Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

This week, UN officials described the Syrian regime’s offensive against the besieged city of Aleppo as “barbaric”. Following the collapse of a short-lived ceasefire, Syrian forces again began bombing Aleppo on Sunday, a continuation of the “unrelenting onslaught of cruelty”.

Aleppo is the former home of Zaina Erhaim, activist, journalist and winner of the 2016 Index on Censorship award for journalism for her work training citizen journalists to report on the conflict within the city.

2016 Freedom of Expression Fellow Zaina ErhaimZaina Erhaim is the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winner and fellow. A Syrian native who was studying journalism in London when war broke out in Syria in 2013, Erhaim decided to return permanently to report and train citizen journalists in the war-ravaged country. Read more about Erhaim’s work. |

The battle for Aleppo has been raging since 2012, the same year Erhaim’s husband, the activist Mahmoud Rashwani, was arrested and tortured by the Syrian regime for participating in peaceful protests.

Writing on 11 August 2016 Erhaim – who now lives in Turkey with the couple’s seven-month-old daughter – said: “Among the estimated 300,000 to 400,000 people living on Aleppo’s eastside, Mahmoud hadn’t had any vegetables or fruit for the past month.”

She added that shortages of food – from fresh produce and canned food, to eggs, flour and baby milk – along with a lack of fuel have have left the people of Aleppo increasingly vulnerable.

Speaking to Index on Censorship, Erhaim said she was “incredibly proud” about her husband’s “brave” work searching for survivors among the rubble of bomb out buildings in Aleppo alongside other volunteers.

On 15 August, it was Rashwani’s neighbour’s home which was left in ruins. The neighbour – a journalist – along with his pregnant wife, were killed, while Rashwani escaped with a knee injury, Erhaim told Index.

Rashwani’s home, which he shared with Erhaim before she left the city, was also damaged.

My house this morning after a barrel bomb attack that hit my neighbour last night. #Aleppo #Syria pic.twitter.com/49Q5v1EnWL

— Mahmoud Rashwani (@MahmoudRashwani) August 16, 2016

Rashwani travels between Syria and Turkey to be with his family, but the journey has become increasingly difficult as the war rages on, Erhaim said.

Erhaim herself faced difficulty with a border this week. Travelling from Istanbul on 22 September to attend an event organised by Index on Censorship, border officials at Heathrow airport held the activist and her child for an hour before confiscating her passport after it was reported by the Syrian authorities as stolen. She was told that her passport would have to be returned to the Syrian government.

Thank u #FriendsOfTyrant ! #Syria|n activist barred from travel after #UK seizes passport at Assad’s request https://t.co/synEC0KFdI

— Zaina Erhaim (@ZainaErhaim) September 25, 2016

Erhaim was able to enter the UK on an old passport. However, this passport is now full, making future travel plans and visa applications potentially impossible.

Now back in Turkey, she will continue to work on projects with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, she told Index. She is in the process of selecting five activists for a filmmaking project and has just completed hostile environments, first aid and digital security training with a number of journalists – essential skills for anyone reporting from Syria.

Erhaim will also continue to work on the Women’s Blog on The Damascus Bureau, which has just received a book deal from a French publisher. “The first edition will be in French and will be followed by editions in Arabic and English,” she told Index.

Speaking ahead of the Index event on women who report from war zones, Erhaim told Index: “The voices of women are very important because they are telling what is happening behind the frontline. While the major concern for most of the men in these situations is the actual conflict, women also think about education, health systems, clinics, social traditions, the changes in wedding styles – they are reporting on life.”

Nominations are now open for 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards and will remain open until 11 October. You can make yours here.

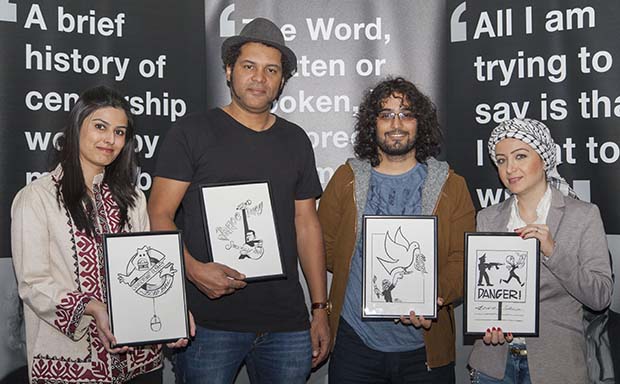

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

More about Zaina Erhaim

Index condemns UK’s seizure of award winner’s passport

Women on the front line: Zaina Erhaim and Kate Adie on the challenges of war reporting

Zaina Erhaim: “I want to give this award to the Syrians who are being terrorised”

#IndexAwards2016: Zaina Erhaim trains Syrian women to report on the war

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship is appalled by the decision of UK border officials to confiscate the passport of Syrian journalist, Zaina Erhaim. The Syria coordinator for the Institute of War and Peace Reporting, Erhaim has been recognised by a number of organisations internationally for her work training citizen journalists to report on the conflict within Aleppo.

Index invited Erhaim, in her capacity as winner of this year’s Freedom of Expression Awards, to an event at Write on Kew Festival to speak about her experiences alongside veteran journalist Kate Adie.

When Erhaim arrived in the UK on Thursday 22 September for the event she was detained by the UK Border Agency (UKBA) and questioned for an hour before UKBA confiscated her passport. Erhaim was told that the passport had been reported by the Syrian authorities as stolen and therefore UKBA was compelled to retain it and return it to the Syrian government.

Erhaim had her old passport, which remains valid but is effectively unusable because the pages are filled, and was able to enter the UK for the debate. Further travel may be impossible, however, as Erhaim no longer has a passport with which to apply for a new visa to enter Europe.

When Erhaim challenged this decision, she was told to seek consular advice from the Syrian government in Damascus.

“We are extremely disappointed by the treatment of Zaina by border officials. It seems quite astonishing that the UK would accede to a request from a government whom it has only this weekend accused of being complicit in war crimes – especially when it is clear that the Syrian government is using tools, such as passport rescindments, to harass those who oppose or expose its behaviour,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

Index will be raising the matter with the Home Office and Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

If you would like to write a letter in support of Zaina Erhaim, address your correspondence to:

Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP

Secretary of State for the Home Department

Direct Communications Unit

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP

Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

King Charles Street

London

SW1A 2AH

More about Zaina Erhaim

Women on the front line: Zaina Erhaim and Kate Adie on the challenges of war reporting

Zaina Erhaim: “I want to give this award to the Syrians who are being terrorised”

#IndexAwards2016: Zaina Erhaim trains Syrian women to report on the war

The family of murdered journalist and Sunday Times correspondent Marie Colvin has filed a lawsuit against the Syrian government, accusing it of being responsible for her death while she was reporting in the country in 2012.

The suit, filed to a federal court in Washington, alleges that Colvin was killed in a deliberate attack, planned by President Bashar al-Assad’s government, to silence the media “as part of its effort to crush political opposition”.

Colvin, a veteran war reporter, was killed alongside French photojournalist Remi Ochlik when a rocket attack was launched against a makeshift broadcast studio in the rebel-controlled area of Baba Amr in Homs, the country’s third city.

Colvin’s work and legacy is discussed in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which has a special report on the risks of reporting worldwide. In a piece debating whether journalists should work in war zones, Channel 4 New’s Lindsey Hilsum writes: “In February 2012, Marie and photographer Paul Conroy crawled through a sewer to get to Homs, as the Syrian regime’s bombs turned the buildings of rebel-controlled Baba Amr to burnt-out carcasses and rubble. In her dispatches, Marie described the makeshift beds on which children slept underground to avoid the bombs, the operations without anaesthetic, the despair of people who felt they had been abandoned by the world. It was classic, old-fashioned eyewitness reporting […]

“Marie felt she had a responsibility to report; she refused to leave it to YouTube. Yet, on this occasion, the risk was too great. Was she brave, or – in her own words – was it bravado? Either way, we are all the poorer because Marie Colvin is no longer reporting from Syria.”

Read the full piece in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

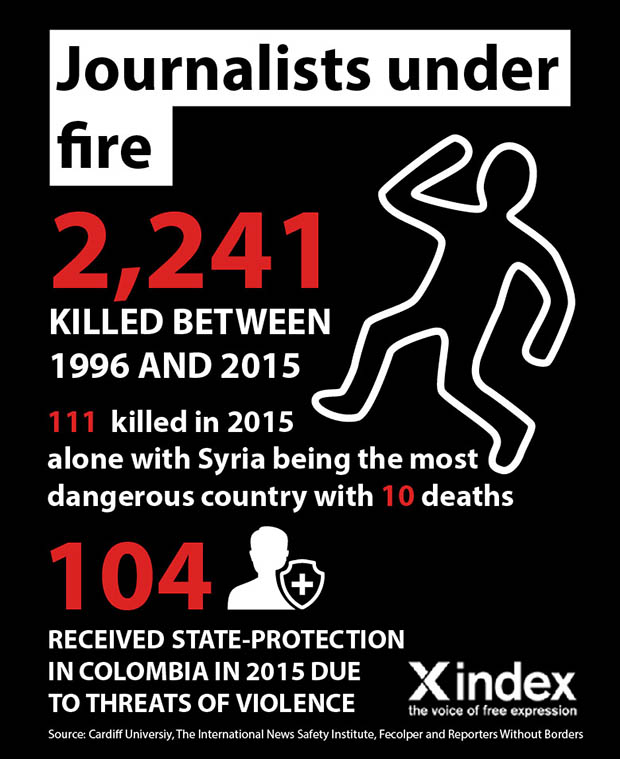

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]