5 Jul 2019 | News and features, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“What is said and what is written is unbelievably important,” said Trevor Phillips, chairman of the board of Index on Censorship, at the close of the recent launch party for the Summer 2019 edition of Index Magazine.

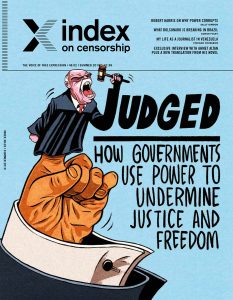

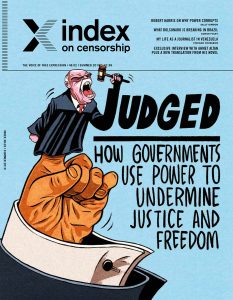

The summer 2019 edition, Judged: How Governments Use Power to Undermine Justice and Freedom, looks at attempts to undermine freedom of expression through attacks on the judiciary. The magazine covers issues ranging from new laws in Venezuela intended to limit freedom of the press to instances of self-censorship due to government control of content-sharing platforms in China to new technology created by journalists to check back against threats from politicians regarding the coverage of recent elections in South Africa.

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index magazine, explained that the idea behind the theme came from conversations she had with journalists in Italy covering areas with limited press freedom and hostile environments for journalists. She said, “one of the things that [the journalists] said kept them going was that there were still lawyers who were willing to stand up with them and defend them when they were attacked, when they had libel suits against them, when all the things that happen to them mean that they end up having to stand before a judge.”

This inspired Jolley to curate the latest edition of the magazine around legal issues, to address the legal fight for free speech behind the work of journalists to liberate the media under repressive regimes.

The keynote speaker of the evening was German writer Regula Venske, whose article What Does Weimar Mean to us 100 Years On? was published in the issue. Venske spoke about the history and ultimate downfall of the Weimar Republic, which is now known for fraught democracy and the promotion of freedom of expression, though Venske spoke about how attempts to preserve free speech in the republic were often complicated or insufficient. She walked the audience through some of the influential writing and art produced before the republic’s fall to Nazism.

To conclude, Venske quoted Weimar-era author and poet Erich Kästner: “You cannot fight the avalanche once it has developed into an avalanche, you have to crush the snowball.”

Venske added: “I think that is quite a good saying for the times we are now living in, though unfortunately, he did not leave a recipe for how one could prevent this. I think we need to keep on working for it.”

Phillips, the last speaker of the evening, lamented the state of media freedom in the multiple countries where right-wing leaders have recently come to power. He mentioned specifically the rise of Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, two countries covered in the summer issue. “My time at Index has been marked not by the incredible march of progress but actually a reminder, pretty much every week, why what this organisation does is so important,” he said.

He applied Kästner’s quote to the work Index on Censorship continues to do around the globe. Like Kästner, he explained, Index works to warn the people before the snowballs represented by the arrest of a journalist or the censorship of an artwork become an avalanche of fascism.

“The avalanche starts long before you hear it,” Phillips concluded. “A large part of what we do is give the avalanche warning.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Xinran, Ahmet Altan, Stephen Woodman, Karoline Kan, Conor Foley, Robert Harris, Stefano Pozzebon and Melanio Escobar”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Judged: How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom. The summer 2019 edition of Index on Censorship magazine

The summer 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at the narrowing gap between a nation’s leader and its judges and lawyers. What happens when the independence of the justice system is gone and lawyers are no longer willing to stand up with journalists and activists to fight for freedom of expression?

In this issue Stephen Woodman reports from Mexico about its new government’s promise to start rebuilding the pillars of democracy; Sally Gimson speaks to best-selling novelist Robert Harris to discuss why democracy and freedom of expression must continue to prevail; Conor Foley investigates the macho politics of President Jair Bolsonaro and how he’s using the judicial system for political ends; Jan Fox examines the impact of President Trump on US institutions; and Viktória Serdült digs into why the media and justice system in Hungary are facing increasing pressure from the government. In the rest of the magazine a short story from award-winning author Claudia Pineiro; Xinran reflects on China’s controversial social credit rating system; actor Neil Pearson speaks out against theatre censorship; and an interview with the imprisoned best-selling Turkish author Ahmet Altan.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Judged: How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Law and the new world order by Rachael Jolley on why the independence of the justice system is in play globally, and why it must be protected

Turkey’s rule of one by Kaya Genc President Erdogan’s government is challenging the result of Istanbul’s mayoral elections. This could test further whether separation of powers exists

England, my England (and the Romans) by Sally Gimson Best-selling novelist Robert Harris on how democracy and freedom of expression are about a lot more than one person, one vote

“It’s not me, it’s the people” by Stephen Woodman Mexico’s new government promised to start rebuilding the pillars of democracy, but old habits die hard. Has anything changed?

When political debate becomes nasty, brutish and short by Jan Fox President Donald Trump has been trampling over democratic norms in the USA. How are US institutions holding up?

The party is the law by Karoline Kan In China, hundreds of human rights lawyers have been detained over the past years, leaving government critics exposed

Balls in the air by Conor Foley The macho politics of Brazil’s new president plus ex-president Dilma Rousseff’s thoughts on constitutional problems

Power and Glory by Silvia Nortes The Catholic church still wields enormous power in Spain despite the population becoming more secular

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson In Freedonia

What next for Viktor Orbán’s Hungary? Viktoria Serdult looks at what happens now that Hungary’s prime minister is pressurising the judiciary, press, parliament and electoral system

When justice goes rogue by Melanio Escobar and Stefano Pozzebon Venezuela is the worst country in the world for abuse of judicial power. With the economy in freefall, journalists struggle to bear witness

“If you can keep your head, when all about you are losing theirs…” by Caroline Muscat It’s lonely and dangerous running an independent news website in Malta, but some lawyers are still willing to stand up to help

Failing to face up to the past by Ryan McChrystal argues that belief in Northern Ireland’s institutions is low, in part because details of its history are still secret

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]Small victories do count by Jodie Ginsberg The kind of individual support Index gives people living under oppressive regimes is a vital step towards wider change[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Sending out a message in a bottle by Rachael Jolley Actor Neil Pearson, who shot to international fame as the sexist boss in the Bridget Jones’ films, talks about book banning and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on

Remnants of war by Zehra Dogan Photographs from the 2019 Freedom of Expression Arts Award fellow Zehra Doğan’s installation at Tate Modern in London

Six ways to remember Weimar by Regula Venske The name of this small town has mythic resonances for Germans. It was the home of many of the country’s greatest classical writers and gave its name to the Weimar Republic, which was founded 100 years ago

“Media attacks are highest since 1989” by Natasha Joseph Politicians in South Africa were issuing threats to journalists in the run-up to the recent elections. Now editors have built a tracking tool to fight back

Big Brother’s regional ripple effect by Kirsten Han Singapore’s recent “fake news” law which gives ministers the right to ban content they do not like, may encourage other regimes in south-east Asia to follow suit

Who guards the writers? Irene Caselli reports on journalists who write about the Mafia and extremist movements in Italy need round-the-clock protection. They are worried Italy’s deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini will take their protection away

China in their hands by Xinran The social credit system in China risks creating an all-controlling society where young people will, like generations before them, live in fear

Playing out injustice by Lewis Jennings Ugandan songwriter and politician Bobi Wine talks about how his lyrics have inspired young people to stand up against injustice and how the government has tried to silence him[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]“Watch out we’re going to disappear you” by Claudia Pineiro The horrors of DIY abortion in a country where it is still not legal are laid bare in this story from Argentina, translated into English for the first time

“Knowing that they are there, helps me keep smiling in my cell” by Ahmet Altan The best-selling Turkish author and journalist gives us a poignant interview from prison and we publish an extract from his 2005 novel The Longest Night

A rebel writer by Eman Abdelrahim An exclusive extract from a short story by a new Egyptian writer. The story deals with difficult themes of mental illness set against the violence taking place during the uprising in Cairo’s Tahrir Square[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]Index around the world – Speak out, shut out by Lewis Jennings Index welcomed four new fellows to our 2019 programme. We were also out and about advocating for free expression around the world[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Russian

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Из-за нехватки печатной бумаги в Венесуэле газеты закрываются, но онлайн СМИ развиваются быстрыми темпами, заполняя информационные дыры и донося до народа последние новости. Луис Карлос Диаз ведёт репортаж из Каракаса.

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”100973″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«Ель Импульсо», венесуэльская газета с более, чем 110-летней историей, объявила о завершении своей работы в мае, и это уже не впервые. Подобное заявление прозвучало в январе, а потом ещё одно в феврале. Всё время журналисты работали в поте лица, страницы были приготовлены и было много новостей. Единственная причина, которая остановила печать – нехватка бумаги. Эта проблема присутствует в Венесуэле уже два года. В 2013 году 10 газет закрылись. Много других сократили размер. На помощь приходят онлайн новости.

Многим газетам пришлось пересмотреть свои планы. «Ель Коррео дель Карони» сократилась с 32 до 8 страниц. «Ель Национал» уменьшила новостные сообщения, а также секцию культуры и спорта, обзор журналов и художественные приложения. Даже проправительственная газета «Диарио Вея» несколько раз заявляла, что она обречена (хотя позже её спасли).

Интернет стал местом, где свободно и спонтанно собирается информация со всей страны. В Венесуэле – стране с населением в 29 миллионов – интернет достигает только 54% жителей, но в последнее время произошёл стремительный рост в сфере цифровой индустрии, так как предприниматели пытаются привлечь новых пользователей. Новые сайты включают в свой список Poderopedia.org, который разработал в июне разочарованный журналист с целью расследования связей между политиками, бизнесменами и военными чиновниками.

«SIC», самый старый журнал страны, управляемый иезуитским политическим центром в Каракасе, решил печататься в убыток в этом году, так как пока разрабатывает цифровую стратегию. Ещё один вызов, перед которым стоит издание, это завлечение подписчиков (средний возраст которых 56 лет) в интернет. Главная разница между ситуацией в сфере средств массовой информации в Венесуэле и в остальном мире в том, что когда где-то говорят о завершении печатного журнализма, то это обычно рассуждения на тему меняющейся технологии; в Венесуэле же всё по-другому. Миграция на цифровые платформы является способом противостояния кризису нехватки бумаги.

«Андриариос», некоммерческая медиа-организация с Колумбии, спасла «Ель Импульсо», организовав срочную поставку требуемой бумаги. «Это позволило нам печататься ещё месяц», ― говорит Карлос Эдуардо Кармона, президент газеты. «Мы всё ещё выживаем день ото дня. Руководители СМИ чувствуют себя как пожарники, постоянно контролируя критические ситуации».

Инфляция в Венесуэле уже достигла критического уровня (в 2013 году она составляла 60 % согласно официальным заявлениям). Однако цена печати с июня 2013 до января 2014 возросла на 460 процентов.

Нехватка бумаги – только одна из многих особенностей Венесуэлы. Экономика, которая полностью зиждется на нефти, создала государство с пороком в самом сердце. Почти ничего не производится в стране; практически всё импортируется: лекарства, основные продукты питания и автомобильные запчасти. А эти товары не так легко закупить на международном рынке. Все закупки должны проводится государством, которое создаёт крайне сложную систему, приводящую к дефициту.

Закон про обмен валюты был принят действующим в 2003 году президентом Уго Чавезом, а это означало то, что только государство могло распоряжаться покупкой и продажей долларов. Правительство также имеет список товаров, на которые в первую очередь выделяются доллары. Но в августе 2012 года было вынесено решение убрать бумагу из этого списка, значительно увеличив тем самым её стоимость и создав сложности для тех, кто её импортирует.

Результат таких действий дал о себе знать только год спустя, когда стало очевидно, что запасы бумаги иссякли, а заголовки про дефицит туалетной бумаги в стране появились в зарубежных новостях. Ущерб для газетной индустрии был, однако, долгосрочным. Самые большие газеты страны сократили количество страниц в последующие шесть месяцев, убирая целые секции и вставки.

И хотя кризис начался с принятием государственного решения в 2012 году, ситуация усугубилась через волну протестов, которые разразились в феврале 2014 года. Ряд молодёжных демонстраций выступил с требованием сложения полномочий правительства, и эти протесты быстро переросли в ожесточённые столкновения, в которых погибло 42 человека и более чем 3,000 были задержаны. За несколько недель до бунта, журналисты и студенты-журналисты из Каракаса, Баркисимето, Сьюдад-Гуаяны выходили на демонстрации, которые сопровождались акцией в социальных сетях. «Блок де Пренса», сообщество редакторов, подсчитал, что задолженность перед поставщиками составляла как минимум $15 миллионов.

Государство в ответ централизовало закупки бумаги за день перед самым главным протестом.

В результате сейчас существует только одна структура, которая уполномочена проводить иностранные закупки бумаги. Все газеты и вся редакционная индустрия страны полагается на неё касательно своих поставок.

Кармона, из «Ель Импульсо», говорит, что запаса бумаги в стране хватает лишь на половину запроса. Вопреки практике других газет, он ещё не был вынужден поменять свою оппозиционную редакторскую позицию, но газета сократилась с 48 страниц до 12 или 16. «Мы не хотим закрываться, но мы также не хотим стать частью Пирровых СМИ с ограниченным вещанием. У меня больше нет места для репортажа. Мы вырезаем информацию, уменьшаем размер шрифта и пропуски между строками. Мы помещаем меньше фотографий. Новости телеграфические и низшего качества. Но по крайней мере, мы работаем».

Официальная статистика на закупки доллара с января по апрель 2014 обнародовала, что $7.41 миллиона было утверждено на закупку бумаги для СМИ. 85% от этой суммы ($6.3 миллиона) было предназначено для «Ультимас Нотициалс», газете с наибольшим тиражом в стране, которую купили в 2013 году за капитал, связанный с национальным правительством.

После выкупа, «Ультимас Нотициалс» сменила свою редакторскую позицию в пользу правительства. Многие ведущие журналисты газеты уволились сами, или были уволены.

Мигель Энрике Отеро, главный редактор «Ель Национал», единственной оппозиционной газеты, которая осталась в Каракасе после продажи «Ель Универсаль» в июле, говорит: «Государство прекрасно понимает потребности газет. Они знают, что утвердили валюту для закупки бумаги, но всё же деньги не выдаются по необъяснимым причинам, и нам остаётся только догадываться, что эти причины носят политический характер. Всё, что им нужно сделать, это купить медийную сеть, которая будет им прислуживать, и тогда деньги польются рекой».

Марияенграция Чиринос, информационный исследователь и член Венесуэльского института прессы и общества, убеждена, что бумажный дефицит больше влияет на читателей, чем на компании: «Информация теперь неполная. Она вынуждена находить другие места для существования и прибегать к само-публикации, что с одной стороны может быть и не плохо, но, когда это является ответной реакцией на ограничения, это может повлиять на способность граждан выбирать источники своих сведений».

В Венесуэле прослеживается очень сильная поляризация со времён coup d’etat (ред. с французского – революция) в 2002, но последние выборы в 2013 году, после смерти противоречивого лидера Уго Чавеза, ещё больше разочаровали оппозиционных активистов из-за спорного результата (разница голосов, которые принесли победу Николасу Мадуро, составила всего лишь 1.49 процента). Фернандо Гулиани, социальный психолог, говорит: «Поляризация настолько сильна, что у государственных СМИ нет места на осветление оппозиционных вопросов, будь это новости или точка зрения. Мы сожгли все мосты и больше не осталось места для диалога».

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The war of the words” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2014%2F02%2Fthe-war-of-the-words%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Our special report, starts with WWI where the current use of the term propaganda was invented and looks at poster campaigns, and propaganda journalism in the USA, but our writers also look at WWII, Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80560″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2014/02/the-war-of-the-words/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 May 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”La escasez de papel de periódico en Venezuela ha obligado a algunos periódicos a cerrar, pero los medios digitales se están expandiendo con rapidez para ocupar su lugar y mantener a la gente al tanto de las últimas noticias. Luis Carlos Díaz informa desde Caracas”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Un hombre vende periódicos en Caracas, Venezuela, FStoplight/iStock

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

En mayo, El Impulso, un periódico venezolano con más de 110 años de andadura, anunciaba su cierre. No era la primera vez. Hicieron un anuncio parecido en enero, y otro en febrero. Cada vez, los periodistas trabajaban a destajo, las páginas seguían maquetándose y había noticias de sobra. Pero algo detenía a las imprentas: no había papel.

El papel escasea en Venezuela desde hace dos años. En 2013 cerraron 10 periódicos, y muchos más han reducido su tamaño.

Los noticieros digitales están tomando el relevo y muchos periódicos han tenido que reexaminar su estrategia. El Correo del Caroni pasó de tener 32 páginas a ocho y El Nacional redujo su sección de noticias, eliminó las de cultura y deporte y se deshizo de las revistas y el suplemento literario. Hasta el Diario Vea, favorable al gobierno, anunció varias veces que estaba condenado, aunque fue rescatado más adelante.

Internet se ha convertido en el lugar donde la información procedente de todas partes del país fluye de forma más libre y espontánea. En Venezuela, un país de 29 millones de habitantes, internet solo llega al 54% de la población, pero proliferan los emprendedores digitales a medida que la gente intenta atraer a nuevos usuarios. Los ejemplos son abundantes. Entre los nuevos sitios de noticias se encuentra Poderopedia.org, lanzado en junio por un periodista de la prensa tradicional que, descontento con la situación, buscaba investigar los vínculos entre la clase política, los empresarios y los oficiales del ejército.

SIC, la revista más antigua del país, dirigida por un centro político jesuita de Caracas, ha decidido imprimir con pérdidas este año mientras trabaja en una estrategia de digitalización. La revista se enfrenta además al reto de atraer a sus suscriptores —de 56 años de media— a lo digital. La diferencia clave entre el paisaje mediático de Venezuela y el del resto del mundo es que, cuando la gente habla del fin del periodismo impreso en otros lugares, normalmente se trata de un debate sobre el cambio tecnológico; en Venezuela, es diferente. Allí, la migración a plataformas digitales es una manera de atenuar una crisis por la falta física de papel.

Fue Andiarios, una organización periodística sin ánimo de lucro de Colombia, quien rescató a El Impulso al intervenir con un envío urgente de papel. «Esto nos permitió imprimir un mes más», dice Carlos Eduardo Carmona, el presidente del diario. «Seguimos sobreviviendo día a día. Los jefes de sección se sienten como bomberos aquí, controlando emergencias constantemente».

La inflación en Venezuela ya era incapacitante (la tasa oficial en 2013 era del 60%), pero entre junio de 2013 y enero de 2014, el coste de imprimir en el país se encareció un 460%.

La carestía de papel no es más que una de las muchas peculiaridades de Venezuela. Esta economía basada en el petróleo ha formado un estado con un punto débil crónico en su mismo centro. Poco se produce de forma doméstica; casi todo es importado, incluso medicinas, alimentos básicos y recambios de automóvil. Y estos productos no se pueden comprar libremente en el mercado internacional. Todas las adquisiciones tienen que hacerse a través del estado, lo que crea un sistema extremadamente complicado que puede llevar a la escasez.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

La economía de Venezuela: cómo funciona

En 2003, el entonces presidente Hugo Chávez puso en marcha una ley de cambio de divisas internacionales que convirtió al gobierno en único administrador de la compraventa de dólares, al provenir estos de la industria estatal del petróleo. La ley estaba pensada para evitar la fuga de capitales y controlar el precio de alimentos básicos. Al mantener los dólares a un precio subvencionado por el gobierno, es más barato importar productos que producirlos en el país.

Actualmente Venezuela cuenta con cuatro tasas de cambio: la Tasa Cencoex, a 6,30 bolívares por dólar (solo para importaciones del estado); la Tasa Sicad 1, a 10 bolívares por dólar (en ventas a empresas controladas por el estado); la Tasa Sicad 2, a 50 bolívares por dólar (en ventas a ciudadanos controladas por el estado), y la tasa del mercado negro, que va de 65 a 80 bolívares por dólar: una tasa ilegal que, pese a no ser oficial, es común en la calle. El estado ha intentado centralizar todas las variables económicas, pero no le ha salido bien.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

El presidente Hugo Chávez pasó en 2003 una ley de cambio de divisas extranjeras que hace que sea el gobierno el único organismo habilitado para administrar la compraventa de dólares. Además, el gobierno también tiene una lista de productos prioritarios para los que concede el uso de dólares y en agosto de 2012 decidió eliminar al papel de la lista, incrementando los costes y las dificultades para el que intentase importarlo.

El efecto no empezó a notarse hasta un año después, cuando se hizo evidente que los suministros de papel se habían agotado y la carestía de papel higiénico a nivel nacional saltó a los titulares de todo el mundo. El daño sufrido por la industria del periódico, sin embargo, fue duradero. Los grandes diarios del país redujeron su número de páginas durante los siguientes seis meses, deshaciéndose de secciones y suplementos enteros.

Aunque fue en 2012, con la decisión del gobierno, cuando comenzó la crisis per se, esta se exacerbó por una sucesión de protestas que se iniciaron en febrero de 2014. Una serie de manifestaciones juveniles que exigían la dimisión del gobierno se tornaron rápidamente en enfrentamientos violentos, en los que hubo 42 muertos y más de 3.000 arrestos. En las semanas previas a las protestas, se habían celebrado manifestaciones de periodistas y estudiantes de periodismo en Caracas, Barquisimeto y Ciudad Guayana, acompañadas de una campaña en las redes sociales. El Bloque de Prensa, una organización de editores afiliados, calculó que existía una deuda a proveedores de al menos 15 millones de dólares estadounidenses.

El gobierno respondió centralizando la compra de papel un día antes de la protesta de más envergadura. A raíz de ello, ahora solamente existe una entidad autorizada para comprar papel al extranjero, y todos los periódicos y la industria editorial dependen de ella para obtener su suministro.

Carmona, de El Impulso, afirma que el proveedor de papel del estado solo cubre la mitad de la demanda de papel del país. Al contrario que otros periódicos, no se ha sentido presionado aún a cambiar su postura editorial oposicionista, pero el tamaño del diario sí se ha reducido de 48 páginas a 12 o 16. «No queremos cerrar, pero tampoco queremos formar parte de un conjunto mediático pírrico con presencia limitada. Ya no tengo espacio para reportajes. Hemos recortado información, reducido el tamaño de la tipografía y el interlineado. Tenemos menos imágenes y las noticias son telegráficas y de peor calidad, pero al menos seguimos funcionando».

Estadísticas oficiales sobre compras de dólares de enero a abril de 2014 revelan que se aprobaron 7,41 millones de dólares estadounidenses para papel destinado a los medios. Y el 85% de esta cantidad (6,3 millones de dólares) fue para Últimas Noticias, el periódico de mayor circulación del país, comprado en 2013 con capital vinculado al gobierno. Tras la adquisición, Últimas Noticias cambió su postura editorial a una progubernamental. Desde aquello, muchos de sus periodistas principales han dimitido o han sido despedidos.

Miguel Henrique Otero es editor jefe de El Nacional, actualmente el único periódico opuesto al gobierno en Caracas desde que El Universal se vendiera en julio. «El gobierno sabe perfectamente cuáles son las necesidades de los diarios. Saben que aprobaron divisas para comprar papel, pero no pagan por motivos desconocidos, que suponemos son políticos. Lo único que han de hacer es comprar una cadena mediática, una que se doblegue ante ellos, para que empiece a fluir el dinero», dice Otero.

Mariaengracia Chirinos, investigadora de comunicaciones y miembro del Instituto Prensa y Sociedad Venezuela, cree que la escasez de papel afecta más a los lectores que a las empresas: «La información ahora llega a medias. Tiene que recurrir a otros espacios y a la autoedición, que a veces es bueno, pero cuando es una respuesta a ciertas restricciones, también puede afectar la capacidad de la ciudadanía para elegir de dónde obtienen la información».

La polarización ha sido intensa en Venezuela desde el golpe de estado de 2002, pero las últimas elecciones en 2013, tras la muerte del divisivo líder Hugo Chávez, han acrecentado la frustración de los activistas de la oposición, al disputar los resultados (el margen de victoria de Nicolás Maduro fue solo del 1,49%). Fernando Giuliani, psicólogo social, explica que «la polarización es tan extrema que los medios del estado no dejan nada de espacio para temas de la oposición, ni en las noticias ni en opinión. Hemos quemado los puentes y ya no queda sitio para el diálogo».

Lo que Venezuela necesita por encima de todo es la puesta en marcha de canales de información que sean fiables y consigan acrecentar la fidelidad del público. Para los medios venezolanos, al ser los costes tan altos, la cantidad de lectores prima por encima de la calidad del contenido. Hoy por hoy, todos los usuarios digitales del país navegan sin ayuda por el complejo ambiente mediático, buscando el modo de procesar la información en un entorno en el que es difícil dilucidar las jerarquías que dominan las redes. Lo que tenemos no basta para enterarnos de lo que está pasando, pero sí está empoderando a la ciudadanía para decidir por sí misma.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Luis Carlos Díaz es un periodista venezolano radicado en Caracas.

This article originally appeared in the autumn 2014 issue of Index on Censorship nagazine

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Seeing the future of journalism” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2014%2F09%2Fseeing-the-future-of-journalism%2F|||”][vc_column_text]While debates on the future of the media tend to focus solely on new technology and downward financial pressures, we ask: will the public end up knowing more or less? Who will hold power to account? The subject is tackled from all angles, from our writers from across the globe.

With: Iona Craig, Taylor Walker, Will Gore[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80562″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2014/09/seeing-the-future-of-journalism/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”107175″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with best-selling author Xinran; Italian journalist and contributor to the latest issue, Stefano Pozzebon; and Steve Levitsky, the author of the New York Times best-seller How Democracies Die.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Music has long been a form of popular rebellion, especially in the 21st century. These songs, provide a theme tune to the new magazine and give insight into everything from the nationalism in Viktor Orban’s Hungary to the role of government-controlled social media in China to poverty in Venezuela![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]