Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Mamadali Makhmudov

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” size=”lg” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Pohyon Temple in the Myohyang mountains, once a national center for Korean Buddhism. Credit: Uri Tours / Flickr

After the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, an independent organisation created by the US Congress to evaluate religious freedom conditions around the world, released its 2015 report, it became clear that an insufficient amount of progress had been made since Index on Censorship last reported on the issue.

Here’s a roundup of some the most appalling religious freedom violations from across the globe.

Burma

Bigotry and intolerance continue to scorch the lives of religious and ethnic minorities in Burma, particularly Rohingya Muslims. The Burmese government demonstrated little effort toward intervening or properly investigating claims of abuse, including those carried out by religious figures in the Buddhist community. As internet availability spread throughout the country, social media played a role in promoting a platform of hate and proposed violence against minority populations. Rohingya Muslims in the country face a unique level of discrimination and persecution. The government denies them citizenship and the right to identify as Rohingya. Additionally, four discriminatory race and religion bills could further the prejudices affecting religious minorities.

North Korea

North Korea is a nation where genuine freedom of religion or belief is non-existent; it remains one of the most oppressive regimes and worst violators of human rights. Punishment comes to those who pose difficult questions while the government maintains its control through a constant threat of imprisonment, torture and even death for those who break the law regarding religion. Estimates suggest up to 200,000 North Koreans are currently suffering in labor camps, tens of thousands of whom are there for practicing heir faith. In February 2014, the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea released its report documenting the systematic, severe violations of human rights in the country. It found “an almost complete denial of the right to freedom of thought, conscience”.

Saudi Arabia

Officially an Islamic state with eight to ten million expatriate workers of different faiths, Saudi Arabia continues to restrict most forms of public religious expression inconsistent with its interpretation of Sunni Islam. The government continues to use criminal charges of blasphemy to suppress any dialogue between dissenting viewpoints, with a new law helping drive home the goal of silence. The Penal Law for Crimes of Terrorism and its Financing criminalises virtually all forms of peaceful dissent and free expression, including criticising the government’s view of Islam. Lastly, authorities continue to discriminate grossly against dissident clerics and members of the Shia community.

Sudan

The Sudanese government continues to engage in massive violations of freedom of religion, due to president Omar al-Bashir’s policies of Islamisation and restrictive interpretation of sharia law. Despite 97% of the population being Muslim, there is a wide range of other religions practiced. The country’s turmoil from religious persecution rests on the 1991 Criminal Code, the 1991 Personal Status Law of Muslims, and state-level “public order” laws, which have restricted freedom for all Sudanese. The laws – which contradict the country’s constitutional and international commitments to human rights and freedom of religion – allow death sentences for apostasy, stoning for adultery, cross-amputations for theft, prison sentences for blasphemy and floggings for undefined “offences of honor, reputation and public morality”. Since 2011, more than 170 people have been arrested and charged with apostasy.

Article continues below

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Join the Index mailing list and get an exclusive gift” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s summer magazine 2016

We’ll send you our weekly emails and periodic updates on our events. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.

You’ll also get access to an exclusive collection of articles from our landmark 250th issue of Index on Censorship magazine exploring journalists under fire and under pressure. Your downloadable PDF will include reports from Lindsey Hilsum, Laura Silvia Battaglia and Hazza Al-Adnan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, the government imprisons individuals for not conforming to officially prescribed practices or whom it claims are extremist, including as many as 12,000 Muslims. A highly restrictive religion law is imposed, the 1998 Law on Freedom of Consciences and Religious Organisations, which severely limits the rights of all religious groups and facilitates Uzbek government control over religious activity. Many who don’t fit into the framework of officially approved practices are regularly repressed. Additionally, the government has continued a campaign against independent Muslims, targeting those linked to the May 2005 protests in Andijan; 231 are still imprisoned in connection to the events, and ten have died. All the while, Uzbekistan has pressured countries to return Uzbek refugees who fled during the Andijan tragedy.

Turkmenistan

In an environment of nearly inescapable government information control, severe religion freedom breaches persist in Turkmenistan. Continuing police raids and harassment of registered and unregistered religious groups matched with laws and policies that violate international human rights norms has the nation as one of the year’s biggest offenders. With an estimated total population of 5.1 million, the US government projects that the country is 85% Sunni Muslim, 9% Russian Orthodox, and a 2% total that includes Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, and evangelical Christians. Despite Turkmenistan’s constitutionally guaranteed religious freedom and separation of religion from the state, the 2003 religion law negates these provisions while setting intrusive registration criteria for individuals. It also requires that the government is informed of all foreign financial support, forbids worship in private homes and places discriminatory restrictions on religious education.

China

While the Chinese constitution guarantees freedom of religion, this idea really only applies to “normal religions”, better known as the five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” associated with Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and Protestantism. Even still, the government monitors religious activities unfairly, and there has been an increased religious persecution of Uighur Muslims in the name of fighting terrorism. All around repression in China worsened in 2014, including the governmental push for controlling Tibet, Xinjiang, and even Hong Kong, as well as controls on the internet, social media, human rights defenders, activists and journalists.

Eritrea

Ongoing religious freedom abuses have continued in Eritrea, including torture or ill-treatment of religious prisoners, random arrests without charges and banning’s on public religious activities. The situation is especially serious for Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians and Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the government suppresses Muslim religious activities and those opposed to the government-appointed head of the community. In 2002, the government increased its control over religion by imposing a registration requirement on all religious groups other than the Coptic Orthodox Church of Eritrea, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church of Eritrea. The requirements mandated that the non-preferred religious communities provide detailed information about their finances, membership, activities, and benefit to the country. Additionally, released religious prisoners have reported to USCIRF that they were confined in crowded conditions, and subjected to extreme temperature fluctuations. The government continued to arrest and detain followers of unregistered religious communities. Recent estimates suggest 1,200 to 3,000 people are imprisoned on religious grounds in Eritrea, the majority of whom are Evangelical or Pentecostal Christians.

Iran

Poor religious freedom in Iran continued to worsen in 2014, particularly for minority groups like Bahá’ís, Christian converts, and Sunni Muslims. The government is still engaging in systematic violations, including prolonged detention, torture, and executions based on the religion of the accused. Despite Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians being recognised as protected minorities, the government has consistently discriminated against its citizens on the basis of religion. Killings, arrests, and physical abuse of detainees have increased in recent years, including for religious minorities and Muslims who are perceived as threatening the government’s legitimacy.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493906845781-a7b9ac80-f77d-2″ taxonomies=”1742″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

(Image: Oscar Mota/YouTube)

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

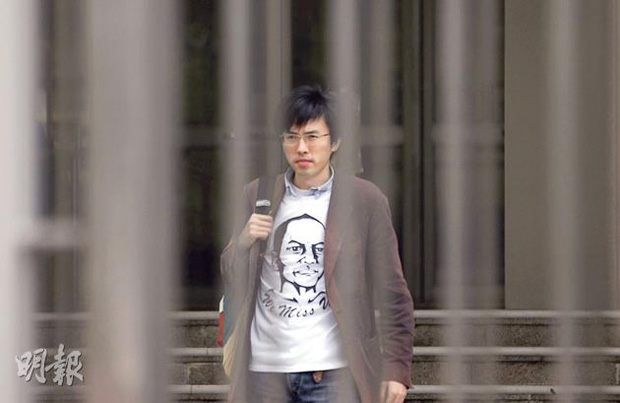

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Umida Akhmedova took part in a small protest in Tashkent, in solidarity with the Euromaidan movement.

On 27 January, internationally renowned photographer Umida Akhmedova, her son Timur Karpov and seven other people took to the streets of Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Armed with Ukrainian flags, cameras and a petition, they staged a peaceful protest in solidarity with the Euromaidan movement.

Knowing they might attract unwanted attention, the group, which included one journalist reporting, posed for a few photos outside the Ukrainian embassy, handed over the petition, and quickly wrapped up the demonstration. However, their worries soon proved valid. Three days later, the protesters were hauled in one by one by police for a “short talk”. They would be held incommunicado for one day, first in a central Tashkent police station and later at a more remote location.

Karpov, a photographer based in Russia, told Index about unprofessional and aggressive officers, who called the protesters “dissidents” who were “ruining the constitution”. Passports and phones were taken away, but Karpov managed to keep one concealed to alert the outside world to their detention. It was eventually discovered and confiscated. When he got it back, it had been completely wiped. Without access to lawyers, the protesters were questioned by the SNB — the KGB’s successor — before being put through a quickie court session and ordered to pay fines of some £1,200. Three of them have been sentenced to 15 days in prison. Justice, as understood by Uzbekistan’s notoriously repressive regime.

This is not the first time Akhmedova has run into trouble with the regime of former Communist Party official Islam Karimov. In 2009, the photographer and documentary film maker, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was charged with “damaging the country’s image” over a series of photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan. Similar charges were later levelled at her over a film about challenges facing Uzbek women, and in 2010, over a book about Uzbek traditions. It’s worth noting that she never intended to make a political statement with her work — the authorities’ reaction is what has politicised it. The cases have made Akhmedova a credible voice of opposition, and while her high profile provides some protection, it also means her every move is noted — as the latest case shows.

“We live in a strict, archaic society, where all unregulated acts, especially those that can cause some kind of a response in the society, are nipped in the bud,” she told Index. “In the case of our Maidan project, the authorities did not have to be clairvoyants to see the similarities between the situation in Ukraine and the one in Uzbekistan. The government has started scaring children and adults with the word Maidan and did not like it when we showed support for Maidan.”

“As for our previous case,” she adds “we were charged with slander and insult of Uzbek nation, because the government wanted to teach us a lesson that without the approval from above, we were not allowed to film anything or publish books, or generally, do anything artistic without a superior permission.”

While Akhmedova’s latest arrest hit headlines across Central Asia, the story made little impact in the west. This is not surprising. Earlier this year the soap opera-like falling out between first daughter Gulnara Karimova — businesswoman, sometimes pop star, and until recently tipped to follow in her father’s presidential footsteps — and, seemingly, the rest of the family was covered by media outside the country. But on the whole, Uzbekistan rarely commands international attention. Like many other countries in the region, it is able to carry out its repressive rule away from the global spotlight.

President Karimov, by taking a number of liberties with the country’s constitution and term limits, has been in power since it gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Reports of torture and other power abuses are widespread, the darkest days of the regime coming with the Andijan massacre, where security forces killed hundreds of people in the aftermath of a peaceful protest. The country is also one of the most corrupt in the world and despite its gas resources — part of the reason for many western sanctions quietly being dropped — suffers “recurring energy crises“. But Karimov has been careful to remove nearly all institutions that might use this information to challenge his power. Uzbekistan has no official opposition parties and no press freedom to speak of. Opposition news sites that operate outside of the country are blocked. Karpov puts it simply: “There is no freedom of expression in Uzbekistan. Absolutely none.”

One aspect of the widespread press censorship, is that developments in Ukraine have been met with near media blackout in Uzbekistan — the same way authorities dealt with the Arab spring and other incidents of popular unrest outside the country’s borders.

“From my point of view, they’re afraid. Extremely afraid of any sort of freedom,” says Karpov. ” That’s why they made the case with us. To frighten us. To show to other people that if you do this, you will be sentenced.”

Mother and son have accepted their punishment — partly because refusal to do so would lead to further blacklisting, and partly because they weren’t alerted to their appeal until after it had taken place. Unsurprisingly, the sentences were not overturned.

Despite this latest setback, and the possibility of being handed down a travel ban, Akhmedova remains undeterred. “Nothing has changed for me. I will carry on ‘slandering’ as I have done,” she says. “The state cannot help or stop me.”

This article was originally posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org