19 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Arabic

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”يعتمد الكثير من المراسلين الأجانب على “أدلّاء“ صحفيين (Fixers) لمساعدتهم على تغطية مناطق الصراع. ولكن، كما تكشف كارولين ليس، يتعرّض هؤلاء الأشخاص في أحيان كثيرة للاستهداف كـ“جواسيس“ عندما تكشف أسمائهم الحقيقية محليا”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

صحفيون أوكرانيون في مؤتمر صحفي عقد بالسفارة الأمريكية, US Embassy Kiev Ukraine/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

يخاطر رواند بحياته بشكل متكرّر من أجل أشخاص لا يعرفهم. فطالب علوم الكمبيوتر البالغ من العمر 25 عاما يعمل بشكل مواز كـ”دليل” صحفي محلّي يساعد المراسلين الأجانب، في أربيل بالعراق. تبعد المدينة مسافة ساعة واحدة فقط عن الموصل، التي يحتلّها تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية (داعش). كان التنظيم قد هدّد في شهر يونيو/حزيران بقتل الصحفيين الذين “يحاربون ضد الإسلام”.

يقول رواند الذي عمل سابقا مع مجلة “فيس نيوز” و “تايم”: “دعونا نتخيّل أن داعش أتت إلى أربيل، فأول الناس الذين سوف يبحثون عنهم هم الأدلّاء الصحفيون”. ويضيف “بعد كل تقرير فإن الدليل يبقى في البلاد، في حين أن لدى المراسل جواز سفر أجنبي ويمكنه أن يغادر” البلاد عندما يشاء.

ويقوم الأدلّاء بتوّلي الخدمات اللوجستية للمراسلين الأجانب، بما فيها الترجمة والتوجيه، ولكنهم يقومون أيضا بالبحث وجمع المصادر، وترتيب المقابلات، والذهاب إلى الخطوط الأمامية. معظمهم هم من العاملين لحسابهم الخاص، وهم معرّضون بشدّة للتهديدات والأعمال الانتقامية، خاصة عندما يغادر زملاؤهم الأجانب. فطبقا لمنظمة روري بيك تروست، وهي منظمة تدعم العاملين لحسابهم الخاص في جميع أنحاء العالم، فإن عدد الصحفيين المحليين المستقلين الذين يتم استهدافهم بسبب عملهم في مساعدة الإعلام الدولي قد ازداد بشكل كبير في الآونة الأخيرة.

تقول مولي كلارك، مديرة الاتصالات في روري بيك: “إن غالبية طلبات المساعدة تأتينا من الصحفيين المحليين المستقلين الذين يتعرضون للتهديد أو الاحتجاز أو السجن أو الاعتداء أوالإبعاد القسري بسبب عملهم”. وتضيف “نحن نقوم بشكل منتظم بدعم أولئك الذين يتم استهدافهم بسبب عملهم مع وسائل الإعلام الدولية. ففي هذه الحالات يمكن أن تكون العواقب مدمرة وطويلة الأجل – ليس فقط بالنسبة لهم ولكن لعائلاتهم أيضا “.

وتفيد لجنة حماية الصحفيين أن 94 “من العاملين في الإعلام” كانوا قد قتلوا منذ 2003، العام الذي بدأت فيه لجنة حماية الصحفيين بتصنيف الأدلّاء في خانة منفصلة تقديرا منها لأهميتهم المتزايدة في التقارير الإخبارية الأجنبية. وفي حزيران / يونيو من هذا العام، أضافة لجنة حماية الصحفيين زبي الله تامانا، وهو صحفي أفغاني مستقلّ يعمل كمترجم لإذاعة إن.بي.أر في الولايات المتحدة، إلى قائمة أولئك الذين قتلوا في تفجير استهدف قافلة كان يتنقّل معها في أفغانستان

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

یبدأ العدید من الأدلّاء مسيرتهم كهواة قليلي الخبرة ویائسين للحصول على عمل مدفوع الأجر، عادة في دول ذات اقتصادات متضرّرة بسبب الحرب. وهم نادرا ما يحصلون على تدريب أو دعم طويل الأجل من قبل المنظمات الدولية التي يعملون من أجلها، وغالبا ما يكونون مسؤولين بأنفسهم عن سلامتهم الشخصية. تعلّم رواند أن يخفي هويته في أربيل ونادرا ما يضع اسمه في تقرير أو مادة يساهم فيها. “إن إرفاق اسمي بالتقارير يعني أنني لست مجهول الهوية. قد يؤدّي ذلك الى شكوك حولي وقد أعامل كجاسوس “.

تلقّي الاتهامات بالتجسس يشكل خطرا مهنيا بالنسبة للعديد من الأدلّاء الذين يعملون مع الصحفيين الأجانب. بالنسبة لأولئك الذين يعملون على الجبهة بين أوكرانيا والانفصاليين المدعومين من روسيا، مثلا، يشكّل هذا الاتهام تهديدا يوميا. ففي عام 2014، اختطف انطون سكيبا، وهو منتج محلي من دونيتسك، من قبل الانفصاليين واتهم بأنه جاسوس أوكراني. وكان قد قضى اليوم فى العمل لصالح شبكة سي ان ان في الموقع الذى تحطمت فيه طائرة تابعة للخطوط الجوية الماليزية رحلة MH17 في شرق اوكرانيا التي يسيطر عليها الانفصاليون. وقد أطلق سراح سكيبا، الذي عمل أيضا مع هيئة الإذاعة البريطانية، في نهاية المطاف، بعد حملة قام بها زملاؤه. وقال “من المهم حقا ان نبقى متوازنين عندما يكون لدينا القدرة الى الوصول الى كلا الجانبين، والا فان هناك احتمال كبير ان يتم قمعنا من قبل احد الطرفين”.

يحاول سكيبا حماية نفسه من خلال الحرص على الناس الذين يعمل معهم والمواضيع التي يغطّيها. يقول “هذا بلدي حيث سوف أستمر بالعيش هنا بعد أن ينتقل الصحفيون إلى تغطية صراع آخر. لا أريد المخاطرة بحياتي من أجل موضوع قد يتم نسيانه في اليوم التالي. لهذا السبب، أحاول تجنّب الصحفيين غير المحترفين والذين يستغلّون الأدلّاء الوصول الى المواضيع “الساخنة”.”

أما كاترينا، وهي دليل آخر من منطقة دونيتسك، فقد حصلت على اعتماد صحفي من كل من السلطات الأوكرانية وجمهورية دونيتسك الشعبية الانفصالية لتجنب الاتهامات بتفضيل طرف واحد على الأخر. ولكن هذا لم يوقف التهديدات والمضايقات ضدها. ففيما لا تعلن كاترينا أنها تعمل مع صحفيين دوليين، قام موقع أوكرانيا على شبكة الإنترنت، وهو “ميروفيتورس”، قام مؤخرا بالكشف عن أسماء وعناوين بريد إلكتروني وأرقام هواتف حوالي 5000 صحفي أجنبي ومحلي عملوا في وجمهورية دونيتسك الشعبية وفي لوهانسك – وهي مناطق انفصالية لا تسيطر عليها الحكومة الأوكرانية. ظهر اسم كاترينا، 28 عاما، عدة مرات في هذه القائمة، التي نشرت في مايو 2016، لأنها عملت مع بي بي سي، وشبكة الجزيرة ووسائل إعلام أخرى.

وقد تم احتجاز كاترينا عدّة مرّات واستجوابها من قبل أجهزة الأمن الأوكرانية بسبب عملها. تقول “بعد عامين من العمل مع وسائل الاعلام الاجنبية أصبحت في دائرة الضوء الامنية”. وتضيف “من الأفضل عدم الاستهانة بقوتهم. فهم أذكياء بما فيه الكفاية للتلاعب بحياتك.”

تقول كاترينا انها تشعر الآن بأنها معرّضة للخطر في دونيتسك وترغب في الانتقال الى عمل آخر. تقول: “بمجرد مغادرة طاقم التلفزيون، ينتهي كل شيء…مرة واحدة فقط شعرت بالاهتمام من قبل وسائل الإعلام الدولية. ففي مايو / أيار، سألني أحد زملائي في هيئة الإذاعة البريطانية عما إذا كنت بحاجة إلى الدعم بعد نشر اسمي على ميرتفوريتس. رفضت أي مساعدة لأن نشر اسمي كان أقل ما يمكن أن يحدث لي”.

هناك عدد قليل جدا من الأدلّاء الصحفيين مؤهلين للحصول على تعويضات إذا ما أصيبوا أو قتلوا أثناء العمل. كما أنهم لا يتمتعون بالحماية الدولية التي تمنح عمليا إلى الصحفيين الأجانب العاملين في الخارج. في أفغانستان وحدها، قتل عشرات المترجمين والسائقين والمنتجين المحليين بين عامي 2003 و 2011، بعضهم في ساحات القتال، وآخرين، مثل الصحفي أجمل نقشبندي والسائق سيد آغا، أعدمتهم جماعة طالبان بتهمة العمل مع أجانب.

بدورها، فإن سايرة، وهي دليل صحفي عملت في كابول بأفغانستان خلال السنوات التسع الماضية، لا تستطيع أن تعمل إلا إذا أخفت ليس فقط هويتها، بل نفسها أيضا. كامرأة فهي تتعرض باستمرار للتهديد وإساءة المعاملة. وبدت خائفة جدا من الانتقام لو أعطت اسمها الحقيقي من أجل هذا التقرير. وقالت الامرأة البالغة من العمر 26 عاما، التي كانت قد بدأت بالعمل مع الصحفيين الاجانب للمساعدة في تمويل دراستها في جامعة كابول، قالت انها تشعر فقط بالأمان عندما يكون وجهها منقّب. “لقد سافرت إلى بعض الأماكن الخطرة مع الصحفيين الأجانب. كان علي أن أغطى وجهي بالبرقع لكي أشعر بالأمان”. وتضيف: “هناك دائما أخطارا على المرأة التي تعمل، حتى في كابول، فإنها قد تتلقى تعليقات مسيئة من المجتمع وتقفد الاحترام. كثير من الناس يلومونك وحتى يتهمّوك بالكفر اذا كنت تعمل مع شخص غير مسلم”.

لقد ازدادت ظاهرة توظيف الأدلاء الصحفيين في المناطق التي تعتبر خطرة جدا بالنسبة للمراسلين الأجانب، لكتابة وإرسال التقارير مباشرة الى وسائل الإعلام الدولية. وتقول كلارك: “هناك اعتماد متزايد على العاملين لحسابهم الخاص في مجال الأخبار والصور في البلدان والمناطق الخطرة أو تلك التي يكون من الصعب [للمراسلين الدوليين] الوصول إليها. وتضيف “ليس لدينا أي حقائق أو أرقام محددة، فإن أدلتنا في الغالب تأتي من ما نسمعه ونلاحظه من خلال عملنا”.

كان المقداد مجلي يعمل دليلا صحفيا ثم أصبح مراسلا عندما أجبرت الحرب في اليمن العديد من الأجانب على مغادرة البلاد. كان مجلي، 34 عاما، يتحدث الإنجليزية جيّدا، ولديه علاقات واسعة، وتمتّع بالاحترام وكان هناك طلب كبير على خدماته. فضل مجلي العمل دون الكشف عن هويته. تقول لورا باتاغليا، الصحفية الإيطالية التي عملت معه وأصبحت صديقة له فيما بعد: “كان يحب العمل كدليل صحفي لأن ذلك سمح له بإخبار القصص التي لا يستطيع أن يرويها بأمان في اليمن”. وتضيف: “بالاتفاق معه، كنا نخفي اسمه من المقالات الصعبة لحمايته”.

ولكن عندما بدأ مجلي في تغطية الأخبار بمفرده، واجه مشاكل مع ميليشيا الحوثيين، وهي جماعة متمرّدة تسيطر على صنعاء، عاصمة اليمن. أغضبت مقالته الأولى التي أرسلها الى الصحف الإخبارية في أوروبا والولايات المتحدة تحت اسمه الجهات الحاكمة فورا، فألقي القبض عليه وتم تهديده من قبل عملاء الحكومة. وفي كانون الثاني / يناير من هذا العام، قتل في غارة جوية أثناء تغطيته الأحداث لإذاعة فويس أوف أمريكا. كان يتنقّل في منطقة خطرة في سيارة لا تحمل ايّ علامات تشير إلى أنه صحفي.

أثار مصرع مجلي أسئلة تتعلق بتوزيع المسؤولية. فعلى الرغم من أنه كان يعمل على حسابه الخاص، كان عمله في النهاية يصبّ في مجال المنظمات الإعلامية الدولية. يعتقد مايك غارود، المؤسس المشارك لـ”وورد فيكسر”، وهي شبكة على الانترنت تربط الصحفيين المحليين والمستقلّين مع المراسلين الدوليين، أن بعض الجماعات الإعلامية بدأت تلعب دورها بجديّة أكبر لضمان سلامة العاملين لحسابهم الخاص الذين تتعامل معهم.

يخطّط غارود لإعداد برنامج تدريبي عبر الإنترنت للصحفيين والأدلّاء المحليين. وستشمل الدورة تقييم المخاطر، والأمن، والمعايير الصحفية والأخلاقيات. يقول “الأدلّاء هم إلى حد كبير غير مدرّبون وهم معرّضون للخطر في البيئات المعادية. وبما أن خدمات الأدلّاء قد توّسعت خارج نطاق الترجمة والخدمات “فهناك حاجة حقيقية لأن يفهموا ويدركوا مفاهيم معينة”، يضيف غارود. وقد سئلنا شبكات بي بي سي و سي إن إن ورويترز عن سياساتهم الخاصة حول استخدام الأدلّاء ولكنهم رفضوا الادلاء بأي تعليق.

بحسب غارود، فإن تنظيم سلوك الصحفيين الذين يستخدمون الأدلّاء في الحقل يبقى صعبا. ويذكر هنا قصة طالب شاب، استأجره مراسل أجنبي للذهاب إلى خط الجبهة في العراق عندما كان عمره 17 عاما. “هناك الكثير مما يمكن أن يفعله القطاع لتشجيع الصحفيين على التصرف بشكل أكثر مسؤولية فيما يتعلق بهذه المسألة، ولكن ما يقلقني هو غياب الإرادة للتدقيق في الكيفية التي يتم بها جمع المعلومات من أجل التقارير”.

من جهته، عمل ضياء الرحمن ، 35 عاما، مع مراسلين أجانب في كراتشي، باكستان، بين عامي 2011 و 2015. ويقول أنه بخلاف الصحفيين المحليين في المدينة الذين يفهمون المخاطر التي تواجه الصحفيين هناك، فهناك بعض الصحفيين الأجانب الذين يتجاهلون نصيحتهم. يقول “بعض المصورين لديهم طباع سيئة وهم وقحون ويعاملون الأدلّاء كأنهم خدم. بما انهم لا يعرفون تعقيدات وحساسية الوضع، فهم يقومون بتصوير افلام أو التقاط الصور دون استشارة الأدلّاء، مما تسبب بمشاكل كبيرة للفريق، لا سيما للأدلاء”.

في بعض الحالات، اختطف أدلّاء وضربوا وتعرّضوا للتعذيب على أيدي أجهزة الأمن الباكستانية بسبب عملهم مع صحفيين أجانب. وقال رحمن انه نادرا ما يعمل كدليل صحفي الآن، ولا يتعامل الا مع مراسلين يعرفهم عن كثب.

انه من الضروري أن يتم تقديم المزيد من التدريب والدعم من قبل المنظمات الدولية التي تستخدم الأدلّاء من أجل سلامتهم، ولكنه يظل من غير المرجح أن يحدث هذا فرقا في المناطق التي ما زال يسيطر عليها تنظيم داعش، الذي يصمم على إسكات الصحفيين، خاصة أولئك الذين يعملون مع المؤسسات الأجنبية. في يونيو/حزيران من هذا العام، ذكرت لجنة حماية الصحفيين أن تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية أعدم خمسا من الصحفيين المستقلين في سوريا. تم ربط احدهم بجهاز الكمبيوتر المحمول الخاص به، وآخر إلى كاميرته، بعد أن تم تفخيخهما ثم فجرّت بهم. وقد اتهموا بالعمل مع مؤسسات الأخبار ومنظمات حقوق الإنسان الأجنبية. نشرت داعش تسجيلا للإعدام لكي يكوم أمثولة وتحذيرا للآخرين.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

)تم تغيير بعض الأسماء في هذه المقالة لأسباب أمنية (

كارولين ليز مراسلة سابقة لصحيفة صنداي تايمز البريطانية في جنوب آسيا. وتعمل حاليا كباحثة مع معهد رويترز لدراسة الصحافة في جامعة أكسفورد

*ظهر هذا المقال أولا في مجلّة “اندكس أون سنسورشيب” بتاريخ ٢٠ سبتمبر/أيلول ٢٠١٦

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Oct 2016 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, Bangladesh, Burma, India, mobile, News, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tibet

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines, Himal Southasian, is to close next month after 29 years of publishing as part of a clampdown on freedom of expression across the region. The magazine has a specific goal: to unify the divided countries in South Asia by informing and educating readers on issues that stretch throughout the region, not just one community.

Index got a chance to speak with Himal Southasian’s editor, Aunohita Mojumdar, on the vital role of independent media in South Asia, the Nepali government’s complicated way of silencing activists and what the future holds for journalism in the region.

“The means used to silence us are not straightforward but nor are they unique,” Mojumdar said. “Throughout the region one sees increasing use of regulatory means to clamp down on freedom of expression, whether it relates to civil society activists, media houses, journalists or human rights campaigners.”

Himal Southasian, which claims to be the only analytical and regional news magazine for South Asia, faced months of bureaucratic roadblocks before the funding for the magazine’s publisher, the Southasia Trust, was cut off due to non-cooperation by regulatory state agencies in Nepal, said the editor. This is a common tactic among the neighbouring countries as governments are wary of using “direct attacks or outright censorship” for fear of public backlash.

But for Nepal it wasn’t always this way. “Nepal earlier stood as the country where independent media and civil society not accepted by their own countries could function fearlessly,” Mojumdar said.

In a statement announcing its suspension of publication as of November 2016, Himal Southasian explained that without warning, grants were cut off, work permits for editorial staff became difficult to obtain and it started to experience “unreasonable delays” when processing payments for international contributors. “We persevered through the repercussions of the political attack on Himal in Parliament in April 2014, as well as the escalating targeting of Kanak Mani Dixit, Himal’s founding editor and Trust chairman over the past year,” it added.

Index on Censorship: Why is an independent media outlet like Himal Southasian essential in South Asia?

Aunohita Mojumdar: While the region has robust media, much of it is confined in its coverage to the boundaries of the nation-states or takes a nationalistic approach while reporting on cross-border issues. Himal’s coverage is based on the understanding that the enmeshed lives of almost a quarter of the world’s population makes it imperative to deal with both challenges and opportunities in a collaborative manner.

The drum-beating jingoism currently on exhibit in the mainstream media of India and Pakistan underline how urgent it is for a different form of journalism that is fact-based and underpinned by rigorous research. Himal’s reportage and analysis generate awareness about issues and areas that are underreported. It’s long-form narrative journalism also attempts to ensure that the power of good writing generates interest in these issues. Based on a recognition of the need for social justice for the people rather than temporary pyrrhic victories for the political leaderships, Himal Southasian brings journalism back to its creed of being a public service good.

Index: Did the arrest of Kanak Mani Dixit, the founding editor for Himal Southasian, contribute to the suspension of Himal Southasian or the treatment the magazine received from regulatory agencies?

Mojumdar: In the case of Himal or its publisher the non-profit Southasia Trust, neither entity is even under investigation. We can only surmise that the tenuous link is that the chairman of the trust, Kanak Mani Dixit, is under investigation since we have received no formal information. Informally we have indeed been told that there is political pressure related to the “investigation” which prevents the regulatory bodies from providing their approval.

The lengthy process of this denial – we had applied in January 2016 for the permission to use a secured grant and in December 2015 for the work permit, effectively diminished our ability to function as an organisation until the point of paralysis. While the case against Dixit is itself contentious and currently sub judice, Himal has not been intimated by any authority that it is under any kind of scrutiny. On the contrary, regulatory officials inform us informally that we have fulfilled every requirement of law and procedure, but cite political pressure for their inability to process our requests. Our finances are audited independently and the audit report, financial statements, bank statements and financial reporting are submitted to the Nepal government’s regulatory bodies as well as to the donors.

Index: Why is Nepal utilising bureaucracy to indirectly shut down independent media? Why are they choosing indirect methods rather than direct censorship?

Mojumdar: The means used to silence us are not straightforward but nor are they unique. Throughout the region one sees increasing use of regulatory means to clamp down on freedom of expression, whether it relates to civil society activists, media houses, journalists or human rights campaigners. Direct attacks or outright censorship are becoming rarer as governments have begun to fear the backlash of public protests.

Index: With the use of bureaucratic force to shut down civil society activists and media growing in Nepal, how does the future look for independent media in South Asia?

Mojumdar: This is actually a regional trend. However, while Nepal earlier stood as the country where independent media and civil society not accepted by their own countries could function fearlessly, the closing down of this space in Nepal is a great loss. As a journalist I myself was supported by the existence of the Himal Southasian platform. When the media of my home country, India, were not interested in publishing independent reporting from Afghanistan, Himal reached out to me and published my article for the eight years that I was based in Kabul as a freelancer. We are constantly approached by journalists wishing to write the articles that they cannot publish in their own national media.

The fact that regulatory means to silence media and civil society is meeting with such success here and that an independent platform is getting scarce support within Nepal’s civil society will also be a signal for others in power wishing to use the same means against voices of dissent.

It is a struggle for the media to be independent and survive. In an era where corporate interests increasingly drive the media’s agenda, it is important for all of us to reflect on what we can all do to ensure the survival of small independent organisations, many of which, like us, face severe challenges.

29 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

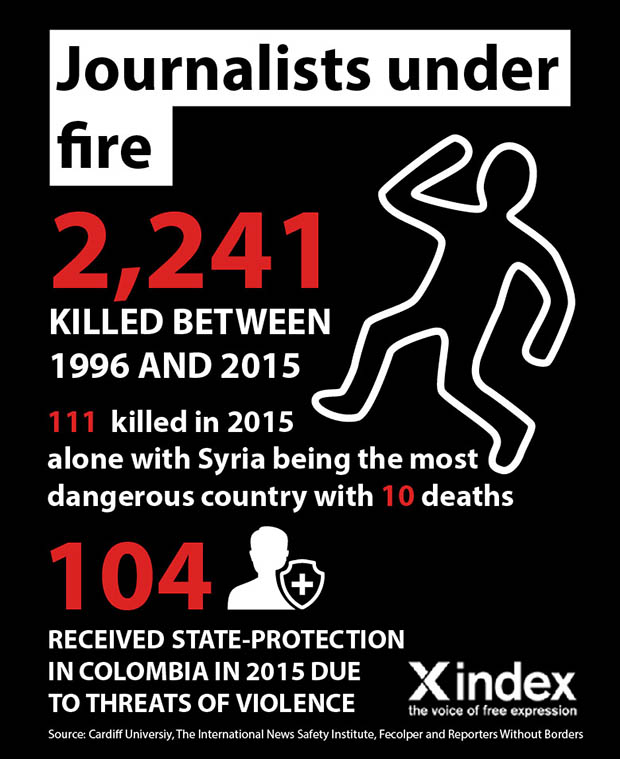

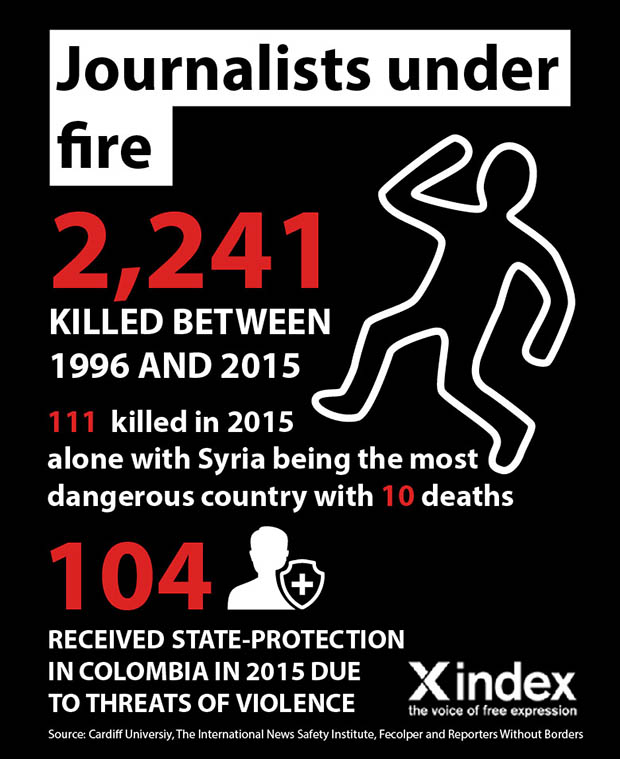

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index on Censorship has dedicated its milestone 250th issue to exploring the increasing threats to reporters worldwide. Its special report, Truth in Danger, Danger in Truth: Journalists Under Fire and Under Pressure, is out now.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Highlights include Lindsey Hilsum, writing about her friend and colleague, the murdered war reporter Marie Colvin, and asking whether journalists should still be covering war zones. Stephen Grey looks at the difficulties of protecting sources in an era of mass surveillance. Valeria Costa-Kostritsky shows how Europe’s journalists are being silenced by accusations that their work threatens national security.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76283″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Kaya Genç interviews Turkey’s threatened investigative journalists, and Steven Borowiec lifts the lid on the cosy relationships inside Japan’s press clubs. Plus, the inside track on what it is really like to be a local reporter in Syria and Eritrea. Also in this issue: the late Swedish crime writer Henning Mankell explores colonialism in Africa in an exclusive play extract; Jemimah Steinfeld interviews China’s most famous political cartoonist; Irene Caselli writes about the controversies and censorship of Latin America’s soap operas; and Norwegian musician Moddi tells how hate mail sparked an album of music that had been silenced.

The 250th cover is by Ben Jennings. Plus there are cartoons and illustrations by Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Sam Darlow and Chinese cartoonist Rebel Pepper.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. It has produced 250 issues, with contributors including Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: DANGER IN TRUTH, TRUTH IN DANGER” css=”.vc_custom_1483444455583{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Journalists under fire and under pressure

Editorial: Risky business – Rachael Jolley on why journalists around the world face increasing threats

Behind the lines – Lindsey Hilsum asks if reporters should still be heading into war zones

We are journalists, not terrorists – Valeria Costa-Kostritsky looks at how reporters around Europe are being silenced by accusations that their work threatens national security

Code of silence – Cristina Marconi shows how Italy’s press treads carefully between threats from the mafia and defamation laws from fascist times

Facing the front line – Laura Silvia Battaglia gives the inside track on safety training for Iraqi journalists

Giving up on the graft and the grind – Jean-Paul Marthoz says journalists are failing to cover difficult stories

Risking reputations – Fred Searle on how young UK writers fear “churnalism” will cost their jobs

Inside Syria’s war – Hazza Al-Adnan shows the extreme dangers faced by local reporters

Living in fear for reporting on terror – Ismail Einashe interviews a Kenyan journalist who has gone into hiding

The life of a state journalist in Eritrea – Abraham T. Zere on what it’s really like to work at a highly censored government newspaper

Smothering South African reporting – Carien Du Plessis asks if racism accusations and Twitter mobs are being used to stop truthful coverage at election time

Writing with a bodyguard – Catalina Lobo-Guerrero explores Colombia’s state protection unit, which has supported journalists in danger for 16 years

Taliban warning ramps up risk to Kabul’s reporters – Caroline Lees recalls safer days working in Afghanistan and looks at journalists’ challenges today

Writers of wrongs – Steven Borowiec lifts the lid on cosy relationships inside Japan’s press clubs

The Arab Spring snaps back – Rohan Jayasekera assesses the state of the media after the revolution

Shooting the messengers – Duncan Tucker reports on the women investigating sex-trafficking in Mexico

Is your secret safe with me? – Stephen Grey looks at the difficulties of protecting sources in an age of mass surveillance

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson depicts a fat-cat politician quashing questions

Scoops and troops – Kaya Genç interviews Turkey’s struggling investigative reporters

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Rebel with a cause – Jemimah Steinfeld speaks to China’s most famous political cartoonist

Soap operas get whitewashed – Irene Caselli offers the lowdown on censorship and controversy in Latin America’s telenovelas

Are ad-blockers killing the media? – Speigel Online’s Matthias Streitz in a head-to-head debate with Privacy International’s Richard Tynan

Publishing protest, secrets and stories – Louis Blom-Cooper looks back on 250 issues of Index on Censorship magazine

Songs that sting – Norwegian musician Moddi explains how hate mail inspired his album of censored music

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

A world away from Wallander – An exclusive extract of a play by late Swedish crime writer Henning Mankell

“I’m not prepared to give up my words” – Norman Manea introduces Matei Visniec, a surreal Romanian play where rats rule and humans are forced to relinquish language

Posting into the future – An extract from Oleh Shynkarenko’s futuristic new novel, inspired by Facebook updates during Ukraine’s Maidan Square protests

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world: Josie Timms recaps the What A Liberty! youth project

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The lost art of letters – Vicky Baker looks at the power of written correspondence and asks if email can ever be the same

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines,

One of South Asia’s most influential news magazines,