Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

On Monday 16 September, the United States imposed financial sanctions and visa restrictions on Georgians who they believed to be involved with violent crackdowns on peaceful protests that had occurred in the country’s capital Tbilisi in the spring. The protests were sparked in resistance to the passing of a “foreign agents law”, which shares similarities with an existing law in Russia – raising concerns that the Georgian government is aligning more closely with the Kremlin.

These demonstrations were led by young adults. University students organised and turned out in their thousands, and the majority of protesters on the streets were members of Gen Z. It is commonplace for young people to be vocal about what they believe in, but despite the US supporting the struggle of the youth against their government in Georgia, when it comes to home soil, their commitment to free speech isn’t so steadfast. The US drew condemnation from UN human rights experts regarding the aggressive and harsh measures used by authorities against pro-Palestine protesters on US university campuses – many peaceful demonstrations were met with surveillance and arrests across the country. Further measures are being taken to prevent protests ahead of the 2024/25 academic year, and these have been met with disdain from the American Association of University Professors in a statement made last month.

The USA is far from alone when it comes to recent crackdowns on the right to protest. As Index has previously covered, there have been multiple arrests at both climate protests and pro-Palestine protests in the UK in recent years, and the Conservative government led by Rishi Sunak introduced the much criticised Policing, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, the Public Order Act 2023, and Serious Disruption Prevention Orders, all of which significantly inhibit people’s right to protest. This crushing of demonstrations even breached the realms of legality when Suella Braverman was ruled to have passed unlawful anti-protest legislation in 2023. In recent times, the sheer scale of punishment for non-violent protesters in the UK has been brought into the public eye with the sentencing in July of Roger Hallam of Just Stop Oil (JSO) to five years imprisonment, and four other JSO members to four years, for coordinating protests on the M25.

Lotte Leicht, a Danish human rights lawyer who holds the position of advocacy director at Climate Rights International – a monitoring and advocacy organisation that recently put out a statement outlining hypocrisy from western governments regarding climate protests – spoke to Index on this issue, and she believes that the UK is the worst offender.

“The crackdown, and particularly the use of law to sentence non-violent disruption by climate protesters in the UK has stood out as the most severe and most extraordinary measure [from any country]. And one thing that’s very disappointing from our point of view is not to see the new Labour government tackling these draconian laws from the previous government, and taking steps to revoke them,” Leicht said.

She added: “The prevention of UK activists from explaining their motivations for their actions in court, and judges actually preventing them from doing so… As a lawyer, I would say this prevents people from having a fair trial.”

This crackdown on protests has become prevalent in many democracies within ‘the Global North’ in recent years, and examples are not hard to come by. On 11 September, thousands of anti-war protesters in Melbourne, Australia gathered outside a weapons expo, protesting the government’s stance on arms, and the use of such weapons in Gaza. The protests quickly became the subject of great scrutiny when there were violent clashes between Melbourne police and demonstrators, with police allegedly using excessive “riot-type” force, resulting in multiple injuries.

In Germany, pro-Palestine protests have also repeatedly been met with harsh measures, such as bans. The country’s history of anti-Semitism has impacted its attitude towards protests and events that are critical of Israel, causing police to be more heavy handed than in other democracies.

Leicht, who is also the council chairwoman at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), a nonprofit dedicated to enforcing civil and human rights globally, told Index that this increasing anti-protest action from western democracies sets a very worrying precedent.

“This represents a massive deployment of double standards. Because these are the same governments that rightfully stand up for freedom of expression, association and assembly in different corners of the world when authoritarian governments are cracking down horrifically on dissent in their countries,” she said.

“These countries are usually there to say ‘Oh, that’s not good’, and we want them to do that! But by not practising what they preach and undermining these principles at home, they will lose that credibility. In a way, they will provide a green light to authoritarian governments to do the exact same for those that they don’t like. I mean, why not?”

Leicht does, however, believe that a continued struggle against these litigations will not be in vain.

“Protests in the past have also been disruptive, annoying and irritating for those in power — look at the Suffragettes. Now, is that something that we today would say ‘That’s just annoying and irritating’? Many felt so at the time. They were disruptive, they were irritating, they were strong, they were principled – and they were successful. And I think history will tell the same story about courageous climate protesters,” she said.

It is clear that countries positioning themselves as “champions of democracy” must truly allow freedom of expression within their own borders, especially when they set the tone globally. If they continue to infringe upon the rights of people to demonstrate their beliefs and advocate publicly for change, then the future will be silent.

Banned Books Week is here once again. And so too are more stories of books being censored across the world. This week, Pen America reported that the number of book bans in public schools has nearly tripled in 2023-24 from the previous school year.

While the week-long Banned Books Week event, supported by a coalition including Index on Censorship, looks largely towards bans in the USA, we’re taking a moment to reflect on global censorship of literature. We asked the Index team to share what they think is the most ridiculous instance of book censorship, from the outright silly to the baffling but dangerous. Some of these examples verge on amusing — the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s aversion to talking animals, for example — but the bans that have ended in attempted murders just go to show that the practice of book banning itself is completely nonsensical, and can lead to real harm.

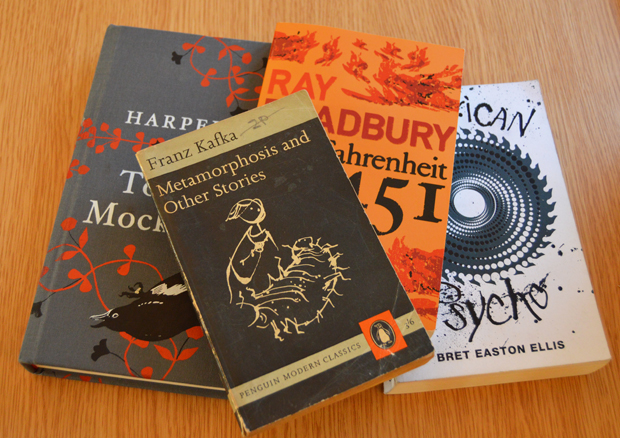

Banned Books (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

Too many talking animals

You don’t have to have children to imagine what a clichéd kids book might look like. Yes, you’ve guessed right – animated animals. Tigers, mice, dogs – they’re all common in children’s literature. But the Chinese authorities have an uncomfortable relationship with our furry friends.

In 2022 a Hong Kong court sent five people to prison for publishing a series of books called Sheep Village (and of course they banned the books too). To be fair these illustrated books, aimed at kids aged four to seven, didn’t code their political messages well: a flock of sheep (stand-in for Hong Kongers) peacefully resist a savage wolf pack (the guys in Beijing). So this might not be the most absurd example, though it did feel like an absurdly low moment.

However, what was clearly absurd on all levels was the 1931 ban of Alice in Wonderland by the governor of Hunan Province. The book’s crime? Talking animals. Apparently they shouldn’t have used human language and putting humans and animals on the same level was “disastrous”. What unites the CCP with the Republic of China that came before it? Unease around anthropomorphised animals it would seem.

Too many banned books

Ban This Book by Alan Gatz, a book about book bans, has been banned by the state flying the banner for banning books. This is not a tongue twister, riddle or code. It is the crystallisation of the absurdity of banning books.

In January 2024, the book was banned in Indian River County in Florida after opposition from parents linked to Moms for Liberty. According to the Tallahassee Democrat, the school board disliked how the book “referenced other books that had been removed from schools” and accused it of “teaching rebellion of school board authority”. When you are trying to reshape the world in line with your own blinkered view it is probably best not to draw attention to it by calling out reading as an act of rebellion. Just a thought.

The book tells the story of Amy Anne Ollinger’s fight to overturn a book ban in her fictional school library. The book’s conclusion leads Amy Anne “to try to beat the book banners at their own game. Because after all, once you ban one book, you can ban them all”.

This tells us something – the self-harming absurdity of book bans is apparent to kids like Amy Anne but not to the prudish administrators and thuggish groups wielding their mob veto like a weapon. Groups like Moms for Liberty and their fellow censors obscure the darkness of our shared history by removing any reference to it and by pretending it did not happen — not by addressing the root causes or working to ensure it does not happen again.

Too Belarusian

In Belarus, numerous books in the Belarusian language by the country’s best classical and modern writers have been banned, especially following the 2020 presidential election and pro-democracy protests. Unbelievably, Lukashenka’s regime — often called the last dictatorship in Europe and backed by Russia — views Belarusian historical, cultural and national identity as a threat.

Many books in Belarusian have been labelled extremist and even destroyed from the National Library’s collection since the protests started in August 2020. This includes Dogs of Europe by Alhierd Baharevich, works by 19th century writer Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievich and 20th century poet Larysa Hienijush, among others.

Too decadent and despairing

Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, possibly the greatest short story ever written, was banned by both the Nazis and the Soviets. Being a Jewish author, the Nazis burned Kafka’s books on their “sauberen” (cleansing) pyres. But in the Soviet Union, his books were banned as “decadent and despairing”. This was clearly a judgement made by officials without much knowledge of the history of the novel, where so many titles are filled with human despair. Without these, we would not get the contrasting light of decadent writers like Oscar Wilde and JK Huysmans.

Too mermaidy

One of my favourite books to read with my son is Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love. It’s a beautiful picture book where a young boy dreams of becoming a mermaid after seeing a school / pod (collective noun to be determined) of merfolk on the way to the Coney Island Mermaid Parade, then rummages around his nana’s home for a costume.

In various parts of the USA, Julian has been banned. In a school district in Iowa, it was flagged for removal under a law that “bans books that depict or describe sex acts”, which apparently also covers gender identity — there are definitely no sex acts in this book. In other districts, it’s been fully banned due to representing the LGBTQ+ community.

If book banners in the USA are really worried about kids becoming mermaids, then I’d like to know on what grounds. Because, quite frankly, I always wanted to be a mermaid, and if it turns out it was a viable option, I have some regrets. Personally, I’d be more concerned about Julian ripping down his nana’s curtains to make a tail, à la Julie Andrews making costumes for the Von Trapp children.

Too accurate

In Egypt, Metro, the country’s first graphic novel by Magdy El Shafee, was quickly banned after publication in 2008 for “offending public morals”. This was likely due to the novel’s depiction of a half-naked woman, inclusion of swear words and general portrayal of poverty and corruption in Egypt during the former president Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year rule. The author was charged under article 178 of the Egyptian penal code for infringing “upon public decency” and fined 5,000 LE. It was eventually republished in Arabic in 2012.

Too dystopian

Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian classic Brave New World explores an imagined future centred on productivity and enforced “happiness” at the expense of individual freedom. Set in 2540, society has been stripped of families, with babies manufactured synthetically with specific characteristics, then forced into a predetermined “caste” system. People are encouraged to prioritise short-term gratification through casual sex and taking a “happiness” drug called soma, making them blissfully unaware of their imprisonment within the system.

Since its publication nearly 100 years ago, the novel has caused controversy globally. It was initially banned in Ireland and Australia in 1932 for eschewing traditional familial and religious values, then later banned in India in 1967 for its sexual content, with Huxley even being referred to as a “pornographer” for depicting a society that encourages recreational sex. It is still banned in many classrooms and libraries across America for a range of wild reasons, from use of offensive language and sexual explicitness to racism and “conflict with a religious viewpoint”.

But Huxley’s imagined future is one of horror. He uses themes of enforced, unfettered pleasure and a twisted genetic-based class system to express how humans’ complex problems and moral quandaries cannot be solved by scientific advancement alone. The main point of dystopian fiction is to tell a cautionary tale of the levels of exploitation that society could sink to, in order to save the world at large. While it was undoubtedly shocking and crass for its time, the fact that Huxley’s novel still ruffles feathers reveals a complete misunderstanding of allegory.

Too many lesbians

I first read Radclyffe Hall’s legendary lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, with bated breath as a young, closeted queer person. Her portrayal of young woman ‘Stephen’ Gordon and her romance with Mary Llewellyn was wildly liberating and satisfying to read. Of course, as a product of its time it is in many ways outdated and of course laced with problematic values, for example biphobia and misogyny. But it was hugely important in terms of normalising queer relationships over a century ago.

Shortly after publication, the book went to trial in Britain on the grounds of “obscenity” and was subsequently banned — but this is no Lady Chatterley’s Lover. There are no real ‘hot under the collar moments’. The only ‘obscenity’ was the portrayal of two women in a romantic relationship, even though (unlike male homosexuality), lesbianism wasn’t actually illegal in 1928.

Too friendly

The award-winning writer and painter Leo Lionni’s first children’s book Little Blue and Little Yellow (1959) is a short story for young children about two best friends who, one day, can’t find each other. When they meet again, they give each other such a big hug that they turn green.

Despite its important message about the power of love and friendship, the mayor of Venice decided to ban it from all preschools in the province for “undermining traditional family values”. It was one of more than 50 children’s books to have been banned just days after he took up the post after his election in 2015.

Too uncensored

As ironies go, the banning of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 may be the strangest. The novel describes a dystopian future in which books are banned and “firemen” burn any that are found – its title comes from the ignition temperature of paper.

In 1967, a new edition of the book aimed at high schools, known as the Bal-Hi edition, was substantially altered to remove swear words and references to drug use, nudity and drunkenness. Somehow, the censored text came to be used for the mass-market edition in 1973 and “for the next six years no uncensored paperback copies were in print, and no one seemed to notice”, wrote Jonathan R. Eller in the introduction to the 60th anniversary edition of the book.

Readers eventually realised and alerted Bradbury. He demanded that the publisher retract the censored version, writing that he would “not tolerate the practice of manuscript ‘mutilation’”.

Too unflattering

It’s not altogether surprising that UK authorities attempted to prevent the autobiography of former MI5 officer Peter Wright, Spycatcher (co-written by Paul Greengrass), from hitting the shelves. The book did not present British intelligence agencies in a flattering light, and the government’s claims that they were suppressing its publication in the interests of security — rather than to save face — were eventually dismissed by the courts.

However, the ridiculous part about this book banning was that it only applied to England and Wales and the book was freely accessible elsewhere — including Scotland. This led to an absurd situation where newspapers around the world were reporting on the book’s contents while the press in England was subject to a gagging order, despite the information having already been revealed and books being easily shipped into the country. The ban was eventually lifted after it was acknowledged that the book wasn’t exposing any secrets due to its overseas publication.

Too blasphemous

The most absurd book banning is also, arguably, the most serious in recent history. The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie was published in 1988 to deserved critical acclaim. It is a playful and complex novel that examines, among other things, the origins of Islam. The death sentence imposed on the author by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini was fuelled by, and in turn itself fuelled an ideology that believes that a novel can be blasphemous and its author should be killed. It would be laughable if the consequences weren’t so deadly.

The Summer 2024 issue of Index looks at how cinema is used as a tool to help shape the global political narrative by investigating who controls what we see on the screen and why they want us to see it. We highlight examples from around the world of states censoring films that show them in a bad light and pushing narratives that help them to scrub up their reputation, as well as lending a voice to those who use cinema as a form of dissent. This issue provides a global perspective, with stories ranging from India to Nigeria to the US. Altogether, it provides us with an insight into the starring role that cinema plays in the world politics, both as a tool for oppressive regimes looking to stifle free expression and the brave dissidents fighting back.

Lights, camera, (red)-action, by Sally Gimson: Index is going to the movies and exploring who determines what we see on screen

The Index, by Mark Stimpson: A glimpse at the world of free expression, including an election in Mozambique, an Iranian feminist podcaster and the 1960s TV show The Prisoner

Banned: school librarians shushed over LGBT+ books, by Katie Dancey-Downs: An unlikely new battleground emerges in the fight for free speech

We’re not banned, but…, by Simon James Green: Authors are being caught up in the anti-LGBT+ backlash

The red pill problem, by Anmol Irfan: A group of muslim influencers are creating a misogynistic subculture online

Postcards from Putin’s prison, by Alexandra Domenech: The Russian teenager running an anti-war campaign from behind bars

The science of persecution, by Zofeen T Ebrahim: Even in death, a Pakistani scientist continues to be vilified for his faith

Cinema against the state, by Zahra Hankir: Artists in Lebanon are finding creative ways to resist oppression

First they came for the Greens, by Alessio Perrone, Darren Loucaides and Sam Edwards: Climate change isn’t the only threat facing environmentalists in Germany

Undercover freedom fund, by Gabija Steponenaite: Belarusian dissidents have a new weapon: cryptocurrency

A phantom act, by Danson Kahyana: Uganda’s anti-pornography law is restricting women’s freedom - and their mini skirts

Don’t say ‘gay’, by Ugonna-Ora Owoh: Queer Ghanaians are coming under fire from new anti-LGBT+ laws

Money talks in Hollywood, by Karen Krizanovich: Out with the old and in with the new? Not on Hollywood’s watch

Strings attached, by JP O’Malley: Saudi Arabia’s booming film industry is the latest weapon in their soft power armoury

Filmmakers pull it out of the bag, by Shohini Chaudhuri: Iranian films are finding increasingly innovative ways to get around Islamic taboos

Edited out of existence, by Tilewa Kazeem: There’s no room for queer stories in Nollywood

Making movies to rule the world, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Author Erich Schwartzel describes how China’s imperfections are left on the cutting room floor

When the original is better than the remake, by Salil Tripathi: Can Bollywood escape from the Hindu nationalist narrative?

Selected screenings, by Maria Sorensen: The Russian filmmaker who is wanted by the Kremlin

A chronicle of censorship, by Martin Bright: A documentary on the Babyn Yar massacre faces an unlikely obstacle

Erdogan’s crucible by Kaya Genc: Election results bring renewed hope for Turkey’s imprisoned filmmakers

Race, royalty and religion - Malaysian cinema’s red lines, by Deborah Augustin: A behind the scenes look at a banned film in Malaysia

Join the exiled press club, by Can Dundar: A personalised insight into the challenges faced by journalists in exile

Freedoms lost in translation, by Banoo Zan: Supporting immigrant writers - one open mic poetry night at a time

Me Too’s two sides, by John Scott Lewinski: A lot has changed since the start of the #MeToo movement

We must keep holding the line, by Jemimah Steinfeld: When free speech is co-opted by extremists, tyrants are the only winners

It’s not normal, by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe: Toomaj Salehi’s life is at the mercy of the Iranian state, but they can’t kill his lyrics

No offence intended, by Kaya Genc: Warning: this short story may contain extremely inoffensive content

The unstilled voice of Gazan theatre, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: For some Palestinian actors, their characters’ lives have become a horrifying reality

Silent order, by Fujeena Abdul Kader, Upendar Gundala: The power of the church is being used to censor tales of India’s convents

Freedom of expression is the canary in the coalmine, by Mark Stimpson and Ruth Anderson: Our former CEO reflects on her four years spent at Index

The Spring 2024 issue of Index looks at how authoritarian states are bypassing borders in order to clamp down on dissidents who have fled their home state. In this issue we investigate the forms that transnational repression can take, as well as highlighting examples of those who have been harassed, threatened or silenced by the long arm of the state.

The writers in this issue offer a range of perspectives from countries all over the world, with stories from Turkey to Eritrea to India providing a global view of how states operate when it comes to suppressing dissidents abroad. These experiences serve as a warning that borders no longer come with a guarantee of safety for those targeted by oppressive regimes.

Border control, by Jemimah Steinfeld: There's no safe place for the world's dissidents. World leaders need to act.

The Index, by Mark Frary: A glimpse at the world of free expression, featuring Indian elections, Predator spyware and a Bahraini hunger strike.

Just passing through, by Eduardo Halfon: A guided tour through Guatemala's crime traps.

Exporting the American playbook, by Amy Fallon: The culture wars are finding new ground in Canada, where the freedom to read is the latest battle.

The couple and the king, by Clemence Manyukwe: Tanele Maseko saw her activist husband killed in front of her eyes, but it has not stopped her fight for democracy.

Obrador's parting gift, by Chris Havler-Barrett: Journalists are free to report in Mexico, as long as it's what the president wants to hear.

Silencing the faithful, by Simone Dias Marques: Brazil's religious minorities are under attack.

The anti-abortion roadshow, by Rebecca L Root: The USA's most controversial new export could be a campaign against reproductive rights.

The woman taking on the trolls, by Daisy Ruddock: Tackling disinformation has left Marianna Spring a victim of trolling, even by Elon Musk.

Broken news, by Mehran Firdous: The founder of The Kashmir Walla reels from his time in prison and the banning of his news outlet.

Who can we trust?, by Kimberley Brown: Organised crime and corruption have turned once peaceful Ecuador into a reporter's nightmare.

The cost of being green, by Thien Viet: Vietnam's environmental activists are mysteriously all being locked up on tax charges.

Who is the real enemy?, by Raphael Rashid: Where North Korea is concerned, poetry can go too far - according to South Korea.

The law, when it suits him, by JP O'Malley: Donald Trump could be making prison cells great again.

Nowhere is safe, by Alexander Dukalskis: Introducing the new and improved ways that autocracies silence their overseas critics.

Welcome to the dictator's playground, by Kaya Genç: When it comes to safeguarding immigrant dissidents, Turkey has a bad reputation.

The overseas repressors who are evading the spotlight, by Emily Couch: It's not all Russia, China and Saudi Arabia. Central Asian governments are reaching across borders too.

Everything everywhere all at once, by Daisy Ruddock: It's both quantity and quality when it comes to how states attack dissent abroad.

A fatal game of international hide and seek, by Danson Kahyana: After leaving Eritrea, one writer lives in constants fear of being kidnapped or killed.

Our principles are not for sale, by Jirapreeya Saeboo: The Thai student publisher who told China to keep their cash bribe.

Refused a passport, by Sally Gimson: A lesson from Belarus in how to obstruct your critics.

Be nice, or you're not coming in, by Salil Tripathi: Is the murder of a Sikh activist in Canada the latest in India's cross-border control.

An agency for those denied agency, by Amy Fallon: The Sikh Press Association's members are no strangers to receiving death threats.

Always looking behind, by Zhou Fengsuo and Nathan Law: If you're a Tiananmen protest leader or the face of Hong Kong's democracy movement, China is always watching.

Putting Interpol on notice, by Tommy Greene: For dissidents who find themselves on Red Notice, it's all about location, location, location

Living in Russia's shadow, by Irina Babloyan, Andrei Soldatov and Kirill Martynov: Three Russian journalists in exile outline why paranoia around their safety is justified.

Solidarity, Assange-style, by Martin Bright: Our editor-at-large on his own experience working with Assange.

Challenging words, by Emma Briant: An academic on what to do around the weaponisation of words.

Good, bad and everything that's in between, by Ruth Anderson: New threats to free speech call for new approaches.

Ukraine's disappearing ink, by Victoria Amelina and Stephen Komarnyckyj: One of several Ukrainian writers killed in Russia's war, Amelina's words live on.

One-way ticket to freedom?, by Ghanem Al Masarir and Jemimah Steinfeld: A dissident has the last laugh on Saudi, when we publish his skit.

The show must go on, by Katie Dancey-Downs, Yahya Marei and Bahaa Eldin Ibdah: In the midst of war Palestine's Freedom Theatre still deliver cultural resistance, some of which is published here.

Fight for life - and language, by William Yang: Uyghur linguists are doing everything they can to keep their culture alive.

Freedom is very fragile, by Mark Frary and Oleksandra Matviichuk: The winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize on looking beyond the Nuremberg Trials lens.