17 Jul 2020 | Index Shots, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]On 5 July 2017, human rights defenders from a number of different organisations gathered on the island of Büyükada for a workshop on the protection of digital information.

On the third day of the workshop, ten of the attendees were arrested at gunpoint and later charged with aiding the Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organization, which President Erdoğan blames for 2016’s failed military coup.

The Istanbul 10, as they became known, were released on bail on October 25th 2017, after 113 days in detention but then faced three years of court hearings.

On 3 July 2020, former Amnesty Turkey chair Taner Kılıç was convicted of membership of the Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organization and sentenced to 6 years 3 months in prison.

Meanwhile, Özlem Dalkıran, İdil Eser and Günal Kurşun were convicted of assisting the organization and sentenced to 25 months, pending an appeals process which could last years.

As the sentences were announced, Index’s editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley spoke with Özlem Dalkıran.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/jFAojAdwiQk”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Jun 2020 | News, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Richard Patterson/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

“Tracking apps”, “social distancing”, “quarantine” – all terms that have dominated the 2020 news cycle so far (remember when it was just about Brexit and Donald Trump?). But how much do you actually know about tracking apps after months of them making headlines? And as for drones, you’ve heard they’re checking up on us, but do you know how many the British police have in their fleet?

Take our quiz based on the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Private Lives, to find out the answers to these questions, and more.

[streamquiz id=”6″][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Jun 2020 | Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

The summer 2020 edition of the Index on Censorship podcast looks at just how much of our privacy might we give away – accidentally, on purpose or through force – in the battle against Covid-19.

The podcast also features the world premiere of a lockdown playlet written exclusively for Index on

Censorship by Katherine Parkinson. Parkinson, best known for her role as Jen Barber in The IT Crowd, also stars as Sarah in the play, alongside actors Harry Peacock and Selina Cadell.

Arturo di Corinto speaks on the podcast about technological terms that have been used more and more in the crisis while Emma Briant discusses around techniques world leaders are using in the run-up to elections to stifle opposition.

Print copies of the magazine are available via print subscription or digital subscription through Exact Editions. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

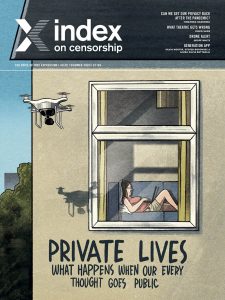

17 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][vc_column_text]

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what’s around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don’t just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy’s bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary’s media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties – personal and professional – of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question