Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Venezuelans will cast their vote for the country’s next leader next Sunday, choosing between a president who is dominating the public space but has not answered a reporter’s question since last year, and an opposition candidate who is all but barred from TV and radio and is relying on social media to spread his message.

The election on 28 July sees authoritarian president Nicolas Maduro squaring off against opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez, who is leading in the polls despite receiving almost no exposure on traditional media.

Instead, Gonzalez and his main backer, opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, have relied on Instagram and TikTok videos, as well as WhatsApp viral messages, to galvanise the democratic opposition ahead of the vote.

This week, Caracas is plastered with election banners showing a smiling Maduro projecting confidence for Venezuela’s future, but journalists hoping to travel to Venezuela to interview him are set for a letdown, as the authoritarian leader has not conceded an interview since December and several international media have seen their visa requests denied in recent days.

The country’s Ministry of Communication closed applications to cover the election on 19 April. Everyone entering the country to report without proper accreditation, or outside the dates granted by the ministry, is at risk of being deported.

Maduro’s weekly agenda is top secret for security reasons, which means most reporters who are already in Venezuela are not informed when the candidate is holding a rally and are kept away from the campaign.

Earlier this month, Reporters Without Borders called on Venezuelan authorities to allow local and international journalists to cover the election, especially since the government withdrew an invitation for EU electoral observers in June.

Yet, in the first week of the campaign Maduro has racked up over 1,400 minutes of airtime on Venezuela’s public television station, while none of the other candidates were covered for more than 15 minutes, the Spanish news agency EFE reported.

None of this is new for Venezuela, a country where almost 300 radio stations were shut down by the National Telecommunications Commission (CONATEL) in the last two decades on charges of operating clandestinely, according to the local NGO Espacio Público — it has been reported today that their site has been geoblocked.

Radio stations are particularly censored, critics claim, because in a country with chronic electricity and internet problems, they often represent the only information channel available to the most vulnerable sectors of the country, where government support is stronger.

“When Gonzalez announced his candidature a couple months ago, all international media started interviewing him, but did we? We can’t do that,” a radio journalist in Caracas told Index this week, asking for their identity to remain anonymous for fears of being fired if they denounced censorship in the workplace.

Government censors from CONATEL constantly monitor the airwaves searching for dissident content and send warnings to the radio station’s management if any programme is deemed too leaning against the government, the reporter told Index.

The current tension in the newsroom is reminiscent of another recent episode of political tension, when opposition leader Juan Guaidó mounted a constitutional challenge against Maduro by swearing himself in as interim president.

“Our programme was taken off the air back then when two guests, political analysts, both referred to the government as ‘the dictatorship of Nicolas Maduro,’” the reporter told Index.

“I remember it was a Friday, I left the office and went home. The following Sunday I was doing calls to plan the week ahead when our executive producer told me the programme was being cancelled. Management decided to take the show off the air because CONATEL had called in, complaining that nobody corrected the guests. I spent the following four months doing nothing before a new programme came around,” they said.

From that moment, all radio studios in this reporter’s organisation have installed an instruction document next to the main console, advising the programme’s director to correct any guest suggesting Maduro’s government is not legitimate.

In recent years, radio stations have diversified their coverage by allowing reporters to write more freely when posting online, where the government’s censors have a harder time controlling who’s behind problematic content.

This double standard, however, only makes the self-censorship on radio programmes even more evident.

“Online we made a profile of each candidate running in the election, we also did other opposition leaders… But on air? That’s not going to happen,” the reporter said.

Luz Mely Reyes, who co-founded online media Efecto Cocuyo in 2015 after decades working in print, told Index that none of this is new, saying: “Censorship in Venezuela is systemic, it runs deeper than the yoke on radio and TV stations.”

Despite escaping the jurisdiction of CONATEL’s censors, Venezuelans need a VPN to access Efecto Cocuyo’s URL, which is geoblocked by the government. Venezuelan companies are also wary of purchasing adverts on the website, fearful they might incur trouble with the government.

“Sometimes, security becomes a factor too. You end up asking yourself: is it worth it to send one of my reporters to cover this, or that? It’s not like they give you an order, they want to force you to self-censor your coverage,” Reyes told Index.

Still, both traditional and new media are finding new strategies to keep the lights on for free information in Venezuela.

“Silence in radio speaks volumes, sometimes, I just leave blanks in the radio report,” the anonymous radio reporter told Index. “I can’t say that this is an authoritarian regime, but I can give the latest malnutrition figures an organisation has shared, and in the end the audience can make up their mind.”

After a moment of pause, they sighed: “Being a journalist in Venezuela is frustrating: there are no opportunities, the pay is shit, and journalism itself is at risk… but what fuels me is the hope that, one day, things change.”

Sonya Groysman is a Russian journalist and podcaster. Despite being labelled as a ‘foreign agent’ by Russian authorities she has continued to report on human rights issues and censorship in Russia.

Sonya Groysman is a Russian journalist and podcaster. Despite being labelled as a ‘foreign agent’ by Russian authorities she has continued to report on human rights issues and censorship in Russia. Bilal Hussain is a journalist based in Srinagar in Kashmir. He focuses his reporting on freedom of expression issues.

Bilal Hussain is a journalist based in Srinagar in Kashmir. He focuses his reporting on freedom of expression issues. Huang Xueqin is an activist and journalist who has worked with several domestic Chinese media outlets. She has reported extensively on the MeToo movement in China.

Huang Xueqin is an activist and journalist who has worked with several domestic Chinese media outlets. She has reported extensively on the MeToo movement in China. Venezuela Inteligente (VE inteligente) is a non-profit organisation which works to empower civil society and media organisations in Venezuela. They fight for freedom of expression and civic engagement online and offline.

Venezuela Inteligente (VE inteligente) is a non-profit organisation which works to empower civil society and media organisations in Venezuela. They fight for freedom of expression and civic engagement online and offline. Malcolm Bidali is a labour rights defender and blogger from Kenya. In 2021, Bidali was arrested after writing about the realities of being an immigrant worker in Qatar.

Malcolm Bidali is a labour rights defender and blogger from Kenya. In 2021, Bidali was arrested after writing about the realities of being an immigrant worker in Qatar. OVD-Info is an independent human rights media project documenting political persecution in Russia. With the help of a hotline, they collect information about detentions at public rallies and other cases of political pressure, publish news and coordinate legal assistance to detainees.

OVD-Info is an independent human rights media project documenting political persecution in Russia. With the help of a hotline, they collect information about detentions at public rallies and other cases of political pressure, publish news and coordinate legal assistance to detainees.[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ak Welsapar, Julian Baggini, Alison Flood, Jean-Paul Marthoz and Victoria Pavlova”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

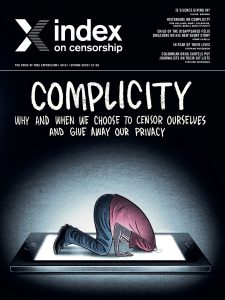

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Willingly watched by Noelle Mateer: Chinese people are installing their own video cameras as they believe losing privacy is a price they are willing to pay for enhanced safety

The big deal by Jean-Paul Marthoz: French journalists past and present have felt pressure to conform to the view of the tribe in their reporting

Don’t let them call the tune by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: A professor debates the moral questions about speaking at events sponsored by an organisation with links to the Chinese government

Chipping away at our privacy by Nathalie Rothschild: Swedes are having microchips inserted under their skin. What does that mean for their privacy?

There’s nothing wrong with being scared by Kirsten Han: As a journalist from Singapore grows up, her views on those who have self-censored change

How to ruin a good dinner party by Jemimah Steinfeld: We’re told not to discuss sex, politics and religion at the dinner table, but what happens to our free speech when we give in to that rule?

Sshh… No speaking out by Alison Flood: Historians Tom Holland, Mary Fulbrook, Serhii Plokhy and Daniel Beer discuss the people from the past who were guilty of complicity

Making foes out of friends by Steven Borowiec: North Korea’s grave human rights record is off the negotiation table in talks with South Korea. Why?

Nothing in life is free by Mark Frary: An investigation into how much information and privacy we are giving away on our phones

Not my turf by Jemimah Steinfeld: Helen Lewis argues that vitriol around the trans debate means only extreme voices are being heard

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: You’ve just signed away your freedom to dream in private

Driven towards the exit by Victoria Pavlova: As Bulgarian media is bought up by those with ties to the government, journalists are being forced out of the industry

Shadowing the golden age of Soviet censorship by Ak Welsapar: The Turkmen author discusses those who got in bed with the old regime, and what’s happening now

Silent majority by Stefano Pozzebon: A culture of fear has taken over Venezuela, where people are facing prison for being critical

Academically challenged by Kaya Genç: A Turkish academic who worried about publicly criticising the government hit a tipping point once her name was faked on a petition

Unhealthy market by Charlotte Middlehurst: As coronavirus affects China’s economy, will a weaker market mean international companies have more power to stand up for freedom of expression?

When silence is not enough by Julian Baggini: The philosopher ponders the dilemma of when you have to speak out and when it is OK not to[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Generations apart by Kaya Genç and Karoline Kan: We sat down with Turkish and Chinese families to hear whether things really are that different between the generations when it comes to free speech

Crossing the line by Stephen Woodman: Cartels trading in cocaine are taking violent action to stop journalists reporting on them

A slap in the face by Alessio Perrone: Meet the Italian journalist who has had to fight over 126 lawsuits all aimed at silencing her

Con (census) by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Turns out national censuses are controversial, especially in the countries where information is most tightly controlled

The documentary Bolsonaro doesn’t want made by Rachael Jolley: Brazil’s president has pulled the plug on funding for the TV series Transversais. Why? We speak to the director and publish extracts from its pitch

Queer erasure by Andy Lee Roth and April Anderson: Internet browsing can be biased against LGBTQ people, new exclusive research shows[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Up in smoke by Félix Bruzzone: A semi-autobiographical story from the son of two of Argentina’s disappeared

Between the gavel and the anvil by Najwa Bin Shatwan: A new short story about a Libyan author who starts changing her story to please neighbours

We could all disappear by Neamat Imam: The Bangladesh novelist on why his next book is about a famous writer who disappeared in the 1970s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Demand points of view by Orna Herr: A new Index initiative has allowed people to debate about all of the issues we’re otherwise avoiding[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Ticking the boxes by Jemimah Steinfeld: Voter turnout has never felt more important and has led to many new organisations setting out to encourage this. But they face many obstacles[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]