26 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Letters, Magazine, News and features, Turkey Letters, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

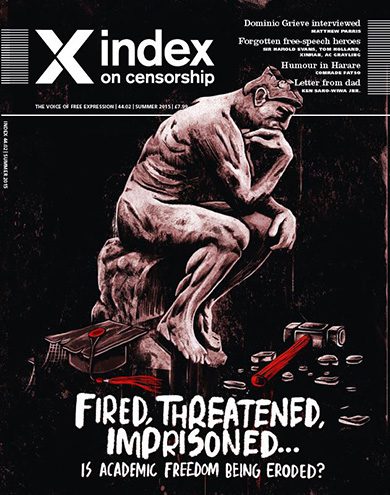

With threats ranging from “no-platforming” controversial speakers, to governments trying to suppress critical voices, and corporate controls on research funding, academics and writers from across the world have signed Index on Censorship’s open letter on why academic freedom needs urgent protection.

Academic freedom is the theme of a special report in the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine, featuring a series of case studies and research, including stories of how setting an exam question in Turkey led to death threats for one professor, to lecturers in Ukraine having to prove their patriotism to a committee, and state forces storming universities in Mexico. It also looks at how fears of offence and extremism are being used to shut down debate in the UK and United States, with conferences being cancelled and “trigger warnings” proposed to flag potentially offensive content.

Signatories on the open letter include authors AC Grayling, Monica Ali, Kamila Shamsie and Julian Baggini; Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey), Sarah Churchwell (University of East Anglia), Thomas Docherty (University of Warwick), Michael Foley (Dublin Institute of Technology), Richard Sambrook (Cardiff University), Alan M. Dershowitz (Harvard Law School), Donald Downs (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Professor Glenn Reynolds (University of Tennessee), Adam Habib (vice chancellor, University of the Witwatersrand), Max Price (vice chancellor of University of Cape Town), Jean-Paul Marthoz (Université Catholique de Louvain), Esra Arsan (Istanbul Bilgi University) and Rossana Reguillo (ITESO University, Mexico).

The letter states:

We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world from Turkey to China to the USA. In Mexico academics face death threats, in Turkey they are being threatened for teaching areas of research that the government doesn’t agree with. We feel strongly that the freedom to study, research and debate issues from different perspectives is vital to growing the world’s knowledge and to our better understanding. Throughout history, the world’s universities have been places where people push the boundaries of knowledge, find out more, and make new discoveries. Without the freedom to study, research and teach, the world would be a poorer place. Not only would fewer discoveries be made, but we will lose understanding of our history, and our modern world. Academic freedom needs to be defended from government, commercial and religious pressure.

Index will also be hosting a debate in London, Silenced on Campus, on 1 July, with panellists including journalist Julie Bindel, Nicola Dandridge of Universities UK, and Greg Lukianoff, president and CEO of Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, US.

To attend for free, register here.

If you would like to add your name to the open letter, email [email protected]

A full list of signatories:

Professor Mike Adams, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, USA

Monica Ali, author

Lyell Asher, associate professor, Lewis & Clark College, USA

Professor Jim Al-Khalili OBE, University of Surrey, UK

Esra Arsan, associate professor, Istanbul Bilgi University, Turkey

Julian Baggini, author

Professor Mark Bauerlein, Emory University, USA

David S. Bernstein, publisher, USA

Robert Bionaz, associate professor, Chicago State University, USA

Susan Blackmore, visiting professor, University of Plymouth, UK

Professor Jan Blits, professor emeritus, University of Delaware, USA

Professor Enikö Bollobás, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Professor Roberto Briceño-León, LACSO, Caracas, Venezuela

Simon Callow, actor

Professor Sarah Churchwell, University of East Anglia, UK

Professor Martin Conboy, University of Sheffield, UK

Professor Thomas Cushman, Wellesley College, USA

Professor Antoon De Baets, University of Groningen, Holland

Professor Alan M Dershowitz, Harvard Law School, USA

Rick Doblin, Association for Psychedelic Studies, USA

Professor Thomas Docherty, University of Warwick, UK

Professor Donald Downs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA

Professor Alice Dreger, Northwestern University, USA

Michael Foley, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Professor Tadhg Foley, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

Nick Foster, programme director, University of Leicester, UK

Professor Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

AC Grayling, author

Professor Randi Gressgård, University of Bergen, Norway

Professor Adam Habib, vice-chancellor, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Professor Gerard Harbison, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Adam Hart Davis, author and academic, UK

Professor Jonathan Haidt, NYU-Stern School of Business, USA

John Earl Haynes, retired political historian, Washington, USA

Professor Gary Holden, New York University, USA

Professor Mickey Huff, Diablo Valley College, USA

Professor David G. Hoopes, California State University, USA

Philo Ikonya, poet

James Ivers, lecturer, Eastern Michigan University, USA

Rachael Jolley, editor, Index on Censorship

Lee Jones, senior lecturer, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Stephen Kershnar, distinguished teaching professor, State University of New York, Fredonia, USA

Professor Laura Kipnis, Northwestern University, USA

Ian Kilroy, lecturer, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

Val Larsen, associate professor, James Madison University, USA

Wendy Law-Yone, author

Professor Michel Levi, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Ecuador

Professor John Wesley Lowery, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA

Greg Lukianoff, president and chief executive, Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire), USA

Professor Tetyana Malyarenko, Donetsk State Management University, Ukraine

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director, Sage

Charlie Martin, editor PJ Media, UK

Jean-Paul Marthoz, senior lecturer, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium

Professor Alan Maryon-Davis, King’s College London, UK

John McAdams, associate professor, Marquette University, USA

Timothy McGuire, associate professor, Sam Houston State University, USA

Professor Tim McGettigan, Colorado State University, USA

Professor Lucia Melgar, professor in literature and gender studies, Mexico

Helmuth A. Niederle, writer and translator, Germany

Professor Michael G. Noll, Valdosta State University, USA

Undule Mwakasungula, human rights defender, Malawi

Maureen O’Connor, lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Professor Niamh O’Sullivan, curator of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, and Quinnipiac University, Connecticut, USA

Behlül Özkan, associate professor, Marmara University, Turkey

Suhrith Parthasarathy, journalist, India

Professor Julian Petley, Brunel University, UK

Jammie Price, writer and former professor, Appalachian State University, USA

Max Price, vice-chancellor, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Clive Priddle, publisher, Public Affairs

Professor Rossana Reguillo, ITESO University, Mexico

Professor Glenn Reynolds, University of Tennessee College of Law, USA

Professor Matthew Rimmer, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Professor Paul H. Rubin, Emory University, USA

Andrew Sabl, visiting professor, Yale University, USA

Alain Saint-Saëns, director,Universidad Del Norte, Paraguay

Professor Richard Sambrook, Cardiff University, UK

Luís António Santos, University of Minho, Portugal

Professor Francis Schmidt, Bergen Community College, USA

Albert Schram, vice chancellor/CEO, Papua New Guinea University of Technology

Victoria H F Scott, independent scholar, Canada

Kamila Shamsie, author

Harvey Silverglate, lawyer and writer, Massachusetts, USA

William Sjostrom, director and senior lecturer, University College Cork, Ireland

Suzanne Sisley, University of Arizona College of Medicine, USA

Chip Stewart, associate dean of the Bob Schieffer College of Communication, Texas Christian University, USA

Professor Nadine Strossen, New York Law School, USA

Professor Dawn Tawwater, Austin Community College, USA

Serhat Tanyolacar, visiting assistant professor, University of Iowa, USA

Professor John Tooby, University of California, USA

Meena Vari, Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore, India

Professor Leland Van den Daele, California Institute of Integral Studies, USA

Professor Eugene Volokh, UCLA School of Law, USA

Catherine Walsh, poet and teacher, Ireland

Christie Watson, author

Ray Wilson, author

Professor James Winter, University of Windsor, Canada

22 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Counter Terrorism, Magazine, United Kingdom, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

Students at a protest in Manchester. Photo: Alamy/ M Itani

The realisation of academic freedom typically depends on controversy: it voices dissent. Linked to free speech, it is marked primarily by critique, speaking against – even offending against – prevailing or accepted norms. If it is to be heard, to make a substantial difference, such speech cannot be entirely divorced from rules or law. Yet legitimate rule – law – is itself established through talk, discussion and debate. Academic freedom seeks a new linguistic bond by engaging with or even producing a free assembly of mutually linked speakers. To curb such freedom, you delegitimise certain speakers or forms of speech; and the easiest way to do this is to isolate a speaker from an audience and to isolate members of an audience from each other. Silence the speaker; divide and rule the audience. When that seems extreme, work surreptitiously: attack not what is said but its potentially upsetting or offensive “tone”. Such inhibitions on speech increasingly chill conditions on campus.

Academic freedom is typically enshrined in university statutes, a typical formulation being that “academic staff have freedom within the law to question and test received wisdom, and to put forward new ideas and controversial or unpopular opinions, without placing themselves in jeopardy of losing their jobs or privileges” – as the statutes of the University of Warwick, where I work, have it. Yet academic freedom is now being fundamentally weakened and qualified by legislation, with which universities must comply.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, speaking in Munich on 5 February 2011, said: “We must stop these groups [terrorists] from reaching people in publicly funded institutions like universities.” This was followed by a UK government report on tackling extremism, released ahead of the recent election, which said: “Universities must take seriously their responsibility to deny extremist speakers a platform.” It was suggested that “Prevent co-ordinators” could “give universities access to the information they need to make informed decisions” about who they allowed to speak on campuses. Ahead of May’s UK election university events had already been changed or cancelled. And immediately after the election, the government signalled its intention to focus further on the extremism agenda. In endorsing this approach, university vice-chancellors have acquiesced in a too-intimate identification of the interests of the search for better argument with whatever is stated as government policy. The expectation is that academics will in turn give up the autonomy required to criticise that policy or those who now manage it on government’s behalf in our institutions.

Governments worldwide increasingly assert the legal power to curtail the free speech and freedom of assembly that is axiomatic to the existence of academic freedom. This endangers democracy itself, what John Stuart Mill called “governance by discussion”. The economist Amartya Sen, for example, has recently resigned from his position as chancellor of Nalanda University in India because of what he saw as “political interference in academic matters” whereby “academic governance in India remains … deeply vulnerable to the opinions of the ruling government”. (See our report from India in our academic freedom special issue.) This is notable because it is one extremely rare instance of a university leader taking a stand against government interference in the autonomous governance of universities, autonomy that is crucial to the exercise of speaking freely without jeopardy.

Academic freedom, and the possibilities it offers for democratic assembly in society at large, now operates under the sign of terror. This has empowered governments to proscribe not just terrorist acts but also talk about terror; and governments have identified universities as a primary location for such talk. Clearly closing down a university would be a step too far; but just as effective is to inhibit its operation as the free assembly of dissenting voices. We have recently wit- nessed a tendency to quarantine individuals whose voices don’t comply with governance/ government norms. Psychology professor Ian Parker was suspended by Manchester Metropolitan University and isolated from his students in 2012, charged with “serious misconduct” for sending an email that questioned management. In 2014, I myself was suspended by the University of Warwick, barred from having any contact with colleagues and students, barred from campus, prevented from attending and speaking at a conference on E P Thompson, and more. Why? I was accused of undermining a colleague and asking critical questions of my superiors, the answers to which threatened their supposedly unquestionable authority. None of these charges were later upheld at a university tribunal.

More insidious is the recourse to “courtesy” as a means of preventing some speech from enjoying legitimacy and an audience. Several UK institutions have recently issued “tone of voice” guidelines governing publications. The University of Manchester, for example, says that “tone of voice is the way we express our brand personality in writing”; Plymouth University argues that “by putting the message in the hands of the communicator, it establishes a democracy of words, and opens up new creative possibilities”. These statements should be read in conjunction with the advice given by employment lawyer David Browne, of SGH Martineau (a UK law firm with many university clients). In a blogpost written in July 2014, he argued that high-performing academics with “outspoken opinions”, might damage their university’s brand and in it made comparisons between having strong opinions and the behaviour of footballer Luis Suárez in biting another player during the 2014 World Cup. The blog was later updated to add that its critique only applied to opinions that “fall outside the lawful exercise of academic freedom or freedom of speech more widely”, according to the THES (formerly the Times Higher Education Supplement). Conformity to the brand is now also conformity to a specific tone of voice; and the tone in question is one of supine compliance with ideological norms.

This is increasingly how controversial opinion is managed. If one speaks in a tone that stands out from the brand – if one is independent of government at all – then, by definition, one is in danger of bringing the branded university into disrepute. Worse, such criticism is treated as if it were akin to terrorism-by-voice.

Nothing is more important now than the reassertion of academic freedom as a celebration of diversity of tone, and the attendant possibility of giving offence; otherwise, we become bland magnolia wallpaper blending in with whatever the vested interests in our institutions and our governments call truth.

This vested interest – especially that of the privileged or those in power – now parades as victim, hurt by criticism, which it calls of- fensive disloyalty. What is at issue, however, is not courtesy; rather what is required of us is courtship. As in feudal times, we are legitimised through the patronage of the obsequium that is owed to the overlords in traditional societies.

Academic freedom must reassert itself in the face of this. The real test is not whether we can all agree that some acts, like terrorism, are “barbaric” in their violence; rather, it is whether we can entertain and be hospitable to the voice of the foreigner, of she who thinks – and speaks – differently, and who, in that difference, offers the possibility of making a new audience, new knowledge and, indeed, a new and democratic society, governed by free discussion.

© Thomas Docherty

Thomas Docherty is professor of English and of comparative literature at the University of Warwick in the UK.

This article is part of a special issue of Index on Censorship magazine on academic freedom, featuring contributions from the US, Ukraine, Belarus, Mexico, India, Turkey and Ireland. Subscribe to read the full report, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

9 Jun 2015 | Academic Freedom, Magazine, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

Illinois Urbana-Champaign University in the United States, where one academic had his job offer withdrawn over his tweets on the Israel-Gaza conflict. Credit: Alamy/ Jeff Greenberg

This article is taken from the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine (volume 44, issue 2). To read the full report on academic freedom, subscribe or download the app on a free trial

The power of Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible continues to resonate in 2015. London’s Old Vic revived the play by Miller, a long-time supporter of Index, this year, and it has never seemed more chilling. As characters threw accusation and counter accusation at each other across the stage, the words felt just as relevant to the zip of the social-media age as to Salem in 1692.

In Ukraine, as our report in this issue details, attestation committees have now been set up to examine accusations by students and others that university academics might have “separatist attitudes” or have been using “provocative” speech. If found guilty lecturers can lose their jobs. This forms part of the brooding atmosphere currently hanging over Ukraine’s academic life, where former colleagues are banned from speaking to each other, and a system of national “patriotic” education has been introduced.

But Ukraine is not alone. In Belarus, a national committee acts casts a judgemental eye on any university that shows independence of spirit, or might choose to teach subjects in a way that the authoritarian government might find unsettling. And in Turkey, the nationwide YÖK committee stands disapprovingly on the sidelines, interfering in the minutiae of academic dress sense, giving orders about the wearing of headscarves and beards, as well as recently issuing a rule that academics should not give their opinions to the media, except on scientific subjects.

Around Turkey academic freedom is coming under attack from all sides, one lecturer who put a question about a Kurdish manifesto written in the 1970s on an exam paper, received multiple death threats and was accused of being “a terrorist”.

One hundred years ago the Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure was published in the USA, a century on, university faculty are still finding that institutions disapprove of them having public opinions on political issues. While some US universities restrict freedom of expression on campuses to painted-square zones, presumably where students can cope with hearing opinions they disagree with, faculty members are expected not to be outspoken on social media, or find themselves, as in the case of Steven Salaita (detailed in the magazine), having their assistant professorship job offer withdrawn.

Universities should be places where discoveries are made. Academia is an opportunity for students and teachers to challenge themselves; their preconceptions and values, and, perhaps, head off in a new direction. Studying can be the start of something big; a new idea that might end in an enormously valuable invention such as the Large Hadron Collider; or it might just be a big moment for the individual, who discovers a fascination for medieval history, or 8th-century literature.

Education opens up all sorts of avenues of discovery, but if we start closing some of those roads off, arguing they are too dangerous, or challenging, or hold possible stress, then we are heading off in a terrifying direction. For this issue of the magazine, we found academics, authors and activists around the world were worried enough to support the following statement:

“We the undersigned believe that academic freedom is under threat across the world from Turkey to China to the USA. In Mexico academics face death threats, in Turkey they are being threatened for teaching areas of research that the government doesn’t agree with. We feel strongly that the freedom to study, research and debate issues from different perspectives is vital to growing the world’s knowledge and to our better understanding. Throughout history, the world’s universities have been places where people push the boundaries of knowledge, find out more, and make new discoveries. Without the freedom to study, research and teach, the world would be a poorer place. Not only would fewer discoveries be made, but we will lose understanding of our history, and our modern world. Academic freedom needs to be defended from government, commercial and religious pressure.”

A full list of signatures can be seen here, with supporters including authors AC Grayling, Monica Ali, Kamila Shamsie and Julian Baggini; Jim Al-Khalili (University of Surrey), Sarah Churchwell (University of East Anglia), Thomas Docherty (University of Warwick), Michael Foley (Dublin Institute of Technology), Richard Sambrook (Cardiff University), Alan M. Dershowitz (Harvard Law School), Donald Downs (University of Wisconsin-Madison), Professor Glenn Reynolds (University of Tennessee), Adam Habib (vice chancellor, University of the Witwatersrand), Max Price (vice chancellor, University of Cape Town), Jean-Paul Marthoz (Université Catholique de Louvain), Esra Arsan (Istanbul Bilgi University) and Rossana Reguillo (ITESO University, Mexico).

The range of signatures from countries around the globe show just how far and wide the fear is that academic freedom is, in 2015, coming under enormous pressure.

© Rachael Jolley

This article comes from the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine (volume 44, issue 2), which contains features from across the world, plus fiction and poetry by writers in exile. Subscribe or download the app (free trial) to read the magazine in full. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

Students and academics at 7500 universities around the globe have access to the magazine’s archive containing 43 years of articles via Sage.

Subscribers can read Arthur Miller in Index on Censorship magazine here.