Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Hundreds of Ugandans took to the streets in support of the government’s proposed anti-homosexuality bill in 2009 (Image: Edward Echwalu/Demotix)

A petition has been filed to the Constitutional Court of Uganda seeking to repeal the Anti Homosexuality Act 2014, on the grounds that it is “draconian” and “unconstitutional”.

The petitioners — MP Fox Odoi, Joe Oloka Onyango, Andrew Mwenda, Ogenga Latigo, Paul Semugooma, Jacqueline Kasha, Julian Onziema, Frank Mugisha and two civil society organisations — are challenging sections 1, 2 and 4 of the recently passed anti-gay law, which criminalise homosexual activity, between consenting adults in private. They argue these sections are in contravention of the right to privacy and equality before the law without discrimination, guaranteed under the Ugandan constitution. They also claim the that bill was passed without quorum in parliament, despite Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi informing the speaker of this — also an unconstitutional act.

Addressing the media after filing the petition, Odoi vowed to fight for the rights of gay people even if it meant him losing support from his constituency. “I would rather lose my seat in parliament than leave the rights of the minorities to be trampled upon. I don’t fear losing an election, but I fear living in a society that has no room for minorities,” he said. “A country that cannot tolerate minority groups like gays should never claim to be democratic, lawful and pro-people,” he added.

The petitioners have highlighted several parts of the new law that they believe to be unconstitutional. They argue that life sentence for homosexuality is in contravention of the freedom from cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment, while the section subjecting persons charged with “aggravated homosexuality” to compulsory HIV test is inconsistent with a number of articles in the constitution.

The petition also argues that through banning aiding, abetting, counselling, procuring and promotion of homosexuality, the law is creating overly broad offences. Additionally, the group state that it’s wrong for the act to penalise legitimate debate on homosexuality, as well as professional counsel, HIV-related service provision and access to general health services for gay people.

Petitioner Ogenga Latigo, former leader of the opposition in parliament, questioned the competence of the speaker of parliament who passed the law without quorum. Speaker Rebecca Kadaga has in the past been vocal about her disdain for homosexuals, and wanted this law passed before the end of 2012 as a “Christmas gift” to Ugandans. “The speaker’s position should always remain neutral while tabling issues in parliament, but our speaker went on and enforced her views on all MPs; the speaker never followed the procedures that govern the passing of laws in parliament because of her homophobic beliefs,” he said.

The group argues that since the law was enacted, there has been an increase in the number of violent attacks on gay people. In other instances, they say, those suspected or known to be gay have been evicted from their apartments by homophobic landlords.

Odoi, who authored a minority report against the bill before it was passed by parliament, is optimistic that the petition will succeed, if the case is handled by unbiased judges. “We want court to declare the law unconstitutional, null and void and cease to be a binding law, thus give a chance to homosexuals to enjoy their rights and freedoms,” he asserted.

This article was posted on March 14 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

British theatre producer David Cecil brought worldwide attention to Uganda’s homophobic criminal code after he was arrested and charged for producing a “pro-gay” play in the country.

The Anti-Homosexuality Bill, a version of which was first introduced in 2009, was passed just before Christmas and signed by President Museveni at the end of February, meaning certain homosexual acts are now punishable with life in prison in Uganda.

The River and The Mountain tells the story of a successful young businessman who is killed by his employees after coming out as gay. Cecil was arrested in September 2012, when his theatre company refused to halt its production pending a content review by the Ugandan Media Council, and staged two performances in Kampala. The Council later deemed the play to be promoting homosexuality. Cecil spent four nights in a maximum-security prison and faced a two-year prison sentence or deportation if convicted.

The case attracted media attention both in Uganda and abroad, and Index on Censorship and David Lan, the artistic director of the Young Vic, launched a petition calling for the charges against Cecil to be dropped. It was signed by more than 2,500 people, including director Mike Leigh, Stephen Fry, Sandi Toksvig and actor Simon Callow, bringing attention to the wider issue of gay rights and freedom of expression in Uganda.

The charges were finally dropped on 2 January 2013, as the prosecution had failed to disclose any evidence. However, Cecil was re-arrested in February, spent five nights in prison, and was finally deported on the grounds that he was an “undesirable person”.

Cecil was deported from Uganda as a result of his play. He has been nominated for the Index Freedom of Expression Arts Award and spoke with Alice Kirkland about what this means to him.

Index: How does it feel to be nominated for the Index on Censorship arts award and why do you think you have been nominated?

David: The honour is bittersweet, as I am unable to continue living in Uganda because of what I did; the last year has been fraught with anxiety and uncertainty. Since meeting your representatives in early 2013, I stumbled across a load of back issues of your magazine from the 1980s. Reading through articles by Umberto Eco and Ronald Dworkin made me feel part of something bigger, a story unfolding over time.

I believe I was nominated because we were perceived as standing up for gay rights in a country where it’s hard to talk about homosexuality publicly. To me, at the time, we were just putting on a play and had little idea of how much impact it would have.

Index: You spent time in prison in Uganda for your part in the production of the “pro-gay” play The River and The Mountain. What impact has this had on your work and life since the incident? Would you or have you produced a play since on the same topic in a country that implements homophobic laws?

David: Since February 2013, I’ve been living in the UK as a deportee from Uganda, where I had spent 6 years building a career and a life with my new family (girlfriend and 2 kids, all Ugandan). With the recent (February 2014) signing of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill into law, plus other sinister developments, I now have to accept that Uganda is no longer safe for me and my family. So that chapter in my life is now closed and my family are now finally joining me here in London. This is a huge blow.

One colossal irony in all of this is that our play was not actually “pro-gay”. It simply portrayed a gay character sympathetically and satirised the politicisation of sexuality in Uganda. The people who targeted us have done all the work of promoting awareness of homosexual issues in their country.

Gay issues and rights are no obsession of mine. So, if I ever do tackle this subject again, it will be coincidental; I am primarily interested in the quality of a script or the enthusiasm of a moment.

Index: By having your production shut down, spending time in jail and facing a criminal trial you obviously had your right to free speech quashed. How did this make you feel?

David: Excited, then bemused, then frustrated, then furious, now a bit depressed – the latter mainly about Uganda, my erstwhile adopted country.

Ugandan prison was very relaxing and even pleasant. Initially, I was in the section for remand prisoners, short sentences and white-collar crime. The people were friendly, relaxed and understanding. Later, I was locked up for a week in a crowded, rough police station. That had its interesting moments, such as ghost-story-telling by candle-light, and a brilliant cast of characters. I rose to become “resident police” (prison boss) by slapping a Fagin-type with a flipflop.

My feelings are less important. I am not the victim in this story. The ones suffering are my family, and the Ugandan people.

Index: Can you explain about the run up to the production of the play in Uganda? Were you aware before the opening night that running the show could land you in jail?

David: It is important to note that the original genesis of the play comes from a meeting with a local theatre group, Rafiki. They, a group of young, heterosexual Ugandan actors and actresses, wanted to produce a play on the theme of “homosexuality”. I agreed to help, as long as it would be a comedy. Coincidentally, a friend of a friend was visiting from the UK at the time; this was Beau Hopkins, a poet and playwright, who agreed to work on the script according to a story developed in a collaborative workshop. Angella Emurwon, an award-winning Ugandan playwright, agreed to direct. It is important to note also that all the Ugandans involved are religious; one of them describes himself as a “devout Christian”.

Fast forward 4 months. I was told a week before the press premiere night that we needed to get special clearance from the Ugandan Media Council (UMC). I had already tried to secure this three months before and was told it was not necessary. (The junior UMC worker who told me this was correct; normally, one would not have to get any clearance for a theatre play in Uganda.) In the end, the secretary of the UMC decided to politicise what we were doing and, at the very last minute, insisted that I sign a letter asking us to desist until they had reviewed the script with their 11-strong committee. Pius, the secretary knew that this meant the play would not be performed, due to subsequent commitments of the director and the key actors, as I had already informed him of all that. The letter was cc-ed to the prime minister’s office, the chief of police, the head of media crimes CID and the minister of ethics & integrity. Because the letter made no mention of legal consequences, articles or anything binding, I signed.

I immediately visited a friend of mine, a human rights lawyer, Godwin Buwa, whose prognosis proved remarkably accurate in all but one regard. The letter was indeed a threat – it could not stand up in a court of law – however, one of the agencies cc-ed may try and act on it. I could be charged with something, possibly, but since the letter was so badly phrased, the worst I would suffer would be a few nights on remand. Since the case would have no water, I would be guilty of no crime and would not be deported.

We had a meeting with the cast. My name was on the paper, they were not in danger. We had worked too hard to be bullied into silence by a badly-phrased letter. We agreed to go ahead and face the consequences.

Perhaps I carried over an element of bravado from my experiences organising underground raves and music festivals in Europe, sometimes in the teeth of official sanction. At worst we had our sound system seized and threatened on numerous occasions, but always continued doing what we loved doing.

Index: Your trial brought global media attention to the situation in Uganda regarding the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, but did this attention do anything to change the laws in the country?

David: To make a faintly disgusting analogy, I think that much of the attention (from our case and others) has been like squeezing a pimple. It has brought the pus to the top.

It was never my attention to directly talk about minority rights or the laws in Uganda — I would not presume to do so. It is none of my business, in every sense. What we were trying to do was to make fun of the nonsense surrounding attitudes to gays – the very bigotry and politicisation that took us down – without getting involved in a “right or wrong” argument. Our play was funny; it was entertainment. I hope that we changed the attitudes of some audience members.

I believe communities are the source of meaning. The law either follows or clashes with that meaning. Sometimes a law may be passed to protect a minority; maybe…

The problem with international activism is that it plays right into the hands of people who argue that homosexuality is a “foreign menace”. At least, people who care about these issues should spend a significant amount of time in the countries to understand why ordinary, sound people may be homophobic. Then they can judge and engage with them.

Activism is a label with revolutionary connotations. I am certainly no activist. At most, we wanted to get people talking.

Index: What role does freedom of expression have to play in discussions about homophobia, especially in countries where it is a crime to be gay?

David: Without freedom of expression, government propaganda and lazy “common sense” prevails, especially regarding taboos or controversies. In a country where religious, ethnic and gender identities are so important and politicised, it is essential that we can discuss politics in terms of our identity, without fear of arrest.

Index: How important are awards like the Index on Censorship one in advocating free speech as a human right?

David: In Uganda, there’s a fantastic organisation called “Freethought Kampala”. They’d benefit from exposure and affiliation. I’d love to see the Index organising an event with their founder James Onen and his friends.

This article was posted on March 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Uganda’s recently passed Anti-Pornography Act 2014 is believed to have led to targeting of women wearing mini-skirts, prompting the cabinet to review the law.

Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi told parliament recently that it is not the duty of the public but the police to implement the law: “The law is not about the length of one’s dress or skirt. As cabinet, we are going to look at the act again.”

The law, assented to by President Yoweri Museveni on 6 February this year, creates and defines the offence of pornography and its prohibition. It bans anyone from producing, trafficking, publishing, broadcasting, procuring, importing exporting or abetting any form of pornography.

Nowhere in the law is a ban on mini-skirts mentioned. The prime minister said that the term “indecent” as defined in the act to mean “non conformity with generally accepted standards” is too broad and varies from one person to another. “It’s very important that the law is clear and specific. I request the public not to take the law in their hands. It’s criminal, especially to women; they must be fully protected, and we shall protect them,” he said.

Initially, the bill proposed the prohibition of types of dress that exposed different body parts like breasts, thighs, genitalia and buttocks, but that clause was deleted before it was enacted into law. The law that was ultimately passed targets media organisations, Internet Service Providers (ISP’s), the entertainment and leisure industry and others putting what is deemed pornographic material into the public domain. Despite this, many women are afraid of the consequences of the law.

The apparent misunderstanding of the law by the public has generally been blamed on Ethics and Integrity Minister Simon Lokodo, who has suggested that it will ultimately help in the fight against indecent dressing by women. He has openly stated that “if a woman is dressed in attire that irritates the mind and excites other people of the opposite sex, you are dressed in wrong attire, so please you should hurry up and go home and change.” He maintains that women should “dress decently” because “men are so weak that if they saw an indecently dressed woman, they would just jump on her”. It should be noted that this minister is a former priest of the Catholic Church.

The act defines pornography as any cultural practice, radio or television programme, writing, publication, advertisement, broadcast, upload on the internet, display, entertainment, music, dance, picture, audio or video recording, show, exhibition or any combination of these that depicts a person engaged in explicit sexual activities or conduct; sexual parts of a person; erotic behaviour intended to cause sexual excitement or any indecent act or behaviour tending to corrupt morals.

The act also proposes setting up a Pornography Control Committee to, among other things, ensure that perpetrators of pornography are apprehended and prosecuted, and to collect and destroy all pornographic materials.

Ruth Ojiambo Othieno, the Executive Director of Isis-Women’s International Cross Cultural Exchange said she was disappointed that the law is targeting women and their bodies.

Miria Matembe, a woman’s activist and former ethics minister argues that the law is very vague and compares it to former President Idi Amin’s directive that women should not wear skirts and dresses more than three inches above the knee.

In a statement, police spokesperson Judith Nabakooba warned that if one suspects a person to be indecently dressed, they should report the matter to police but not take the law into their own hands. “Anyone found participating in mob justice of undressing people and are caught will be dealt with accordingly,” she said.

This article was posted on March 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

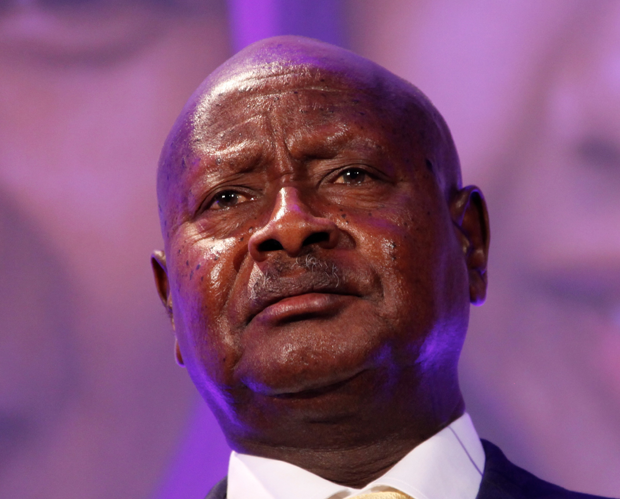

Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni (Photo: Wikipedia)

President Yoweri Museveni signed Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality bill into law on 24 February, and the fallout has already started. The World Bank has cancelled a $90 million loan to the country, European Union countries are threatening to withdraw aid, and the United States is reviewing its cooperation with Uganda. President Museveni has hit back, saying Uganda would raise its own money to fund its development projects. The US, which was the first voice its discontent, was told off: “Our relationship with the US was not based on homosexuality.” David Bahati, the MP who introduced the bill, said in an interview that the west is imposing social imperialism on Uganda, a thing they are not ready to accept.

“I will work with the Russians,” Museveni said.

So the president feels that even without the west, Uganda has development partners that it can still rely on. Considering he was not supportive of the so-called Bahati bill in its initial stages, Museveni’s last-minute change of heart is baffling.

The law stipulates that punishment for homosexuals will be a life jail sentence, while those who “attempt” to engage in homosexual acts face seven years in prison. The law also targets journalists and others seen to participate in “production, procuring, marketing, broadcasting, disseminating, publishing of pornographic materials for purposes of promoting homosexuality”. It even attempts to reach beyond the country’s borders, implong that Uganda will have to ask countries where gay Ugandans live to extradite them so that they can face the law.

Public opinion goes both ways. Many are happy that the president is standing firm against “the west” and the perceived scheme of promoting homosexuality in Uganda and Africa at large. Others claim that the president signed this law to achieve cheap popularity with the 2016 elections around the corner. It is also claimed that President Museveni is just playing his usual political games. When the anti-homosexuality bill was passed by parliament early this year, one of the president’s legal brains, Fox Odoi, publicly stated that if the president ever assents to this law, he would challenge it in court.

Odoi has now teamed up with Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda to take the case to the constitutional court. It is alleged that this was Museveni’s game plan: sign the law, annoy the west and appease the locals, and then have his henchmen challenge this law in court and make sure it remains there forever. In this case, the west will soften their stance towards Museveni, and the locals will be told to be patient and leave the legal process to take its course. In that case, he will have killed two birds with one stone, and would go for the 2016 elections with both the west and the locals in his pockets.

Civil society has also been critical, not because the anti-homosexuality law is unnecessary per se, but they have questioned whether homosexuality is the biggest problem Uganda faces today, and warrants such urgency. With high youth unemployment, squalid conditions in health facilities and theft of public funds in government institutions, they believe priorities should lie somewhere else other than “fixing” homosexuality.

“The timing for the assenting to this law by the president is meant to divert the country’s attention from the discussion on the deployment of Ugandan forces in South Sudan and our mandate there. This law is very diversionary, and it is unfortunate that Ugandans have swallowed the president’s bait,” said Godber Tumushabe, a renowned civil society activist.

Opposition leader Kizza Besigye has criticised the new law, saying that homosexuality was not “foreign” and that the issue was being used to divert attention from domestic problems. “Homosexuality is as Ugandan as any other behaviour, it has nothing to do with the foreigners,” said Besigye. He accused the government of having “ulterior motives” and using the issue to divert attention from other issues, including Uganda’s military backing of neighbouring South Sudan’s government against rebel forces.

Sweden’s Finance Minister Anders Borg, who visited the country a day after the signing of the law, said it “presents an economic risk for Uganda”. But Besigye accused them of double standards, saying that their cutting of aid over gay rights alone was “misguided”: ”They should have cut aid a long time ago because of more fundamental rights, our rights have been violated with impunity and they kept silent,” he said.

This article was posted on March 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org