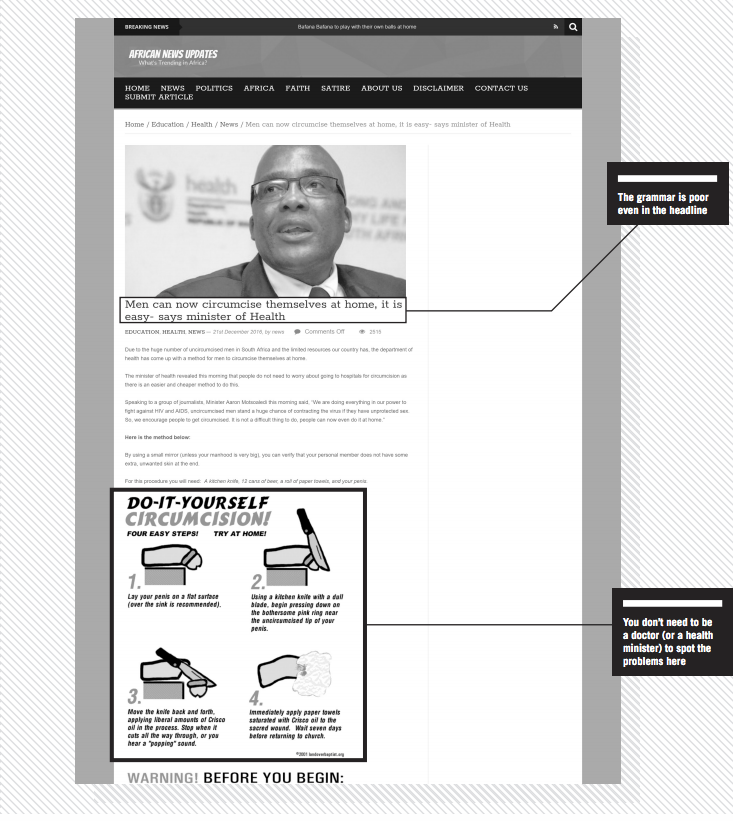

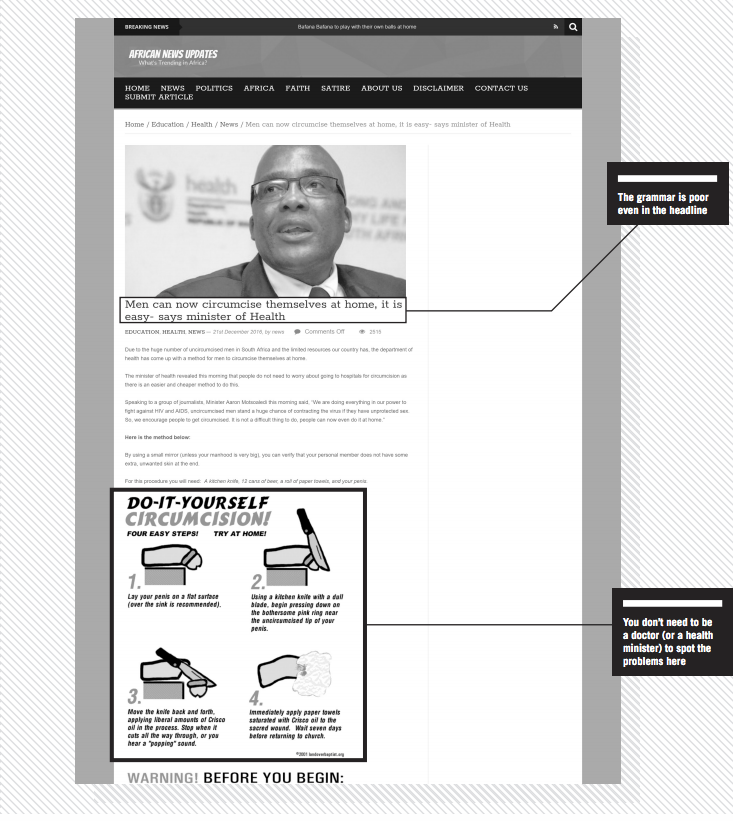

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Apr 2018 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Omar Mohammed, Mahvash Sabet, Simon Callow and Lucy Worsley, as well as interviews with Neil Oliver, Barry Humphries and Abbad Yahya”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends.

In this issue, we examine the various ways and areas where historical narratives are being changed, including a Q&A with Chinese and Japanese people on what they were taught about the Nanjing massacre at school; the historian known as Mosul Eye gives a special insight into his struggle documenting what Isis were trying to destroy; and Raymond Joseph takes a look at how South Africa’s government is erasing those who fought against apartheid.

The issue features interviews with historians Margaret MacMillan and Neil Oliver, and a piece addressing who really had free speech in the Tudor Court from Lucy Worsley.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”99222″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

We also take a look at how victims of the Franco regime in Spain may finally be put to rest in Silvia Nortes’ article; Irene Caselli explores how a new law in Colombia making history compulsory in school will be implemented after decades of conflict; and Andrei Aliaksandrau explains how Ukraine and Belarus approach their Soviet past.

The special report includes articles discussing how Turkey is discussing – or not – the Armenian genocide, while Poland passes a law to make talking about the Holocaust in certain ways illegal.

Outside the special report, Barry Humphries aka Dame Edna talks about his new show featuring banned music from the Weimar Republic and comedian Mark Thomas discusses breaking taboos with theatre in a Palestinian refugee camp.

Finally, we have an exclusive short story by author Christie Watson; an extract from Palestinian author Abbad Yahya’s latest book; and a poem from award-winning poet Mahvash Sabet.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special report: The abuse of history “][vc_column_text]

A date (not) to forget, by Louisa Lim: The author on why her book about Tiananmen would be well-nigh impossible to research today

Who controls the past controls the future…, by Sally Gimson: Fall in line or be in the firing line is the message historian are receiving from governments around the world

Another country, by Luka Ostojić: One hundred years after the creation of Yugoslavia, there are few signs it ever existed in Croatia. Why?

No comfort in the truth, by Annemarie Luck: It’s the episode of history Japan would rather forget. Instead comfort women are back in the news

Unleashing the past, by Kaya Genç: Freedom to publish on the World War I massacre of Turkish Armenians is fragile and threatened

Stripsearch, by Martin Rowson: Mister History is here to teach you what really happened

Tracing a not too dissident past, by Irene Caselli: As Cubans prepare for a post-Castro era, a digital museum explores the nation’s rebellious history

Lessons in bias, by Margaret MacMillan, Neil Oliver, Lucy Worsley, Charles van Onselen, Ed Keazor: Leading historians and presenters discuss the black holes of the historical universe

Projecting Poland and its past, by Konstanty Gebert: Poland wants you to talk about the “Polocaust”

Battle lines, by Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon: One battle, two countries and a whole lot of opinions. We talk to people in China and Japan about what they learnt at school about the Nanjing massacre

The empire strikes back, by Andrei Aliaksandrau: Ukraine and Belarus approach their former Soviet status in opposite ways. Plus Stephen Komarnyckyj on why Ukraine needs to not cherry-pick its past

Staging dissent, by Simon Callow: When a British prime minister was not amused by satire, theatre censorship followed. We revisit plays that riled him, 50 years after the abolition of the state censor

Eye of the storm, by Omar Mohammed: The historian known as Mosul Eye on documenting what Isis were trying to destroy

Desert defenders, by Lucia He: An 1870s battle in Argentina saw the murder of thousands of its indigenous people. But that history is being glossed over by the current government

Buried treasures, by David Anderson: Britain’s historians are struggling to access essential archives. Is this down to government inefficiency or something more sinister?

Masters of none, by Bernt Hagtvet: Post-war Germany sets an example of how history can be “mastered”. Poland and Hungary could learn from it

Naming history’s forgotten fighters, by Raymond Joseph: South Africa’s government is setting out to forget some of the alliance who fought against apartheid. Some of them remain in prison

Colombia’s new history test, by Irene Caselli: A new law is making history compulsory in Colombia’s schools. But with most people affected by decades of conflict, will this topic be too hot to handle?

Breaking from the chains of the past, by Audra Diptee: Recounting Caribbean history accurately is hard when many of the documents have been destroyed

Rebels show royal streak, by Layli Foroudi: Some of the Iranian protesters at recent demonstrations held up photos of the former shah. Why?

Checking the history bubble, by Mark Frary: Historians will have to use social media as an essential tool in future research. How will they decide if its information is unreliable or wrong?

Franco’s ghosts, by Silvia Nortes: Many bodies of those killed under Franco’s regime have yet to be recovered and buried. A new movement is making more information public about the period

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: If we don’t support those whose views we dislike as much as those whose views we do, we risk losing free speech for all

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In focus”][vc_column_text]

How gags can remove gags, by Tracey Bagshaw: Comedian Mark Thomas discusses the taboos about stand-up he encountered in a refugee camp in Palestine

Behind our silence, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Refugees feel that they are not allowed to give their views in public in case they upset their new nation, they tell our interviewer

Something wicked this way comes, by Abigail Frymann Rouch: They were banned by the Nazis and now they’re back. An interview with Barry Humphries on his forthcoming Weimar Republic cabaret

Fake news: the global silencer, by Caroline Lees: The term has become a useful weapon in the dictator’s toolkit against the media. Just look at the Philippines

The muzzled truth, by Michael Vatikiotis: The media in south-east Asia face threats from many different angles. It’s hard to report openly, though some try against the odds

Carving out a space for free speech, by Kirsten Han: As journalists in Singapore avoid controversial topics, a new site launches to tackle these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Just hurting, not speaking, by Christie Watson: Rachael Jolley interviews the author about her forthcoming book, why old people are today’s silent community and introduces a short story written exclusively for the magazine

Ban and backlash create a bestseller, by Abbad Yahya: The bestselling Palestinian author talks to Jemimah Steinfeld about why a joke on Yasser Arafat put his life at risk. Also an extract from his latest book, translated into English for the first time

Ultimate escapism, by Mahvesh Sabet: The award-winning poet speaks to Layli Foroudi about fighting adversity in prison. Plus, a poem of Sabet’s published in English for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world, by Danyaal Yasin: Research from Mapping Media Freedom details threats against journalists across Europe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Frightening state, by Jemimah Steinfeld: States are increasing the use of kidnapping to frighten journalists into not reporting stories

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Abuse of History” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F%20|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, Louisa Lim, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99222″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Aug 2017 | Uncategorized

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]From: David Benatar

Subject: TB Davie Memorial Lecture

Date: 02 April 2017 at 12:49:25 AM SAST

To: Mahmood Mamdani

Dear Professor Mamdani

I understand that you are scheduled to give the TB Davie Memorial Lecture this year. This named lecture, as you know, is devoted to the theme of academic freedom and freedom more generally. What you might not know is that the 2016 lecture was going to be given by Mr. Flemming Rose, cultural editor of the Jyllands-Posten newspaper and notable defender of freedom of expression. However, the University Executive, over the protestations of the then-members of the Academic Freedom Committee disinvited Mr Rose because they perceived him as a controversial speaker. I responded to this ironic and outrageous breach of academic freedom here: http://www.politicsweb.co.za/opinion/uct-a-blow-against-academic-freedom

The Academic Freedom Committee’s term of office came to an end at around this time and the new committee has invited you to be the speaker in 2017. While it is possible that you might use the opportunity of the TB Davie lecture to criticise the University for having disinvited Mr Rose, it would be far more effective if you and other potential speakers in future years refused to give the lecture. Until Mr Rose’s disinvitation is reversed, the TB Davie lecture will be a farce. Thus I urge you to indicate to the Academic Freedom Committee that you will not deliver a TB Davie lecture until Mr Rose has been allowed to deliver the lecture he was invited to give.

Yours sincerely,

David Benatar[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1501498075189-5ba0ae4f-e1a9-10″ taxonomies=”16315, 4524, 8562″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]