9 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Previo a publicación de un nuevo informe sobre las amenazas a los medios de comunicación en el país, Rhodri Davies habla con los sirios que crearon su propia emisora de radio”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Varios locutores de la emisora SouriaLi, reunidos con invitados en Amán (Jordania), SouriLa

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«Compramos unos trapos muy gruesos para fabricar una especie de insonorización; así nuestras voces no se oirían desde fuera y el sonido de las bombas no entraría al apartamento», cuenta el periodista Dima Kalayi, describiendo cómo un grupo de personas unió sus fuerzas en un piso diminuto y comenzó a realizar programas para una emisora independiente siria. El piso de Damasco fue el primer lugar en el que pudieron reunir a gran parte del equipo de la nueva emisora.

«Queríamos que SouriaLi fuera un ejemplo de cómo nos gustaría que [fuera] Siria en el futuro», dice Caroline Ayub, una de los cuatro cofundadores de la emisora, que ayudó a montarlo todo desde el exilio. Ayub explica que querían mostrar la identidad diversa de Siria, al mismo tiempo que recordaban también la cultura que todos tienen en común. Por otro lado, les daba la sensación de que se recurría demasiado a los medios internacionales para informarse sobre su propio país.

«Para nosotros, el objetivo principal de la revolución era expresar la propia voz e identidad. Y para ello es esencial hacer que esa voz continúe», añade Ayub, que huyó a Marsella tras haber estado presa durante un mes en 2012 por distribuir huevos de Pascua con citas sacadas de la Biblia, junto a otras del Corán (las autoridades la acusaron de terrorismo).

SouriaLi, que puede traducirse como «Siria es mía», transmite las 24 horas y cuenta con podcasts, contenido visual y una app. Sin embargo, no compite contra los programas de noticias duras a tiempo real. La intención de la emisora es reflejar los problemas que sufre el país por medio de debates y tertulias —interactuando en vivo con el público por WhatsApp y Skype regularmente—, así como radionovelas y cuentacuentos.

Lo suyo es verdadera vocación. El informe del Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas, cuya publicación está prevista para noviembre, hará mención a la creciente gravedad de la situación de los periodistas sirios y espera que el país pase de estar en tercer lugar a ser la segunda nación más peligrosa en su índice global.

SouriaLi se vale de periodistas para recabar información, que luego contrasta con otras fuentes. Al contar con miembros provenientes de una amplia área geográfica dentro del país —aunque la mayoría viven ahora en el exilio—, su red de contactos en Siria es “extensa”, según Iyad Kalas, otro cofundador y director de programación. Explica que siempre examinan la procedencia de las fuentes y el modo en el que se ha obtenido la información para poder establecer su nivel de credibilidad.

Su serie semanal titulada Yadayel (“Trenzas”) cuenta historias de mujeres, como el trato que reciben en puestos de control, la experiencia de vivir en Raqa bajo el control del EI o cómo es trabajar en un hospital.

«Es muy importante para nosotras, porque así estás dándoles voz [a] las mujeres. La mayoría de estas mujeres provienen de una sociedad muy oprimida y conservadora», explica Ayub.

Llegó a haber 11 personas de la emisora en Siria, más las que trabajaban desde fuera. Hoy, sin embargo, solo queda un miembro del equipo en el país: muchos de ellos acabaron en la cárcel antes de marcharse de Siria, algunos por oponerse al gobierno y otros por enviar ayuda. La mayoría de los que no fueron arrestados, como Kalayi, que vive en Berlín desde 2013, abandonaron el país. Ayub describe SouriaLi como «un medio exiliado porque, por el momento, estamos en el exilio».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

El equipo ahora suma 27 miembros, voluntarios incluidos, que trabajan desde 14 países distintos de Oriente Medio, Europa y Norteamérica.

La labor de reafirmar la diversidad de Siria supone facilitar el acceso a las ondas a todas las voces del grupo, ya sean kurdas, suníes, chiíes, alauíes, armenias, cristianas o de otro tipo. Kalayi produjo una serie titulada Fatush, en la que tomaba recetas típicas de las diferentes regiones y grupos de Siria y hablaba sobre identidad étnica y problemas a menudo ignorados, mano a mano con la gastronomía.

SouriaLi trata de incluir una variedad de perspectivas, aunque las figuras prorrégimen raras veces aceptan la invitación. Pese a todo, la emisora ofrece la oportunidad de expresarse a todos los puntos de vista. «Creemos firmemente que los medios de comunicación, como una emisora de radio, una plataforma, deberían ser para todos los sirios», afirma Ayub.

Sus emisiones atraen a un público numeroso: tienen más de 450.000 seguidores en Facebook. La emisora solía emitir en FM en 12 zonas de Siria, en las que compañeros locales se encargaban de la transmisión. Sin embargo, el régimen de Assad siempre prohibía la emisión en las regiones que caían bajo su dominio, y diferentes grupos de combate de la oposición, como Yabhat al Nusra (entonces vinculado con Al Qaeda, hoy rebautizado como Yabhat Fateh al Sham), han tratado de controlar el contenido de SouriaLi. Exigían, por ejemplo, que dejasen de emitir ciertos programas y música, como el contenido kurdo, o los obligaban a emitir el Corán. La emisora también recibió amenazas del Estado Islámico.

SouriaLi se negó a recibir órdenes del gobierno o de sus oponentes, y puso fin a su transmisión en FM a mediados de 2016. «Así que decidimos dejarlo», relata Ayub. «Dijimos: “Siria ya no es [solo] Siria de la frontera adentro. Siria es todos los sirios de cualquier lugar.” Tenemos millones de sirios fuera, en Europa. Todos necesitan la esperanza, la información que estamos emitiendo, así que recalibramos nuestro centro atención».

La emisora de radio pasó a ser solo en línea. Su página web está disponible para la población siria, tanto en los lugares donde no hay censura como a través de VPN. También hay una versión pensada para evitar la censura que solo incluye la emisión de radio en directo.

Kalas, que abandonó Siria por Francia en 2012, cuenta que ahora la emisora podría pasar a estar solo en internet, pues «Siria es un país virtual» con oyentes repartidos por todos los puntos del globo. SouriaLi calcula que alrededor del 40% de su audiencia online está ubicada en Siria, otro 40% lo forma su diáspora y otro 18% son oyentes de habla árabe, principalmente de Irak y Egipto.

Mantener la moral alta es uno de los mayores retos a los que se enfrenta el equipo, según Kalas y Ayub. «Antes de 2011 no había realmente “medios” o “periodismo” en Siria», apunta Kalayi. Ahora, se siente optimista. «Tengo libertad para elegir los temas, cómo tratarlos, cómo presentarlos. Y esto es algo muy importante para mí como persona y como periodista». Y cuando las condiciones lo permitan, quiere volver a Siria y seguir haciendo eso mismo.

Ayub añade: «Yo creo que a un país [como] Siria le hacen falta miles y miles de proyectos de comunicación, muchas plataformas para que la gente se exprese, para debatir. Porque, sin debate, sin libertad de expresión, nunca existirá un país libre. Y esto, por supuesto, es aplicable a Siria también».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rhodri Davies es periodista independiente. Ha escrito reportajes desde Catar, Egipto, Irak y Yemen.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en otoño de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Russian

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Накануне нового доклада об угрозах для сирийских СМИ, Родри Дэвис переговорил с сирийцами, создавшими собственную радиостанцию”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Некоторые из ведущих на радиостанции CурияЛа, с гостями, на встрече в Аммане, Иордания, SouriLi

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«Мы купили очень плотную одежду для хоть какой-то звукоизоляции; чтоб снаружи не было слышно наших голосов, и чтобы не было слышно взрывов внутри квартиры», — сказал журналист Дима Каладжи. Он описал, как команда собралась вместе в маленькой квартирке, чтобы выпускать программы для независимой сирийской радиостанции.

Квартира в Дамаске была первым местом, где они могли объединить многих сотрудников новой радиостанции. «Мы хотели, чтобы СурияЛи была примером Сирии в будущем», —сказала Каролайн Айюб, одна из четырех основателей станции, которая помогла установить её будучи в изгнании. Они хотели продемонстрировать многообразие обычаев и традиций Сирии и в тоже время, напомнить людям о культуре, которая их объединяет. Они также считали, что был высокий уровень доверия к международным СМИ как источнику новостей о своей собственной стране.

«Возможность свободно выражать своё мнение и проявлять свою личность для нас была главной целью революции. И этот голос по-прежнему важен», — сказала Айюб, которая сбежала в Марсель после месячного заключения в 2012 году за распространение пасхальных яиц вместе со словами из Библии и Корана (власти обвинили её в террористической деятельности).

СурияЛи, что переводится как «Моя Сирия», которая ведёт прямую трансляцию 24 часа в сутки, выкладывает подкасты, видео и приложения, не конкурирует с жесткими оперативными новостями. Вместо этого станция отображает проблемы в Сирии путем дебатов и ток-шоу – регулярно взаимодействует с аудиторий на Вотсапп и Скайп, плюс включает драмы и повествования.

Их работа не проста. Комитет по защите журналистов сделал доклад, который должен выйти в ноябре. Он признает, что ситуация сирийских журналистов ухудшается. Комитет планирует перенести Сирию из третьего места на второе из худших наций в глобальном индексе.

СурияЛи собирает информацию от журналистов, проверенную ссылками с других источников. Изначально было много сотрудников со всех географических уголков страны, но теперь они в основном в изгнании. Сеть контактов СурияЛи в Сирии «огромная», делится Ияд Каллас, другой соучредитель и директор программирования. Он добавляет, что они всегда изучают откуда поступает информация и как её собрали для того, чтобы удостовериться в надежности источника.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Еженедельная серия Джадайель («Косички») рассказывает истории женщин: как к ним относятся в контрольно-пропускном пункте, об их опыте жизни в контролируемой ИГИЛ Раккой и работе в больнице.

«Для нас это очень важно. Вы даете возможность услышать голос женщин. Большинство этих женщин – выходцы из очень угнетённого или консервативного общества», — сказала Айюб.

В одно время на станции в Сирии работало 11 человек, другие трудились заграницей. Сегодня в стране остался только один сотрудник. Многие попали в тюрьму уезжая из Сирии – одни за сопротивление правительству, другие за доставки помощи. Большинство избежавших ареста, включая Каладжи, который живёт в Берлине с 2013 года, покинули страну. Айюб описала СурияЛи как «СМИ в ссылке, потому что мы временно изгнаны».

Сегодня в общей сложности насчитывается 27 сотрудников, в том числе добровольцев, работающих на станции из 14 стран, стран Ближнего Востока, Европы и Северной Америки. Акцентирование разнообразия Сирии требует эфирного времени для выражения точки зрения групп

курдов, суннитов, шиитов, алавитов, армян, христиан и других. Каладжи выпустила серию под названием Фатуш. Она готовит блюда по рецептам из разных регионов Сирии, обсуждая этническую специфику, проблемы маргинализации и еду.

СурияЛи стремится представлять различные точки зрения, хотя редко кто из провластных личностей принимает приглашение. Тем не менее, радиостанция предоставляет возможность всем сторонам выразить себя. «Мы действительно верим в то, что СМИ, радиостанции, платформы, должны быть для всех сирийцев», — сказала Айюб.

Их передачи привлекают широкую аудиторию, более чем 450 000 человек следят за СурияЛи на Фейсбуке. Станция раньше вела вещание на 12 FM каналах в Сирии, с партнерами на местах, которые обеспечивали вещание. Режим Асада будет всегда запрещать радиовещание в своих регионах, хотя и различные оппозиционные группы, в том числе Джабат аль- Нусра (который раньше связывали с «Аль-Каида», а теперь группа переименовалась на Джаб-хат Фатех аль Шам), пытались контролировать содержание СурияЛи. Они требовали прекратить вещание некоторых программ и музыки, например, программ про курдов или принуждали трансляцию Корана. Станции также угрожал ИГИЛ.

СурияЛи отвергла требования правительства и его противников. Она приостановила вещание в середине 2016. «Мы решили закрыться», — сказала Айюб. «Мы сказали: ‘ У Сирии больше нет границ. Сирийцы – и есть Сирия, где бы они не были ‘. Миллионы соотечественников живут за пределами Европы. Им всем нужна надежда, новости, которые мы транслируем. И мы поменяли свое направление”.

Радиостанция перешла исключительно в онлайн режим. Её веб-сайт доступен для людей в Сирии, где нет никакой цензуры или через VPN. Существует также версия, направленная на обход цензуры с прямым эфиром.

Каллас, который покинул Сирию в 2012 году и уехал в Францию, говорит, что станция может перейти в онлайн режим только теперь, так как «Сирия является виртуальной страной», её слушатели разбрелись по всему миру.

Около 40% её онлайн аудитории находится в Сирии, 40% – диаспора сирийцев и 18% арабоязычная аудитория, главным образом из Ирака и Египта. Моральный дух персонала является одной из крупнейших проблем, согласно Каллас и Айюб. «До 2011 года в Сирии не было настоящего «СМИ» или «журнализма»», — сказала Каладжи. Теперь она верит в будущее. «Я сама могу выбирать темы, сама выбираю, как с ними работать и как их представлять. Это очень важно для меня как человека и журналиста.» Когда позволят обстоятельства, она так же хотела бы заниматься этим в Сирии.

Айюб сказала: «Я верю, что такая страна [как] Сирия нуждается в тысячах и тысячах медиа-проектах, платформах для людей, чтобы они могли себя выразить». Потому что без обсуждения, без свободы слова, никогда не будет свободной страны. И это, конечно, относится и к Сирии.»

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Родри Дэвис является внештатным журналистом, который докладывает из Катара, Египта, Ирака и Йемена

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to Air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Sep 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Syria, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Syrian journalists Orouba Barakat and her daughter Halla Barakat were found murdered in Istanbul. (Facebook)

The bodies of Syrian journalists Orouba Barakat and her daughter Halla Barakat were discovered in their apartment in Istanbul late Thursday 22 September, 2017.

Friends who failed to reach Halla Barakat by phone called the police, who had a locksmith open the apartment located on Yangaç Street in the Üsküdar neighbourhood.

According to police reports, the Barakats were strangled and then stabbed. The perpetrators also poured detergent powder on the bodies to minimise the smell of the decomposing bodies.

“The brutal killing of Orouba and Halla is a tragedy for press freedom.” Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom, said. “As we mourn the loss of two brave journalists, we call on the authorities to swiftly investigate and identify those responsible for this heinous crime.”

Orouba Barakat was a journalist, filmmaker and activist who was an outspoken critic of the Assad regime and a staunch supporter of the revolution. She had exposed countless atrocities of the Assad regime in prisons.

Her daughter Halla (22) was a reporter for Alekhbarya TV, news editor for the Orient and former editor at Turkish state channel TRT world.

Both Barakat and her daughter had been reportedly receiving threats from groups associated with the Bashar Assad government.

Orouba Barakat was forced to spend most of her life in exile. She fled her native Syria in the 1980s. She resided in the UAE before moving to Istanbul.

The police are still investigating the murder. The date of the murder is not yet known.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_custom_heading text=”Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fpress-regulation%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors media freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 22/9/2017, there were 525 verified violations of press freedom associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists. Support our work today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506088588004-59d922a2-300c-5″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Aug 2017 | Awards, News and features, Syria

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”95161″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/GUWv8_bOXgg”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award-winning Bassel Khartabil, a Syrian-born Palestinian digital activist, worked to build a career in software and web development. Before his arrest in 2012, he used his technical expertise to help advance freedom of speech and access to information in Syria via the internet. His execution by the Syrian government in 2015 was announced by his wife, Noura Ghazi Safadi, on Tuesday 1 August 2017.

The following speech was delivered at the 2013 Freedom of Expression Awards by his friend and colleague Dana Trometer.

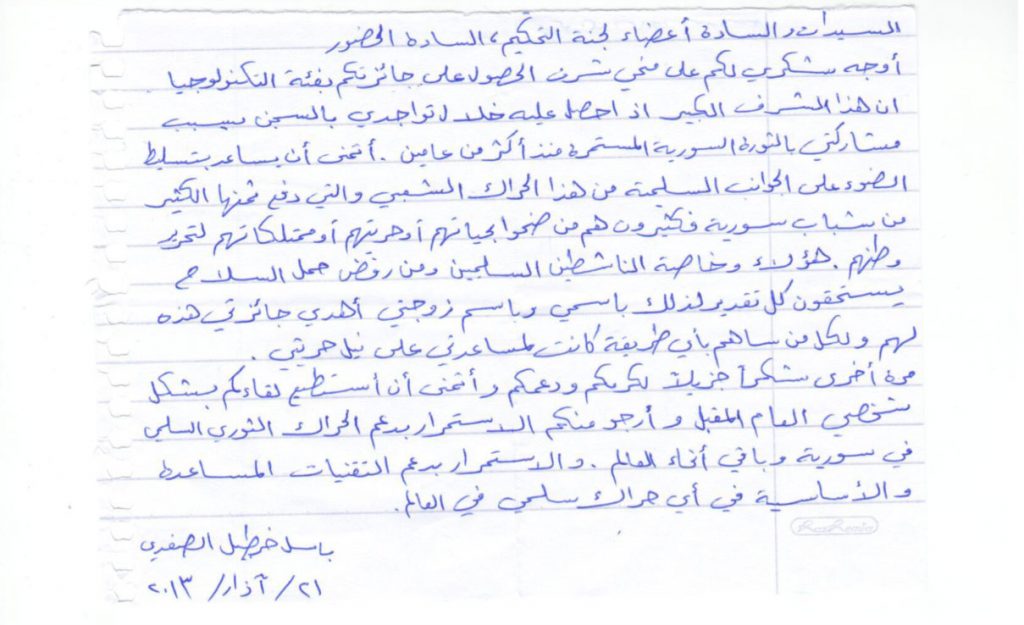

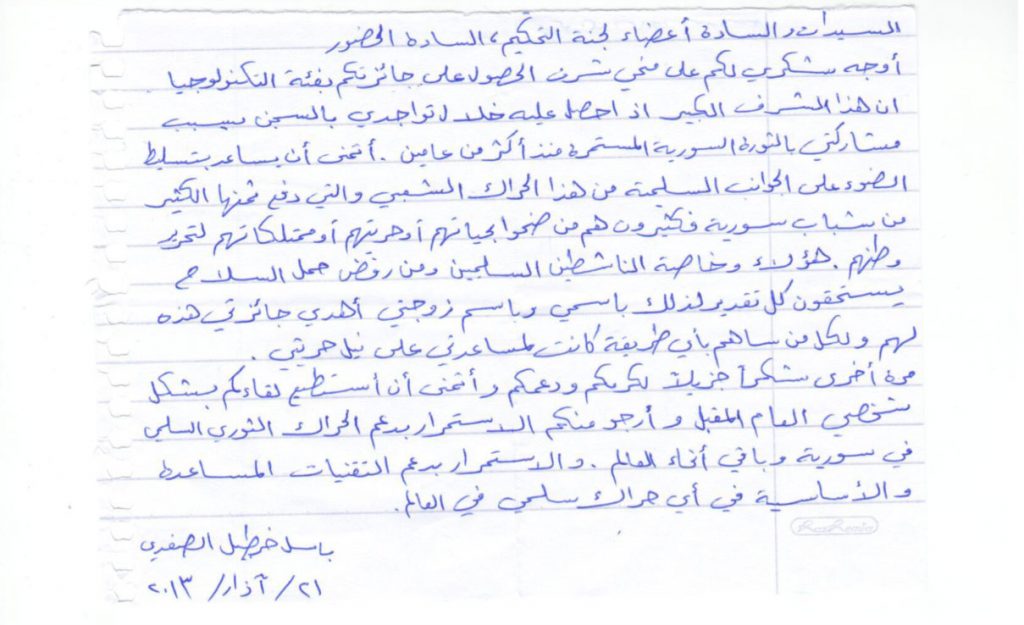

Dear Prize Jury Committee Members, Dear Madams and Sirs,

I would like to thank you for this award. I am truly honoured to receive it.

I hope, this great honour, that I receive while I am still in prison for participating in the Syrian Revolution that has been going two years, will shed a light on the nonviolent sides of this popular movement that has claimed the lives of many young Syrian men and women.

Many are those who have lost their possessions, faced imprisonment or sacrificed their souls for freedom in Syria. Those, especially nonviolent activists, who refused to carry arms, deserve all the credit and respect.

Therefore in my name and the name of my wife, I dedicate this award to them, and to all those who are helping me win my freedom back.

I would like to thank you again for your support and for your generosity and I hope I will be able to meet you in person next year, and I urge you to support nonviolent activism and to continue to provide nonviolent movements with the essential technical support in Syria and around the world.

Bassel Khartabil Al Safadi

In prison when he received the 2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award, Bassel Khartabil wrote his speech to be delivered by a colleague in the UK.

Bassel Khartabil, winner of the 2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award, was in prison when he won the award. His friends accepted the award on his behalf. From left: Jon Phillips, Dana Trometer and then-chair of Index on Censorship Jonathan Dimbleby.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502980043124-10539406-bf4f-4″ taxonomies=”5407″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]